My guest post to David Gill’s PKD blog

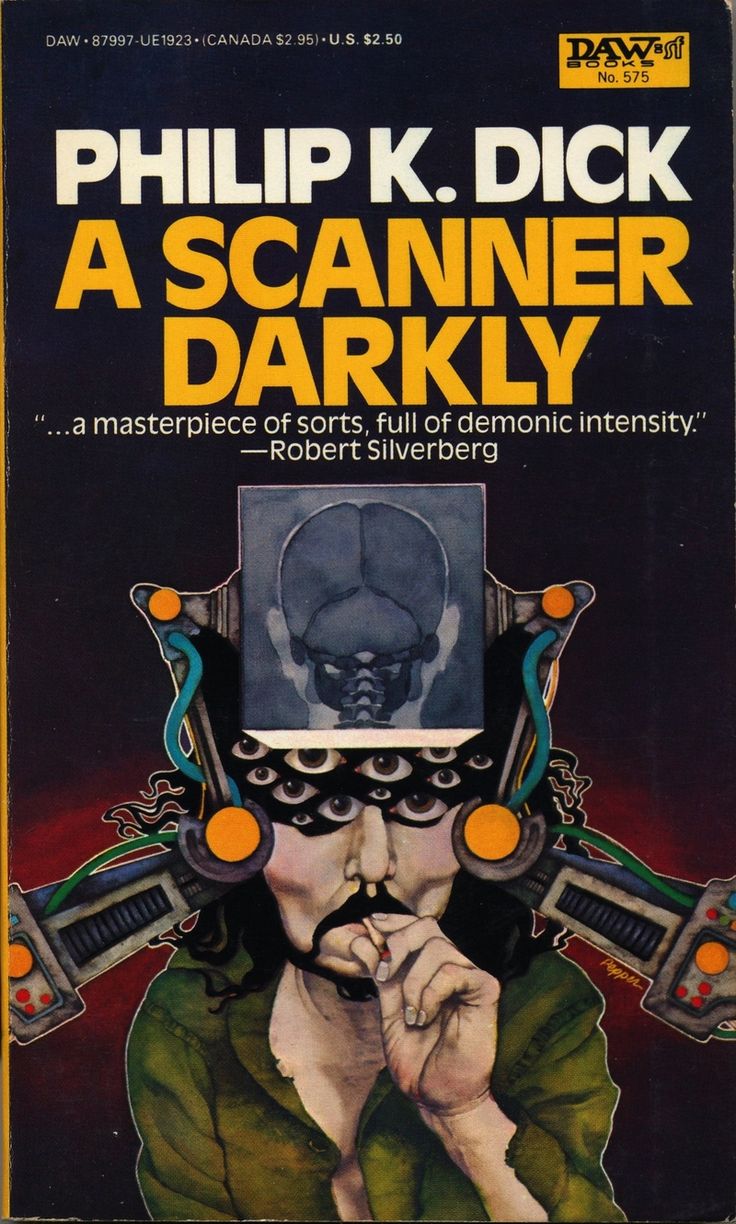

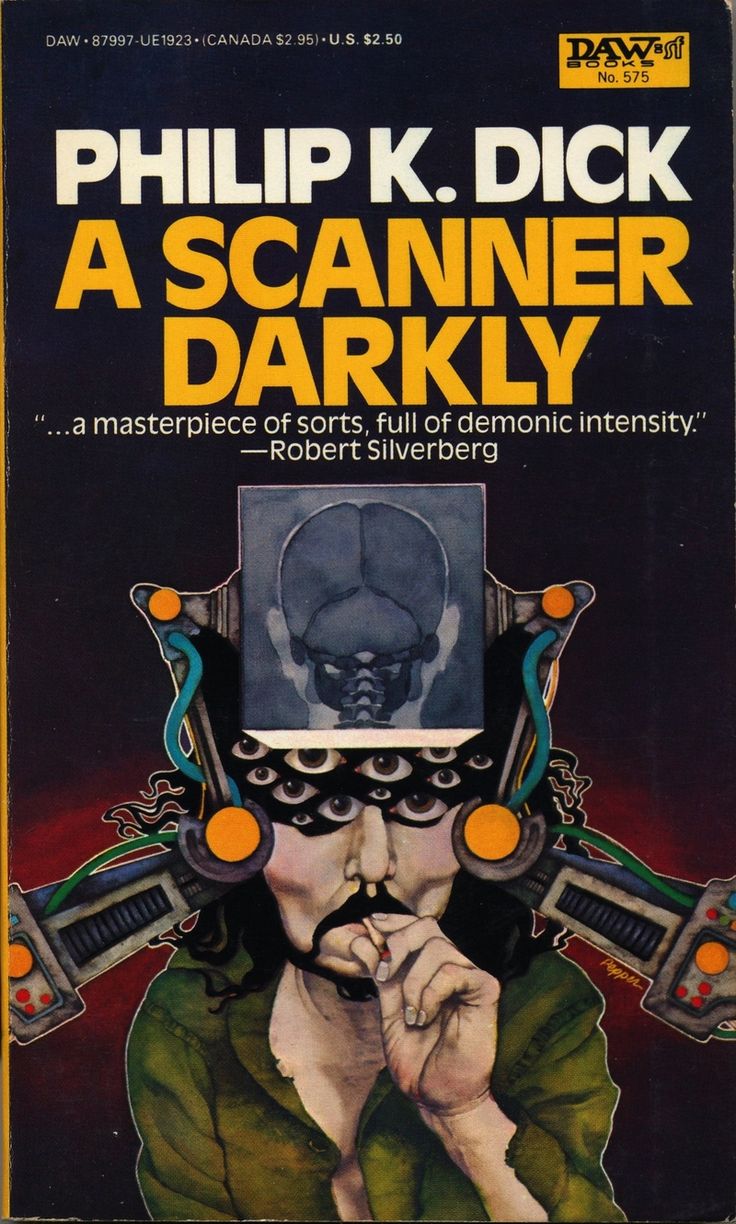

Though DAW’s edition of A Scanner Darkly came out in April of 1984, its cover drips with the hazy aura of American freak culture in the 1970s. The figure on the DAW cover, with his desperate look, his compulsion, and his brain-scanning gear, certainly reflects themes in PKD’s book. But it also presents a portrait of the reader, or a possible reader: a white male longhair getting high, seeing through other eyes, and sinking into the sort of cavernous headphones favored by PKD and other audiophiles of the era.

I use the term freak quite consciously. First injected into circulation by Frank Zappa in 1966, freak captures the experimental, surrealist, anti-authoritarian, and all around less wholesome dimension of the counterculture. Hippies read The Hobbit; freaks read H.P. Lovecraft and Philip K. Dick. Barris, the Scanner character possessed of weird and funny raps, is a freak. Emerging at the crossroads of drugs, the pulp imagination, culture hacking, and media tech, the freak was perfectly poised to both write and consume SF.

The image was created by Bob Pepper, who did a string of tense, evocative PKD covers for DAW starting in 1982. In an interview, Pepper claims doing six PKD covers, but I only know of four other than Scanner: Ubik, Three Stigmata, Deus Irae, and A Maze of Death, which is the most beautiful besides this one. Pepper started illustrating in the early 1960s, and floated his art on the streams of the counterculture, which was defined as much by the sorts of images it created and consumed as by anything. Pepper’s most famous work in the 60s was the lysergic cover of Love’s album 1967 Forever Changes, a dud at the time but now wisely regarded as one of the most visionary albums of American Psychedelia ever. (As Andrew Hultkrans argues in his great 33 1/3 book on the album, Arthur Lee’s lyrics are also gnostic as hell.) In the 70s, Pepper did a number of covers for Ballantine’s great and powerfully influential fantasy paperback series, edited by Lin Carter; of special note are his trippy-drippy covers of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast Trilogy.

The melty lines and floating eyes of the Scanner image mark Pepper’s art as a product, at least indirectly, of the drug culture, which transformed modern illustration through its embrace of fantasy archetypes, Art Nouveau organicism, and concrete otherworldliness. But by straight-up depicting a moustachioed stoner smoking weed, Pepper also puts the drugs out in the open. (In a sense, this directness was similar to the move that Richard Linklater made when he cast three notable drug users, Robert Downey Jr., Woody Harrelson, and Winona Rider, in his film adaptation.) For me the frankness of Pepper’s image—at once goofy and kind of disturbing—announces the uncomfortable fact that, whatever else he was, PKD was a druggy writer. He took drugs, he wrote on drugs, he wrote about drugs, and he moved in and out of social scenes where drugs were forms of bonding and pleasure, as well as avenues towards self-destruction, madness, and alienation.

I use the general term drugs advisedly. Most of the time it’s a sloppy word with little information content, but in this case, the more specific you get, the more you miss. PKD had his preferences, and was no stoner; as far as I can tell, he experimented little beyond his core love of speed, which helped fuel his writing spells as much as it helped Jack Kerouac or Jean-Paul Sartre. But though it was useful, speed was also a bohemian drug, a reflection of PKD’s long life on the edges of California bohemia. But his personal use isn’t really the point. To use a term created by another guy who spent a lot of time in California, PKD grokked drugs. His fictional concoctions, from Chew-Z to Substance D to all those amphetamine dispensers in Ubik and The Zap Gun, etc., embody and reflect the culture and metaphysics of the drug culture–even if he wasn’t always very happy with their effects on him or his friends.