This adaption from The Visionary State appeared in the May 2005 edition of the cool freak rag Arthur.

Druid Heights

I first heard about Druid Heights a few years ago, when I began doing research for a book about the history of alternative spirituality in my home state of California. A musician, Colin Farish, described about a gorgeously constructed round wooden building hidden in the woods of Marin County that once served as a library for Alan Watts. Farish told me that the building was condemned, and that he was working hard to save it, perhaps by transporting it elsewhere. It turned out that Farish had lived on the property where the library stood, a hidden bohemian community that went by the intriguing name of Druid Heights.

The Heights was and is one of those rare places that is known but not known. It was the site of hundreds of amazing parties over the last fifty years and yet remained tucked beneath some freaky beatnik cone of silence, its muddy dirt road still unmarked on many maps. I became, as they say, fascinated, and began to dip into the history of this extraordinary place, whose highs and lows could fill a multi-volume tragi-comic saga, a countercultural Peyton Place.

The story of Druid Heights begins when the longtime lover of the New York poet Elsa Gidlow died on the eve of World War II. Devestated, Gidlow decided to abandon her bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village and hitchhike to California. This was an unusual thing for a woman to do in 1940, but Gidlow was an unusual woman. Fiercely independent and largely self-educated, Gidlow had been raised in poverty before moving to New York to edit a poetry journal as a young woman. She was both an anarchist and a lesbian, and in 1923, published On a Grey Thread, the first unabashedly sapphic book of poetry issued in the United States. She could handle hitching across the states.

Arriving in Marin County, Gidlow holed up in a derelict house in rural Fairfax. She was forty years old. Facing winter solstice alone and unsettled, she decided to perform what she later described as a “transforming ritual.” As a storm raged outside the leaky house, she built up a roaring blaze of madrone logs. Slowly, Gidlow sensed the room fill with the spirits of all the mothers and grandmothers who have ever tended fire, all the way back to the Paleolithic. “I knew myself linked by chains of fire,” she wrote, “to every woman who has kept a hearth.” In the morning, Gidlow honored this rather neo-pagan vision by wrapping some of the cold coals in foil and red ribbon, and keeping them for next year’s solstice fire.

In 1954, Gidlow brought one of these solstice charcoals to her new home, a junky five-acre patch of rural hillside on the edge of Muir Woods, lying at the end of a precarious road more clay than dirt. Shadowed by a looming wall of eucalyptus to the southwest, a few tumble-down frame houses and barns were already returning to earth, and there was no plumbing to speak of. Gidlow dubbed the place Druid Heights, and it would soon blaze into a hidden hearth of bohemian culture, a “beatnik” enclave years before the term was born or needed, and later a party spot for famous freaks. Scores of sculptors, sex rebels, stars and seekers lived or visited the spot over the decades, including Gary Snyder, Dizzy Gillespie, John Handy, Alan Watts, Neil Young, Tom Robbins, Catherine McKinnon and the colorful prostitute activist Margo St. James. Too anarchic and happenstance to count as a commune, Druid Heights became what Gidlow jokingly called “an unintentional community:” a vortex of social and artistic energy that bloomed out of nowhere, did its wild and sometimes destructive thing, and, for the most part, moved on.

Gidlow initially shared the property with a man named Roger Somers and his wife Mary, the couple who had actually found the place. A visionary house builder and jazz musician, Somers moved to Marin in 1950 and was one of the more breathtaking bon vivants of that or any era. In his woodwork and design, Somers developed a flamboyant, organic, deeply Californian style influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright, Japanese architecture, and the twists and turns of living things. (He once met Wright by impersonating a busboy at a Florida hotel and bringing the master and his hot wife their breakfast.) Somers’ most outlandish commission was a tour bus he built for Neil Young in the mid-1970s, a massive elven dream machine festooned with teak siding, a roof-deck, and syrupy Art Nouveau appliqué. Young took it out on the road only a couple times; rumor has it that the bus now houses chickens on his Broken Arrow ranch.

The odd stanchion from Young’s bus can still be found tucked away in some of Druid Heights’ homes and structures, most of which were built or converted by Somers and a man named Ed Stiles. A custom furniture maker from the East coast, Stiles first tracked down Somers in the early 1960s after seeing a photograph of him and a bare-breasted Mary in an sensationalist article on the California scene in Esquire. Somers invited the young artist to live at Druid Heights and install his shop in a building there in exchange for giving Somers access to his woodworking tools. For his commercial work, Stiles favored South American hardwood, and built furniture for churches and local figures like Graham Nash. (A music stand he built in 1968 was included in a Bay Area design show at SFMOMA.) But like Somers, Stiles also enjoyed working with salvaged materials; for his homes and workshops, he let the lumber before him organically guide his hand rather than following plans or building codes.

One time Stiles used a redwood industrial process tank and a modified flash boiler to construct a hot tub, now a crenellated ruin crumbling into the hillside behind his home. He opened it up to everyone at Druid Heights, and one day he came by to discover a nubile Judy Collins soaking away. “I thought of it as a good thing,” he says with a smile. Another visitor was a local dentist who commissioned Stiles to build an improved model in his backyard, which is how the first full-time, filtered, self-regulating Marin County redwood hot tub was born. Stiles built about thirty tubs over the years, but when demand sky-rocketed after a 1971 Sunset magazine article appeared, he chose to retire. “I wasn’t interested in it as a business. I thought tubbing was an important social phenomenon. When people get naked together, they no longer carry the pretensions of their careers or identities. It was a great equalizer.”

Throughout the late 1960s, Stiles thought he had died and gone to heaven, having found a creative and visionary community that sustained itself far from the workaday world. But things grew darker in the 1970s. A family guy who was never into drugs, Stiles was increasingly bummed out by many of the colony’s revolving cast of characters. One resident, who engineered the device that injected LSD into the gelatin squares of Clearlight acid, was surrounded by a loose circle of cronies that included a particularly paranoid Viet Nam veteran. At one point this fellow took to hunkering down in the hills at night, armed to the teeth and scanning for narcs and little green men from Mars. “I enjoy weirdness,” Stiles says. “People stoned on acid jumping up and down on cars naked? I didn’t mind that. Guys with semi-automatic weapons, false IDs, and tons of ammunition? That I minded.” Angry and depressed, Stiles almost left the community. Then Somers himself got ripped off. His money, his cherished reed instruments, and the stash he kept in a World War II ammunition box was gone. “After that he shut down the bullshit.”

Another complicating factor during the 1970s was the U.S. Forest Service, which upset Druid Height’s natural social balance i.e., shared bohemian poverty by making deals with the various owners in order to buy them out. “It functioned well until the Forest Service came around and there was money available,” Stiles says. “Then everybody started to fend for themselves.” Today Stiles and his wife are the only members of the old guard still holding down the fort. Stiles has a lifetime lease on the renovated commercial chicken barn he lives in, a funky weathered jewel of a home, but in the eyes of the Interior Department, the handful of other folks who still live at the Heights are borderline squatters. Few of the buildings are built to code, but it remains to be seen whether the Parks Service plans to tear them down or preserve them. Stiles isn’t sure what is worse: the destruction of Druid Heights, or what he fears will be “a beatnik Disneyland.” For the moment, the community shuffles on, a sober shadow of its former self.

Gidlow died at home in 1986, and her ashes were mixed with rice and buried under an apple tree. Somers lived there until 2001, when he passed away in his redwood hot tub, soaking alone just two days after 9/11. Stiles nurses complicated feelings about the man who so enriched his life but who also caused him a lot of grief. “He absorbed all the oxygen for a mile around him. And he was so charming he could get away with it.” Most of all, Stiles expresses admiration. “He was the only person I ever knew who just didn’t buy it. He never accepted the whole bullshit society thing. He rejected what you were supposed to do, whether it was about sex or food or architecture. He was beyond a rebel. He just made up his own rules as he went. He didn’t lie, he just followed his own rules.”

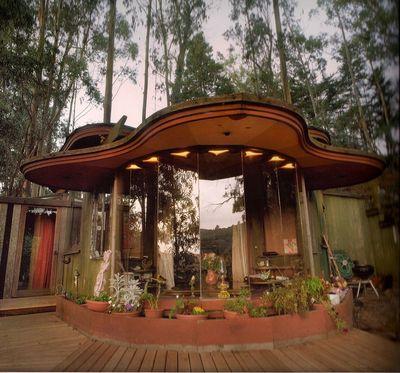

You can sense Somers’ sprit in much of the architecture of Druid Heights, especially an exuberant round home known as the Mandala. Stiles built the bare bones of the place for Gidlow’s sister, and it was heavily modified by Somers after Alan Watts commandeered the place. Despite its mystic name, the blobular, radial structure looks a bit like a clown from the hillside behind it, a resemblance that Somers claimed was intentional. “Most people live in a box,” he would say. “I live in a clown’s head.” Somers tricked out the interior with ingeniously embedded lights, dragon glass, skylights, and a dining table sunk into the plush carpet floor for maximum comfiness. Outside the wall-like front windows lies a redwood deck where San Francisco’s notorious Mitchell Brothers once shot a porno starring the foxy Annette Haven.

Sexual experiment was only one of the colony’s means of exploring the boundaries of consciousness. One of the most charming structures on the land is a simple meditation shack that juts out from the hillside. The irregular clapboard shingles resemble seismic graphs, while the mitered windows pop out like quartz crystals or eyes agog with vision. The snug interior features Japanese wall-paper and a ceiling covered with bamboo slats, and it almost demands quiet contemplation. The shack was built by men long gone, but its Pacific Rim twist was first established at Druid Heights by Somers, who built an amazing shoji room inside the farmhouse that served as his first home on the property. A raised platform surrounded by paneled screens that Somers made out of cheap fiber-glass material rather than rice paper, the graceful and inviting zendo-like space once featured a buddha and kamidana, or ancestral shrine. During the summer, sunlight pierces a large telescoping round window to the north, which is crossed by two thin wooden shelves that resemble wispy clouds. Here Alan Watts gave lectures on Zen aesthetics; here Tom Robbins cavorted with groupies for all to see.

If there was a spiritual force behind the hedonism of Druid Heights it came from the East, from the sly immediacy of Zen and the earthy anarchism of the Tao. Already in the mid-1950s, Gidlow was studying Chinese and calligraphy at San Francisco’s American Academy of Asian Studies, a groundbreaking center of East-West exchange and a seedbed for the hybrid hippie forms of Zen, Taoism, and Hindu Vedanta to come. In the 1960s, the Beat poet and Zen practitioner Gary Snyder lived at the Heights with his Japanese wife Masa, while barefoot monks from the San Francisco Zen Center’s nearby Green Gulch farms would occasionally tramp over for a visit. Stiles, who had no interest in religion or Japanese architecture, was nonetheless responsible for carving a rosewood staff for Shunryu Suzuki, the legendary roshi of the Zen Center. Even the land itself seemed unrolled from some Chinese scroll, with its gnarled cypresses and a craggy rock in the distance dubbed “Cloud Hidden.”

The rock got its name from Watts, the most illustrious spiritual hedonist associated with Druid Heights. An ordained Episcopalian priest, Watts moved to the Bay Area in 1951 to teach at the AAAS, where he may have met Gidlow. With his seminars, KPFA radio shows, and books, beginning with 1957’s The Way of Zen, Watts coaxed countless hip and literate Americans into the deep stream of East Asian art and mysticism. Emphasizing perception and spontaneity rather than formal practice, Watts painted a picture of the Tao that was fresh, resonant, and countercultural avant la lettre. By experiencing the Way or the “suchness” of things, Watts claimed, we can temporarily shed our “skin-encapsulated ego.” This expansion of consciousness reveals the larger ecological reality of which we are always already a part. Such insights also deconstruct the social programming we take to be our personalities.

Today Watts’ writings and recorded talks still shimmer with an visionary lucidity. But though Watts took the Beatniks to task for their druggy, rebel Zen, he himself did not exactly behave like the sober spiritual master many took him for. A notorious womanizer and hardcore alcoholic, Watts embodied the full contradictions of the countercultural seeker, a boundless and excessive spirit who sailed beyond the boundaries of conventional morality. Though he wrote frankly about the need to balance mysticism and sensuality to be “both angel and animal with equal devotion” his hymns to spontaneity can sometimes seem like justifications for license and his own lax engagement with formal spiritual practice. When Stiles met him, the Brit was deeply in his cups, spouting obscene limericks. “I liked him immediately.” But Stiles was also astonished at the amount of alcohol Watts consumed. “I asked myself how can anyone consume a fifth of vodka every day and live.” When the middle-aged Watts died in the Mandala in 1973, Stiles had his answer: you can’t.

Druid Heights was the place Watts went to unwind, his spiritual home turf. You can sense the jaw-dropping beauty of the place in his classic The Way of Zen, when he describes the essential aimlessness of the Tao as a kind of natural freedom:

the freedom of clouds and mountain streams, wandering nowhere, of flowers in impenetrable canyons, beautiful for no one to see, and of the ocean surf forever washing the sand, to no end.

Watts dedicated his autobiography to Gidlow and 1962’s The Joyous Cosmology to the people of Druid Heights. The latter book, a slim volume subtitled “Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness,” was Watts’ Doors of Perception: a limpid and profound description of a group of friends including “Ella” and “Robert” all exploring the “goal-less play” of LSD. The same year, Watts holed up with Somers and some other hep cats and recorded an astounding tribal freak-out LP called This Is IT, which includes Somers and Watts performing spontaneous voodoo scat over bongos.

In the early 1970s, Watts decided he wanted his own library at Druid Heights, but when Stiles saw the austere and expensive Japanese box Watts wanted to build, he convinced him to try out a round structure instead. Somers drew up the blueprints, adding his characteristic panache, and a young man living onsite built it for a fraction of the estimate on Watt’s original library plans.

Looking like a large redwood hot tub crowned by a sylvan UFO, the snug little pad sits on a redwood platform regularly pelted with sticky eucalyptus droppings. Sinewy posts on an interior balustrade show Somers’ continued devotion to the tao of wood; Somers also used thin 2x3s for the side-nailed redwood deck. These did not just bring elegance; Somers also knew that, since the lumber shops had to split 2x6s to fill the order, you got less knotty, higher-quality wood without extra cost. After Watts died, some of his ashes were scattered outside, where a single weathered marker, crafted by Stiles, is sunk in the clay. Gidlow then dubbed the space the Moon Temple, and made it available to some of the lesbian writers who started flocking to Druid Heights in the 1970s, during the golden age of goddess feminism.

Though Watts spent a good time living and partying at Druid Heights, his main Marin center of operations lay elsewhere. The S.S. Vallejo began life as a steam-powered paddle-wheel ferry, shuttling passengers between Vallejo and Mare Island before the Bay Area’s bridges snuffed out the colorful era of ferry travel. After completing her final run in 1948, the Vallejo was abandoned in a Sausalito shipyard built by the Bechtel Corporation during World War II. There an exuberant Greek artist named Jean Varda found the vessel and purchased it with some fellow artists. The Vallejo became the nucleus of Sausalito’s hard-scrabble houseboat hipster scene, which attracted scores of beats and bohos to the mud-flats north of town, where folks had been vacationing in their “arks” since the 1880s. Kerouac himself stayed on the boat, supposedly building a fence around the landing during one of his notorious alcoholic tears. Well into the 1990s, the Vallejo continued to house outlandish characters and host outrageous parties, and its current owner is an old friend of Timothy Leary’s who played a major role in the glory days of virtual reality. A fabulous Lovecraftian account of the boat’s recent renovation was written the strange visionary artist Steven Speer, who sometimes makes his home there.

While he lived, Varda was the soul of the Vallejo. When he wasn’t sailing, cooking, or enjoying the company of beautiful young women, he made colorful cubist collages and mosaics out of textiles, wood, and other found materials. Varda’s embrace of collage a frugal art of scavenging and juxtaposition that compelled many postwar California artists also remade the Vallejo. Varda painted its flanks with suns and pennants, hung colored bottles in the windows, and embedded shards of glass around the fireplace to catch the light.

In 1961, Watts and his wife Jano moved onto the Vallejo, taking over all but Varda’s portion of the boat. Under the auspices of the Society for Comparative Philosophy, which also helped him hide his money from his ex-wives, Watts held Zen teachings and seminars in the loft-like space, including a combative 1967 gathering with Tim Leary, Gary Snyder, and Allen Ginsberg published in the Haight Street hippie rag The Oracle. At the time, much was made about the difference between Varda’s outrageous decor and Watts’s austere Zen interior, with its white walls, dark wood, and large bronze Buddha. But eventually the two men sawed a doorway between their two sides to facilitate the flow.

For me, this doorway also opens into one of the great themes of California’s bohemian spirituality: the endless interplay between sense and spirit, artful partying and higher consciousness. From the outside, this hedonistic spirituality can look like sloppy indulgence, or a deluded attempt to have your cake and eat it too. For all the profundity and wisdom of Alan Watts, one cannot help but wince at the paradoxes of his life and his lecherous alcoholic decline. For today’s conservatives, who love to attack the permissive mores of the counterculture, such behavior is all the proof you need that going with the flow is a pact with the devil. Terrible and venal hypocracies emerge from such law-abiding fears, of course, as well as a raft of resentiment, but that’s another story. The important question here is about gambling on spontaneous grace, and the courage involved in commiting to energies outside the comforts of conformity, even when things may go awry as they inevitably do. The anarchy that eventually undermined Druid Heights as a community also allowed its spontaneous creativity to bloom, a creativity that left its mark on some buildings and a handful of cultural artifacts, but whose incandescent play mostly passed away in the very moment of its blaze. That very fleetness, it seems to me, is the abiding teaching of this place, and tof he spiritual hedonists who lived there.

“Everything kept goes stale,” Watts once said. Though Roger Somers left much of himself in his strange, amazing structures, he never considered their possible preservation. He just assumed, and perhaps even hoped, that his fluid forms would simply crumble away, merging into the stream of things just as the eucalyptus fades into fog.