Cosmic choral chaos

I’m not sure if it’s all the time I used to spend in zendos, but when I find myself in a modern American symphony hall, I usually treat these highly coded and uptight environments as an invitation to focused attention. Once everybody shuts up and the music starts, I sit as still as possible, sans the usual pint, and devote myself to listening, with mind and heart in as much sync as I can muster. This attitude, which can often be as worthwhile as the music itself, really comes in handy when the pieces performed are not the usual warhorses, but the sort of “challenging” and unfamiliar modern and contemporary works I can appreciate in recordings but often find tough to engage while I am writing or puttering around the house.

And so it was that I settled with rapt passivity into my orchestra seat for the San Francisco Symphony’s first performance of Ligeti’s monstrous 1965 Requiem earlier this year. After a tasty baroque bonbon conducted by the Symphony Chorus director Ragnar Bohlin, Michael Tilson Thomas took the tiller, offered a few words of gentle warning, quoted Rilke, and dove into twenty-five minutes of supreme apocalyptic weirdness.

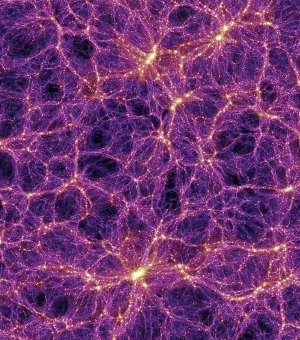

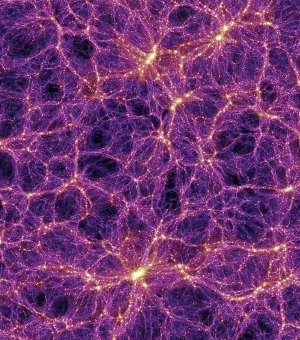

Said to be partly inspired by the composer’s own reactions to the Holocaust, during which his entire family save his mother was killed, Ligeti’s Day of Wrath melts historical horror into an underworld of universal and sometimes impish dread. The ominous drift of the opening Introidus, with some Gyoto monk-worthy growling from the basses, soon splintered like some shuddering ice crystal planet into the mountainous chromatic clouds of the Kyrie. Twisted into skeins of galactic dust, the massed human voices became a fractal dance of dissolution and dynamic crystallization, the perpetual solve et coagula of Ligeti’s justly celebrated micropolyphony. The fluctuating lines and hair-splitting intervals that make up the music’s twenty separate contrapuntal parts transformed the hall with an organic underworld of half congealed aethyrs, so tricksy and difficult for the chorus to pull off that a number of singers sported tuning forks.

I am not the most intellectual or analytic listener. Whenever the opportunity affords itself, I go for transport. Give me a keening emotion, an exotic evocation, an entrancing drone, a psychedelic arabesque, and I am outta here. Within minutes, the disturbing immensity of Ligeti’s sound world lifted me out of my seat. As the usual Cartesian coordinates of melody, harmony, and pitch became lost in a chromatic atmosphere at once iridescent and opaque, all familiar reference points—the concert hall, the singers, the city beyond—seemed to melt into the a claustrophobic and towering soundscape against the frightening backdrop of Pascal’s infinite spaces. Even the hair on the back of my neck came to attention, and I submitted to an ominous undertow of awe.

Somewhere during the Kyrie this transport became epiphany, a far rarer occurence in my lexicon of listening. Instead of acting as a drug or a dreamlike trance, the Requiem became a mirror of the act of listening itself. Music melted into sound, sound into an almost tactile polyverse of now now now. The hall became a stage where the self that witnesses the waveforms of musical material realizes its own identity as a wave of vibration. My whole body became an ear, jolts of energy tickled my spine, and the rhetoric of apocalypse—which means, of course, revelation—bloomed into a stark and impersonal unveiling of music as such—not the 20th century abstraction of “absolute music,” but the luminous roar of organized sound as a fundamental dimension of reality and meaning. This got me so tripped out that, when the hotshot Argentine pianist Martha Argerich took on Ravel’s G-Major Piano Concerto after the intermission, I could barely relate. The piece was sparkling, her playing was rich with confidence and wit, and the crowd was in love, far more than they had been with Ligeti. But the music sounded to me like a Wurlitzer organ cranking away in a carnival while the aftershocks of some stellar catastrophe faded in the far atmosphere.

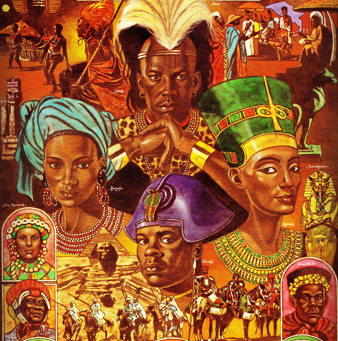

Reflecting on this experience later, I realized that my epiphany could be boiled down to the simple Pavolovian fact that, like millions of earthlings, I first encountered Ligeti’s eerie choral micropolyphony in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. A passage of his Kyrie is associated with the inky black monolith whose appearance heralds and may actually trigger breakthroughs in human consciousness. Coupled with Kubrick’s images of chilly sublimity, Ligeti’s sounds become another sort of extraterrestrial artifact, a literally otherworldly chorus composed equally of angels and aliens. Ligeti, of course, did not especially care for this exposure, and he also spent six years trying to pry some compensation out of MGM for their unauthorized use of his music. Nonetheless, Kubrick’s appropriation can only be seen as a kindness of mutual infection. The film not only exposed millions of people to real-deal experimental music—in effect squeezing pop exoticism out of a product of the intellectual elite—but also trained the minds of movie goers like me to map the more obvious imaginative transports of visual media onto the incorporeal vectors of intensely novel music.

A pop fusion of “cosmic” sounds and images all too often becomes a kind of kitsch, from New Age poofery to space-age bachelor pad soundtracks to the comic-book pulp of 70s prog. (Not to say I don’t dig kosmiche kitsch.) But this cartoon excess should not obscure the subtler ways that Ligeti’s Requiem engages the extraterrestrial imagination, and that can account, beyond the monolith association, for its enormous evocative power.

Ligeti himself often used spatial metaphors to describe his work, as if we are forced to imagine a kind of parallel world capable of housing such music. We are impelled by imaginative necessity to speak of masses, crystals, tapestries, fractals. Discussing the way his rigorous contrapuntal structure is submerged inaudibly in his music, Ligeti himself spoke of the “very densely woven cobweb” of his choral writing. In the manner of the imagination, this image triggers another: a childhood dream in which Ligeti finds himself entangled in a giant web, along with various insects and decaying pieces of junk. In the dream, he became a captive witness to the gradual transformation of what Philip K. Dick would recognize as the “tomb world,” as the insects struggled to free themselves from the perpetually shifting web, like human voices that wake us as we drown.