My old pal Scotto Moore—madcap sci-fi author, a cappella genius, and co-instigator of a 1990s Internet drug cult so secretive my brain automatically blocks out its name—is a music video and short animation obsessive. He tracks the art so assiduously that he looks at you blankly if you ask about the latest Marvel movie or Netflix cult doc, like you were talking about cattle inventories written in cuneiform. He publishes a newsletter called This Newsletter Cannot Save You, a biweekly pop rocket of distraction that collates his latest finds, “lovingly sifted from the obscene barrage of content that comprises life in the logosphere.” If you share Scotto’s taste for bent marvels and bleak hilarity, I herein submit a strong recommendation.

Last summer, Scotto’s missive linked to a music video for the “swamptronica” band Dirtwire’s cover of an old soft rock classic, America’s “Horse with No Name.” I don’t know what swamptronica means; the band plays the charmingly bland 1971 hit pretty straight. But the images—the work of Stable Diffusion artist Optimoos, who seeks to “unlock the infinite possibilities of AI animation” according to his Youtube channel—was, as the newsletter promised, rather mesmerizing. I decided to write about it right away and then got caught up with other things. Like so much snackable content these days, I was prepared to release this weird iridescent fish back into the torrent of the obscene barrage and just forget about it. But I kept thinking about the thing, and sharing the video, even if my initial amazement gave way over subsequent watchings to a cooler appreciation of its pop futuristic sorcery. Give it a toke, at least for a minute or so:

Whoah, trippy. But what does it mean to describe this video as trippy, aka, as psychedelic? There are multiple layers of psychedelia here, and I think it’s worth teasing some of them apart. It might help shed some rainbow light on the enigmas of psychedelic visual experience, as well as the psychoactive dimension of AI image production.

Perhaps the most genius layer here is phenomenological. I suspect that many psychonauts will nod their heady heads in face-melting recognition of the phantasmagoria on display here, particularly in the video’s opening minute. One feature of psychedelic visual perception is that, while well-defined forms can remain relatively stable—like the shapes of horse and rider—the semiotic edges and stylistic fills of these figures are constantly looping and mutating, unleashing both novel features—weirdness—and a sometimes dense procession of symbols, references, and allusions.

Here the rider flickers between genders and eras, evanescently suggesting a medieval knight, an Indian warrior, a Marlboro ad, a space cowboy, a Taos hippie, Paul Kirchner’s Dope Rider, and maybe that horse girl you had a crush on at summer camp. This sort of semantic multiplication also enchants the surrounding desert landscape, particularly in later portions of the video. The weathered mesas and suggestive rock piles that have long haunted desert visionaries—including the great John Ford, who kept returning to magical Monument Valley to shoot his classic Westerns—transform into alien artifacts and ancient machines, concretizing the sense these geological features already have of being crafted rather than naturally produced.

Of course, the rapid transformation and evocative multiplication of related shapes and styles lies at the heart of AI image production as well. The variable responses to prompts are often fashioned through relations of likeness, resemblance, and similarity. Resonant shapes—stable diffusions—are brought to the fore. In filmese, you call these sorts of morphological juxtapositions match cuts or graphic matches, and while they may be purely formal, they often carry a symbolic or thematic charge. While the following famous match cut, from the opening scene in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, is not particularly trippy (or particularly exact), its symbolic as well as formal weight lends an apocalyptic charge to the visionary content of the film.

In psychedelic perception, graphic matches are usually sewn together not through montage but through continuous transformations—the bone melts into a space ship. When these metamorphic shapes also mean stuff—as in the Kubrick match cut—the wit and wisdom (and sometimes perversity) of psychedelic perception is born. In the Dirtwire video, we encounter this graphic play most vividly from 2:23 to 2:47, when fruiting mushrooms and octopi infest and stylize each other’s bodyshapes. Not only do their shapes resonate, but their symbolic content does as well—while mushroom caps are obviously trippy icons, cephalopods signify ecstatic group-mind groks—at least according to Terence McKenna, who argued that these animals, in communicating through the changeable surface of their skin, auger a future of instant liquid semiosis—a semiosis not unlike these very roiling shapes.

The Dirtwire video unfurls these metamorphic changes at a certain pace, which often feels spot-on to me: a relentless flux that recalls hardcore tripping’s distinctive blend of Dionysian visual excess, fractal iteration, and the woozy suggestion of an underlying emptiness behind or beneath the carnival show. But here there is a futuristic twist as well. While the unfolding pace recalls the human imagination on a few hundred mics of LSD, it also gestures towards AI’s inhuman rate of ceaseless image production.

Finally, as most subtly, Optimoos also gestures towards the uncanny way that psychedelic perception can sometimes radically reframe the visual landscape without altering its details much, a “meta” mise-en-scène shift that recalls film effects like depth of field variation, or, more exactly, the dolly zoom. Optimoos stages this effect wonderfully in the passage between 0:50 and 0:55, but it only really worked for me the first two times I saw it; in subsequent viewings, my anticipation of the movement of the virtual camera dissipated the earlier shudder of recognition. And this loss of enchantment is also something to keep in mind—phenomenologically accurate trip visuals often lose their punch through exposure, just as the mind-bending “bullet time” effect in the Matrix movies rapidly devolved into a commercial contrivance to sell vodka and luxury cars. Magic is magic, but it’s also a trick.

Optimoos worked hard on this puppy. It’s not like he just pressed play on the generative AI button and got balls-to-the-wall pop psychedelia. At the same time, the neural networks behind programs like Stable Diffusion seem preternaturally good at mining tripping space, something we have known since Google’s Deep Dream program unleashed its “algorithmic pareidolia” on all manner of images (including Trump, below) almost a decade ago.

There may well be a strong correlation between how psychedelics affect perception and how algorithms generate pattern recognition and image production in neural networks. Psychedelics may decohere brain regions in a way that increases entropy in the visual system, unleashing a storehouse of images as the brain attempts to predict and fix the magma of its now molecular perceptions into relatively stable forms. AI is also good at forging patterns (or “embeddings” in the lingo) from mountains of data, a less than rational logic of associational coherence that nonetheless characterizes a lot of human thought and aesthetic play.

Such associational patterns also strongly characterize visionary states, the variation of Jungian archetypes, and the symbolic “correspondences” that haunt magical thinking and practice. This may be very important. A recent New Yorker profile of the artist and musician Holly Herndon, who has made spiky and significant interventions in AI with her partner Matt Dryhurst, begins with the couple’s discovery of a Virgin Mary shrine in Spain that featured Mary iconography from around the world: “a faceless, abstract stone carving from Cameroon; a pale, blue-eyed statuette from Ecuador; a Black Mary from Senegal, dressed in an ornate gown of blue and gold.” Despite this variety, all these figures are avatars of Mary, features of her particular embedding in data space and archetypal iconography alike.

Of course, one person’s archetype is another person’s cliche. And while the Dirtwire space cowboy does roam the cosmos, he also frequently crosses the border into kitsch. And no wonder—left to their own (psychedelic) devices, generative AI’s image machines will conjure an ungodly amount of cheesy images. I mean cheesy here not in the sense of porny—although there is plenty of that hovering in the wings—but of easy, lazy, iterative, cliched. Illustration—as opposed to fine art—often flirts with cliche, of course, since a lot of illustration, both commercial and fannish, offers little more than stylized variations on a theme. AI in this sense is the ultimate illustrator (as opposed to artist), since it provides nothing but such variations: neither singularities nor copies, novelties paradoxically devoid of novelty.

In a recent interview with Sam Altman, the visionary artist Android Jones described AI as the McDonald’s of art: “it doesn’t really have a soul, it’s really beautiful, it tastes good, its sugary, but there’s no real substance behind it.” Indeed, it is easy to imagine those golden arches rising up over the scintillating desert mesas in the Dirtwire video, amidst all the rainbows, temples, and kaleidoscopic mandalas. Psychedelic art, which is generally closer to illustration than fine art, is particularly vulnerable to kitsch, as the aesthetic in headshops can easily approve. Even though I admire the freshness of some familiar imagery in the Dirtwire video, it can’t hold a candle, say, to the imaginative world-building in the recent animated series Scavengers Reign, whose extraordinarily bizarre (but strangely familiar) flora and fauna present a sometimes intensely trippy amalgam of beauty, horror, and organic life that surprises as well as delights.

But here’s the rub: closed-eyed visuals on psychedelics themselves can get pretty kitsch. For all the hyperbolic arabesques and dense symbolic landscapes, there are icons and abstractions alike that seem corny, cheesy, cliched, a sort of plastic Kmart eye candy. The French artist and writer Henri Michaux articulates some of this marvelous tedium in his fascinating 1956 mescaline account Miserable Miracle, where he laments “the lines, the lines, the diabolical, dislocating lines.” In a recent Psychopolitica post, Nikita Petrov captured this strange juxtaposition when responding to a reader about smoking DMT: “It feels very profound, but sometimes people feel let down that all this profundity takes form of a fucking cartoon.”

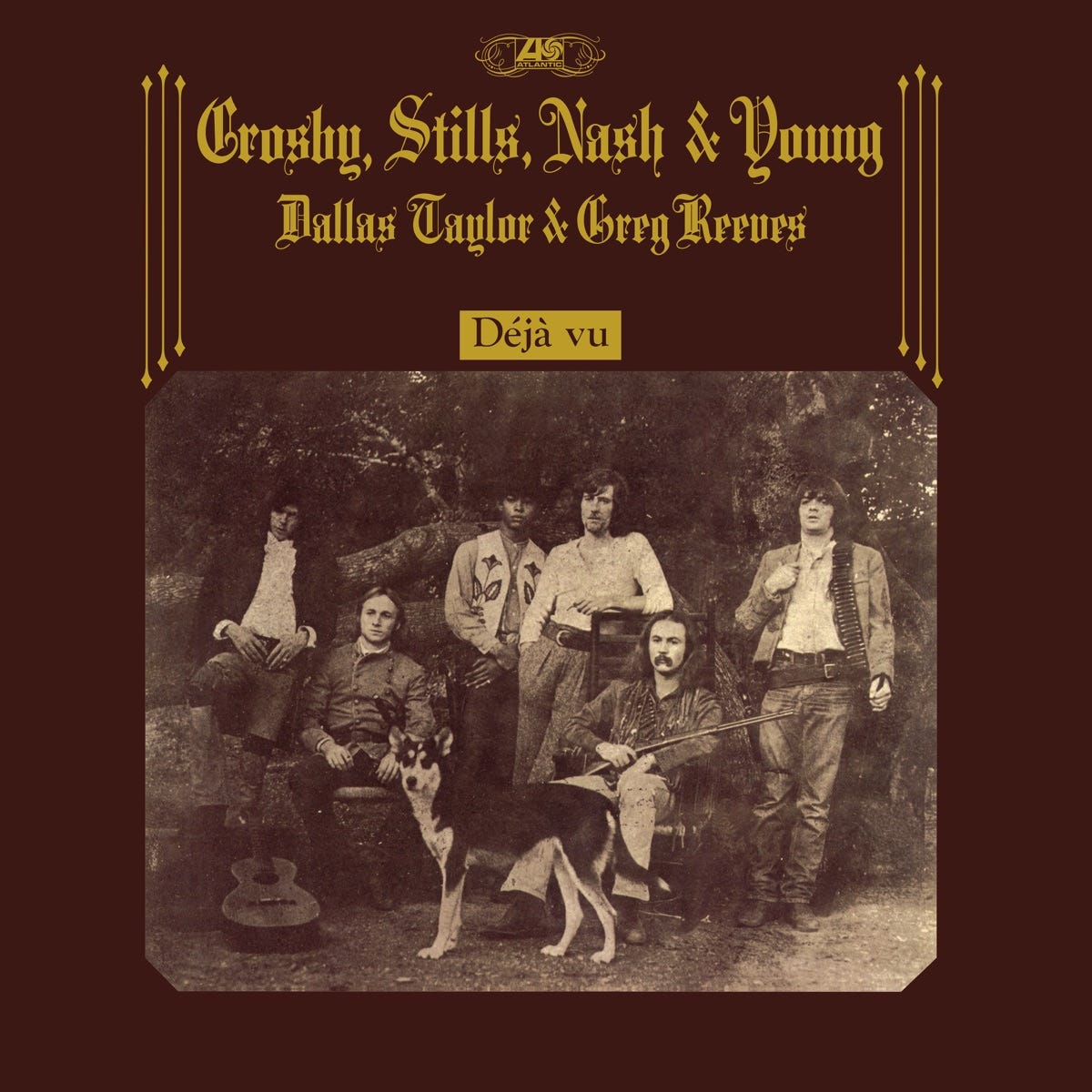

Part of the genius of the Dirtwire video, though, is the way that Optimoos paradoxically constrains the kitsch by working through a cultural category that is proximate to both archetype and cliche: the category of genre, and specifically, the acid Western. America’s “Horse with No Name” is itself the result of 60s bohemians appropriating Western styles from the grip of country music’s largely conservative codes. These styles have less to do with the cowboys and lawmen that starred in the TV oaters this generation grew up on than with the rough-and-tumble bit players in the narrative margins: gamblers, bandits, Indians, mountain men, drifters, drunks. Such vibes would later achieve mass memeification through the cover of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s 1970 album Déjà vu, cementing an association that, suitably toned down and infused with varying degrees of actual country music, would help shape the aesthetics of bands like the Eagles, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Pure Prairie League, Workingman’s Dead–era Grateful Dead, and America, at least in their “Horse with No Name” hit.

Starting in the 1950s, Hollywood started to make revisionist Westerns, downbeat or existentially driven films that pushed backed against usual triumphalism. In the 1960s and 1970s, some revisionist Westerns grew distinctly countercultural in ethos. These longhair films weren’t always druggy—in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Kris Kristofferson’s outlaw is a hippie hedonist, but the film never transcends Peckinpah’s gritty nihilism. Other freak Westerns got pretty far-out. In his book on Jim Jarmusch’s extraordinary Dead Man (1995)—one of the greatest psychedelic Westerns, albeit from a later era—Jonathan Rosenbaum devotes a short chapter to the “acid Western.” Pauline Kael first deployed the term in her 1971 slam of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s crazy El Topo, but Rosenbaum capaciously revivifies the term to describe a “cherished counter-cultural dream” that inflects a number of cool movies, including Monte Hellman’s The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind (both 1966), Robert Downey’s very weird Greaser’s Palace (1972), and of course El Topo.

As Rosenbaum makes clear, we are talking about a “generic ideal” here rather than a clearly defined and well-populated genre. I don’t even agree with his short canon. The Shooting, with its bleak desert setting, doppelganger twist, and and jagged time-slice editing, is deeply acid-damaged. But Ride in the Whirlwind, though wonderful, is less trippy even than Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), which Rosenbaum calls a “pot Western” rather than an “acid Western.” Fair enough, but Rosenbaum also includes a number of films that aren’t strictly speaking Westerns, like Jim McBride’s post-apocalyptic Glen and Randa, Hellman’s amazing Two-Lane Blacktop, and Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, all of which came out in 1971. OK, I will sorta give him these, especially the Hopper. But Rosenbaum doesn’t even mention Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand from the same year, an actual Western (and a fine quasi-feminist one) that features exquisitely sensitive psychedelic interludes courtesy of cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond:

I could geek out on this shit for weeks, but here is the point: as Rosenbaum insists, the acid Western is primarily an unfulfilled fantasy. A variety of films, both Westerns and not-quite Westerns, take swipes but can never occupy the “cherished counter-cultural dream” space for long. The Shooting is too scrambled, El Topo too pretentious, Dead Man too wry. More recently, we have the example of Jan Kounen’s Blueberry (2004), which the scholar Patricia Pisters argues is the first example of the genre to look forward to today’s psychedelic renaissance, with the film’s emphasis on healing rather than spiritual drift and rebellion. Kounen himself spent a lot of time drinking ayahuasca in South America, and the influence shows—literally. Though the brew has no business showing up in 19th century North America, the trip visuals that accompany the final healing ceremony are totally on the money, and still amaze after twenty years of CGI development. But the rest of the movie sucks donkey dick. Another miss.

The closest I ever came to satisfying my own acid western dream was one summer afternoon I spent on some cubensis in the Los Padres National Forest northeast of Santa Barbara. My pals had a great protocol. After munching a solid ambulatory dose, everyone would go off on their own for a couple hours before a signal would go out and we would reconvene for some high plains grokking.

So there I was, stumbling through the alders and sycamores by a mostly dry creek. I was pretty raw, having just undergone one of those cracked healings fungi can provide. I had been thinking about my paternal grandmother, who was still alive but lost to Alzheimer’s, and I realized that the nana I loved was gone for good, and so I dropped to my knees in the sand and grieved. Aimlessly wandering afterwards, keeping to the shade, I heard the signal: a lonesome wail on a minor key harmonic expertly wielded by the one good doctor among us.

The nod to the Ennio Morricone score for Once Upon a Time in the West triggered an extraordinary effect. I gazed up at the canyon walls, whose sere rock and blooming yuccas were now tinged in the sunset haze of 1970s film stock, and remembered that a mounted posse was hot on my trail for a murder I did not commit, and that salvation lay in desert, where there weren’t no one for to give me no pain. In a meta flash I realized that I had been transported into the greatest acid Western never made. I was not deluded; I knew I was inside the fantasy of an imagined film, rather than some parallel reality, but I was still inside it as much as I was enjoying it. The celluloid satisfaction continued unabated for a few minutes, as I tarried in the grainy sunlight there with the yucca match cuts and the law on my ass and the long distant moan of the harp.

I hadn’t thought about that afternoon for years until I saw the Dirtwire video, which in its own mesmerizing, artificial, and kitschy way both stirred up and satisfied anew the now moldy counterculture fever dream of the acid Western. I marvelled that AI was capable of such a psychoactive feat, in the right hands anyway, and directed toward the right, or rightly addled, mind. But the more I think about it, the more that minor key melody snakes its foreboding way through my long-haired drifter soul, whose dreams now appear to have been penetrated and algorithmically hollowed out by the latest and greatest engine of the robber barons, the most powerful iron horse yet to scream down the rails of progress, careening towards the most nameless tomorrow of all.

Also…

(•) I haven’t been on a podcast for awhile, but Brian James lured me onto Howl in the Wilderness the other day to talk about Gen X, media culture, and how much fun the 1990s were. I have always felt very much a part of the post-Boomer generation, and have thought a lot about the specific changes we have undergone, a shift that I call, for reasons I explain in the podcast, “the analog sunset.” While generational conversations between middle-aged dudes always threaten to veer into “kids today” gripes, I think we generally avoided the trap.

What saved us perhaps was adhering to the “just don’t know” mind incarnated by my pal Grover in the image above. Brian was very taken with this figurine, which features Sesame Street’s most everyman Muppet facing the big fat zero at the heart of it all, and responding with honest bemusement. So Brian tracked down his own Grover and, in a very Gen X gesture of sacred slackerdom, added it to his plant medicine altar.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. For now, I dodge the stress of the hamster wheel by not offering paid subscriptions, although I strongly encourage you to forward away and to grab that free subscription because I love those slowly rising numbers. Plus you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.