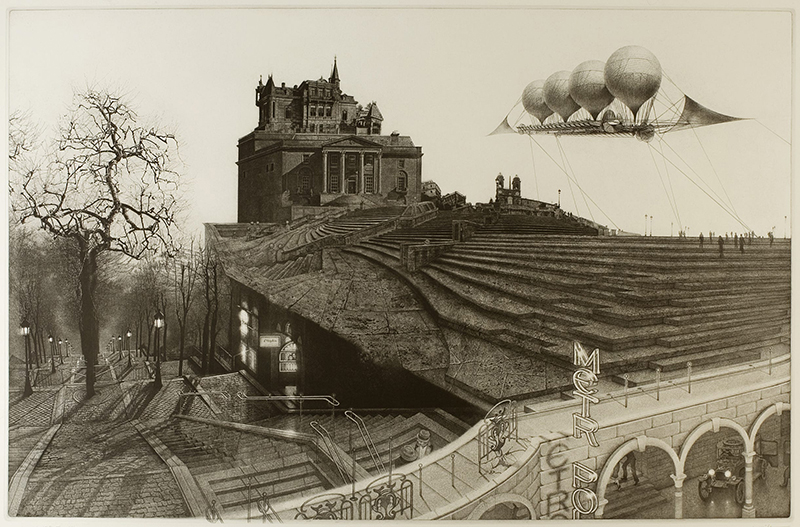

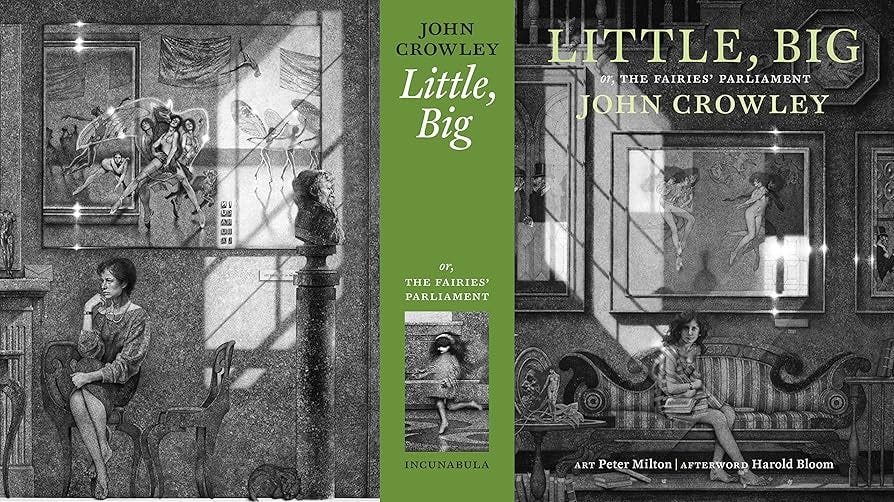

This summer, I turned to the recent 40th anniversary edition of John Crowley’s masterpiece Little, Big with more weight than I usually bring to the reread of a literary fave. Some of the weight is literal: while this lovely hardbound edition, with copious illustrations from Peter Milton, is definitely one of the more beautifully produced and designed volumes of contemporary fiction I own, it is also fucking heavy. Like six pounds heavy. And while my long-standing preference is already to do serious reading at a table or desk, rather than a sofa or armchair, I had no choice in this case. Since I was committed to reading this puppy entirely in volume, not supplemented with audiobook streams or the iPad that lies next to my insomniac bed, I was almost literally chained to a desk.

But what sweet capture! Little, Big is such a great book I am tempted to simply urge you to get your hands on this edition, work through its 800 plus pages, chart the leaps and pirouettes it inspires in your own imaginative dojo, and then just get back to me. But I also want to share something of that other heaviness that I brought to this read: a somewhat Saturnine weight caused by the recognition that, after decades of chasing, finding, and metabolizing the weird and wonderful, a strange sobriety often settles into my bones. This is not some nihilistic defeat, or conversion to pure materialism. The mystery is still part of the picture. My own meditative and philosophical practice regularly tunes me into the vast and vexed mystery of things-as-they-are, that charmed and evanescent immanence that Buddhists call thusness. But compared to my twenties, when I first read Crowley’s book, I am less compelled by more bold magics, whether they take the form of drug visions or esoteric schemas, dream encounters or ritual devotions, mad infatuations or paranoid narratives.

I suspect a lot of it has to do with the mainstreaming of the Weird; from psychedelics to UFOs to conspiracy theories to AI dreamscapes, we are now saturated in cynical ersatz enchantments. In this I remain a classic bohemian: I cannot believe the good stuff lies where everyone else is looking. So while I am not losing my taste for what Little, Big calls “the sweet unreasonable air of wonder,” I do seem to be refining that taste, as if it were that air itself that I yearn to breathe, clean and clear and utterly transparent. Real enchantment, I have come to suspect, is not a matter of technique, but a rare matter dependent on grace as much as works, both of which require luck as well as labor (for even grace requires the labor — or is it luck? — to notice its operations in the first place).

One of the many marvels of Little, Big is that Crowley manages to both serve up a banquet of subtle, oddly familiar, and uncanny wonders, while at the same time reflecting, over the course of the novel and its rich weave of characters and relations, on the tricksy and ever-so-subtle dynamics of wonderment itself. The story begins when Smoky Barnable, the central character and the loose stand-in for Crowley, who is a pretty down-to-earth sort, leaves the City and marries into an upstate family who inhabit a vast architectural folly, designed by an ancestor, called Edgewood. The fate of this clan is shaped by something they call the Tale, a narrative that overlays the one we follow, back and forwards in time, and that is moreover interwoven with a host of largely invisible (or not) Others: elves, talking animals, oracular devices, and most of all, faeries. But, like a number of his male in-laws, Smoky never really quite sees or believes this stuff, and his proximity to a “vast superfluity of ambiguous evidence” only creates a space of poignant and sometimes absurd suspension wherein many of us will find ourselves, suspicious too of narrative pareidolia, at once wanting and refusing to fit this otherworld into the one we know. And Crowley gently and brilliantly plays with our longing to both know and not.

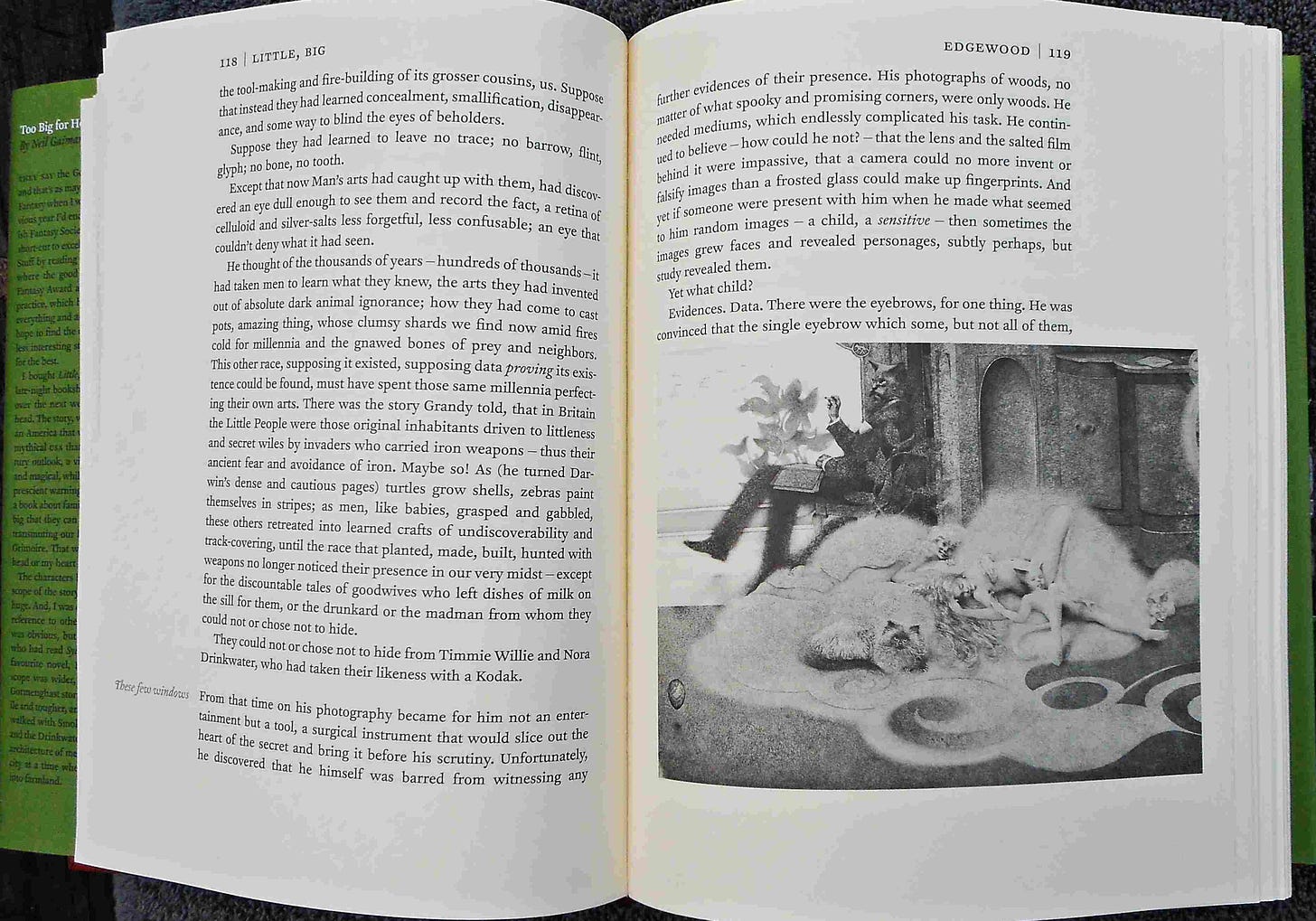

The wit and sympathy of Crowley’s approach to the gloaming of real enchantment is signaled by the novel’s first explicit glimpse of the paranormal. Distant uncle Auberon did not believe in “Them” until he glimpsed, in a photograph he had taken with his relatively new-fangled camera, a foot-high personage with pointed shoes and a tall conical hat. Crowley’s invocation of photography here is significant and multilayered. For one thing, it indicates the modernity of his frame — Little, Big is no reactionary retreat into the timelessly rural, or even the Victorian, and half the novel takes place in the city that Smoky flees. But modernity is also an epistemic mode we cannot simply leave at the door. When Auberon the younger, Smoky’s son, pours over his namesake’s ancient photographs, he makes a discovery that today’s UFO true believers should really try and metabolize:

“Note thumb,” old Auberon would write on the back of a dim view of gray and black shrubbery. And there was, in the undisentanglable convolvulus, something that looked very much like a thumb. Good. Evidence. Another, though, would annul this evidence entirely, because (with only speechless exclamation marks on its back) here was an entire figure, a ghostly little miss in the leaves, with a trailing skirt of dew-glistening cobweb, pretty as a picture; and in the foreground, out of focus, the excited figure of a blond human child looking at the camera and pointing out the wee stranger. Now who could believe that? And if it was true (it couldn’t be, how it had been faked [younger] Auberon had no idea, but it was just too stupidly real not to be fake) then what good was the maybe-a-thumb-in-the-shrubbery and a thousand others just as obscure?

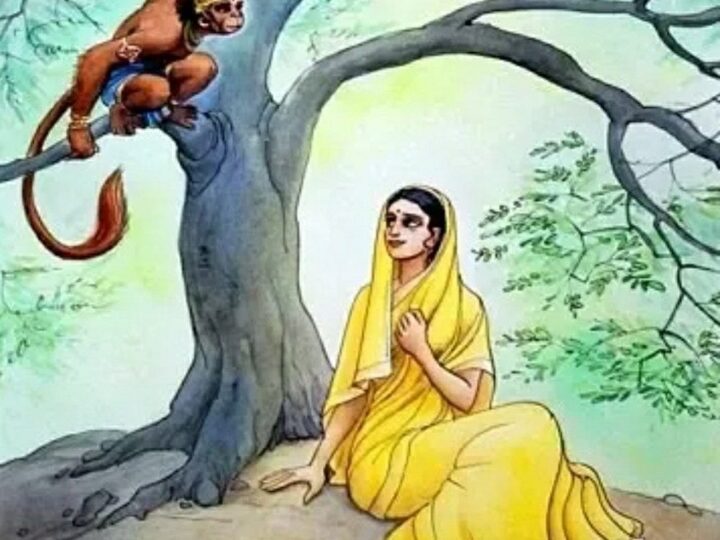

For the esoterically informed, this wee stranger will be familiar, for it is nothing more or less than a Cottingley Fairy, one of those — to our eyes — obviously hoaxed photographic phantasms that managed to convince paranormal-curious Arthur Conan Doyle of the reality of the Fay barely over a century ago. But the real magician here in the image, which Crowley knows as did Lewis Carroll — whose Wonderland forms the template for Little, Big’s conjunction of dream to system and architecture — is the blond human child.

One of Little, Big’s considerable charms is that, while it is very much a big person’s book— long, literary, with adult characters that struggle, albeit with a definite lightness, with aging, obsession, and despair — Crowley draws much of his phantasmal lore from the archives of the first decade: the baby-hauling stork makes an appearance, as does Santa, invisible friends, all manner of diminutive talking animals, and, of course, storybook faeries, with pointed shoes and conical hats and quaint little gingerbread homes. This might sound vaguely repulsive, but fear not. Katharine Kerr has compared the reading of Crowley’s novel to watching a high-wire artist: “one slip and he would fall into the dreadful net of Twee. Yet Crowley never slips, not upon a single word, and the book grows more powerful with every page.” And it grows more powerful, in part, by attracting, as with the subtlest of magnets, the finest and most forgotten filings of our own remembered imaginings.

This deep draw from childhood helps explain the novel’s disarming shine, a marvelous atmosphere that Crowley calls “the deep real summer of childhood.” In his meandering closing essay (previously unpublished), massive Crowley uberfan Harold Bloom reminds us how few successful arcadias appear in twentieth-century literature. Edgewood is such an Eden, one whose occupants feature a poetic but unsentimental coherence that reminds me of the extended family in Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, a secular narrative itself not untouched with moments of uncanny enchantment. Extended family is key to Crowley’s web of enchantment, since it conjoins the two most reliable fonts of real enchantment that exist in most people’s lives: childhood and eros. Families are nothing if not eros and its consequences, after all, and it’s Little, Big’s broad (albeit PG-rated) attention to eros — to attraction, coupling, long marriage, lost loves, and mad infatuation — that tie its deep real summer to our more flickering adult lives.

Crowley also knows that there is an esoteric side to eros as well, one that goes back at least to Plato, and even further to Hermes, mischief-maker and flirt, but also psychopomp. The imagination is an erotic domain; the images of the loved one that obsess the infatuated run on the same fuel that conjures gods and discovers oracular significance in common events. Indeed, Crowley’s exceptional and poetic understanding of hermetic traditions — as brilliantly on display here as it is in his masterful Aegypt tetralogy — is of a piece, Giordano Bruno-like, with his attention to the nuances, fire, and ordinary magic of erotic bonds. The importance of these bonds is one of the reasons that Bloom identifies the genre of Little, Big not as “fantasy” but as “visionary romance.”

But there is another key to this Ovidian lightness: unlike most fantasies, and certainly the more heavy-duty ones, Little, Big is decidedly not Manichaean. There is no Sauron, no Voldemort, no Metatron. There is an outsized disrupter — the uncanny demagogue Russell Eigenblick, who becomes president of the United States — and the book itself grows increasingly apocalyptic in its final third, suffused with a “premonition or an intimation of revelation,” which is how Crowley describes the heart troubles that eventually take Smoky. But even Eigenblick’s narrative is shot through with ambiguity, and he winds up playing a more complex role in the Tale than at first appears — at least to the extent than any of Little, Big’s muggle readers can really track the Tale.

The weight in the novel comes rather from time, and decay, and the motif, familiar from Middle-Earth, of the melancholic passing of magic folk from our world. But the narrative is also shadowed by the famous capriciousness of both love and the Fay — a baby, for example, is stolen from Edgewood and replaced with a monstrous changeling. But even here, Crowley does not use dark mischief to raise the narrative stakes so much as to occasion further imaginal overtones, intimations of character transformation that seem to draw something from us as well, as if we are following the footsteps of the young Auberon, who would “court, on long woolgathering rambles, Psyche his soul.”

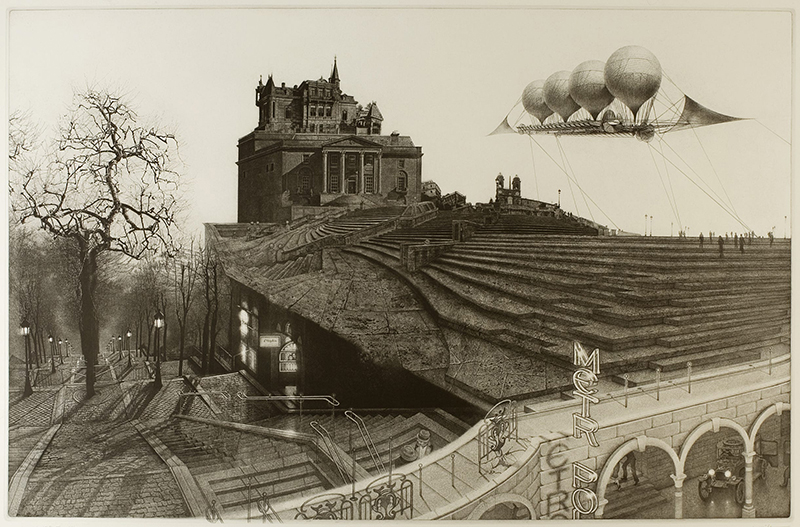

These rambles, it is important to say, do not place in Edgewood’s Arden-like Arcadia. They take place in the City, which provides the stage for far more of the novel than you would have guessed given the story’s initial turn towards the sylvan. Crowley’s 1981 contribution to the budding genre of urban fantasy results in part from the author’s own metabolism of his experience of living in New York City as a young man, experience that is mulched to an even finer degree in Aegypt. But I also suspect that Little, Big’s concern for architecture — at one point even the zodiac is described as the “attic of the gods” — necessitates a deep dive into the crumbling infrastructure of Gotham, which becomes a gritty liminal zone equally as charmed as the ponds and groves that surround Edgewood. We get a dilapidated bohemian farmstead tenement, 1970s-style, but we also get hermetic bike messenger shops, elite illuminati clubs, scruffy Old World bars, and the swampy streets. We also get one of those marvelous locked gardens that pepper Manhattan, a leafy jewel that Crowley transforms into a memory palace along the lines of the ancient ars memoria — the hermetic art of memory that serves, along with Tarot and popular Theosophy, as one of the novel’s crucial esoteric currents.

Crowley’s turn towards the city is also a turn towards the variety of humans that inhabit it, though in its handling of people and cultures of color, Little, Big too appears a bit dilapidated. On the one hand, Crowley bravely if tentatively expands his imaginal realm beyond the northern European, especially into Santeria, Carnival, and Spanish Harlem. We meet a few compelling if minor black characters, some of whom speak in awkward dialect, but Auberon’s great love, the Puerto Rican firecracker Sylvie, does not quite transcend stereotype. And while Crowley rarely turns down the opportunity for a fairy tale wink, that’s probably not a good excuse for naming a diminutive black man who works the farmstead “Brownie.”

Wrestling with this stuff in our trigger times, I thought of the Rolling Stones album Some Girls, which came out in 1978, three years before Crowley’s novel. Like Little, Big, the Stones album is in part a vexed love letter to NYC that also happens to be a masterpiece. Don’t know if you have listened to it lately, but it is also laced with some cringey shit. But if Crowley sometimes fails his urban tribes, he makes a larger imaginal error upstate: pure erasure. At one point, Ariel Hawksquill, a learned mage of the Dame Yates school, speculates that the faeries came “to this new world” around the same time as the Europeans, but were eventually disappointed. “The virgin forests where they hid themselves gradually logged, cities built on the river-banks and lake shores, the mountains mined, and with no old European regard for wood-sprites and kobolds either. . . .” But even less regard was paid to the other-than-human persons who already inhabited those supposedly virgin forests: the crow spirits and hairless bears and horned serpents of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Nations. This is not to chastise Crowley, who more than makes up for this slight in his other fictions, from the minority laborers who star in Four Freedoms to the magnificent Native American episode in his brilliant, dark, late work Ka. It is simply to recognize a missed American opportunity.

And perhaps it is those native tricksters, rather than any settler-colonialist leprechauns, who stand behind one of the most remarkable things about this remarkable edition of a remarkable novel: the shocking concatenation of bad luck, flubs, and foibles that impeded the production of this 40th anniversary edition, which actually turned out to be the 42rd anniversary edition, and which was originally supposed to be the 25th anniversary edition.

I asked Ben Kamm — a Crowley buff, ethnobotanist, and sometimes publisher who gallantly took on overseeing the project’s completion late in the game — to offer a brief resume of these troubles. It was impossible, so vast and twisted was the sticky spider web of woe, involving bankruptcies, strokes, monomaniacal obsessions, corrupted databases, broken arms, dreams, hailstorms, printing errors, disgruntled purchasers threatening to “cast a dark spell” upon the team, and not one but two shipments of slipcases that were simply “lost in transit” as into some new Bermuda triangle emerging in Chinese waters. “Whatever the cause, there have been an uncanny level of mishaps & complications,” Kamm explained. “It has often felt like I’m caught in some vapid enchantment, some fairy farce where I’ve been given an ever renewing task of drudgery, spurred on by the shimmering glamour of ‘an end in sight’!…” But as a mature man of enchantment himself, Kamm sees the paradox of it. “Perhaps the temporal expanse of the project and all the problems that have vexed it were inevitable. Maybe this long, bewildered journey was essential to slowly gather and refine potency — so now, at long last, we have an edition of effervescent wonder. It’s a comforting thought at least!”

Along with Neil Gaiman and a few others, I donated funds last year to see the project through. I make no profits from any sales, and the entire publication is effectively a fantastical charity project at this point — even Ben is working for peanuts. My contribution allowed me to honor one of my favorite living authors, and to support the birth of a truly special object into the world of literature, not to mention into my own hankering hands. I love physical books, and fine editions of modern phantasy — Beckford, Machen, Dunsany, Hodgson, Tolkien, Lovecraft, Ashton Smith, Howard, Peake, Le Guin, Wolfe, Ligotti, Crowley — are among my most adored.

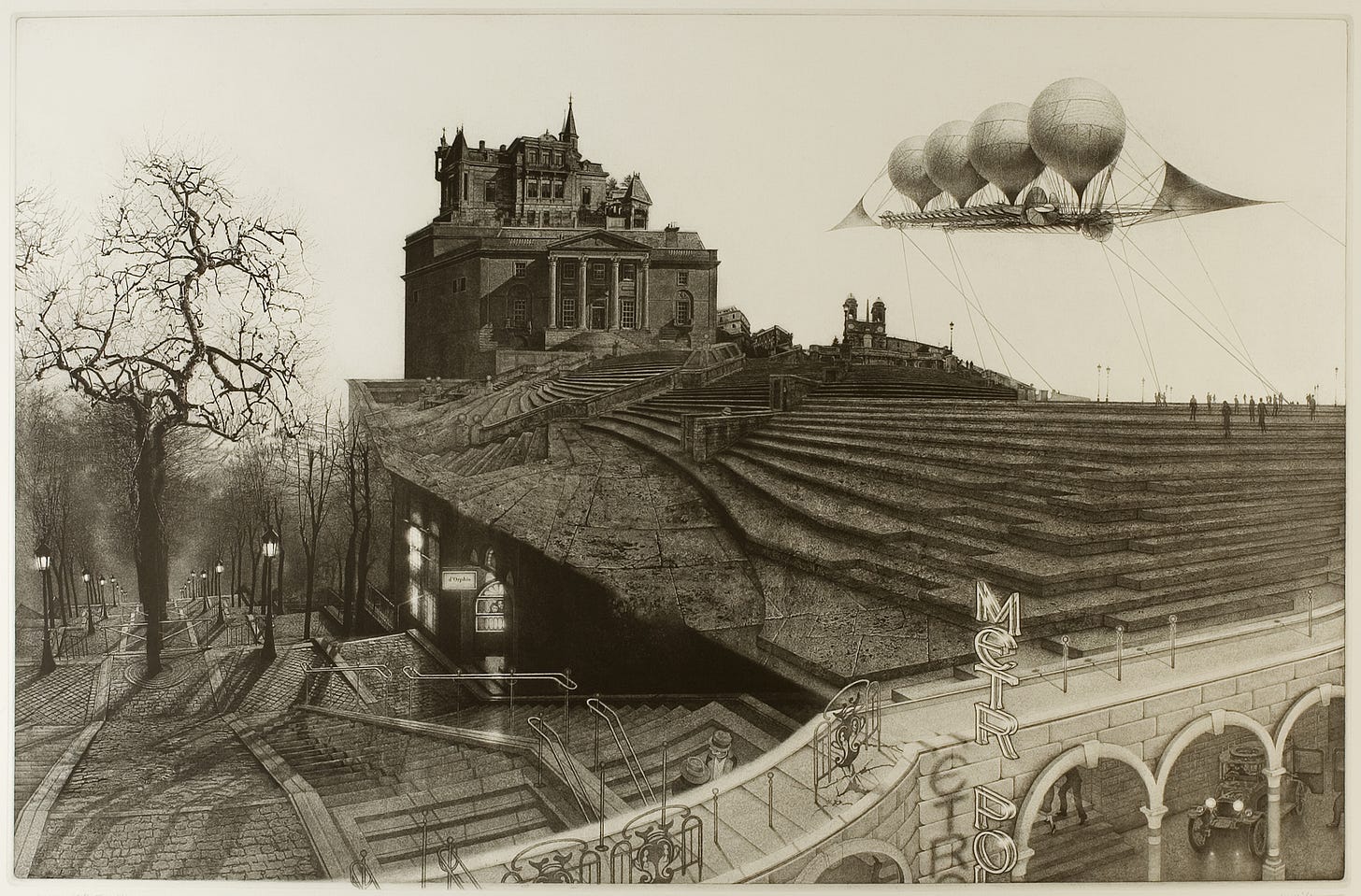

Having now reread the book in its fullest and finest form, which also presents Crowley’s final and preferred version of the text, I can promise it was worth the wait. There is a strange magic in this edition, largely because of Peter Milton’s art and how it interacts with the text. Before this I had not heard of Milton, a colorblind American artist now in his 90s. His black-and-white etchings, at once photorealistic and phantasmagoric, hit all the important notes of this novel — architecture, memory, eros, myth, but especially how the daemonic and the ordinary intertwine to structure our enchanted modernity. And it is a structure — a crisp architecture that follows a surreal logic, like a house of mirrors or a roadside mystery spot, or Milton’s sublime blueprints. Moreover, the animist enchantment that infuses Milton’s work is Art Nouveau rather than medieval or even Victorian.

The kinda spooky thing here is that Milton was not responding to Little, Big directly. Project mastermind and editor Ron Drummond, along with designer John Berry, just drew the book’s illustrations from Milton’s already existing work, often selecting small details from his large dense pieces to support appropriate moments in the text. “Good shot!” we read as Doc and Smoky hunt, and then we face two silhouettes unfolded from one of Milton’s vast pictures, two tweedy men in caps shooting at flying geese. How did he know? Drummond’s almost Ouija-board worth work with the illustrations, while occasionally excessive, is haunted with rich serendipity, and continually stages the uncanny sense that Milton was illustrating Little, Big in advance.

Besides, where the Fay take, they also give. In addition to the hardcover Trade edition of the 40th edition, slipcased Numbered and Lettered versions of the text were prepared as well. The Numbered edition were limited to 300 copies, which all pre-sold by 2009. Since that time, every aspect of the production magnified and the edition is now longer and much more lavishly illustrated than what was originally advertised to buyers. For years the publisher fielded requests for additional copies. Then it was discovered that Drummond had produced extra sheets signed by the author, the artist, and Harold Bloom before the latter died in 2019. When production finally commenced in late 2021, these extra sheets were bound into books, thereby increasing the Numbered edition from 300 to a total count of 365.

I don’t want to end this essay with an infomercial, but I suspect the book nuts of the Burning Shore might want to snap up one of these dream tomes. Until the Equinox — September 21 — the code “littlebig40” will get you 10% off any two items on Deep Vellum’s online store. Consider these links and codes a wink and a lure, a rabbit track in a strange literary landscape where “the further in you go, the bigger it gets.”

Upcoming Events

• On Sunday, September 15, starting at 1 pm, I will host Sound Practice, the first in an occasional series of Sense Gates workshops on sensory awareness at the Berkeley Alembic. For this gathering, I will be joined by the musician and mad field recordist Sam Plattner, and we will focus on the contemplative and aesthetic practice of listening – to sounds, to music, to the environment, to the Void. I’ll start out talking about sacred sound in world mystical traditions, including the extraordinary teachings in the Surangama Sutra. We will link these practices to more experimental and aesthetic approaches to “deep listening,” which will be keyed to a variety of manipulated soundscapes, drones, and musical tracks drawn from the spiritual avant-garde.

At 4pm, Sam will present Hidden Vistas, an extended sound collage of subsurface field recordings that reveal the otherwise inaccessible resonances and rhythms residing within our urban environments and infrastructure. All of the source material was recorded with geophones, and have been composed, in both manipulated and unmanipulated form, into a sixty-minute sequence exposing the inner vibrational lives of the components of our built environment at all scales, from massive suspension bridges to washing machines. A Sound Practice ticket gets you in for free, or you can attend the concert separately.

Both events are part of Alembic’s new 3RD EAR series of musical and sound events. 3RD EAR will explore ambient soundscapes, field recordings, experimental electronica, cosmic drones, sonic manipulations, and sacred improvisations. Hearing is a thing that just happens, but listening is a practice: a way of exploring and meditating on sensation, mind, and the vibratory cosmos around and inside us us.

• On Tuesday, September 24th, at 6pm, I will be in conversation with the artist Trevor Paglan at the Altman Siegel gallery, which is hosting Paglan’s latest show, a collection of UFO-haunted photographs called CARDINALS. Paglan is not your typical gallery artist dabbling in the Weird, but one of the most subtle and unnerving scryers of the military-technological-paranormal complex. He has photographed secret military bases, tracked classified satellites and unknown objects in earth orbit, led underwater tours of internet infrastructure, and launched sculptures into space. Our chat will occur in conjunction with the screening of Paglan’s film Doty, a profile of a notorious Air Force intelligence office and artful trickster involved in UFO disinformation campaigns. More info.

Appearances

• You have probably had enough of Blotter by now, but Jon Wilson of the Chambers Project — a top-notch visionary art gallery tucked into the foothills of California’s Gold Country — whipped up this sweet video of Mark and I getting into the pudding at the gallery. The video finely captures the goofy repartee that Mark and I developed over the years of research and hanging out.

• It’s been many moons since I first spoke to the indefatigable Steve Paulson, host of NPR’s (and Wisconsin Public Radio’s) long-running radio show To the Best of Our Knowledge. Recently Steve put together Luminous, a terrific series of psychedelic-themed interviews and discussions. Besides featuring a number of good buddy-peers (Mike Jay, Katherine MacLean, Brian Muraresku), Steve also got me on the horn for a chat. Last month, Steve also published a fine article on psychedelics in Nautilus, which refreshingly focused on philosophical, mystical, and ontological questions rather than the usual therapy talk.

• The TechGnosis Collective is the shared project of three artists scattered across the UK and Europe who were inspired by my old tome. Reading their short manifesto, I am pleased to note that these technonauts are keeping at least one foot firmly planted in and on Terra. “Our mission is to explore the intricate interplay between conscious digital navigation, spiritual practice, and the preservation of humanity and the human experience within the ‘more than human world’.” Bonne chance!

• I recently appeared in the bizarre imagination of Adam Genesis, a comics artist from North Carolina who runs the Adam Genesis Art Universe Channel on IG and YouTube. E8 Comics is Adam’s independent line; its first issue is a chess horror story, in which a Grandmaster is summoned by a dead Bobby Fischer to play chess in another dimension on “Halloween Knight.” I love my expression here, which seems to suggest that, whatever clever thing I am saying, it has become abundantly clear that I am now in way over my head.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though for now I will not be offering any subscriber-only content. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.