Latin American sea shanty tales

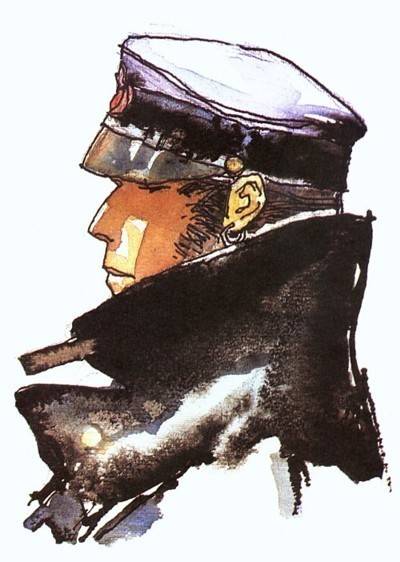

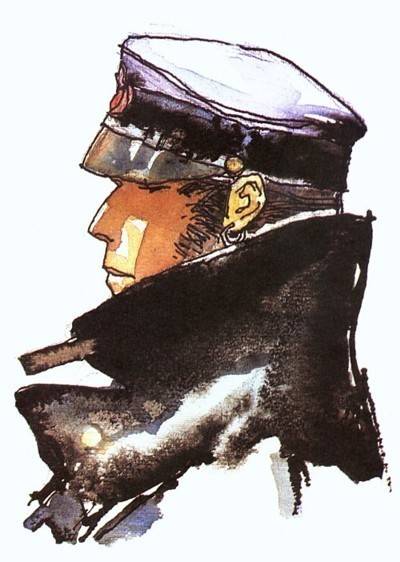

Lore has it that my college buddy Chad McCracken showed up freshman year toting three well-thumbed books: a King James Bible, The Portable Nietzsche, and the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook. Almost two decades later, and more or less out of the blue, Chad sent me a copy of Álvaro Mutis’ The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll, a fat, tiny-typed collection of seven novellas about an appealing but world-weary seafaring adventurer of indeterminate origin named Maqroll the Gaverio (the Lookout). It took me far too long to get to the book. I don’t get to read fiction as much as I’d like, and half of the novels I get around to are by dead people, and half of the ones I pick up at all I never finish. You could say I lack follow-through, but it’s really driven by a demanding hedonics: there is so much fiction out there that if I am not instinctively compelled by a book, if I don’t in some sense fall in love with the story and the prose—and it usually has to be both—then there is no reason, short of social obligation or a paycheck, to keep on reading. So I don’t.

No such worries have attended my consumption of the tales of Maqroll, which are so delicious, so playful and wise and sad and smart, that I am forestalling finishing the final novellas out of literary greed. (As of last word, the eighty-plus-year-old Mutis was said to be working on an eighth story, which means that Maqroll fans, like the cheerfully melancholy nomad himself, will be able to steer our leaky tramp steamers towards that next prize, even though, like our hero, we know we face rapidly diminishing returns.) Mutis was born in Colombia, but lives in Mexico, and from this nifty Francisco Goldman interview I suspect he enjoys fine tequila very much and has lots of excellent friends. For most of his life he wrote poetry, which doesn’t pay any more in Latin America than the U.S., and so he worked for a great deal of time as a PR flack for Standard Oil in Columbia and then as a Latin American point man for Hollywood. He traveled tons, and those travels, that poetry, and some bejeweled narrative genius that owes its ultimate source, I suspect, in Sheherazade, led him, late in life, to invent, or discover, Maqroll—a figure of such great sympathy, such tangible but elusive appeal, that I am not surprised in the slightest to find out that, to his friends, Mutis speaks of the sailor Maqroll as a real person.

This is the parafiction that Mutis adopts in his stories: that the author is a poet-cum-oil man piecing together fragments of the life of the friend who only occasionally crosses his path. The frame stories that Mutis builds around Maqroll’s stories of failed gold mines and Leventine smuggling and peripatetic loves recall the formal spell of the fable, of the tale within a tale, and this lends Maqroll’s narratives, despite their particularity, a universal, almost mythic character. Often the description of a ship or a jungle or a woman shimmers with such preternatural presence that the images seem magical despite their evident birth in our quotidian world. In “The Tramp Steamer’s Last Port of Call,” Mutis describes his synchronistic encounters with the decrepit steamer Halcyon before meeting its aging Basque captain, who in turn tells the narrator about his perfect, and therefore perfectly tragic, love affair, which of course obliquely involves Maqroll. It is a perfect modern sea shanty, its first four pagses alone seeming to both carry and exceed our life, like the single story you get to take with you to the afterworld. And yet, Mutis has no truck with anything like magical realism, that besotted schtick that so many Latin American authors now labor under. Maqroll is a dreamer, but he wonders in a dreamless modern world of cheats and cops and crazy women. He makes poor decisions, watches friends die lousy deaths, and takes what comes. He reads obscure books about European history to escape the sorts of decrepit places and nauseating tedium that awaits a man in his line of drift.

As its English title indicates, The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll are essentially adventure stories, even boyish ones at time. This is a world of travel whose proximity to real labor and modest gains keeps the poison of the Lonely Planet at bay. Mutis’ loving and detailed description of port towns and warfside meals and crappy hotels—lusciously translated by the indefatigable Edith Grossman—inspire wanderlust, or at least a Conrad-worthy conviction that the world only reveals itself when you have committed yourself to a real line of flight. But there is an essential, wise sadness here as well, and in his frank and unromantic evocation of the ever-beckoning world, Mutis conveys the same lyrical detachment that I taste in Pessoa, that Buddhist yet modernist awareness of impermanence and the impersonal spark that such awareness lights up within us. As Mutis writes of his recurrent sightings of the tramp steamer Halcyon:

This is how we forget: our affairs, no matter how close to us, are made strange through the mimetic, deceptive, constant working of a precarious present. When one of these images returns with all its voracious determination to survive intact, then what learned men call epiphany occurs: an experience that can be either devastating or a simple confirmation of certain truths that allow us to go on living.

The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll is full of such images, images that return, riding the crest of epiphany, before they dissolve again into the same old brackish sea of dreams.