A summer reading list

Sometimes I am overcome with the desire to have spent my twenties as a derelict vagabond, or a devoted monk, or an apprentice to an oud master or biodynamic vintner. But I mostly spent my time doing what I did, which involved a lot of freelance writing and lecturing and talking with people. I still sometimes yearn for a life richer with remarkable experiences, but what I definitely got was a life rich with remarkable people — with friends and colleagues and characters. As I was poking around for a good topic for this early summer post, I realized that a lot of these people had published books of late. So while some of these works are too weighty or arcane for the beach, here is a reading list for the magickal summer of ‘23.

(•) Hear ye, hear ye: after a myriad of moons, the esoteric publisher and herblore master Daniel A. Schulke, author of the notorious Viridarium Umbris: The Pleasure Garden of Shadow and master of Sabbatic witchcraft, has released his long-awaited tome The Green Mysteries: an Occult Herbarium on his own Three Hands Press. Featuring over 400 entries, the book delves into the occult lore of plants from both New and Old Worlds, providing botanical insights alongside personal accounts of feral workings and charts of occult correspondences inspired, at least in part, by Dale Pendell’s similar treatment of psychoactive drugs in his brilliant Pharmako series. (Dale and Daniel were friends and birds of a feather.) The Green Mysteries is also a hefty work of magical book art, printed entirely with offset lithography, and packed with gorgeous calligraphy and a few hundred illustrations by Benjamin Vierling, a Californian artist of meticulous visionary detail best known (in my world, at least) for painting the cover portrait for Joanna Newsom’s Ys in the painstaking old master style he favors. (Years ago, I interviewed Benjamin for my enormous Arthur profile of Newsom.) There is a whole world of lavishly produced contemporary grimoires out there, which feed the hungers of all manner of edgelord fetishists, but the green animism that characterizes Schulke’s work and knowledge base run particularly deep.

Like many an esoteric book-buyer, some of whom have grown quite grumpy over the years, I ordered my special edition of the Mysteries a long time ago, and probably won’t get my hands on it till June. Though I could have checked out a review copy for this post, I am waiting to encounter the charmed arcanum in my fleshy hands. But I wanted to mention the book here because even the trade edition may sell out soonish. Also, in light of my recent chapbook The Pleasure: Animist Encounters with Poison Oak, which briefly discusses Schulke’s work, I could not help but note that the Vierling illustration that appears on the Three Hands webpage for The Green Mysteries looks very familiar, and these are the sorts of leafy signs Schulke teaches us to follow.

(•) I met the poet, essayist, and fiction writer Miranda Mellis around the time I read and wrote about her surreal and wonderful first book The Revisionist. I guess you’d have to call her an experimental writer, but her witty, playful, and brainy stuff has always struck me as close to home. Her latest publication is The Revolutionary, a chapbook from the poetic micropress Albion Books. A delightful and sometimes devastating interweaving of memoir, essay, and aphoristic meteors coursing across spare pages, The Revolutionary riffs on Mellis’s own experience growing up in a radical household in the ’70s and ’80s, before it turns to the more recent death of her dad, the remarkable civil rights attorney Dennis Cunningham. What is a revolutionary? For Mellis, who saw no wall decorations growing up that did not relate to the struggle, revolutionaries are time travelers, or untimely travelers, channeling futures with transpersonal identities that would paradoxically dissolve if they were to succeed in their efforts.

Mellis’s sympathetic but sometimes pained meditations on this revolutionary spirit — which “long[s] for justice, equality, and fairness, as if for the beloved” — grow more urgent and universal as she enfolds us into the last lingering days of her dad’s life. Caring for him offered her family a “school for the living by the dying,” a revolutionary cell of patience and tension and radiance where “love sobers up.” We read and write too infrequently about mortality, and especially at the tempered and nourishing pitch that Mellis favors here. Her words are honest, lyrical, and earthbound, “formations of pain like ink clouds, at once saying something and obscuring something.”

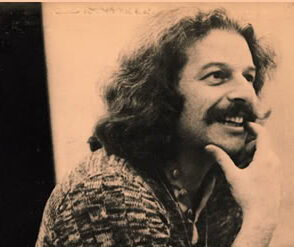

(•) The Revolutionary was written, metaphorically at least, from the side of the deathbed. With Last Words: Towards an Insurrection of the Poetic Imagination, the other shoe drops. Diagnosed with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma a week before he turned seventy, and electing to skip chemo, the provocatively magickal writer, theater-ritualist, and fiercely independent filmmaker Antero Alli offers up this short, inspiring, and spiky reflection on his own sovereign creative life. Like Robert Anton Wilson, Alli grokked the most radical implications of Timothy Leary’s philosophical practice, and poured his self-meta-programming research into the esoteric underground with mind-bending manuals like Angel Tech and The Eight-Circuit Brain (which is the most satisfying account of Leary’s Eight-Circuit Model out there). Schooled in the mysteries, Alli also earned his keep as an innovative postmodern astrologer. In order to undercut culty dependency, he hewed to a rule I always admired: clients were limited to three readings in a lifetime. Since I maxed out long ago, I am very glad to have some more readings here, oracular tidings from a wise old triple Scorpio who is still a “babe in the abyss.”

Alli pursued the creative life to the hilt, and indeed continues to do so til the end, combining a love of experimental collaboration with a tenacious independence and a hermetic hotline to the Mystery. Ernst Jünger might call him an “Anarch,” but he is an Anarch without machismo, a tenacious (and enormously productive) servant of the Muse who keeps falling into enchantment with the world, with work, and with the insurrectionary potential of the imagination. Last Words is a short book oozing a rich life, its modest collection of poems, rants, and recollections radiating an immodest amount of joy, obsession, esoteric insight, shadow-work, and intensity. The book’s haunting photographs and afterword are provided by his long-time partner Sylvi Alli, a musician and singer with whom he sought to “reinvent Romance” through the pursuit of an “Art Life” worked in mutually supportive parallel. It can’t have been easy, but I’d say their quest was fulfilled in spades.

(•) I’ve had many adventures with Mike Jay over the twenty odd years we have been hanging out, so I am biased, but he remains my favorite historian of drugs in the modern world. Jay is another fiercely independent soul, and he writes from a charmed and singular perch between academia and journalism, subcultural sympathy and intellectual skepticism, and he knows a great deal about crucial related fields like medicine, literature, and psychiatry. Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind is his pandemic project, and a good example of how that isolating bummer could spark some great creative work. Prevented from spelunking through the British Library and other archives, as is his wont, Jay took a step back and surveyed the whole zone he has been covering for decades. The result is a kaleidoscopic array of dense but fluid narratives, organized by substance and packed with colorful personalities, and collectively offering a crucial argument with significant implications: that psychoactives have played an absolutely central role in the experience and self-understanding of modernity. Psychonauts is particularly keen to show how, in contrast to the double-blinded “objectivity” of contemporary scientific practice (which doesn’t always work for psychoactives), researchers have more traditionally embraced self-experimentation, which in turn entwined their forays with the fringier adventures of bohemians, aesthetes, and esotericists. But of equal importance here is Jay’s consistent reminder that some seasoned Euro-American psychonauts—such as the fascinating James S. Lee, whose Underworld of the East memoir Jay helped resurrect in 2000—evolved sophisticated and (reasonably) safe modes of psychoactive use that eschewed mysticism and exoticism for perfectly secular modes of modern enjoyment that nonetheless push the envelope of mind and self.

(•) The subtitle of Alexander Beiner’s new book, The Bigger Picture (Hay House), is How Psychedelics Can Help Us Make Sense of the World. In light of the triple-fudge hype that currently smothers psychedelic discourse, it’s easy to imagine Beiner’s publisher urging something punchier, something more along the lines of How Psychedelics Can Help Save the World — which is, unsurprisingly, already the name of a collection of essays published last year. But the difference is telling. For his first book, Beiner could easily have played the smart-aleck psychedelic warrior — after all, he already shaped online discourse with the controversial Rebel Wisdom project he co-founded. He participated in Imperial College London’s intravenous DMT trial, which had participants dribbling those bejeweled basketballs for a solid half hour, and even lives on a houseboat along a canal in the city. So cool!

But such a pose is totally not Ali’s style, which is even-handed, open-minded, kind, and thoughtfully vulnerable. We do get some righteous trip tales in the book, as well as some hard-won considerations about the limits and traps lurking in such outlandish visions. But most of his book presents a balanced and insightful passage through the current psychedelic zeitgeist, a multi-perspectival journey that is critical, compassionate, and mind-expanding in equal measure. Beiner absorbs and plays off of scores of thinkers, pundits, and memeplexes, weaving a meshwork of connections that paradoxically helps clear the space for a new clarity. If Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind was a guide for the curious, The Big Picture is a guide for the newly initiated. While cannily showing how psychedelic shamanism can help us navigate the Internet and its careening reality tunnels, Beiner also undercuts the scene’s tendency toward delusion and messianism. At the same time, he steps beyond the capitalist realism of today’s corporadelics toward a social and ontological transformation he calls “reverential revolution.” Accessible, open-hearted, and clarifying, The Big Picture is a panpsychist tonic in an increasingly noisy and narcissistic space.

(•) Brian Chidester is a writer, archivist, and documentarian who correctly calls himself a “creative historian” — a time-digger who is at once passionately imaginative and nerdy with detail. I have already written on the Shore about Brian’s near obsessive work on Eden Ahbez, and long admired his stuff on Burt Shonberg, the Beach Boys, and Bruce Conner. (By the way, Brian and Domenic Priore have completed an amazing illustrated book on psychedelic surf culture that is just waiting for a publisher willing to break out the checkbook.) Brian is great at discovering hidden veins of underground wonder and articulating their significance, which very much includes the remarkable work collected in his latest book Out of My Head: The Imaginary Creatures of Josep Baqué (Norton/Fantagraphics). Baqué was a police officer in Barcelona, and drew reams of fantastical creatures that he kept totally under his hat. The monsters recall Dr. Seuss animals, the ratfinks of Stanley Mouse and Ed Roth, and the art of Weird Tales, but they possess an entheogenic clarity and novelty all their own. Though Chidester provides some juicy framing essays about this remarkable visionary art, for the most part he lets Baqué’s chimeras speak for themselves.

(•) Lastly, my old friend Harlan Emil Gruber has finally self-published a book long in the making, a study of sacred geometry and his own architectural experiments entitled Portal to the New Earth. Harlan has been making art and exploring strange scenes as long as I have known him, which is around thirty years now; though we can’t agree on where we met, I can guarantee it was in some spray-painted corner of the NYC underground in the early ’90s. A car nut, Harlan once made mandalas out of images of hotrod engines, as well as a series of psychedelic drug patches done in the style of grease-monkey logos (Valvoline became Ketamine). He also built a brilliantly minimalist analog feedback drone device out of a bass guitar and a speaker and dubbed it the Quasar Wave Transducer. For his early years at Burning Man, Harlan built practical social platforms, constructing ingenious camps with good central kitchens, crafting playa-worthy bikes, and modifying his Dodge van with a rooftop deck that provided me and other pals with ungodly amounts of fun.

Then Harlan moved on to the Portals, a series of playa installations based on sacred geometry—sometimes supported by Burning Man art grants, sometimes not. Alongside David Best’s temples, Harlan’s Portals were to my mind some of the most successful social architectures I experienced on the Black Rock — particularly the 11:11 Diamond Portal and the Sapphire portal, which catalyzed all manner of unexpected encounters and happenings. Over the years Harlan’s Portals have started popping up at other festivals, but Portal to the New Earth reveals the utopian visions behind his constructions. I can’t follow Harlan all the way down the crystalline corridors of his New Age metaphysics, but his overviews of fantastic architecture and cosmic pattern language are engaging, and I have mad respect for his persistence of vision and the archetypal clarity he brings to his temporary autonomous zones. Just step on in.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. These pieces and updates come when they do, and I dodge the crushing anxiety of the hamster wheel by not offering paid subscriptions. But you can always drop a monetized appreciation in my Tip Jar.