Magnetic Fields, back in the day

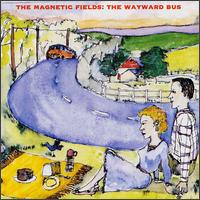

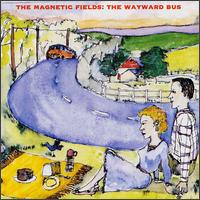

A young couple picnics at the side of a country road. They’re dressed like English majors and they’re lost in thought, gazing off at a solitary snowy mountain in the distance, set against a reddening sky. The treats on their blanket are beautifully arranged. They do not see the bus that’s careening their way.

It’s all here on the watercolored cover of the Magnetic Fields’ The Wayward Bus: introspection, space, sweet afternoons, death just over the hill. Though Susan Anway’s vocals radiate much of this rich glow, the band is essentially the solo project of Stephin Merritt, a homegrown Bostonian synth tinkerer who splices and folds his tapes into origami pop worlds as entrancing as they are singular. Magnetic Fields’ artier 1991 import (included on the new CD) was called Distant Plastic Trees—a perfect title, since Merritt makes some of the most organic synth-pop I’ve ever heard. His keyboards are moist and squelchy, like violins and calliopes and nameless analog machines stolen from the Young Marble Giants all singing in the depths of a dark, mossy well. Below these swelling, scented gusts, Merritt’s drum machines chug along, the beats textured with crickets and bubbles and winding clocks.

While you can hear early ‘80s Anglo synth-pop here, Merritt’s a pretty original guy, and besides Brian Wilson’s pocket symphonies, his only direct point of reference is the teen love utopia of Phil Spector. The title of the opening song, “When You Were My Baby,” says it all: “Be My Baby” in past tense. “The Saddest Story Ever Told” bites the first few bars of the Crystal’s “Then He Kissed Me,” but here the sleigh bells, tuba, and dopey keyboards are as shimmery and insubstantial as last summer’s gropes, and Anway confronts her lover as he heads for the door, her truths so bitter she doesn’t even get angry: “You’ll see the world / Diving for a girl you’ll never find.”

The Magnetic Fields look at young love with the eyes of time, and Anway sings like she’s suspended between present pain and the opium of reverie, her melancholy as catchy as the tune. Merritt realizes that in collecting snapshots of the past, you recover a hints of its scent (as one particularly golden chorus demonstrates: “Autumn leaves, diaries, Tennessee and Jeremy / Suddenly, willow trees, memories of Jeremy”). But often this Moog-loving Proust drags up the jagged driftwood of dream instead, and his lyrics—“Raspberry schnapps, like a thousand sunsets,” “Whale embryos filled your enormous room,” “Like a Galapagos turtle we grow old and stay that way”—are all the more surreal for not sounding drug-induced. Acute sensitivity is Merritt’s drug, and references to Isadora Duncan, Pippi Longstocking, discos and Fabergé eggs make Morrissey seem like a hairy-chested wild man.

Dusk haunts this record, slit wrists and tidal waves and summer lies all expressing the same inexorable fade. Even the goofier upbeat numbers like “Tokyo a Go-Go” and “Falling in Love With the Wolfboy” seem disembodied. Like a post-everything Neil Young, Merritt sees the rust in the flush of youth—as Anway sings in the translucent “Lovers From the Moon,” “They say we’re too young / I think we’re too old.” This twilight coats everything from teen suicide to the lameness of being twenty-something to the inexplicable popularity of the Cure, and Magnetic Fields turn it into art, these Dada watercolor postcards from the land of the long eclipse.