Toys and Idols

A tale of two action figures: in “The Sacred Arts of Vodou,” a traveling exhibit that made the rounds in 1998, UCLA’s Fowler Museum of Cultural History cobbled together an impressive range of costumes, ritual objects, paintings, flags, and videos in order to get across some of the power of Haiti’s rich and popular religious tradition, whose gods bristle with all the foibles and lusts of Zeus’ ancient crew. But unlike the Olympians, the Haitian pantheon is a living tradition, and Vodou practitioners use whatever cultural materials lie at hand in order to ground their cosmology in everyday life cheap lithographs of Catholic saints, for example, were widely used as syncretic masks for decidedly “pagan” deities. The Fowler exhibit closed with three installations, based on documentary photos of Port-au-Prince altars and touched up by a Vodou priest. The first two arrays of doll-like figures and sacred bric-a-brac were devoted to Haiti’s two main groups of gods, the Rada and the Petro. But the final altar, bathed in black and purple, gave viewers a peek into a far more creepy and esoteric world: the secret society Bizango, a kind of mafioso that traffics in black magic and Masonic ritual. And there, among the skulls and candles, the coffins and chains and phallic canes, stood a foot-high figure of Darth Vader.

Unless you keep your nose well above the intoxicating swamp gas of pop culture, you probably know that before Vader succumbed to the dark side, he was the student of the Jedi muppet Yoda. An inch-high plastic knock-off of Yoda, clutching a cane and sadly lacking the snake prized by eBay collectors, is glued to the dashboard of my Subaru Outback. Though I generally keep my sci-fi geekdom corralled inside the confines of Star Trek, Yoda first hit my budding consciousness about the time I discovered the I Ching, “Kung Fu” re-runs, and pot. He was a kind of gateway drug, a cartoon toke of the Zen koans and Taoist lore I would imbibe in later years. In fact, scuttlebutt around the Zen Center of Los Angeles has it that Yoda was based loosely on Taizan Maezumi Roshi, the diminutive, crinkly-eyed, and staff-clutching Japanese Soto priest who helped bring the dharma to the heart of Tinseltown.

Whether the story is apocryphal or not is beside the point, because both these action figures speak to the tremendous archetypal punch that the original Star Wars series landed in the collective gut. And yes, we are still reeling from the blow. Even as Lucasfilm’s imperial hypetroopers assault our crowded little world with The Phantom Menace, the fallout from Star Wars keeps coming down. Lucas made a new kind of movie, one which dominated hearts and minds without having, say, a good script, real characters, decent acting, or thoughtful editing. All that didn’t matter, because Star Wars worked its undeniable magic on the level of images. A kind of postmodern classicist, Lucas took cues and costume tips from Nazis, the Western, Kurosawa’s samurais, Taoist sages, Flash Gordon, Arthurian legend, Greek myth, and The Wizard of Oz. He constructed a fantasy world that, like Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, was deeply personal in its obsessive detail but profoundly impersonal in its archetypal wiring. But Lucas’ special genius was to use his eye candy never-never land to stage a classic heroic narrative, one whose appeal, like the cartoon passions revealed on medieval stained-glass windows, was actually enhanced by reducing its viewers to awestruck puppies.

For some, this made Star Wars an object of cult veneration; for others, a kind of infantile black hole, consuming whatever intelligence and wit orbited the outskirts of Hollywood. As Clarke

Cooper pointed out in a recent issue of Hermenaut, this debate over whether Star Wars is a monument of American cinema or “the stuff false consciousness are made of” is an ultimately religious matter. That is, it depends, like religion, not on the ephemeral fluctuations of taste or opinion, but on a far more basic framework that defines how you see the world in this case, how you perceive the possibility of truth in movies. For Cooper, an arch “Star Wars revulsionist,” movies that rely on effects to entertain their audiences are as empty and incomprehensible as the Eucharist is to an atheist. They have no semantic content; they are not really movies at all, but “side effects of a large-scale fleecing project.”

Cooper helps explain the ashen taste that lingers on the palette following exposure to films like Armageddon and Jurassic Park, but I am afraid that modernists like him will never understand Star Wars, because its semantic content is not really modern at all. Lucas did use film as a medium for truth, but it was mythopoetic truth, which to contemporary eyes often appears as a fusion and confusion of cliché and archetype. Using Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces as a user’s manual, George Lucas constructed the story of Luke Skywalker out of the bits and pieces of traditional tales: the holy fool, the wise hermit, the father’s sword, the lost princess, the sacred grove, the labyrinth, the beast. But though Lucas’ princess was sassy and his blades were neon, the man did not really challenge or subvert these archetypal building blocks, not because he was lazy or particularly reactionary, but because he did not believe, pace modernism, that we would be free when we left such enchantments behind.

***

When Star Wars hit the screens in 1977, America was not exactly a glowing advertisement for the joys of disenchantment. Wracked by Watergate, Vietnam, the energy crisis, recession, and the slow, tubercular decline of a once utopian counterculture, the 1970s sank into a toxic anomie that perhaps could only be dispelled by the brash trumpets of an audacious fairy tale. (Of course, these very same qualities helped make the early 1970s the greatest era of American film, a time of formal experiment and existential depth that Star Wars helped to snuff.) Star Wars offered spectacular redemption, a restoration of good will and a glimmer, perhaps, of the Reaganite myth to come. It also came with a new kind of merchandising plan. Like medieval relics, Star Wars junk was an integrated aspect of the event itself, a trace of the real deal. Lucas did not just tap the collective unconscious; he discovered the collectable unconscious.

But carping about the corporate colonization of the imagination only gets you so far, especially since Lucasfilms is really a corporation of one. When the economy can’t tell the difference between values and commodities, how can we expect our cultural workers to clearly divide meaning and merchandise? Star Wars sold a lot of t-shirts, but it also gave millions of kids an uncomplicated image of the Good, and I think you have to be a pretty ornery cuss to write off that sort of mass “religion” as nothing but false consciousness. Snort if you want to, but the Force provided a popular image of cosmic purpose that, in its pantheistic impersonality, could survive the cold vacuum left by the death of God (that’s why the Fundies were so upset at the time). And though many gagged on the movie’s trite language of good and evil, Luke’s unfolding relationship to Darth Vader actually complicated this simple dualism, providing a primal tale of fathers and sons in an era that had a tough time grappling with either.

Star Wars also mythologized our deepening relationship with technology, providing a contrast between the necromantic systems of the Empire and the organic gadgetry and friendly droids of the Rebel Alliance. But Lucas’ fantasy was technological on a formal level as well. The unprecedented success of Star Wars depended largely on effects, not just special effects but on the whole rhetoric of film as an event, a programmed experience rather than an investigation of human meaning. Directing his actors like they were mannequins, Lucas saved his energy for kinetic edits, detailed models, visual dazzle, and roller-coaster POVs. Critical distance was swamped by Lucas’s restless visual energy and John Williams’ overwhelming German Romantic soundtrack. Star Wars was a dime-store Ring, Wagner’s “total work of art” for an artless age of technological consumption. Perhaps Lucas’ real patron saint is not Campbell but Marshall McLuhan, who argued that electronic technology was dissolving literate self-consciousness and immersing us in a world of near-magical thinking.

With its unrivalled deployment of “technological wizardry,” Star Wars opened our eyes in a new way, and Lucas was able to take advantage of that soft, exposed perceptual space to lay the foundations of his old-school fantasy world. In other words, by lacing the mead with high-tech opium, Lucas could really become a bard, and it’s up to you to judge if the tale was worth the telling. But the novelty that Lucas exploited came with a curse, because the most potent media technology is destined to grow stale in time. Much of Star Wars looks like grainy cardboard these days, far more corny than, say, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and rather flaccid compared to the Streetfighter leaps and time slips of The Matrix. Presumably it was the fear induced by the specter of technological obsolescence that impelled Lucas to tinker with his films when he re-released them a few years ago, and the results were anxious and rather sad. In this sense, there will never be another Star Wars, at least until we get smellovision or fully-immersive “feelies” that Huxley prophesied in Brave New World. The perceptual space of media is now too dense and crowded for Lucas’ primary colors.

***

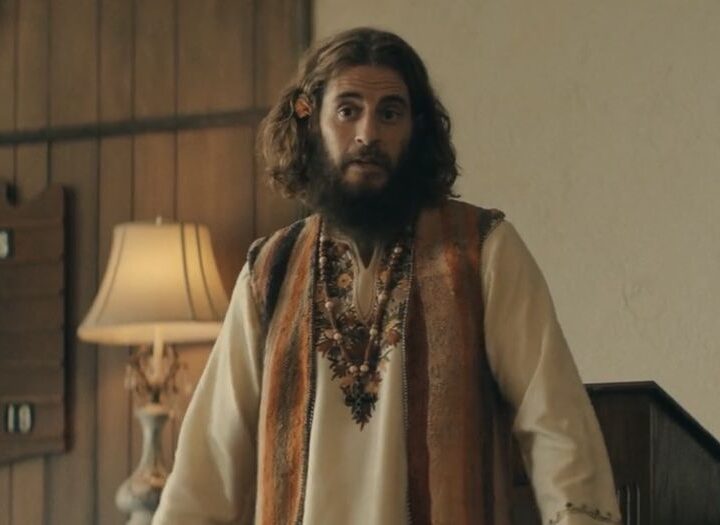

Which is why The Phantom Menace will not, I suspect, strike the resonant chords its predecessors did, however long the fans genuflect in line and however much paraphernalia they buy. For one thing, what we need to dispel these days is not the smoggy gloom of the mid-1970s but the garish triumphalism of the new economy. As such, folks should be bored by movie myths that depend too much on special effects to build “objective” photo-realistic worlds, because it just looks like another con, another “virtual community” devoid of real people. The most envelope-pushing special effects now speak to our growing distrust of simulation, a distrust perhaps first announced by the morphing technology that transformed Terminator 2’s evil T-1000 android from a cop into a linoleum floor. The best effects in The Matrix do not construct virtual worlds but express the mutations of subjectivity of movement and especially of time that our heroes experience as they manipulate the constructed nature of the reality they already inhabit. Instead of Yoda’s “go with the flow” pop Taoism, we have Morpheus’ “reality is a trap” pop gnosticism. Redemption is possible, but only at the expense of our own illusions: the steak is really a manufactured dream of pleasure; the babe in the red dress is actually a Man in Black.

For folks who grew up on Star Wars, The Matrix provides mythopoetic science fiction that can stand up to the more anxious and skeptical demands of adulthood in the digital age. As my friend Byron Gato put it, “If Star Wars gave us the map, The Matrix gives us the directions.” The Wachowski brothers film was able to slip its potent notions past the Hollywood censors by latching them onto trench-coat ultraviolence and video-game mayhem. But in the wake of Littleton, the world may feel safer with The Phantom Menace, which from all signs looks to be a kid’s movie.

Star Wars always had a childish element, which came to fore in Return of the Jedi, whose wretchedly cute Ewoks the only creatures who have children in the original series impelled many an audience member to start rooting for the hapless stormtroopers. But now Lucas has focused much of his epic on an eight-year-old apprentice, a 14-year-old queen, and a goofy amphibian named Jar Jar Binks, whose race the Gungan were named after a word Lucas’ two-year-old used to describe heavy machinery. The Star Wars tables at Barnes & Noble are evenly split between “adult” fare like The Essential Guide to Droids and a smorgasbord of coloring books, big-print readers, punch-out books, and vaguely educational pap. Lucas is clearly betting that we must become children again to enter the mythic kingdom. It’s not necessarily a bad move, and not just because he’s getting in on the ground floor of a generation. Perhaps it really is the best time to program soft young minds with Yoda messages like “fear leads to anger; anger leads to hate; hate leads to suffering.” I’m still trying to get off that particular merry-go-round myself.

The thing is, the child at the heart of The Phantom Menace, bright young Anakin Skywalker, will flower by the end of the three-part series into Darth Vader, the evil emphysemic overlord of the future Empire. I don’t know what that narrative arc says about the fears we have about kids today, whose immersion in alien technologies, violent video games, and post-literate culture is already widening the generation gap into an intergalactic void. Maybe it doesn’t say anything at all. But I suspect that whatever mythic density The Phantom Menace can conjure from its quick cuts and astonishing computerscapes will be drawn from this coming darkness. All the villagers used to know how the good stories ended, but it is rare to walk into a popcorn movie knowing that things will turn out rather badly. Perhaps The Phantom Menace, and before that Titanic, point to some strange yearning for a return of Fate. Not because it makes events seem preordained happy resolutions already did that but because it makes them seem real.

This piece about Star Warsology originally appeared in Feed, in response to Episode 1.