from The Occult World (Routledge, 2014)

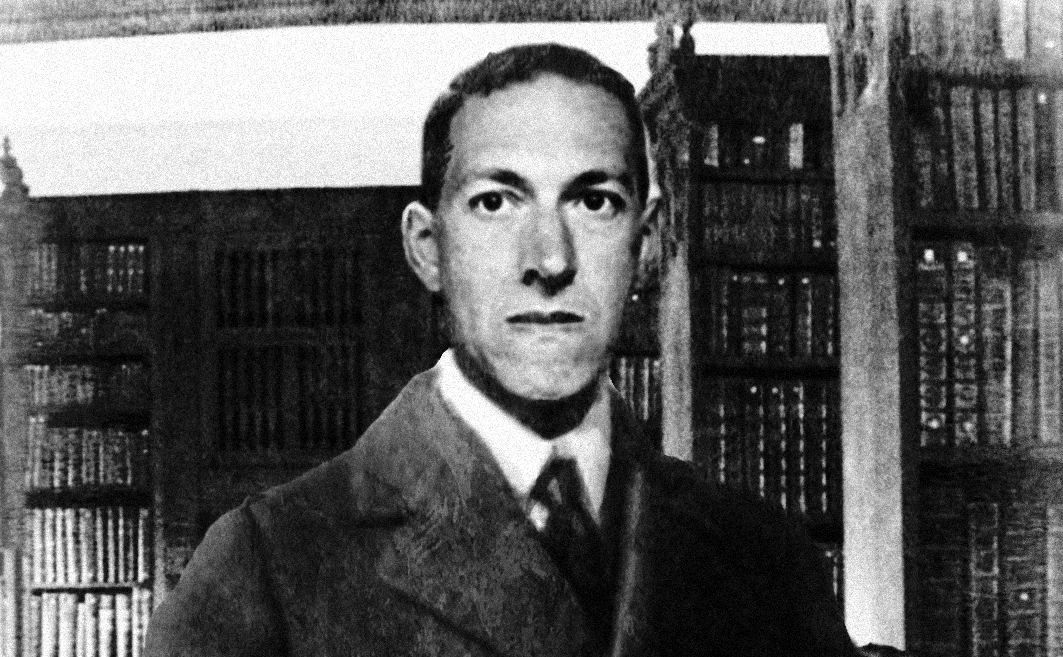

H.P. Lovecraft was an American writer principally known for his weird fiction, a British and American sub-genre of speculative narrative that he helped both characterize and, as a critic, define. In his tales, Lovecraft blended elements of fantasy, horror, and science fiction into a strikingly original, infectious, and highly influential narrative universe. Lovecraft’s weird fiction is characterized by a fascination with occult grimoires and forbidden knowledge; a pantheon of bizarre extraterrestrial pseudo-gods who are essentially inimical to human life; a nostalgic attachment to the history and landscape of New England; and a heavily racialized concern with human degeneration and atavistic cults. In contrast to the implicit supernaturalism of ghost stories or the gothic tale, the metaphysical background of Lovecraft’s stories is a “cosmic indifferentism” rooted in the nihilistic and atheist materialism that Lovecraft professed at great length in his fascinating letters. This lifelong philosophical stance led Lovecraft to embrace the disillusioning powers of science, but also to pessimistically anticipate science’s ultimate evisceration of human cultural norms and comforts. His weird tales were imaginative diversions from this nihilism, but their horror reflected it as well. Lovecraft’s literary vision was also amplified by the vivid, often nightmarish, and intensely detailed dreams he experienced throughout his life. A crucial influence on his fiction, Lovecraft’s dreaming can be seen as a phantasmic supplement to the reductive naturalism of his intellectual outlook, lending his work an uncanny dynamism that helps explain its continued power to stimulate thought, imagination, and cultural creation.

Lovecraft was born in Providence, Rhode Island to a privileged and pedigreed New England family. For the rest of his life, he would remain under the spell of the manners, aesthetics, and class attitudes he associated with that heritage. Lovecraft’s father was committed to an insane asylum when the boy was less than three years old, most likely due to tertiary syphilis. Lovecraft grew up an only child in a household dominated by doting and indulgent women; alongside the pampering, he began to experience recurrent nightmares peopled by terrifying “night-gaunts.” When his beloved maternal grandfather died in 1904, the family fell on hard times; for the rest of Lovecraft’s life, with some exceptions, and partly due to his own hyper-sensitivity, he lived on the margins of poverty. Through a precocious intellect, Lovecraft dropped out of high school, falling into a period of intense social isolation that was relieved when he discovered the world of amateur journalism. In 1919, his psychologically unstable mother was also committed to an asylum. Shortly after her death two years later, Lovecraft met and eventually married Sonia Greene, an older Jewish woman and the only obvious love interest in Lovecraft’s rather asexual life. His relationship with Greene brought him to New York City for a few years but the marriage did not last long and Lovecraft returned to his beloved Providence, where he lived with his aunts. A teetotaler with a simple diet, he generally hewed to an ascetic existence, but he traveled some and maintained an extraordinarily voluminous and thoughtful correspondence with many friends and peers, including amateur journalists and weird fiction writers like Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, and other members of the “Lovecraft circle.” He died of intestinal cancer in 1937 at the age of 46.

Publishing his fiction chiefly in Weird Tales, Lovecraft was not widely read during his life, and his archaisms and other stylistic mannerisms turned off some pulp fans just as they continue to challenge readers today. Drawing inspiration from earlier masters of the weird tale like Poe, Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, and William Hope Hodgson, Lovecraft wrote scores of striking short stories and novellas that, for all their inconsistency and even contradiction, are held together by an enigmatic intertextual web that includes the invented New England geography of “Arkham country”; grimoire titles like the Pnakotic Manuscripts and the dread Necronomicon; a cosmology of multiple dimensions and recurrent Dreamlands; and a pantheon of barbarously-named beings like Cthulhu and Azathoth, who are generally known as the “Great Old Ones” or the “Outer Gods.” During his lifetime, Lovecraft encouraged members of his literary circle to contribute stories to what Lovecraft informally called, after one of his principle beings, his Yog-Sothery. Following Lovecraft’s death, August Derleth, who founded Arkham Horror largely to publish the work of his friend and mentor, coined the term “Cthulhu Mythos” to describe this shared fictional universe, which Derleth and others in the Circle continued to elaborate and extend. Over time, thousands of amateur and professional writers across the globe would come to do the same, as well as numerous filmmakers, illustrators, sculptors, game and toy designers, and comic-book artists. Lovecraft’s work has also spawned a thriving and appropriately arcane domain of Lovecraft scholarship, and has even been addressed by philosophers like Graham Harman and Gilles Deleuze. Arguably the most unusual response to Lovecraft’s work, however, has come from occultists, who have made his work perhaps the single most significant fictional inspiration for contemporary magical theory and practice, particularly within chaos magic and various left-hand and Thelemic currents.

Lovecraft’s Representation of the Occult

To illuminate Lovecraft’s fictional transformation of the occult, it is helpful to conceptually distinguish two streams of lore and practice of the Western magical arts. On the one hand, there is an elite stream of learned magic associated with literacy, arcane knowledge, and to some degree fraternal orders—an “esoteric” cultural orientation that includes medieval monks as well as, for example, Victorian Freemasons enthralled with Egyptian mysteries. On the other hand, there is the vast, amorphous, and often highly localized body of folklore, seasonal ritual, herbcraft, hexing, and healing techniques associated with rural life or communities with low degrees of social status and formal education. This “popular” magical culture has in many ways left scant traces in the historical record, which in turn has allowed scholars and occultists alike to invent sometimes highly speculative accounts of its characteristics—accounts that themselves sometimes become part of the occultist milieu.

Lovecraft’s most extended engagement with the Western esoteric stream occurs in his short novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, written in 1927 but not published until after his death. Relatively free of Yog-Sothery, the work also stands as Lovecraft’s most thorough treatment of his recurrent theme of ancestral possession, as well as a monument to the man’s love for the architecture and history of Providence. In the story, we learn of the young Charles Ward’s obsession with and eventual resurrection of his forefather Joseph Curwen, an 18th-century necromancer, alchemist and psychopathic murderer who discovered the art of using “essential Saltes” to re-animate dead shades. Though not as scholarly as many of Lovecraft’s heroes and villains, Curwen is a man of education and high status. At one point we are given a brief catalog of Curwen’s library, which includes books of occult and natural philosophy by Paracelsus, Van Helmont, Trithemius, and Robert Boyle, as well as classic esoteric texts like the Zohar and the Hermetica. Lovecraft’s regular inclusion of rare books, as well as the narrative device of a young researcher studying his or his locality’s past, helps set up his central concern with the ironic dialectics of forbidden knowledge. Charles Dexter Ward, for example, is killed by the object of his genealogical research. But perhaps the most succinct expression of this dialectic lies in the game play of Chaosium’s highly successful Call of Cthulhu RPG franchise: the more a character learns about the Mythos, the closer they come to going insane.

In his catalogs of grimoires, Lovecraft usually includes a copy of one of his most famous fictional inventions: the dreaded Necronomicon, a book by “the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred” concerning the lore and invocation of the Old Ones. By including the Necronomicon alongside esoteric books, Lovecraft helped heed his own admonition that, for a weird story to be effective, it must be devised “with all the care and verisimilitude of an actual hoax.” Some readers, then and now, believed that The Necronomicon was an actual text, and Lovecraft himself wrote a brief pseudo-history of the book, which we learn was translated into Greek by Theodorus Philetas, into Latin by Olaus Wurmius, and later into an unpublished, fragmentary English edition by the Renaissance mage John Dee. Despite his playful references to esoteric literature, however, Lovecraft did not have enough respect for the occult to become a scholar of it; in the mid-1920s, with his Yog Sothery already underway, Lovecraft admitted that his knowledge of the history of magic was largely restricted to the Encyclopedia Britannica. That said, Lovecraft did recognize that learned magic is in part characterized by the intertextual web of referentiality that grows between largely inaccessible and cryptically entitled books, a web that itself can be imaginatively extended. Alongside the Necronomicon, whose name came to Lovecraft in a dream, Lovecraft’s Mythos stories include references to many other invented grimoires, like the Book of Eibon and De Veris Mysteriis, both of which, in a second-order instantiation of the intertextual web, were concocted by other writers in Lovecraft’s circle.

Alongside Lovecraft’s inventive engagement with the esoteric occultism, he also wrote obsessively about primitive or atavistic magical cults, often composed of rural, marginal or impoverished communities, in the West or abroad. One important scholarly source for this vision was Margaret Murray’s 1921 book The Witch-Cult in Europe, which also went on to play an important role in the establishment of modern Wicca. Controversially, Murray argued that beneath the violent ecclesiastical machinery of the European witch trials lay the remnants of an actual pre-Christian fertility religion. For Lovecraft, who grew up sixty-five miles from the home of the Salem witch trials, Murray’s vision of the ancient witch-cult—which included accusations of child sacrifice—gave him license to develop the theme of an archaic and savage magical religion that continues to persist in modern times. Inspired as well by the fiction of Arthur Machen, who linked witchcraft with the fairy lore of the “little people,” Lovecraft also associated the witch-cult with pre-Aryan or “Mongoloid” peoples, which he readily combined with his racist concerns with degeneracy and immigrant populations. Examples of such cults in his fiction include the mixed-blood voodoo sect in “Call of Cthulhu” and the Yezidi devil-worshippers in “The Horror at Red Hook,” a New York-inspired tale not usually classed with the Mythos.

Though Lovecraft separately re-imagined these two streams of elite and popular magic, he achieved his unique vision of the occult in part by promiscuously commingling them. In “The Dunwich Horror,” for example, Wilber Whateley and his isolated rural family are declared to be of degenerate stock, and practice strange rituals on the sinister Sentinel Hill, topped by an altar-like stone and featuring caches of ancient, possibly Indian bones. At the same time, Whateley needs to get the words of one his invocations exactly right, so he travels to Miskatonic University in order to compare their Latin edition of the Necronomicon to the fragmented Dee version he possesses. In Lovecraft’s world, learned magic unleashes atavistic and prehistoric powers rather than hierarchies of angels or devils; as such, he is able to depict an ancient but vital left hand path that is free of Satanism or Christian demonology. On the other side of the coin, Lovecraft’s primitive cults, including the sort of exotic tribes that haunt the anthropological imaginary, are characterized by their ongoing relationship with the ultimate forces of the cosmos. Lovecraft first makes this ground-breaking move in his famous 1928 story “The Call of Cthulhu,” wherein Lovecraft reframes the primitive gods worshipped by voodou initiates and remote “Eskimo wizards” as extraterrestrial or inter-dimensional beings.

Later entering popular culture as Erich von Daniken’s “ancient astronaut” theory, Lovecraft’s atavistic science-fictional cosmology allowed his fictions to undermine the progressive Enlightenment view of religious history popularized by Tylor and Frazer while still upholding the scientific course of civilization. The savage mysteries that animate the most primitive human cults are no longer the result of ignorant and neurosis but instead encode actual truths about the cosmos, including powerful extraterrestrial entities and dimensions of reality—like Einsteinean space-time and the non-Euclidean geometry used to describe it—that early 20th century astrophysics is only beginning to understand. Lovecraft’s most explicit intertwining of the witch-cult and weird science occurs in the 1932 story “The Dreams of the Witch-House.” At first, the demonic characters that the folklorist Walter Gilman glimpses in his nightmares and in the oddly shaped corners of his room seem unusually traditional for Lovecraft: the evil witch crone Keziah Mason, her evident familiar spirit, and a “Black Man” who is possibly Lovecraft’s most unambiguously Satanic figure. But Gilman is also a student of quantum physics and non-Euclidian geometry, and his nightmares also seem to take place within an “indescribably angled” hyperspace. Within these seething abysses, Gilman regularly encounters a small polyhedron and a mass of “prolately spheroidal bubbles” that turn out in the end to be none other than Keziah and her familiar. Lovecraft is thus able to “save the appearances” of supernatural folklore by superimposing them onto an expansively naturalistic if no less disturbing cosmos.

The Occultist Reception of Lovecraft

From the time of Lovecraft’s death, his name and work was kept alive by August Derleth and other members of the Lovecraft circle. But a mass Lovecraft revival would have to wait until the 1960s, when his stories, along with work by his friends Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith and other weird fiction writers, starting appearing in affordable paperbacks designed to exploit the market for adult fantasy opened up by Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, as well as, arguably, the growing use of cannabis and LSD. Inevitably, the exotic aura of dark magic that suffuses Lovecraft and the best writers in his circle fed into the “occultic milieu” that characterized much countercultural spirituality. The first explicitly occult appropriation of Lovecraft’s fiction can be traced to the British magician Kenneth Grant, one of the most vivid and controversial figures to emerge from the Thelemic current begun by Aleister Crowley, and the renegade head of the New Isis Lodge and the Typhonian Ordo Templi Orientis. Writing for Man, Myth and Magic in 1970, and two years later in his book The Magical Revival, Grant argued that, through his remarkable dream life, Lovecraft was linked to actual traditions of ancient and contemporary magic; in this view, The Necronomicon is a “real” book tucked away in the akashic records that Lovecraft’s waking mind was too hidebound and timid to accept. Grant was particularly keen on lining up curious similarities between names and other elements of Thelemic and Lovecraftian lore, like Yog-Sothoth and Crowley’s Sut-Thoth. In all this, Grant’s own degree of irony or diabolic playfulness is, as ever, hard to assess. Given his florid imagination and parsimonious use of scholarship, Grant’s texts—which include ruminations on Bela Lugosi—already scramble the borderlines between occult originality and fiction.

The year 1972 also saw the publication of Anton LaVey’s The Satanic Rituals, a companion text to the Church of Satan leader’s popular The Satanic Bible. The book includes two Lovecraftian rites written by LaVey’s deputy Michael Aquino, the “Ceremony of the Angles” and “The Call to Cthulhu.” In his introduction, Aquino legitimizes the occult appropriation of Lovecraft along much less supernaturalist lines than Grant, emphasizing instead Lovecraft’s own amoral philosophy and the subjective, archetypal, and possibly prophetic power of fantasy. This argument accorded with the language of “psychodrama” that LaVey himself offered as non-supernatural explanations for the transformative power of blasphemous ritual. As a pragmatic corollary to this constructionist view, Aquino developed a meaningless ritual language for his rituals, a “Yuggothic tongue” based on the alien speech Lovecraft provides in “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Whisperer in the Dark.” The efficacy of such guttural and semantically empty speech is also described by Grant in his discussion of the Cult of Barbarous Names.

Within the Church of Satan, LaVey founded an informal “Order of the Trapezoid” whose name was inspired in part by Lovecraft’s story “The Haunter of the Dark,” which features a “shining trapezohedron” used by an extinct cult called the Church of Starry Wisdom. The Order of the Trapezoid would later become the supreme executive body of Aquino’s Church of Set, where the Lovecraftian current was interpreted in part as a force of apocalyptic subjectivity. Other notable Lovecraftian orders over the decades have included the Lovecraftian Coven, founded by Michael Bertiaux, a practitioner of “Gnostic Voudon;” Cincinatti’s Bate Cabal; and The Esoteric Order of Dagon, a Thelema- and Typhonian-inspired sect founded by Steven Greenwood, who in the 1960s became magically identified with Lovecraft’s fictional hero Randolph Carter. Lovecraftian magic has also became an important, almost signal leitmotif for chaos magicians, whose “postmodern” (and largely left-hand) approach to the contingency of traditional occult systems is resonantly affirmed by the adaptation of a fictional and profoundly anti-humanist cosmology that has the additional feature of being concocted by a philosophical nihilist.

Having achieved an intertextual virtual reality, The Necronomicon eventually manifested in the physical world of publications as well. In 1980, Avon Books—who also published LaVey—released a version of Alhazred’s book by the pseudonymous “Simon.” Emerging from Herman Slater’s New York occult bookstore Magickal Childe, Simon’s text, which has never gone out of print, is a practical grimoire featuring a fictional frame and rituals that mash up Sumerian lore and European Goetic magic. Less popular was the Necronomicon published by George Hay, a hodge-podge that includes literary essays, fabricated translations of John Dee, and an introduction by Colin Wilson. The most faithfully Lovecraftian version of the Necronomicon was arguably written by Donald Tyson and published by Llewellyn in 2004. Tyson has since become a one-man font of Lovecraftiana, including spell books, a Tarot deck, and an intelligent literary biography that combines sober critical analysis with a Jungian and paranormal twist on Grant’s strategies of legitimization.

Regardless of such strategies, the occult appropriation of Lovecraft can be traced in part to the intertextual and metafictional dynamics of the texts themselves. The central theme that Lovecraft critic Donald Burleson identifies as “oneiric objectivism” is itself the central vehicle for occultist legitimization; from this perspective, occultists impose a second-order level of objective dreaming to the textual circuit that Lovecraft himself established between his actual dreams and his fictional worlds. Occultists could certainly be accused of turning Lovecraft the writer into something he’s not and would moreover abhor. The irony, however, is that this supernaturalist overwriting of the author’s materialism is itself inscribed in Lovecraft’s fiction, which—unlike the detective fiction it occasionally resembles—usually encourages the reader to piece together the horrifying cosmic scenario long before the bookish and blinkered protagonists put the pieces together. In a larger sense, occultists might simply be seen as culture makers who have, like thousands of writers, accepted Lovecraft’s invitation to play the game of imaginatively co-creating the Mythos. In the occultist version of the game, however, players risk the element of verisimilitude that Lovecraft himself saw was a key element of the “hoax.” And like the empty networks of referentiality that undergird the substance of occult literature, such games may have a life of their own.

***

References

Burleson, Donald R. (1991) “On Lovecraft’s Themes: Touching the Glass,” in S.T. Joshi (ed.), An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H. P. Lovecraft, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press: Rutherford, New Jersey.

Davies, Owen (2010), Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Davis, Erik (1995), “Calling Cthulhu: H.P. Lovecraft’s Magickal Realism,” Gnosis, no. 37, pp. 56-64.

Joshi, S.T. (1982), A Subtler Magick: the Writings and Philosophy of H.P. Lovecraft, Wildside Press: Gillette, New Jersey.

Joshi, S.T. (2001), A Dreamer & A Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time, Liverpool University Press: Liverpool.

Lachman, Gary (2001), Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius, Sidgwick & Jackson: London.

Price, Robert (1985), “H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos,” Crypt of Cthulhu, no. 35, p. 9.

Tyson, Donald (2010), The Dream World of H.P. Lovecraft, Llewellyn: Woodbury, MN.

Waugh, Robert H. (1994), “Dr. Margaret Murray and H.P. Lovecraft: The Witch-Cult in New England,” Lovecraft Studies, no. 31, pp. 2-10.

Waugh, Robert H. (2006), The Monster in the Mirror: Looking at H.P. Lovecraft, Hippocampus Press: New York.