Waking Dreams

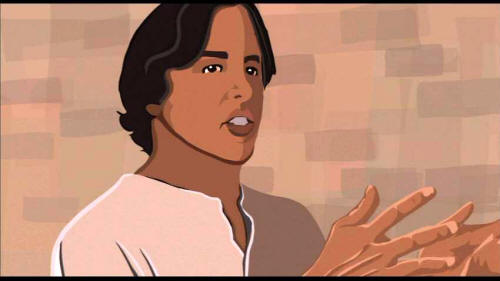

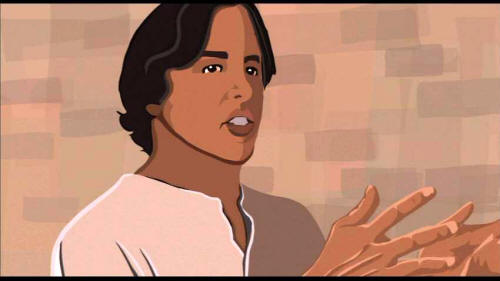

Working on the periphery of the Hollywood beast, Austin, Texas filmmaker Richard Linklater has already made a handful of great movies (Slacker, Dazed & Confused, Before Sunrise). But 2001’s Waking Life is a masterpiece: an idea movie that seeps into your dreams. Literally. The loose structure will be familiar to anyone who has seen Slacker: an unnamed young man, played by Wiley Wiggins (who also played the stoned naif in Dazed & Confused), wanders about, bumping into various philosophers, revolutionaries, artists, and kooks, and listening to their rants and rhapsodies. But the world of Waking Life is the world of lucid dreams, a world that, try as Wiley might, he can’t escape from. Riding Wiley’s eyes and ears, we are overwhelmed with information and meditations concerning consciousness, language, love, dreams, the future, free will, film, and the explosive poetry of being. If all those verbal wonders weren’t enough, the film is also marvelously animated, using a technique of digital Rotoscoping that “paints” over digital video images, lending the animation the shimmering, hauntingly familiar quality of old memories Ð or dreams.

Besides being incontrovertible proof that independent cinema is alive and well (at least in Austin), Waking Life may be the ultimate head movie. Though plenty of people wander out of the theater dazed and confused, a certain portion of viewers — psychonauts, edgy futurists, lucid dreamers, garage philosophers — will be drawn into an amazing liminal zone, at once strange and familiar, heavy and humorous, ordinary and indefinably important. Because most of us aren’t very adept at lucid dreaming or astral travelling, this zone will reminds most of us of drugs, but without the bells and whistles of hardcore hallucination (very little of the film’s considerable trippiness derives from “special effects,” and even then, they are subtle). But Waking Life isn’t about drugs, just as it isn’t about mysticism or the usual dream-movie plots. What it’s about is waking up: to the reality of our condition, to the apocalyptic madness of our historical moment, to the extrordinary potential lurking in our brains–and to the distinct possibility that what we normally take to be waking life is a deep sleep.

***

DAVIS: How much of the inspiration for Waking Life came out of your own experiences with dreaming?

LINKLATER: The narrative structure of the movie is 100% autobiographical. It was something that happened to me a little over twenty years ago — a series of lucid dreams and false awakenings. And this was before I was ever a filmmaker or anything. At that point, I just thought I’d be a writer of some kind. But that structure always stayed with me, where the lead character is very cognizant of the fact that he’s dreaming. And this was even before I knew what lucid dreaming was. It was just an experience I kind of flipped into.

DAVIS: What was the situation of your life when this happened?

LINKLATER: It was a school night, senior year of high school. No big deal. I wasn’t on any drugs or anything. (laughs)

DAVIS: Did it happen in one night?

LINKLATER: Yeah, not only did it happen in one night, it happened in like five minutes. When I finally did wake up, it seemed like the whole thing had taken literally weeks, just going around talking to people. I think it had a lot to do with being eighteen, with some existential crisis of that time period of my life. It got a little creepy at the end there, like, “Golly, am I trapped here forever?” And I’d ask people to try to wake me up, and it got really comical. And then I finally just kind of woke up. I had one of the early digital clocks, which I built in like 1976.

DAVIS: You mean like a home kit?

LINKLATER: Yeah, you solder it and you get the diodes and the resistors. I’m pretty good with electronics so I fashioned up this little clock that I still have to this day. And the same clock would tip me off that I was dreaming in the dream. I wouldn’t notice it and then finally I would and it would be all kind of scrambled, and I’d be like, fuck, okay, that means I’m dreaming. That digital imagery seemed to be my dream sign. And finally when I did wake up and I looked down across the room at the foot of my bed, I could read the clock. I’d gone to bed at around midnight, and it was like 12:05. I’d barely been asleep and I was drenched head to toe in sweat. I went and got a glass of water, and just went back to bed. I couldn’t get out of bed the next day. I slept until like 5. I missed school.

I believe there’s nothing in the human experience that can’t be explained; there’s precedent for everything. We all think we’re unique but we’re not. Over the years I kind of loosely got into dream research, or read things as they came up, but I never delved into it very much. And I had subsequent dreams, not quite that intense, but similar lucid dreams, where I was kind of aware I was dreaming. I did that fairly regularly.

DAVIS: Did you do it intentionally?

LINKLATER: No, it just kind of happened. I never would go to bed and say, “I’m going to try to have a lucid dream tonight.” I just would. I think I’m sort of predisposed to that a little bit, although all my research since then tells me that it’s a discipline anyone can do. I considered it just an event in my life like any other. But as a writer, and eventually a filmmaker, it always stuck with me, like, “That is an interesting narrative structure.” When you think of storytelling, it’s kind of the ultimate story. It’s sort of like the writer who’s writing a story about someone who’s writing a story, fiction that keeps looping in on itself. I think there’s something kind of primordial about that.

DAVIS: There are certain periods in media forms where there’s a highly self-conscious understanding of the frame that creates the narrative inside the media. And it often gets played out early in the history of the media. For example, if you look at the history of animation, you’ll see that at the very beginning, when people are first starting to screw around with animation like Fleischer’s Koko the Clown, there’s a lot of awareness of the frame. There’s a lot of characters jumping off the page while the guys are drawing them.

LINKLATER: There’s a great Tex Avery where he erases Donald Duck’s mouth.

DAVIS: Exactly. A similar self-consciousness is also in narrative, in storytelling, like in The Arabian Nights, where you have these collapsing story frames. There’s a story within a story within a story. And as you’re reading, you almost get to that Waking Life state because you keep getting deeper and deeper into these stories, and then you break out again. There is something very primordial about it, even though it seems kind of avant garde because it’s fucking with your expectations.

LINKLATER: Expectations in your head, when you think of fictional constructs. But I think what these things are getting at –and this is what I was trying to do — is to point out how your brain really flows, or how thoughts follow thoughts, or how the narrative of your own thinking unfolds, or the narrative of your own life. This process is very digressive and it has no set path, and it does fold in on itself. Someone will say something that will tie you back into a story that is much older. So for me, I always felt like I was trying to get closer to my feelings of how the brain worked, and how this shit kind of unfolds.

DAVIS: How much of the film’s actual content — the segments, the discussions, the weird characters — were you just making up as a storyteller? And how much of that had you experienced dreaming or heard about other people experiencing?

LINKLATER: Well, that’s a whole different realm. On one level, I was trying to capture the intensity of that dream I had, and the content of it, although I don’t remember any of it word for word.

DAVIS: Did you write it down at the time?

LINKLATER: No. It just seemed so real. I tend to remember dreams pretty well. I remember them like they’re real experiences. But no, I didn’t write it down. In the movie I was trying to capture that feeling that there was some important transformation going on, right at the tip of my experience. I just tried to capture that feeling of potential. There was a certain newness in the air that I felt. But then the actual content of the film came out of a jump ahead twenty years to the present moment, and my own thinking today. I keep notebooks — thoughts, ideas, experiences, quotes, a great paragraph out of something, just typical writer kind of notebooks — and a lot of it came out of there. I recycled stuff from other films that hadn’t made it in. So it was sort of a kitchen sink. That’s the same way I worked on Slacker: a lot of information from a lot of different places all finding a home where they wouldn’t in a typical narrative. None of this stuff kind of “qualifies” to be in a movie. It doesn’t progress a story or the character traits or any of that shit.

DAVIS: The second time I saw the film, it seemed to me that there was more of an evolution than I first perceived in terms of the ideas and the experiences that Wiley is undergoing. There is almost an initiatory quality to the order of events.

LINKLATER: There was a natural order to things, the way the story progresses. It kills me when people say there’s no story. I say, “No no no, there is a story, it sneaks in the side door.” The story is there, it just doesn’t present itself. Like a lot of things in life, you just become aware of it. Once you’re aware of it, that’s the story. It just doesn’t present itself in the first act of the movie in the traditional three act structure. It sneaks into the movie and then you realize what story you’re in. To me, that’s a lot more like life. You realize what’s really going on. It’s been going on all along, and then you just become aware of it. When you learn things, that’s how it always is, it’s like, “Oh, now I’m aware of this,” and then you see it everywhere, then it permeates your thinking and your experience.

The content came from a lot of different directions. A third of it was shot as written, a third was something I wrote that we rewrote in rehearsal with the actors, and another third basically came from the actors. I call them actors, but a lot of them were just professors and interesting folks who I encountered. In my casting, I would say, “Well, give me the most intelligent, cool people you know, I don’t want actors, I want fascinating people.” And so I just sat down and started talking to them, and one of the questions was always, “Well, what are you most passionate about? What do you think you know more about in this world than most people?” And so a certain amount came out of that. We would just start talking right then. They’d come back maybe several more times and then we’d just work on a scene. And it was up to me to go, “Well, I think this fits in thematically.” I had a lot of funny scenes that were a little too tangible, a little too blunt. However funny and informational, they were just a little too real, so I ended up either not shooting those or cutting them out. I just kept things in there that were sort of, you know, I guess less rational…rational’s not the right word, but…tangible maybe.

DAVIS: I’m not sure whether or not you were conscious of it, but it seemed to me that, in terms of the more philosophical rants Wiley hears, that the ideas built on the previous raps he’s heard, that they actually moved forward…

LINKLATER: Yeah, a lot of that I moved around in the editing room. You remember the one right off the bat, where the professor is talking about existentialism as being more than a fad from previous generations? I first felt that it belonged near the end of the movie. But it really worked better as a formative idea for the movie, and I discovered that in the editing room. I thought, “No, let’s say that up front. Your life is yours to create.” To me this resurgence of the subjective is very important. Your ideas are who you are, you do make a difference. Personally, that was just my own feeling of coming around, having gone through postmodernism. That was my own and I think a lot of people’s philosophical trajectory. Postmodernism jerks the carpet out from underneath you and pretty soon you’re in this hall of mirrors. I just found myself cycling back to old ways of thinking, but in new ways. I guess it’s just the cycle of life. I was really interested in things I hadn’t been interested in for 15 or 20 years.

DAVIS: Like what?

LINKLATER: I was reading, oh, everything from existentialist writers to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sartre, stuff that I first read at a young age. It seemed very different to me now, it meant completely different things.

DAVIS: That philosophical trajectory is one of the things about the movie that for a certain section of the audience is really going to hit home. That’s one of the main things that I struggle with: how do you re-affirm or approach the question of human subjectivity when there are so many things that are blasting it away, from postmodernism to all our new neuropharmacological models of subjectivity. Everything is ready to pull the rug out from under your own unfolding subjective experience, so how do you come around and reaffirm that? Because to my mind, if you lose that thread, if you lose the ability to sustain and affirm that particular flow of experiences, then really you have kind of capitulated to the more nihilistic and frightening aspects of our moment, philosophically and technologically.

LINKLATER: I know, it’s sort of frightening. I mean it’s very real, but I think humans do have that subjective ability to claim their place. That’s why I found myself back in the nineteenth century with Thoreau and Emerson, the original transcendental subjective guys. When they thought of God, when they cut out all the middlemen, it was complete: your own experience, your own development and your own world, was everything. My favorite Emerson quote is, “Ideas are real. Thoughts are real.”

DAVIS: And that’s sort of the lesson of the lucid dream world. You’re giving in to whatever situation you find yourself in but still trying to be true to yourself, and then suddenly you’re translated into a space of lucidity, and you know that it’s your will and your imagination that are partly constructing your experience. Then you can’t avoid the existential burden of having to create your life, because you’re in this plastic world that is a creation of yours. You can’t shuck it off, you can’t say, “Well, I’ll just let something happen,” because that’s what’s happening: your need to choose.

LINKLATER: Yeah. You are creating your world. This is all a visual construct and the brain’s processing and doing it all. That’s why it was a nice parallel life for me, diving into the lucid dream world by going forward with this movie. I had the wonderful experience of my waking and dreaming states becoming very similar to one another.

DAVIS: Did you start lucid dreaming more when you were working on the film?

LINKLATER: Every night. Even during my waking hours, I would walk through kind of wondering, “Is this a dream?” I was asking myself that every five minutes. And it was wonderful. It’s really a great way to go through life. I had a very superficial knowledge of lucid dreaming before jumping into this movie, so I had several months of just reading everything I could get my hands on, really concentrating and starting to do some of the discipline things that I had been tipped off to in Steven LaBerge’s work. It confirmed a lot of my own experiences — like the fact that its hard to adjust light levels, just like it’s difficult to call up your name.

I was getting challenged every night with these things. I would be in a production meeting on the movie, sitting there with my producers and a couple other people, and I would be explaining to someone how it’s difficult to adjust light levels in lucid dreams. And I would get up and I would flip the light switch, because I’d trained myself to do that in my waking hours. Every time I mentioned it, I had to go do it. I would walk across the room, flick the light switch, say okay, it works, so we can all go back to work because this is the real world. You know, I’d make a joke. But often I’d be in that meeting and I’d go over there, and I’d flick the light switch, and it wouldn’t work. And I’d just kind of laugh and go, okay, I’m dreaming. Typically in that situation, once you’re really cognizant of the fact that you are perceiving a mental model and the people are dream people, they get real quiet, because you’ve sort of robbed them of their…it gets a little tricky at that point. Often I would just say, “Now that we’re here, we’re shooting that scene where Wiley floats through the wall, so at least I’ll get the right angle.” So there was a complete blur between my waking and dreaming.

It was very poetic, because you notice everything. You’re very attuned. You’re like, “oh, that tree,” and you’re asking yourself: Is this a dream? I came up with that line that to me kind of sums up the whole movie: “Most people are either sleep-walking through their waking life, or wake-walking through their dreams. Either way you’re not going to get much out of it.” I’ve had people say, “Well, I don’t want to control my dreams, I like the way they just kind of flow and flow.” But no one who’s ever had a meaningful lucid dream experience would ever say that.

DAVIS: You talked about going through scenes for your movie when you were in the dream world.

LINKLATER: The scene where the woman confronts Wiley, and goes on the big rant about the soap opera she’s doing, and then he realizes halfway through the scene that he’s dreaming — that really happened to me. Somewhere in early production, I was listening to this woman talk and I realized I had a watch on. I haven’t worn a watch since fourth grade. I look at it, and I can’t read it, so I go, “I’m in the middle of a dream.” But I don’t just say that, instead I go, “Hey, I’m making a movie, and I want to know who you are. Tell me all about your subjective experience, because it’s really interesting to me who you are.” You have to get really calm — this is the discipline aspect — because it’s easy to freak out and either wake up or float up. So I actually was able to have this conversation with her. But when I threw it all on her, she just sort of threw it back on me. She says, “Well, who are you? Do you know your name?” I’d read probably two days before in my research that it’s hard to recall your name in dreams. You can, but it’s difficult. So I go, “Ah, this is a test, can I recall my name?” And I really concentrated, and I was able to pull up my own name. But I didn’t give Wiley that ability, because I thought it would be interesting to have a lead character who has no identity. He is strictly a floating perspective. I thought it would be funny to be more than halfway through the movie and then realize that the lead character has no idea who the fuck he is.

DAVIS: As you started doing dream research, I assume you met people or talked to LaBerge. What was your impression of the state of the lucid dreaming scene?

LINKLATER: All I did was read. I didn’t have many conversations outside of people I was working with. I kept it pretty close. I only met LaBerge recently, after Waking Life was finished. I wanted him to see it. We hooked up in San Francisco and I had a really good time with him.

DAVIS: But you have tried the Nova Dreamer [a device designed by LaBerge to trigger lucid dreams by emitting light signals through your closed eyelids when you go into REM sleep].

LINKLATER: Yeah, I have a Nova Dreamer. I used it last night. I think it’s interesting. I was lucid dreaming naturally when I was making the movie, but as I finished it and got farther away from it, even into the editing, I quit having my lucid dreams as regularly, and then pretty soon I was hardly having them at all. So the Nova Dreamer is sort of a short cut that I’m still incorporating. It has a different quality, but I’m sort of enjoying it. You get these little flashing lights on your eyelids, so flashing lights become a dream sign whether you like it or not. If you see a flashing light in your waking life, like somebody blinks the lights in the lobby before the play starts, you have to check: is that a sign? Because then you’re going to be in a dream, in a trench in a war with a rifle and a couple other soldiers and bombs going off, and then you’ll have to think, was that a flashing light? Oh, okay, shit, I’m dreaming. Those explosions are flashes that you have incorporated into your thinking.

DAVIS: One of the things that interests me even more than the magical ability to control these dream spaces is the moment where you wake up inside of the construct. That particular little passage has always really attracted me, because it’s that passage that for me has the highest density of the quality we were talking about earlier, that sense of imminence, of some tremendous potential just around the corner. A lot of Phil Dick, who you mention at the end of the film, deals with these breakthrough moments. How does information come in from outside of your reality bubble and create cracks that then allow some other change to happen that affects the entire structure?

LINKLATER: There’s a total poetic moment where you’re overwhelmed at what’s created there in your brain. And you truly don’t know where it all comes from. That’s the eternal mystery, and to this day, I waver a lot in my thinking about it. I like to think that on some spiritual level or a human consciousness level that there is this interconnection. The film dealt with this a lot, it hints that we are sharing thoughts and experiences, there’s this psychic space out there that we’re all tapped into. But sometimes I’ll think, well, no, we’re all totally these biological entities. There aren’t those connections, this stuff is coming from your own experience, and you’re just not aware of it. I wish someone would tell me.

DAVIS: That’s the big koan. But the fact that you can create a materialistic explanation for altered states — spiritual experiences, lucid dreams, and so on — should no longer prevent us from exploring them. That’s what’s happening now, it seems to me. That’s one of the ways that this whole conversation connects up with psychedelics, because psychedelics present a similar paradox. It’s completely obvious that I am taking a molecule that affects me on a biophysical level. I take it, then my body metabolizes it, and then it goes away. And yet, does that mean that when I’m experiencing these amazing things, I’m going to sit there and go, “Ah, this is just some crap in my brain”?

LINKLATER: It’s about finding those hidden passages, those areas that you have to sneak into somehow, however you get there. We all want to transcend and get there. You can take drugs. You can meditate for years. You can have a temporal lobe seizure.

DAVIS: There’s one thing that I always come back to, that’s also explored in the Ethan Hawke sequence of your film. Maybe all these intimations of immortality we have, these hints of a future bardo state or an otherworld or a heavenly world — maybe they’re just strange premonitions of what happens when the biological brain dies. There is no carryover into another world, but nonetheless, when you greet that experience, the idea of somehow preparing yourself for it becomes paramount, because you still have to go through it. So when people walk away from Waking Life, a lot of them are going, “There’s this whole world out there that I’m just not dealing with.” And why wouldn’t you want to do this? Not only is it fun, but it might actually be important on some level.

LINKLATER: On one level, I don’t know of anything more important. In my thinking, that’s what it’s really about. To me, the right analogy for watching Waking Life would be a lucid dream versus a regular dream. In the regular dream you go to a movie and it just unfolds and you take it unquestionably. But Waking Life by design demands that you acknowledge it. You have to kind of participate in it or you don’t get anything out of it — you’ll hate it, you’ll not get it. So there’s a certain how-to manual aspect of Waking Life in the realm of lucid dreaming. It sort of tips you off and helps you align and then hopefully takes you along on this experience that to me is analogous to the dream itself. It’s what you’re up for at that time. If you’re not up for anything, the movie totally blows.

DAVIS: Tell me more about your reactions to other people’s reactions.

LINKLATER: I’m overwhelmingly touched. I knew I was putting something out in the world that could be powerful to people who are on this particular wavelength. Sure enough, that response has been really heartfelt and really positive. Others are just like, you know, “I just didn’t get it. I thought it was boring or preachy.” And that’s just fine, you know, whatever. I was always moved by people who talked about the positive. They said it was a “yes movie.”

DAVIS: I think that’s very true.

LINKLATER: That’s what I wanted, it’s this totally non-cynical, positive vibe.

DAVIS: Although there’s some very powerful darkness in it…

LINKLATER: No, it’s potentially very dark. I thought that was very important, to be honest, because that’s the gambit. I felt it was very important to have extremely dark areas.

DAVIS: For one thing, in both the movie and your original lucid dream, there is this great horror that you’re stuck, that’s you’re not going to wake up anymore. With psychedelics, people often get to this point where they feel that they’ve gone to far, that they have reached some pocket of timespace that they are never going to escape. That kind of waking death is one of the major fears you deal with when you move into this kind of lucidity, whether it’s in dreaming or other altered states. Part of you wants to go back, to know that you can go back to sleep and then wake up in the morning and feel the constraints of normality. There’s something extremely refreshing about it once you’ve been blasted open. Before you’ve been blasted open, it may feel like a prison, and then afterwards you’re like, “I just want to curl up with my lover, drink a beer, and go to sleep.” It reminds me of that scene in Waking Life with the guy in jail who is consumed with rage, who imagines a very interesting torture experience. He talks about pulling off his enemy’s eyelids off so they can’t shut out the sight of him slowly pushing a lit cigar into their eyes. In other words, they can’t go to sleep, they can’t stop being aware of what’s going to happen to them.

LINKLATER: I’m glad you picked up on that image. That’s very important — cutting the eyelids off, that idea of being awake. People say, “Oh that’s so dark,” and yeah, it’s dark, but look how he’s keeping himself alive on more of a tangible, sociopolitical level. This guy is in a jail, and that’s what’s keeping him alive, his own imagination.

DAVIS: That’s an example of the aspects of the movie that are very Tibetan. The hell realm is not some external place, but something that you have access to through your own violence and your own imagination.

LINKLATER: Yeah, even if it is just in the dying brain, heaven or hell are lived in those last few real-time minutes and however much cognitive life is mustered in that time frame. I think those are probably good analogies based on your own beliefs and thought processes and how much you have or haven’t prepared yourself. I like what you said earlier about the preparation aspect, of not being afraid. I think that’s a real important thing. When I was younger, I’d read about psychedelics, but I thought, “That’ll really trip me out, there’s a certain danger element to it.” Once I was talking to some old guy who I really respected, and I described my fears, and he goes, “Being afraid to take psychedelics is much worse than anything that could ever happen in the trip.” And he had a point, and I tell people that to this day. Being afraid of the experience is ultimately much more harmful to the general way you perceive your life than anything that could happen to you in the process.

DAVIS: There is an initiatory quality to Waking Life, in the sense that it’s full of cues and clues that, if you’re already primed, will really give you a deeper sense of possibility about your own dream state. The scene for me that really nails that down is the one that takes place in the white room where Wiley meets those three guys and first tries the light switch.

LINKLATER: I call that the “dream room,” where they’re all specifically talking about dreams.

DAVIS: There’s something very interesting about the fact that there are three of them. I think of them as dream angels, initiators. Even the windows in the room are peaked, like church windows.

LINKLATER: Yeah, sort of stained glass windows. That building is not used as a church now, but it used to be a church. That was a perfect setting. Strange scene.

DAVIS: It’s also the scene where you get probably the most “reductionist” rap in the whole movie, where the first fellow explains that as far as the brain is concerned, there really is little different between waking and dreaming, except that in waking life our serotonin levels suppress memory in order to keep us focussed on the immediate situation.

LINKLATER: Right, there’s some dense stuff in there, but I thought it was important to get the science out there.

DAVIS: Besides the science guy, you have the sociopolitical commentary by the guy with the ukulele, who talks the horrible experience of dreaming you are at work and then waking up and realizing you actually have to work all day — and then resisting that. Rounding it out is the crazy “id” guy who talks about how much fun you can have. The whole encounter reminded me of certain experiences on psychedelics, when you’re suddenly confronted with knowledge that you haven’t had before, knowledge that’s kind of creepy but also kind of liberating.

LINKLATER: Initially I wanted to put that stuff in different points in the movie, but the more I got to thinking about it, the more I thought it was much more fitting to put those three back to back. By the time Wiley floats out of that room, you’re really at some new level.

DAVIS: Tell me about the character who seems like an alien, the kid who speaks in a very detached monotone about human life?

LINKLATER: That scene has a funny lineage. My animation partners on this, Bob Savison and Tommy Palotta, had done a short film called Snack and Drink that I think’s going to be on the DVD. And it’s about that guy. His name is Ryan, and he was a 13-year-old autistic kid who they knew. They just shot some video of him walking up to a convenience store and getting a snack and a drink and talking about cartoons and music. He’s kind of regurgitating a litany of things — you know how autism works in the mind. So they were like, “Hey, you’ve got to get Ryan in here somewhere.”

I did have room for a teenager, but then I thought of another idea. I always had this idea as a kid, that you’re in a science fiction sort of world and that you would encounter an alien who had been here a thousand years. He had kind of used Earth up and was departing, and you encounter him at that moment, on his last day.

DAVIS: There’s a weird relationship between certain aspects of functioning autism, and the ability to detach and see through the trance of ordinary life. Whether or not you think of it as a serotonin trance, you can see our conventional reality as an emotive mammalian thing. You know, mammals evolved emotions to deal with social reality, that’s clearly part of what maintains our sense of consensus reality.

LINKLATER: Yeah, it’s a very adaptive thing for humans.

DAVIS: Right, but autistic people don’t deal with emotional or social codes in a similar way at all. There’s this weird quality to autism that you can also associate with people who have gone way beyond this stuff, who have transcended the world in some kind of way. What I like about that scene is its strange, simultaneous quality: you don’t really want to be the alien, but on the other hand you see that if you keep doing this human thing, eventually you’re going to get there.

LINKLATER: Yeah, they’re beyond us at this point and you’re not sure you want to be that guy. But then if you really just visit that place that they’re occupying, which is sort of like the mystic or the holy man who’s meditating, you kind of want to go there. But you’re not really ready to give up all your earthly delights. We love all that emotion and shit, you know, as painful as it is sometimes.

DAVIS: That comes around to what a “yes movie” Waking Life is. You can talk about it philosophically or you can talk about it just in terms of its overall feel. But if you lay out the more philosophical discussions or monologues that Wiley hears, they really do build toward a certain kind of, I don’t know, “posthuman humanism.” We’ve blasted apart all of the old conventional ways of continuing to be human beings. Our perception of ourselves as willing, loving, imaginative creatures doesn’t really work the way it used to. That’s the posthuman part. But on the other hand, as we go into all of these new and alien spaces, whether we are talking neuropharmacology or genetic engineering or these lucid virtual spaces, that doesn’t mean we stop willing and imagining and emoting and doing all of that familiar stuff. The qualities we like about human beings actually have a role to play, a new zone of expressing themselves in new ways. That’s very different than saying, well from here on out we’re just Darwinian machines and you might as well give up on all those old stories.

LINKLATER: The human essence is seen as being left behind to these almost zombie-induced forces…they’re seen as so cold and sterile and nonhuman, but I think it’s really just the opposite. I mean, the development that humans are doing is ultimately to progress, and a lot of that progression is human consciousness, whether we’re aware of it or not.

DAVIS: It seems like the dream state is one of the best places to work with in terms of developing the discipline of consciousness.

LINKLATER: I think so. It’s a fascinating place, really endless. I think more people need to pick up the ball and run with it in that realm.

DAVIS: Can you talk about your plans to adapt Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly to the screen?

LINKLATER: It’s in its earliest phases. We want to do it as our next animated feature. Who knows how these things ever work out. I’m working my ass off on it, though.

DAVIS: What attracts you to A Scanner Darkly?

LINKLATER: As a Dick fan, to me it always felt like it was incredibly personal, like this was his life, these were his friends, this was him. On a human level, I love these people and the culture at that moment. On a social level, what was seen as sci-fi paranoia back then has actually come to pass. What for him was the near future seen from the mid-70s (he set it in ’94 or something), is where we’re at right now as a society, with surveillance, face recognition, etc. I’m really going to run with that aspect of it. There’s just no privacy any more. Your house is being scanned, there are scanners everywhere, you’re even likely to find employment narcing on your friends.

I was in LA in a rental car for one day about a month or two ago. It was like 10 at night. There’s nobody around, I approach the intersection, it turns yellow, and I do the typical thing, kind of scoot out into the intersection. You know, the light turns red while you’re in the intersection but you go through, right? That’s what we all do. I get a ticket in the mail with a picture of my car in the intersection with a little time line next to it, a little number, I get a close up of the license plate, a close up of me behind the wheel of the car, and a ticket for $270.

DAVIS: Wow.

LINKLATER: That’s just the beginning. How long until we get tickets like, “Okay, you jaywalked at 4:30 a.m. on East 42nd Street in New York, you owe us a hundred bucks.” How long until it’s like that? It’s just kind of scary. They tracked me down through the rental car company. I never talked to a human. That kind of thing wouldn’t fly in Texas, at least it wouldn’t today. But things like that start in California and work their way east. With the whole post-September 11 attack on our rights, it’s just a matter of time. Every phone’s tapped, they can just search anything. The part of me that’s always on about control and the big brother stuff, that’s flourishing in this story. I’ve updated it a little bit, but it’s very true to the book. I’m not doing anything too radical.

DAVIS: Obviously you can’t really do a drug movie that’s some postcard fantasy about how marvelous drugs are. But though A Scanner Darkly is in some ways an anti-drug book, it’s also incredibly sympathetic with the reality of these things.

LINKLATER: Of these people. Because they’re not bad people. They’re addicted to Substance D, but they’re just guys working on their cars, trying to get along.

DAVIS: What about the idea you float at the end of the film, that time is a way of resisting the eternal now that’s always right before us, awaiting us with open arms? Where’d that come from?

LINKLATER: I like that sentiment. There’s that idea that there is just this moment, and you’re creating everything beyond that. It’s such a clich, people are always like, “Oh, be in the moment,” but you know…

DAVIS: If you really try to accept that experience, there’s a tremendous amount of fear and exhilaration that goes into it. Like you say in the movie, we resist that freedom. But it’s such a clich 70s-ism that it’s kind of hard to make it come alive.

LINKLATER: Not that they weren’t onto something then. They were trying, it was a good step. When you talk about all the hypocrisies in the official drug culture, well for 35 years now, everybody kind of knows the truth about all that. But it’s going to be up to someone to take a leap forward and really move us out of the negative horror story of prisons and criminalization. I think the way you get these kind of sea changes isn’t like political overnight stuff, it’s generational. All the old folks who just knee-jerk vote for the guy who puts the most drug offenders in prison are going to die off. Hopefully some people who are a little more tolerant will replace them, and maybe we can move forward.

DAVIS: That would be nice. So how did you choose that particular style of animation that you used in Waking Life?

LINKLATER: I never thought I’d do an animated film. I never thought about it in terms of this story. But a friend of mine developed this software that enables you to digitally paint over existing imagery, a computer variation of Rotoscope. That’s when it clicked: “Oh, that’s how that thing I’ve been thinking of for twenty years, that’s how it should look.” That’s why the film in my head all these years didn’t work. It just didn’t work with live action.

DAVIS: You need to have that kind of slightly surreal layer that’s still really close to the everyday.

LINKLATER: If you’re going to try to depict an unreality in a realistic way, it’s perfect. On one level the animation is real, with real people and real voices. Yet it’s obviously a visual construct. So your brain’s kind of put in the same place as when you process your memories or your dreams, where by definition there’s a imaginative constructive element going on with the visuals. That’s the perfect analogy for this movie, because the audience member has to work the part of their brain where this movie takes place.

DAVIS: One of the most unusual things about the animation is that the style changes throughout the film.

LINKLATER: Different artists drew different people so inevitably they had a different style, a different look to them. I thought that was important in a film that is so much about individuality. These animated people seem to care about the human experience of individuality. It’s ironic that they’re animated characters and yet they seem more real and individual than so many other things — especially animated films, where there’s obviously one ber-designer and three hundred drones working together to make everything the same way.

DAVIS: The animation also increases the sense of passage. The whole idea of a bardo is that it’s an in-between space, it’s moving between X and Y. In Tibetan Buddhism, the bardo isn’t just where you go when you die. There’s also a bardo between sleep and waking, between birth and death, and even between every moment of the day. The more that you can communicate that or draw people into that sense of a liminal, in-between space, the more you can get that kind of energy going. So by changing styles, it’s like we’re getting a subtle cue that we’re on the move again. The universe has shifted a little bit.

LINKLATER: Yeah, don’t get content with your reality, because it’s not really there. Don’t think you know anything. That’s the Buddhist thing: you do your work and when the situation arises, the knowledge is revealed to you. You always have to be putting yourself in the situation where you’re open to that revelation.

DAVIS: That’s why I think the positive vibe of the movie is important, because it affirms individual subjectivity. If the world gets weirder and weirder, and the world of consciousness gets weirder and weirder, the one thing you’d hope is for people to be able to be balanced or centered or firm just in their own experience.

LINKLATER: Yeah, you have to be your own editor in this world. There’s so much out there. You have to be your own little weather vane, you’ve got to be in touch with your own muse. You need it as an artist, as someone trying to create, but also just to proceed through life and feel okay about the world. We’ve been given an amazing opportunity by being human. Our own brains are incredible, so don’t hand yours over to some middleman to feed you and tell you what’s going on. You have to take control. No one’s ever the worse for that.