The Untold Story of an Acid Medium

Available from The MIT Press, April 30, 2024

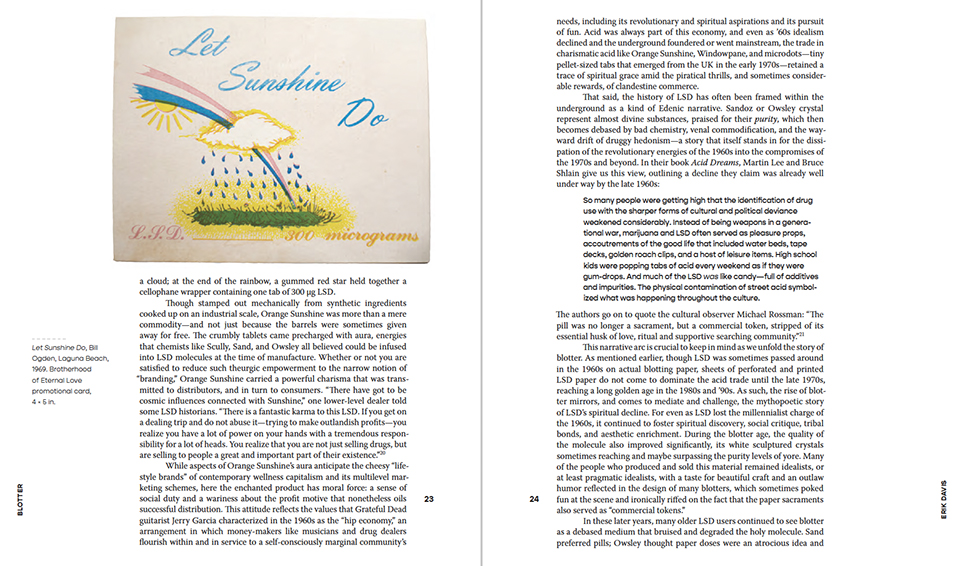

Blotter by Erik Davis is the first comprehensive written account of the history, art, and design of LSD blotter paper, the iconic drug delivery device that will perhaps forever be linked to underground psychedelic culture and contemporary street art. Created in collaboration with Mark McCloud’s Institute of Illegal Images, the world’s largest archive of blotter art, Davis’s boldly illustrated exhibition treats his outsider subject with the serious, art-historical respect it deserves, while also staying true to the sense of play, irreverence, and adventure inherent in psychedelic exploration.

Excerpted in the Paris Review:

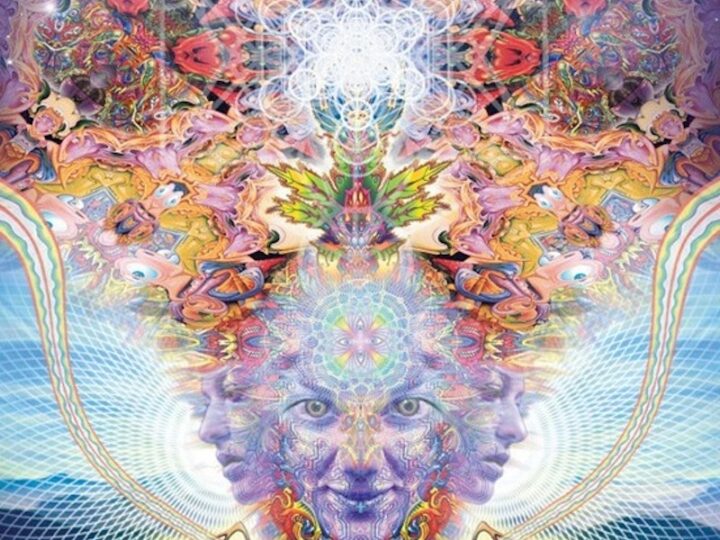

“LSD’s particular and peculiar relationship to technical mediation is historically situated. First synthesized in 1938 but not tasted until 1943, acid is essentially a creature of the postwar era. As such, it enters the human world alongside an explosion in consumer advertising, the rapid development of electronic and digital media, new polymers, and a host of increasingly cybernetic approaches to the social challenges of control and communication. For many of its early enthusiasts, acid was like a cosmic transistor radio. As Lars Bang Larsen writes, “Hallucinogenic drugs were often understood as new media in the counterculture: only machinic and cybernetic concepts seemed sufficient to address vibrations, intensities, micro speeds, and other challenges to human perception that occur on the trip.” To paraphrase Timothy Leary, LSD seemed to “tune” the dials of perception, altering the ratios of the senses, “turning on” their associational pathways and gradients of intensity. These vibrating modulations in turn catalyzed transpersonal peaks that bloomed as insights, revelations, satoris, “groks.”

The actor and author Peter Coyote, who was a member of the visionary Diggers collective in the Haight during the sixties, wrote that ingesting LSD “changed everything, dissolved the boundaries of self, and placed you at some unlocatable point in the midst of a new world, vast beyond imagining, stripped of language, where new skills of communication were required . . . [because] everything communicated in its own way.” Similarly, Marshall McLuhan, the pop media prophet of the era, told Playboy that LSD mimes the “all at onceness and all at oneness” of the new electronic media environment. All this set the stage for a kind of technical mysticism that recalls the media theorist Alexander Galloway’s notion of “iridescent” mediation: “communication as luminous immediacy.” Alan Watts, commenting on the question of how often to take LSD, also turned to media metaphors, arguing that when you get the message, you hang up the phone.

“But what if the medium is the message? In other words, what if the self-referentiality of acid consciousness—which can nest chains of Harlem cartoonists like Russian dolls, or loop the act of seeing back into the seer—also absorbs the material medium that delivers the LSD to your nervous system in the first place? Of course, the primary medium of this consciousness is the LSD molecule itself. But unlike macroscopic drugs like cannabis, LSD is so small and so powerful that its consumption almost always requires an inert housing—the water, tablets, sugar cubes, bits of string, or pieces of paper that transport the drug from manufacturer to tripper. In the law, this vehicle is described as the “carrier medium,” an object impregnated with drugs, one that can be sold, seized, presented as evidence, and dissolved into the hearts, minds, and guts of consumers.

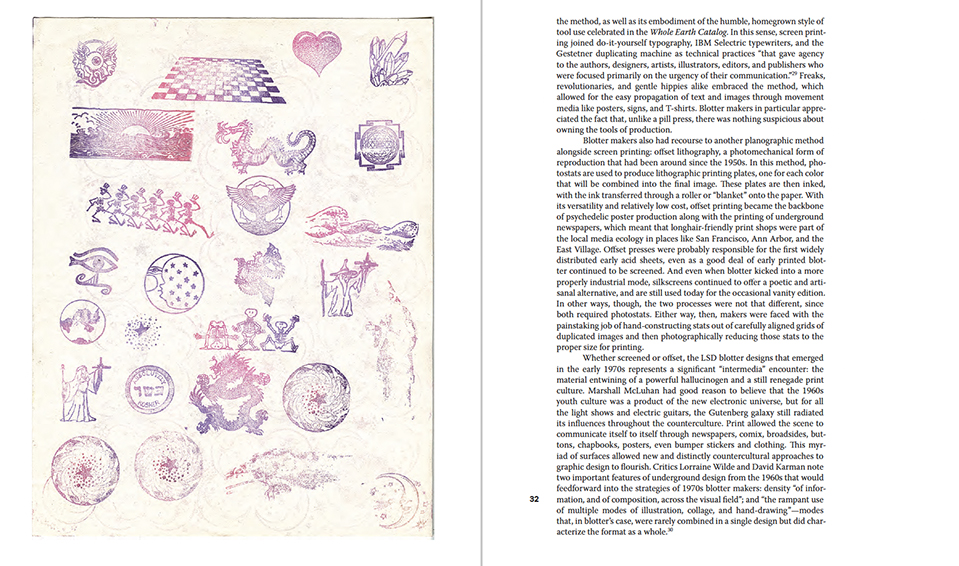

“When you print images onto a paper carrier medium, you are adding another layer of mediation to an already loopy transmission. Hence, a meta medium, a liminal genre of print culture that dissolves the boundaries between a postage stamp, a ticket, a bubble gum card, and the communion host. This makes blotter a central if barely recognized artifact of psychedelic print culture, alongside rock posters and underground newspapers and comix, but with the extra ouroboric weirdness that it is designed to be ingested, to disappear. Blotter is the most ephemeral of all psychedelic ephemera. It is produced to be eaten, to blur the divide between object and subject, dissolving material signs and molecules into a phenomenological upsurge of sensory, poetic, and cognitive immediacy.”