The Philosophy of the Matrix

The most curious feature of Warner Bros’ official Matrix website is not the handful of jaw-dropping Animatrix clips, but the collection of high-quality philosophical essays by heavy hitters like Hubert Dreyfus, Colin McGinn and the cognitive science superstar David Chalmers. These essays, which hash out Descartes, Mahayana Buddhism and the proverbial “brain in the vat” problem, are all the evidence you need that the Wachowski brothers’ original 1999 film has vaulted into that curious category of Big Think mainstream sci-fi films — and that they want the “kickass” sequel to extend the beard-pulling.

No one is surprised when filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky or Chris Marker or Stanley Kubrick use future shtick for metaphysical purposes, but it’s another thing for Hollywood action fare — designed to reap big bucks from the popcorn crowd — to create a space of inquiry into philosophical, political and spiritual questions, however “comic book” the frame. Movies like Blade Runner, Robocop, They Live, Minority Report, and the Alien and Terminator flicks have managed, sometimes through no fault of their own, to edge toward the profound. But the Wachowski brothers made it to the top of this heap with the most lucrative sci-fi action empire to feed the questioning, and questing, mind.

Now, with demiurgic ambitions matched only by Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson, the brothers have unveiled the next chapter of their live-action post-apocalyptic anime franchise. As a movie, The Matrix Reloaded has some serious flaws: Many sequences drag, the pacing is jangled and there are far too many dreadlocks. But I have no problems with the pretentious, concept-heavy dialogue. Some reviewers imply that this metaphysical kitsch detracts from the fun; for some of us, it is the fun. At one point in the new film Neo returns to the Matrix and wanders through a street market full of religious junk: chintzy Mother Maries, head-shop Shiva posters, and blinking Jesus plaques. This is the pop carnival of souls where the Matrix films rightly take their place — the flea market of genre movies and rumors of God that, for many these days, is the only portal left into the meaning of it all. In the words of Philip K. Dick, whose spirit (but not tone) hangs over the Matrix, “The symbols of the divine initially show up at the trash stratum.”

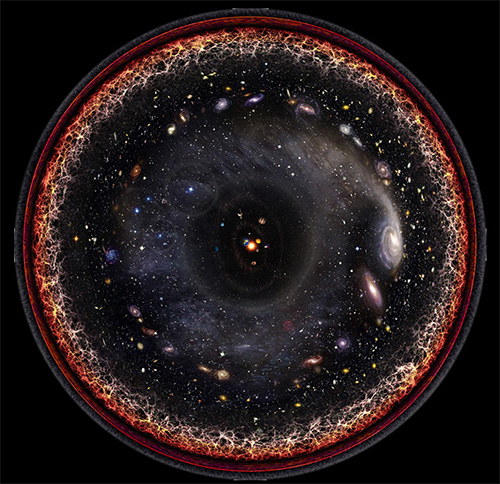

The Wachowski brothers may be too self-conscious about their divine trash, but in the end that’s what feels true, or at least contemporary, about the Matrix films: their excessive self-consciousness about selves and consciousness. The original Matrix hit home by digitally remastering a time-honored (because always timely) conundrum: How do I know that reality is not a total illusion? Though this question gives off a cheesy adolescent fizz, it’s more than a stoned gedanken experiment, like Pinto’s speculation in Animal House that our entire universe might be an atom in some all-being’s fingernail. The question lies at the heart, at least, of Western epistemology, with Descartes.

In order to escape medieval authority and embrace the proud autonomy of the rational “I,” Descartes battled a “demon of doubt” that undermined everything it could, including the reality of the world before the philosopher’s eyes. Descartes’ skepticism, with its sci-fi scenarios of false worlds and automatons disguised as human beings, initiated a revolution in thinking that, in some sense, ultimately leads to the universal machines that sit on our particular desks. The Matrix, with its mathematicized objects and Cartesian coordinates, is really Descartes’ storyboard.

Descartes dreamed great dreams as well — like the angel who appeared to him one September night, proclaiming, “The conquest of nature is to be achieved through measure and number.” Most of us have such veridical dreams on occasion, when visionary Technicolor truths burst through the usual REM murk. At the very least, the power of these dreams reminds us that the “false reality” problem strikes a far deeper note than skepticism alone can sound. Millennia ago, human beings had to face the fact that our minds regularly pass through realms very different from the seemingly solid world, however we choose to interpret them. In other words, the Matrix problem arises from our wetware’s capacity, through dreams, drugs or trance, to boot up radically different worlds of consciousness. That’s why Descartes’ skepticism still resonates with cultural narratives as different as Hindu folklore or Gnostic myth or the Taoist Zhuangzi’s famous quip (intended with more comedy than I think we now hear): “How do I know I am a man dreaming he was a butterfly, and not a butterfly dreaming he is a man?”

The Matrix problem becomes particularly unavoidable in the age of virtual technologies, which constantly narrate their own totalizing dreams of “world-building” and “experience design.” Of course, media have long sought to create immersive spaces of fictional reality: Baroque cathedrals, 19th century panoramas, even, perhaps, the Paleolithic caves of Lascaux or Altamira. Today, the accelerating perceptual technologies of media are on a collision course with cognitive science and its understanding of how the human nervous system produces the real-time matrix we take for ordinary space-time. So we should not be surprised at the massive popularity of a Hollywood slug-fest where dream and reality and virtual technology enfold one another. Not only does the film mythologize the game-world aspirations of so much popular media, it stimulates the corresponding desire to crack through — and remake — the construct.

What was particularly savvy about the Wachowskis’ comic-book movie was that its mirror-shade cool reflected any number of readings — Marxist, Lacanian, utterly stoned. Perhaps most surprising, and influential, was its use of religious symbols and viewpoints. Most viewers picked up on the Christian elements of the first film, which center on Neo’s role as a savior figure, but the deep frame of both movies is a more esoteric pop stew of Gnostic and Buddhist ideas. The Gnostics of antiquity transformed the analogy of Plato’s cave into a full-blown and harrowing cosmology: We are strangers trapped in a strange land, they argued, immortal sparks slumbering in a material cosmos fashioned by an evil or ignorant demiurge and his nefarious archons. The Buddhist analysis is less personalistic: We are stuck on the delusive merry-go-round of samsara, an almost mechanical system of causes and conditions that fools us into believing the self and the world are substantially real. In both cases, we step toward the light not through grace or the remission of sins, but through the direct awakening of insight into our condition. Neo must swallow his pill and take the ride himself.

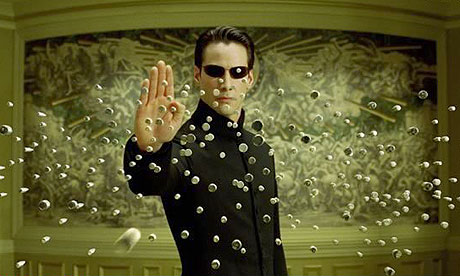

Opening in theaters on Buddha’s birthday, The Matrix Reloaded clearly places itself in a crypto-religious landscape. There’s a ship called the Logos, characters like Seraph and Persephone and Neo’s hushed worship by the multiculti masses of Zion. Neo’s mystic powers are growing as well: His “second sight,” which allows him to see into the underlying code inside the Matrix, lets him read energy bodies and, in a remarkable fusion of Christ myth and shamanism, resurrect Trinity by removing a bullet embedded in her body. But The Matrix Reloaded would have been lame if it had simply followed its Gnostic bodhisattva superhero around as he kicked ass in Jesuit robes. Instead, to keep the cognitive sparkle, the Wachowskis altered the conceptual maps of the two worlds that Neo moves through: Zion and the Matrix.

In the first film, these two worlds had the virtue of simplicity: We slipped neatly between the world of the Matrix, with its single nefarious agenda, and the revolutionary messianic world of Morpheus’ ship, the Nebuchadnezzar. But The Matrix Reloaded complicates these two worlds. Before the Nebuchadnezzar even arrives at Zion, we realize that Morpheus — previously the hierophantic voice of truth — may simply be crazy, an irrational demagogue, a renegade believer. Meanwhile, the Matrix grows far more complex. In the first film we sensed a unity of purpose and design behind the agents and their urban landscape, but now we confront a Babel of programs: rogue self-replicating agents, the power-mad Merovingian, the intuitive Oracle, all competing in an open-ended nest of potentially infinite regress. As the Oracle admits to Neo, it’s a pickle: There’s no way for him to know what’s going on or whom to believe.

The Matrix comes to resemble the multifarious world of shamanism rather than the black-and-white world of the Christian afterlife. Neo, the otherworldly voyager, encounters a wide variety of beings, each with his or her own contradictory raps and agendas, and none entirely trustworthy. The architecture of the Matrix has also become pickled, an Escheresque Swiss cheese of transdimensional hallways and quantum portals. If The Matrix was all about screens and mirror shades, The Matrix Reloaded is all about keys and doors. The keys are codes of course, the language of encryption, but they are also the keys of magicians navigating through angel-space. And the portals we keep passing through remind us that the action lies between the worlds, as the conventional cartography of the Matrix melts into the metamorphic palaces of dream.

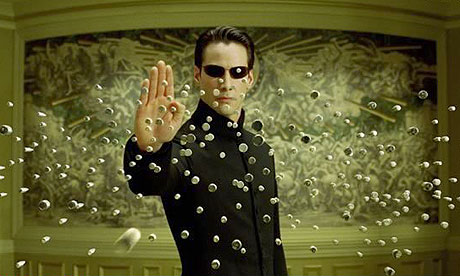

After all, however much you resonate with the cabalistic or Marxist metaphors, the Matrix most resembles the shifting virtual worlds that our brain conjures nightly. The first glimpse that The Matrix Reloaded gives us of the Matrix — when Trinity falls to her apparent demise beneath a rain of bullets — turns out to be a recurrent dream in Neo’s head. What makes this dream a nightmare is not just Trinity’s death, but Neo’s own inability to intervene in the scenario. We’ve all gotten caught in these hypnagogic snares, where you face some horror but cannot move — encased, as it were, in the amber of dream time. What we want in these moments is the secret wish whose fulfillment animates these films: the desire to awaken inside the phantom world and wrest control from the dream machine.

On this level of psychic control, both Matrix films can be read as Castaneda-esque instruction manuals for lucid dreamers. As the first film suggests, the simple knowledge that one is dreaming is not usually enough to exert control on the illusory world; instead, one achieves full creative action only after a lot of training in the dreaming dojo. The first thing that a lot of dreamers do when they first go lucid is also one of the first visual pleasures The Matrix Reloaded gives us: flight. Neo’s bat-winged cruise through the moonstruck heavens is not just a Superman reference, but also a specific invocation of our own dream experience. This is what people don’t understand about the Wachowskis’ special effects, many of which revolve around virtual camera moves impossible to generate in the real world. Remember the subconscious equation of film: I am the camera. When the Wachowskis propel their camera faster than a speeding bullet, when it swoops and dives with angelic grace or whips through a frozen moment of space-time — these novel perceptions strike us at first as virtual experiences, familiar only through dream time or trance.

Of course, the novelty of these effects wears off fast, and we soon assimilate the technique as mere technological rhetoric. “Bullet Time” sells beer now; we are not impressed. Our rapidly jaded eyes drive the arms race of special effects, a race that suggests that we will not be satisfied until we somehow break through and manipulate space itself — a pleasure now increasingly available through computer games, like the Wachowskis’ own Enter the Matrix. As in lucid dreams, the question is all about control, a control that necessarily implies a certain technical disenchantment. We can control our dreams when we recognize they are merely dreams, just as we can create the “magic” of FX only with the total mathematicization of space-time and the images of human bodies.

The Matrix films are not neo-Luddite propaganda; the Wachowskis recognize that technology accompanies all our dreams. Early in the film, an insomniac Neo wanders through the depths of Zion as Councilor Hamann draws his attention to an irony only implicit in the first film: The good guys also depend utterly on machines. In their stilted chat, Neo differentiates between the Matrix and Zion’s technological infrastructure, a steam-punk space of Tesla-coil arc lights and corroded Modern Times gears that looks back to the organic textures of the last century. Neo implies that Zion is free because humans have control. But this 19th century romance only raises the question Hamann asks him: “What is control?”

This question is not just the nut of the movie. It is the central koan of our cybernetic civilization and its ever more intricate symbiosis with algorithms, control systems and the kind of self-replicating bots suggested by Agent Smith. All the representatives of the Matrix, even the Oracle, continually suggest that conscious human agency is not what it’s cracked up to be. During his first balletic bash with Neo, Smith, though now apparently a “free agent” like Neo, insists that everything is determined by its purpose. He does not use the term as Morpheus later does, to suggest destiny or a higher calling. Instead, he means a techno-Darwinian logic, a programmed calculus of success. His is the voice of the evolutionary psychologist, who delights in deconstructing our most spirited social actions in terms of the base advantage they confer. This is also the perspective of the Merovingian, who comes off as a curious hybrid between Jesus Christ Superstar‘s Herod and Pilate. With the aphrodisiac piece of pie he feeds a future fuck-bunny, the Merovingian raises the distinct glandular possibility that “decision” is simply the story the brain tells itself about the neural cascades of electrochemical reactions that underlie behavior. Code rules: Despite appearances, we are out of control.

As mythographers, the Wachowskis realize that the cybernetic problem of control reboots the hoary old struggle between freedom and fate. Morpheus, for example, is convinced that everything is proceeding according to cosmic plan, but his increasingly tedious speechifying about destiny and prophecy weirdly mirrors Agent Smith’s grim talk of mechanical purpose. What, then, is the proper rejoinder to determinism? The Oracle tells Neo that “You are here to understand why you made the choice, not to make the choice.” I take this to mean that, to an awakened one, events and decisions have always already occurred, but that understanding and compassion can still dissolve their karmic hold.

OK, enough already. It’s silly to squeeze too many meanings from a cyber-chopsocky flick; as in the anime tradition the Wachowskis draw from, metaphysical puzzles are more for atmosphere than answers. I won’t even get into Neo’s final chat with the Architect, although I suspect that all the talk of anomalies and contingent affirmations won’t really add up in the end. But adding up is not really the point (unless you are talking about adding up the merchandise sold to fans who want to spend as much time as possible in the Wachowskis’ endlessly nested construct). Like the overly complex plots of film noir, which ultimately serve only to increase the vibe of claustrophobic paranoia, The Matrix Reloaded‘s fractured chatter is in service of an old Gnostic hunch: There is a crack in the cosmic machine, and we are the crack.

As I left the theater after watching the new film, I was handed a slick little flier. “Take the Red Pill,” it said. “Join the Resistance.” At first I thought it was a Christian tract, but it was Not in Our Name’s clever attempt at a wake-up call for a very sleepy nation. Here are the truths the tract’s authors offered: slaughtered Iraqis, Orwellian homeland security, deportations and military tribunals, endless war and repression. But they also saw a light at the end of the rabbit hole. “Another world is possible and we pledge to make it real,” they said. “Join us.” They listed some numbers, and I impulsively looked around for the nearest public phone, as if I were Clark Kent, or Neo trying to slip back out of the Matrix. I didn’t see one. They’re not easy to find these days.