From divinity to programming

He has quoted scripture before crowds of hackers. He glides from notions of devotion and divinity to the nuts and bolts of evolutionary programming. And his progeny is just about everywhere on the Web. Larry Wall, a linguist and self-effacing polymath, is the creator of the popular and ubiquitous Perl programming language. (Perl stands for “Practical Extraction and Report Language” or, if Wall is in the mood, “Pathologically Eclectic Rubbish Lister.”) Created over ten years ago with contributions and critiques of volunteer hackers, Perl is widely considered the “duct-tape” that holds the Internet together. It’s used for a gigantic array of tasks — at Yahoo!, a “grim reaper” written in Perl crawls through links to see if they’re still active, while others use it to create HTML pages on the fly.

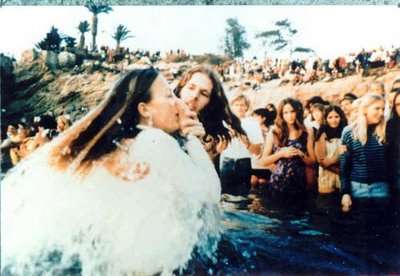

Perl isn’t Wall’s only passion. Wall is also a serious evangelical Christian, a member (and webmaster) of the New Life Church’s Cupertino Church of the Nazarene. He’s one of the few overtly religious figures in the pantheon of programmers, For him, language, code, and faith are — in a Perl-like mix — glued together.

Wall is the son and grandson of preachers, which means his Christianity is bred to the bone. Like other denominations that descend from John Wesley, the 18th-century founder of Methodism, Wall’s church embraces the idea of entire sanctification: an act of God can cleanse the human heart from original sin and fill the person with the desire to serve God and humankind — as Jesus proclaimed, “He who wishes to be greatest among you must become servant of all.”

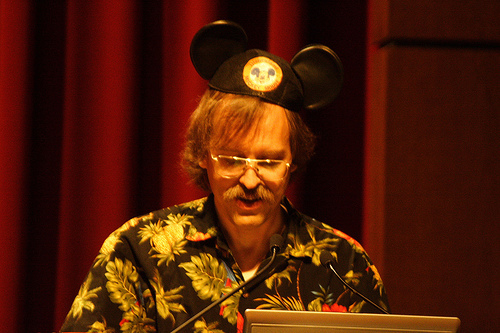

Wall is driven to build bridges between seemingly contrary worldviews, and his curious speeches — which reference everything from Richard Feynman to Bilbo Baggins — are the work of a man who thinks like he hacks (or vice versa). Wall’s talks also demonstrate his love of goofy noise. During the following phone interview, the conversation was occasionally interrupted by various prerecorded bells, whistles, and hallelujah choruses that someone or something had triggered inside Wall’s thoroughly wired home in Mountain View, California.

–Erik Davis

DAVIS:

Let’s say I am an alien anthropologist, studying computer languages, and I came across Perl. What’s going to grab me?

WALL:

One of the things that’s going to grab you as an anthropologist is the fact that there really is an anthropological story here. Most other computer languages are pretty sterile. They’re about technology. The difference with Perl is that I decided to create the culture at the same time as I was creating the language. My background is in both computers and linguistics… I put more ideas from linguistics into Perl than is typical in computer science.

DAVIS:

What are some of those ideas?

WALL:

The first and foremost is that natural [spoken] languages are not minimalistic. They are optimized for expressiveness rather than for simplicity. Right off the bat, that’s something that’s anathema to the typical computer scientist.

DAVIS:

‘Natural language’ implies a kind of messiness that allows for different users to arise, depending on different needs and circumstances…

WALL:

…Especially by virtue of the fact that many people have bent it to their own task. Since it was not designed by a single person, nobody enforces a single design philosophy on it. But by the same token, it’s rich enough that you can bend it to optimize for many different things. You can write poetry, you can write manuals, you can write recipes, you can write love letters. You can call plays in a football huddle, and you can babble.

DAVIS:

Where does ‘anthropology’ come in?

WALL:

Anthropology came from missionary training that my wife and I went through. It was with an outfit called the Summer Institute of Linguistics, which is affiliated with the Wycliffe Bible Translators. Their job is to go out and learn languages that have not been written down before, do a linguistic analysis of the language, come up with a writing system and then translate various things, including the Bible.

The biggest job they do during these summer training sessions is to break people out of their preconceptions. In all cultures, people identify their culture with universal truth in a way that confuses issues. Particularly Americans. The goal of a missionary is not to go out and build a little white church with a steeple out in the middle of nowhere. That’s a cultural thing, not a universal truth…

[With Perl], I was trying to encourage what I call diagonal thinking. Traditionally computer languages try to be as orthogonal as possible, meaning their features are at all at right angles to each other, metaphorically speaking. The problem with that is that people don’t solve problems that way. If I’m in one corner of a park and the restrooms are in the opposite corner of the park, I don’t walk due east and then due north. I go northeast — unless there’s a pond in the way or something.

I am told that when they built the University of California at Irvine, they did not put in any sidewalks the first year. Next year they came back and looked at where all the cow trails were in the grass and put the sidewalks there. Perl is designed the same way. It’s not just a random collection of features. It’s a bunch of features that look like a decent way to get from here to there. If you look at the diagram of an airline, it’s a network. Perl is a network of features… It’s more like glue than it is like Legos.

DAVIS:

And that’s reflected in the culture that has developed around Perl?

WALL:

I not only want Perl to be a good ‘glue’ language, I want Perl people to be good ‘glue’ people.

DAVIS:

What makes a good ‘glue’ person?

WALL:

Let me distinguish two different kinds of joiners. You have people who will join a movement and be totally gung-ho about it. That’s great. We need the cheerleaders.

But that’s merely a form of tribalism. What we also try to encourage are the kind of joiners who join many things. These people are like the intersection in a Venn diagram, who like to be at the intersection of two different tribes. In an actual tribal situation, these are the merchants, who go back and forth between tribes and actually produce an economy. In theological terms we call them peacemakers.

In terms of Perl language, these are the people who will not just sit there and write everything in Perl, but the people who will say: Perl is good for this part of the problem, and this other tool is good for that part of the problem, so let’s hook ’em together. They see Perl both from the inside and from the outside, just like a missionary. That takes a kind of humility, not only on the part of the person, but on the language. Perl does not want to make more of itself than it is. It’s willing to be the servant of other things.

DAVIS:

In one of your keynote speeches to the Perl community, you note that you’ve tried to model the Perl movement on another movement that you’re a member of: Christianity. How so?

WALL:

That’s more difficult to talk about, not because it’s embarrassing but because it works at a lower level in my psyche. I was born and bred to it at that level. I’ve always been on the church scene, and I’ve seen healthy churches and I’ve seen sick churches. I have a low-down feel for when things are being healthy and when they’re not, particularly in terms of the relationships between people…

A great deal of my theological thinking has been driven by the notion of trying to see truth from God’s viewpoint… I consider the theory of evolution to be by and large proven. And if that’s the case, then from God’s viewpoint, that has to be desirable. Why would God want to do it that way? Why would God want to use a seemingly random process to come up with more complex organisms?

Well, it’s a way of being creative. If you look at almost any game that people play, they are sitting there throwing dice. It’s also how artists work, particularly fiction writers. A good artist blends random-seeming factors with intentional factors into a pleasing pattern. To me that’s the mark of a better artist than somebody who can simply crank out a perfect picture of something you can see. Cameras can do that. But that’s still the view people have of how God has to operate. They still think there’s only one right way to make the universe, so this has to be it. Essentially that’s depriving God of free will — not to mention us!

DAVIS:

A lot of people who consider God and evolution fall on one side or the other, or just ignore the contradiction. You seem to be building bridges between them.

WALL:

It would be easy to compartmentalize, and many people have. Being a synthesist, that option was not open to me. I always have to consider everything. There are people who throw out various parts of their input in order to try to simplify, but I just don’t feel like I can do that. Beyond that, I feel like in a very particular way, God put me here to be an example of how you integrate seemingly contradictory things.

DAVIS:

Why did you not become a missionary?

WALL:

It turns out that I am allergic to a lot of things: seafood, wheat, eggs, tomatoes. People who are working out in the field can’t afford to be picky about what they are eating. But the training that I got was invaluable for what I was going to do later. I just didn’t know it at the time. A couple of years back I got email from somebody who was working at Wycliffe and didn’t know that I had been affiliated with them. He said, “By the way, we use Perl for all sorts of things here.” I wrote back to him and said, “You really made my day. No, you made my life.”

But in a sense I am still a missionary. I kind of consider myself an apostle to the hackers.

DAVIS:

The hacker community is full of very cantankerous and opinionated individuals. Have you gotten much grief for being so open about your Christian beliefs?

WALL:

I’ve had no difficulty with it. It’s been amazing. I think people recognize that I like them. I see God looking down on all these weird, cantankerous people, and kinda liking them, in an artistic fashion. And so I can’t help but sort of like them either, for all their foibles. There are certainly a bunch of what I would clearly label sinners out there. But they are real people, and they have real problems, and they just need real help…

The only thing that can be condemned is failure to improve. It’s a very simple thing, to…decide, it’s going to be different now. You only have to have faith the size of a mustard seed. Jesus is doing the heavy work.

DAVIS:

How did your theological and programming philosophies come to overlap?

WALL:

I don’t tend to modularize my thinking. When I was growing up, I had to stop reading science fiction for a number of years, because I couldn’t deal with it. I was growing up in a fundamentalist church, and I had a particular worldview, and typical science fiction is a fairly atheistic worldview. I really couldn’t deal with that at that age. What I recognized is that I was compartmentalizing, and rejected it. It shows that I was already thinking about those things then, trying to make it all work together.

DAVIS:

You have said that, “We need God, the ultimate in control, and we need evolution, the ultimate in chaos.” A lot of people are content with the evolution. What is missing from the universe of the selfish gene?

WALL:

Any notion of purpose. Any notion of morality. Any notion of obligation.

DAVIS:

Many hackers think in strictly evolutionary terms, which tends to hedge against or even deny the kind of “morality” and “purpose” you describe. Has the pervasiveness of that worldview resulted in some of the less seemly aspects of the software scene?

WALL:

The chief proponents of atheism in the 20th century were perhaps the communists. They produced a culture that was very coercive at some level. There are aspects of software culture that are very coercive. Certainly on the commercial end, there’s a great deal of coercion that everyone recognizes. But also on the opposite extreme. For the folks who believe that information should be free, or shared among all, it’s a communal thing. I view them as the people who want to gather all the farmers onto a collective. My take on giving away software is that this sort of thing should not be coerced. I much prefer the U.S. model, where if I want to help somebody out I can donate to them of my own free will, not at the point of a gun.

DAVIS:

You want to find a middle way between these very different collectivist extremes.

WALL:

Yes, I’m not into a hive mentality. What the extremists sort of want is this notion that we are all workers in this hive, and we all contribute, but we don’t have any individual rights — except the right to everything, whatever that means. The theological notion that we are each individually valuable in the sight of God puts a different viewpoint on what humans really want and how they should treat each other.

To me, the whole core of the Christian message is that God, who is this cosmic author, wrote himself into his own story, and proved himself to be more humble, and a better man than any of the rest of us. Anyone who aspires to be a cosmic artist, or a not so cosmic artist, really ought to be looking into the same system of doing things.

DAVIS:

Your role as the artist-honcho of the Perl movement involves both control and loss of control. What guides your hand?

WALL:

I definitely try to exercise as little control as possible. I am reminded of Tolkien in his preface to the Lord of the Rings, where he writes that he prefers manufactured history to allegory, because allegory is the purposeful domination of the author. Any good leader who is actually trying to encourage good sub-leadership will try to exercise as little power as possible. If I were a domineering sort of person, then people would not feel comfortable taking positions of leadership within the Perl community. The fact that I don’t abuse my power is what lets me keep my power.

DAVIS:

In one of your speeches you quote Jesus: “He who wishes to be greatest among you must become the servant of all.” You link that idea to the “onion” of the Perl community, where you are at the center but the real action is along the periphery…

WALL:

I can be up here in front of the Perl community and kind of be their demigod, and I can make jokes about getting a swelled head, and I don’t have to not be that kind of leader merely because I think that I have to be humble. That’s not what humility is. I think God put me here for a reason. I remember walking down the halls in my high school and getting this tremendous sense of destiny. Like I was supposed to do something really great. It was a really weird feeling. I feel like if I have an accurate view of myself, it frees me to be both humble and a megalomaniac at the same time.