Lee Perry on the Mix

Having abandoned the Jamaican tropics for the snowy peaks of Switzerland, the legendary reggae producer Lee Perry — aka Scratch, the Upsetter, the Super-Ape, Pipecock Jackson, Inspector Gadget, the Firmament Computer, and a cornucopia of other monikers and aliases — now makes his home in one of the quietest corners of Europe. It’s an odd but somehow fitting environment for Perry — not because precision clocks and banks have much to do with the intense, spooky, and profoundly playful records he’s known for, but because Lee Perry had always been something of a stranger in a strange land.

Though still capable of turning out brilliant tunes like “I Am a Madman” and “Secret Laboratory (Scientific Dancehall),” Perry’s current output pales next to the pivotal music he made in the 1960s and 70s, especially the Rastafarian psychedelia he cooked up at his Black Ark studios in the mid 1970s. During that incredibly prolific period (he produced over 1000 sides in ten years), Perry fused his eccentric spiritual vision with powerful protest music, made some of the most surreal experiments with dub reggae, and sculpted the first (and arguably greatest) records by Bob Marley and the Wailers. Utilizing low-tech studio equipment with a brilliance and panache that continues to astound record producers and music fans today, Perry earned a place alongside Phil Spector and Brian Wilson as a visionary studio wizard who transformed pop music production into an art form all its own.

These days, it’s Perry himself who is the work of art. He appears in public festooned with pendants, parts of machines, bits of tape, patches, buttons, and reflective mirrors. Everywhere he goes, it seems, he leaves a collage of scribbled notes, cryptic graffiti, scrap-metal idols, paintings of lions and food. Responding to interviewers with a flurry of rhymes, riffs, and puns, Perry turns innocent questions into a cosmological launching pad, revealing what John Corbett describes as “a world of hidden connections and secret pacts:”[1] multinational conspiracy theories, Old Testament prophecies, scatological rants, Rastafarian poetry, incantations of the Jamaican folk witchcraft known as obeah.

All this takes Perry to the edge of madness–at once his apparent mental instability and his intensely performative, almost shamanic, relationship with the chaos of creation. As Corbett points out, New World black culture has long linked the rhetoric of madness with excellence and innovation — musicians especially are praised for being “out of control,” “crazy,” “wild.” While Perry’s hermetic language games and comic-book metaphysics certainly owe something to his daily intake of what one observer described as an “inordinate amount of high quality herb,” his mischievous irony also shows all the signs of the trickster incarnate. Even his “madness” may be a trick. Some colleagues report that when it’s time to talk business, Perry drops the loopy patois and cuts to the chase; the head of Heartbeat Records says that he “plays fool to catch wise.”

Perry is also a kind of Caribbean techgnostic, deploying his almost supernatural imagination within the technological context of the modern recording studio. With its soundboards, mics, effects processors, and multiple-track tape manipulations, the studio is clearly a kind of musical machine. However passionate and spontaneous pop songs may sound on the radio, the music itself is as much a product of engineering as of performance. Despite their crude equipment, reggae producers like Perry, King Tubby, and Bunny Lee became artists in their own right — especially when it came to dub, the instrumental offshoot of reggae concocted entirely in the studio.

Modern Jamaican music begins with signals and machines. In the mid to late 1950s, when a diminutive Lee Perry first arrived in Kingston from the sticks, the popularity of mento — an upbeat and topical Afro-Caribbean music similar to Trinidadian calypso — was giving way to a rage for American rhythm&blues. At that time, powerful and increasingly independent U.S. radio stations were turning away from the old national radio networks towards an inexpensive and popular alternative: DJs playing records for local markets. For the first time, signals were beamed directly at African-American communities. And when the weather was right, Jamaican kids churning through their radio dials would tune into Southern radio stations, and they went especially wild for the gritty, saucy sounds of New Orleans R&B.

From this enthusiasm sprang Jamaica’s “sound systems”–mobile discos that would invade halls and auditoriums with high-wattage amplifiers, turntables, DJs, imported American vinyl, and massive speaker stacks. Besides transforming the invisible figure of the radio DJ into a performer, sound systems also gave their American grooves an unmistakable Jamaican twist by severely pumping up the bass. Amplifying their woofers to the max, sound systems transformed R&B’s low end into a veritable force of nature — the kind of bass that does not just propel or anchor dancers but saturates their bones with near cosmic vibrations.

In the late 1950s, the sound systems were ruled by a host of colorful characters like Duke Reid, who lorded over his “Treasure Isle” dances with a cartridge belt, an enormous gilt crown, and a shotgun that he would occasionally brandish when the competition between sound systems boiled to a head. These fierce rivalries had an obviously economic edge, but their roots lie in the competitive performance traditions of many West African cultures. The fight over customers waged by sound system producers was also a style war, their fabricated alter egos, costumes, and elaborate verbal boasts taking on an almost ritualistic — yet constantly reinvented — dimension. Such style wars show up in various guises across the African diaspora, from the taunts and “dises” of rappers to the yearly carnival competitions of Trinidad and Brazil, when various roving “bands” try to top each other and woo the crowd with music, dance, and costume. As Lee Perry said, “Competition must be in the music to make it go.”[2]

Jamaica sound systems were unique in that this premodern, almost “tribal” competition was played out across the modern landscape of mechanically reproduced recordings. Rivalries were not so much a “battle of the bands” as a kind of technological and information warfare: who had the heaviest bass, who had the hottest records. In the 1950s, many DJs considered their imported sides exclusive, buying up all available copies of a new record or flying to the States to buy fresh discs. Spies would show up at rival sound system parties, peering at the record labels over the DJ’s shoulder, and in response, DJs would scratch off labels or stick on false ones.

Here was an environment where a trickster like Lee Perry could thrive. Rejected by Duke Reid, who was spooked by something in his eyes, Perry went to work for Clement “Sir Coxone” Dodd’s rival “Downbeat” system, where he served as a talent scout, runner, gofer and occasional monkey-wrencher. Perry told one interviewer how he once put out the rumor that a certain fellow was selling really “dread sides.” Duke Reid went and bought them all without listening to them first. “And they all old stuff, duds!” For such antics, Duke’s men once stormed a Downbeat party and started punching people out, knocking Scratch unconscious.

With the decline of R&B in the US market and Jamaica’s independence from Britain in 1962, homegrown mutations begin to dominate sound systems. The most prominent was ska, a hopped-up, horn-driven and very danceable music whose intense offbeat punches one apocryphal story attributes to the interference patterns that sliced up radio signals from the States. Perry started churning out ska at Coxone’s Studio One, cutting edgy and punchy songs like “By Saint Peter” and “Chicken Scratch”the latter earning “Scratch” his most lasting nickname.

Perry always had something of a persecution complex, and frequently turned on former friends and business partners. In part this reflects the cut-throat environment of the Jamaican record industry, where what Dick Hebdidge describes as “tough and wily” producers often acted like pirates. But with Perry — who once knowingly sold thousands of copies of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Soul Revolution II with the wrong record inside — one can also see the mischievous and occasionally malicious hand of the trickster. Perry certainly incorporated personal attacks into his “mad” persona: a number of Perry songs badmouth former associates or mumble threats concerning obeah men, while the 1985 cut “Judgment Inna Babylon” accused the head of Island records of literally being a vampire.

After splitting acrimoniously from two top studios, Perry started up his own Upsetter studios in 1968, and soon released a tune attacking his former boss Joe Gibbs. Anticipating today’s sampling craze, “People Funny Boy” included a crying baby in the mix in order to show how “upset” Perry was. But “People Funny Boy” also slowed down and reshuffled the usual rock steady rhythm, a bass-heavy rhythm that by the late 1960s had replaced the more simplistic beats of ska. In doing so, Perry helped engineer the beat that would come to dominate Jamaican music in the 1970s: reggae.

Though reggae recalls the relaxed rhythms of the old secular mento music, it has a meditative sustenance that some compare to religious church music or the Nyabhingi drumming of Rastafarian gatherings. Perry claims he just wanted to top his rivals with a new sound that had a “rebel bass” and a “waxy beat, like you stepping in glue.” But the inspiration he cites was a Pocomania revivalist church he passed one night after drinking some beer:

(I) hear the people inside make a wail and say, ‘let’s make a sound fe catch the vibration of the people!’ Them was in the spirit and them tune me spiritually. That’s where the thing comes from, ‘cos them Poco people getting sweet.[3]

Pocomania was one of a number of independent revivalist churches that sprung up during Jamaica’s “Great Awakening” of the 1860s, churches which exuberantly fused African and Protestant performance styles, images, and traditions. Pocomania leaned to the African side of things, its Pentecostal-style services owing an obvious debt to African possession ceremonies. Worshippers would dance counter-clockwise to powerful drums while breathing very deeply; this “trumping” would sometimes brings on possession — the “little madness” that lent the church its name.

So at the root of the reggae we have a little Lee Perry madness, a tale of catching vibrations and tuning into spiritual trance. But Perry played a far more direct role in developing the religious dimension of reggae when he began writing and recording songs with Bob Marley and the Wailers. The Wailers were a talented Studio One group known for sweet vocals, American soul covers, and a rebel stance. As residents of Trenchtown, Kingston’s most notorious slum, the Wailers were associated with Jamaica’s “rude boys”–tough, poor and restless urban kids who flaunted authority (and sometimes the law). By the late 1960s, Marley and the Wailers were also turning toward Rastafari, a rebellious and extraordinary religious counter-culture that wove together Black Pride, an “Ethiopian” reworking of Biblical tenets, and a prophetic opposition to “Babylon”, the Rastafarian archetype of the modern nation-state, with its police, economic injustice, and corrosive lifestyles. Perry collaborated with the future superstar on some of his earliest and most powerful songs, tunes that mixed sharp social commentary (“a hungry mob is an angry mob”) with an ardent yearning for Jah.

Since the trappings of Rastafari have been packaged by the international reggae market and embraced, often superficially, by legions of white college kids, punks and hippies, we should scratch a bit beneath the surface of this vital New World religion. Like America’s Black Muslims, the roots of Rastafari lie with the ethno-religious worldview sculpted by the Jamaican reformer Marcus Garvey. Founding the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914, Garvey attempted to uplift and unite New World Africans by emphasizing the superiority of the black man and the glories of African civilization. Anticipating the Afrocentricity of today, Garvey preached the love of a black deity, a “God of Ethiopia.” He also called for repatriation to the motherland, even founding a shipping and transportation company called the Black Star Line with the intention of transplanting New World blacks to Liberia.

But Garvey never visited Africa, and his vision of Ethiopia had more to do with the visceral power of the religious imagination than with the concrete geo-political realities of an African continent struggling with the ravages of European colonization. By Garvey’s time, Black Christian churches had already embraced the Biblical Ethiopia as a potent allegorical image of spiritual fulfillment, the millennial “Zion” that offered both a redemptive future and a glorious origin. Though Garvey’s call for repatriation offered black folks an apparently concrete solution to the nightmare of abduction and slavery, the Africa he offered was a landscape of religious desire — a virtual world.

When Garvey quit Jamaica for the United States, he reportedly left his followers with this potent prophecy: “Look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King; he shall be the Redeemer.” In 1930, when Haile Sellasie, aka Ras Tafari, was installed as King of Ethiopia, Garvey’s Jamaican followers believed they had found their living god, and Rastafari was born. Ethiopia has been Judeo-Christian longer than most nations on the earth, and Sellasie’s bloodline was supposed to stretch back to King Solomon, his official titles like “King of Kings” and “Lion of the Tribe of Judah” drawn directly from Biblical prophecy. Reading their own political and cultural desires into these Rorschach blots of messianic allegory, Rastafarians transformed the distant king into the Book of Daniel’s bearded Ancient of Days, “the hair of whose head was like wool, whose feet were like unto burning brass.”

As with Elijah Mohammed’s Black Muslims, the early Rastafarians also racialized their theology. As the religious scholar Leonard Barrett explains, “the Whites’ god is actually the devil, the instigator of all evils that have come upon the world, the god of hate, blood, oppression, and war; the Black god is the god of ‘Peace and Love.'”[4] Though contemporary Rastafarians speak of “One God” more than a black god, it’s important to note the loosely “gnostic” elements here. Along with the Manichaean tension between the two gods, we have the old gnostic vision of a dark tyrant god who rules over souls in exile. According to Barrett, the early Rastafarians believed that slavery was initially a punishment for their sins, but that “they have long since been pardoned and should have returned to Ethiopia long ago.”[5] Only the evil trickery of the slavemaster prevents them from returning to the heavenly home where their living King awaits.

Both the separatist practices and the emotional core of Rastafarian life can be traced to this deeply felt sense that the Rastaman is in Babylon, but not of it. As Silja Joanna Aller Talvi writes, “From the Rasta’s perspective, the whole world is full of Babylon, and Babylon systems are constantly seeking to oppress (or ‘downpress’) and exploit the African.”[6] Rejecting the authorities of this world, Rastafarians attempt to create a separate “God-like culture,” in part by embracing the organic world of nature as a kind of anti-modern alternative to Babylon. Most Rastafarians are vegetarian, eat only “ital” (fresh and healthy) food, and reject commercial products and medicines; many also grow their hair in dreadlocks, the “natural” shape of long kinky hair that’s washed but neither combed, cut or treated. Though Rastafari was spawned in the slums, many “locksmen” abandoned the urban hustle for lives as fisherman or simple farmers; those who remained were shunned by most respectable Jamaicans as “Blackhearts” or boogiemen.

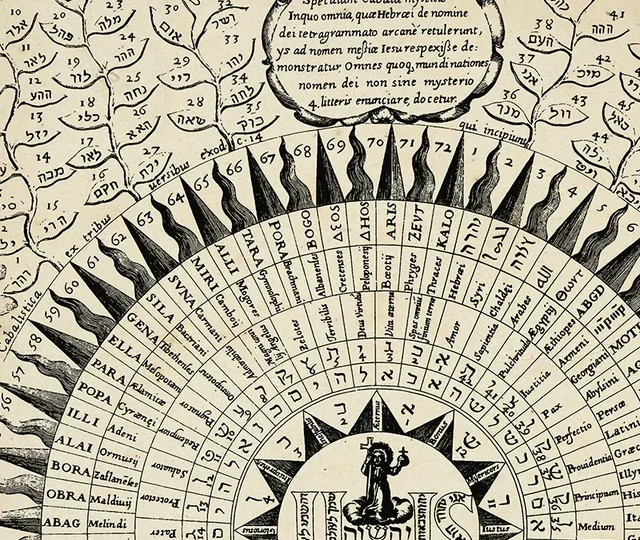

Though the movement had a handful of charismatic leaders early on, and today includes organized sects like the Twelve Tribes of Israel and even members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, most Rastafarians abhor institutions, grounding their faith in their own direct participation in the divinity and holiness of Jah. As Ras Sam Brown said, “The Rastafarians movement is not a movement with a central focus.”[7] Somewhat like the early gnostic sects, most Rastafarians also believe that the Bible is an intentionally “mistranslated” document whose scrambled signals must be read selectively and allegorically in the light of personal revelation.

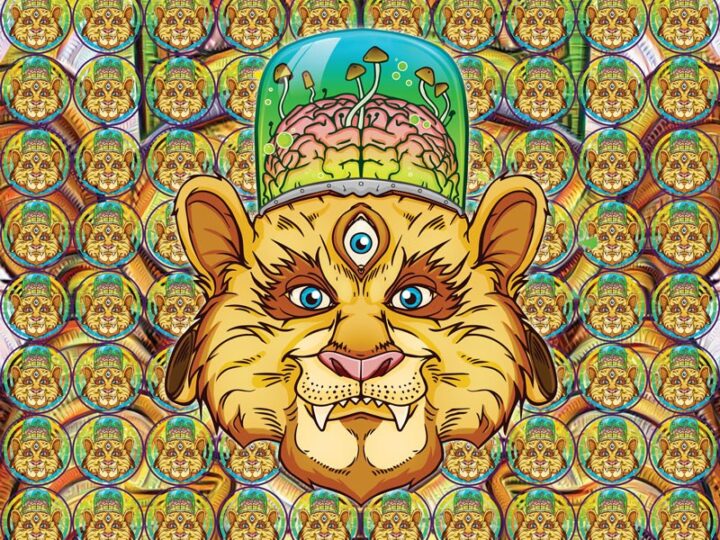

One of the brightest guiding lights of Rastafari is the flame of the “chalice,” stuffed with sticky marijuana buds that crackle during inhalation. Addressing the sacramental use of marijuana among Rastafarians, Barrett argues that “the real center of the movement’s religiosity is the revelatory dimensions brought about by the impact of the ‘holy herb.'” Long a Jamaican folk medicine, marijuana was probably introduced to the island by indentured East Indian Hindus, who gave the plant its popular name “ganja” and may have inspired its religious use (many of India’s wandering mendicant “sadhus” also wear dreadlocks, eat vegetarian food and smoke hashish in a religious context). For all their glassy, bloodshot stares, it’s wrong to think of Rastafarians as “stoners”; hardcore adherents consume ganja as a sacrament and rarely use other drugs or alcohol. One Rasta explained the role of ganja in strongly gnostic terms, though it is a gnosticism shot through with Rastafari’s powerful social consciousness:

“Man basically is God but this insight can come to man only with the use of the herb. When you use the herb, you experience yourself as God. With the use of the herb you can exist in this dismal state of reality that now exists in Jamaica…When you are a God you deal or relate to people like a God. In this way you let your light shine, and when each of us lets his light shine we are creating a God-like culture.”[8]

Barrett explains that to the Rastafarian, “the average Jamaican is so brainwashed by colonialism that his entire system is programmed in the wrong way…To rid his mind of these psychic forces his head must be ‘loosened up,’ something done only through the use of the herb.”[9] As one Montego Bay “dread” described the plant ally, “It gives I a good meditation; it is a door inside.”[10]

Of course, music can also serve as a door inside. The chants and “churchical” beats of traditional Nyabhingi drumming played a vital role in Rastafarian “Grounations,” communal celebrations notable for their ital feasts, ganja smoking, and mystical theologizing. Though not directly influencing the reggae beat, Nyabhingi’s meditate rhythms did infuse reggae with the sense that music can help “loosen up” the shackles of everyday consciousness, sparking the inner light of righteous contemplation.

Bob Marley was not the first musician to bring Rastafari into Jamaican dance music, but with earthy hymns like “400 Years,” “African Herbsman” and “Duppy Conqueror”, he and Perry injected folkloric nectar into their spare and sinewy arrangements with divine panache. Like American soul, but even more so, reggae would rapidly become a commercial product of the popular recording industry that nonetheless derived much of its power and appeal from a deeply religious set of images and desires. By no means was all reggae Rastafarian, but with “message” producers like Perry leading the way, Jamaica would produce perhaps the juiciest spiritual protest music of the 1970s. By the time of his death at the end of the decade, Bob Marley would rear his lionlike mane over a global stage as the first Third World pop star, his plaintive “redemption songs” spreading the message of Rastafari across a shrinking planet desperate for spiritual heroes.

Though Marley’s records were cleverly packaged by Island’s Chris Blackwell for a white rock audience, much of their appeal derives from the unshakable authenticity of the man, the righteous integrity he shared with many of reggae’s stars. In the ’70s, the cries and beats of Jamaica’s new “roots music” seemed to spring, not only form the hearts of suffering black folks, but from the island soil itself. You could hear these roots in the music’s moist guitars and stoned pace, its “natural mystic” vibrations, and its crunchy, spongy beats (Marley called it “earth-feeling music”). And you could feel the roots as well in the virtual Africa that hovered on the messianic horizon of the music, an ancient motherland and future kingdom built from the gnostic longings of souls exiled in the brave New World of Babylon.

But dub music, reggae’s great technological mutant, is a pure artifact of the machine, and has little to do with earth, flesh, or authenticity. To create dub, producers and engineers manipulate preexisting tracks of music recorded in an analog, as opposed to digital, fashion on magnetic tape (today’s high-end studios encode music as distinct digital bits rather than magnetic “waves”). Dubmasters saturate individual instruments with reverb, phase, and delay; abruptly drop voices, drums, and guitars in and out of the mix; strip the music down to the bare bones of rhythm and then build it up again through layers of inhuman echoes, electronic ectoplasm, cosmic rays. Good dub sounds like the recording studio itself has begun to hallucinate.

Dub arose from doubling, the common Jamaican practice of reconfiguring or “versioning” a prerecorded track into any number of new songs. Dub calls the apparent “authenticity” of roots reggae into question because dub destroys the holistic integrity of singer and song. It proclaims a primary postmodern law: there is no original, no first ground, no homeland. By mutating its repetitions of previously used material, dub adds something new and distinctly uncanny, vaporizing into a kind is doppelgnger music. Despite the crisp attack of its drums and the heaviness of its bass, it swoops through empty space, spectral and disembodied. Like ganja, dub opens the “inner door.” John Corbett even links the etymology of the word “dub” with duppie (Jamaican patois for ghost). Burning Spear entitled the dub version of his great Marcus Garvey album Garvey’s Ghost, and Joe Gibbs responded to Lee Perry’s production of Bob Marley’s “Duppie Conqueror” with the cut “Ghost Capturer.” Perry described dub as “the ghost in me coming out.”[11] Dub music not only drums up the ghost in the machine, but gives the ghost room to dance.

Though he became one of its most surreal experimenters, Lee Perry did not invent dub reggae. That honor goes to Osbourne Ruddock, aka King Tubby, an electrical engineer who fixed radios and other appliances in Kingston in the 1950s and who built his own sound system amplifiers to get the big bass sound. A musical genius, Tubby was also a gearhead, a tinkerer, an experimental geek. After discovering that he could remix the backing track of a popular tune into a new piece of music, Tubby played these “dub plate specials” to enthusiastic crowds at his Home Town Hi-Fi dances, where Tubby would stand behind his customized mixing console, tweaking the beats on the fly while the DJ U Roy “toasted” over the rhythms.

Jamaican trends spread like wildfire, but Tubby stayed ahead of the dub game by working with top producers like Bunny Lee and Lee Perry while endlessly tinkering with what Prince Buster called the “implements of sound.” Tubby constantly toyed with his four-track console, jury-rigging echo delay units and created sliding faders that allowed him to bring tracks smoothly in and out of the mix. He also just played tricks with the machine, generating his famous “Thunderclap” sound by physically hitting the spring reverb unit, or using frequency test tones to send an ominous sonar through the depths of dub’s watery domain. Though Tubby gave his records names like Dub from the Roots and The Roots of Dub, he had genetically engineered those roots into wires.

However, dub did restore the roots of reggae’s own “dread ridims” by conjuring the ghost of West African polyrhythms via the unlikely mediation of the machine. Though modern Jamaican dance music adheres to the same 4/4 beat that drives most popular music, reggae was already unusual in accenting the second and fourth beats of the measure and in “dropping” the initial beat, all of which produced the music’s unmistakable pulse. By anchoring the beat with the bass guitar rather than the drum kit, reggae also freed up the drums to explore subtler and more complex percussive play. As Dick Hebdidge points out, by the end of the ’70s, drummers like Sly Dunbar were playing their kits like jazz musicians, improvising on cymbals, snares and tom toms to “produce a multi-layered effect, rather like West African religious drumming.”[12]

Dub launched these already tangled ridims into orbit, using technological effects to thicken the beats and to stretch and fold the passage of time. Besides stripping the music down to pure drums and bass and adding raw percussion, Dubmasters introduced counter-rhythms by multiplying the beats through echo and reverb while splicing in what the producer Bunny Lee called “a whole heap a noise.” And by abruptly dropping guitars, snares, hi-hats and bass in and out of the mix, they created a virtual analog of the tripping, constantly shifting effects of West African polymetric drumming. Though the hallucinogenic effects of dub are usually attributed to its “spacey” effects and the role of ganja in both its production and consumption, the almost psychic pleasures of the music also arise from its silly putty beats and their ability to yank the rug out from under your deeply ingrained sense of a central organizing rhythm.

By giving flight to the producer’s technical imagination, dub sculpted a sort of science-fiction aesthetic alongside reggae’s crunchy Africentric mythos. As Luke Erlich wrote, “If reggae is Africa in the New World, dub is Africa on the moon.”[13] Just look at the cover art: Mad Professor’s Science and the Witchdoctor sets circuit boards and robot figures next to mushrooms and fetish dolls, while Scientist Encounters Pac-Man at Channel One shows the Scientist manhandling the mixing console as if it were some madcap machine out of Marvel comics. It’s important to note that in Jamaican patois, “science” refers to obeah, the African grab-bag of herbal, ritual and occult lore popular on the island. And as Robert Pelton points out, the figure of the scientist is not so distant from the spirit of the trickster that runs throughout this tale: “Both seek to befriend the strange, not so much striving to ‘reduce’ anomaly as to use it as a passage into a larger order…like the scientist, the trickster always yokes just this world to a suddenly larger world.”[14]

And Lee Perry continued to serve as reggae’s trickster king. Not only did he make some remarkably spare and intense forays into dub, but he applied dub’s spectral aesthetics to the rest of his increasingly surreal, popular, and unorthodox productions. In 1974, the producer built Black Ark Studios, destined to become the launching pad of reggae’s most surreal and moving tunes. A year later, he acquired a demo version of a unique phaser from the States; using it alongside with a Roland Space Echo, a primitive drum machine with loads of reverb, Perry whipped up multi-layered cakes of noise, polyrhythms, ghostly percussion and sounds lifted from other records. He took advantage of anomalies, especially of his limited 4-track. As the producer Brian Foxworthy explains, Perry would fill up the four available tracks and then mix them onto a single track on another machine, freeing up three tracks to add more effects and percussion. Like xeroxing a xerox, each go-around added more noise to the signal, yet the very “decay” of the signal adding a moist, organic depth to the music. It’s a classic example of the trickster’s mischievous relationship to disruption and chaos. As Foxworthy told Grand Royal magazine, “Tape saturation, distortion and feedback were all used to become part of the music, not just added to it.”[15]

Black Ark was more than Jamaica’s most innovative studio; it was the visible vehicle of Perry’s passionate otherworldly imagination. It’s walls were covered with portraits of Selassie, magazine collages, lions and Stars of David, and visitors would sometimes find Scratch planting records and tapes in the garden. As Bob Mack writes, “By the mid-70s, Perry’s Black Ark had become the cultural/spiritual center of hip Kingston and birthplace of reggae’s most conscious black pride anthems, all of which were either written or coaxed out of the artist by Perry (who at that point was beginning to infuse all his productions with the complex set of Christian, African, Arthurian, and Jamaican folk references that comprise his current cosmology.)”[16] Soon after Haile Selassie died in 1975, Perry and Marley helped reaffirm the faith for millions by cutting the ardent “Jah Lives.”

Even the name of Perry’s studio was archetypal, resonating with any number of prophetic crafts: the Ark of the Covenant, Noah’s craft, Garvey’s Black Star Line — all messianic revisions to those vessels that abducted Africans into slavery. But the Black Star that Perry followed lied in the depths of space. In an interview with David Toop, Scratch discussed Black Ark in such extraterrestrial terms:

It was like a space craft. You could hear space in the tracks. Something there was like a holy vibration and a godly sensation. Modern studios, they have a different set-up. They set up a business and a money-making concern. I set up like an ark….You have to be the Ark to save the animals and nature and music.[17]

Perry’s unique fusion of premodern myth and postmodern machines not only shapes his lyrics (in one of his weirdest songs, Perry warns “scavengers,” “vampires” and “sons of Lucifer” that “Jah Jah set a super trap / to capture you bionic rats”), but infuses his technological practice. Exploiting equipment that was archaic even for its day, Perry became a dub alchemist, weaving magnetic, tape, wires and circuit boards into the playful web of his magical thinking. Indeed, Perry spoke about his relationship to technology in explicitly animistic terms:

The studio must be like a living thing.. The machine must be live and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine by sending it through the controls and the knobs or into the jack panel. The jack panel is the brain itself, so you’ve got to patch up the brain and make the brain a living man, but the brain can take what you’re sending into it and live.[18]

Improvising his cuts on the fly, Perry would whirl like a dervish behind his SoundCraft mixing board, blow ganja smoke directly onto the recording reels, even drink the alcohol used to clean the tape heads when he ran out of Dragon Stout. This erratic behavior came to a head in the late 1970s, when Perry started glimpsing UFOs, kicked anyone with dreadlocks out of the Black Ark, and covered its walls with deranged scatological prophecies. In 1979, during what could generously be called a bout of severely eccentric behavior, Perry trashed and burned his studio, and according to some reports wound up briefly in a mental institution.

The question of Perry’s sanity opens up the tangled relationship between tricks, madness, art, and the prophetic imagination, but what is most important about Perry and his astounding musical legacy is how they highlight an often ignored strain of New World African culture: a techno-visionary tradition that looks as much toward science fiction futurism as toward magical African roots. One finds this fusion in the experimental cosmological jazz of Sun Ra, who also pioneered the use of synthesizers and African percussion; in Jimi Hendrix’s “electric church music,” which psychedelicized the guitar with feedback and studio effects; in the juicy cosmic technofunk of Parliament-Funkadelic mastermind George Clinton, which, as Cornel West writes, “both Africanizes and technologizes Afro-American popular music.”[19] Hip hop music also began with an totally unexpected redeployment of turntable and mixing technology (introduced to the South Bronx by the Jamaican DJ Kool Herc), creating what Tricia Rose calls “an experimental and collective space where contemporary issues and ancestral forces are worked through simultaneously.”[20] Though predominantly secular, hip hop nonetheless hosts an intense subgenre of rappers who belong to the Five Percent Nation, a street-wise offshoot of the Nation of Islam. In contrast with the worldly concerns of gangsta rappers, acts like Brand Nubian, the Poor Righteous Teachers, Paris, and Lakim Shabazz fuse hard-hitting political prophecies, righteous moralizing, and bizarre numerology into a forceful amalgam of Black Pride and imaginative Afrocentric “science.”

This loosely “gnostic” strain of Afrodiasporic science-fiction emerges from the improvised confrontation between modern technology and the prophetic imagination, a confrontation rooted in the alienated conditions of black life in the New World. According to Greg Tate, who sees science fiction as continuing a vein of philosophical inquiry and technological speculation that begins with Egyptian theories of the afterlife, “black people live the estrangement that science fiction writers imagine.”[21] As Perry’s own scathing protest music proves, the prophetic art that arises from this condition of perpetual exile does not simply “escape” from the pragmatic demands of politics. But neither does it deny the ark of the imagination that lies on the other side of the inner door, a tricky craft capable of navigating through the shadowed valleys of this world, guided by a black star whose very invisibility renders its virtual possibilities infinite.

Footnotes

Footnotes:

[1] John Corbett, Extended Play: Sounding Off from John Cage to Dr. Funkenstein, (Duke, Durham, 1994), 128.

[2] Grand Royal, issue 2, 1995, 69.

[3]Ibid, 62.

[4]Leonard Barrett, The Rastafarians, (Beacon, Boston, 1977), 108.

[5]Ibid, 111.

[6]Unpublished thesis.

[7]Barrett, 173.

[8]Ibid, 217.

[9]Ibid, 216.

[10] Ibid, 130.

[11]David Toop, Ocean of Sound, (Serpent’s Tail, London, 1995), 129.

[12]Dick Hebdidge, Cut’n’Mix, (Comedia, London, 1987), 82.

[13] Corbett, 23.

[14]Pelton, 268.

[15]Grand Royal, 64.

[16] Ibid, 62.

[17]Toop, 114

[18]Ibid, 113.

[19] Cornel West, “Out of Motown,” Semiotext(e), Oasis, vol IV no 3, 93.

[20]Tricia Rose, Black Noise, (Wesleyan, Hanover, 1994), 59.

[21]Mark Dery, “Black to the Future,” Flame Wars, ed. Mark Dery, (Duke, Durham, 1995), 208.