Adding “subjectivity” to robots

Cynthia Breazeal has no time for me, but she’s still going to show me her robot. As we pass through the halls of MIT’s Artificial Intelligence lab, now spearheaded by the robotics guru Rodney Brooks, Breazeal — a youngish Korean-American snowboarding fanatic — explains how urgently she needs to complete her Ph.D. thesis. This is her way of telling me that she does not have the half hour or so to boot up Kismet, the robot that’s consumed her research days for the last three years. Bummer.

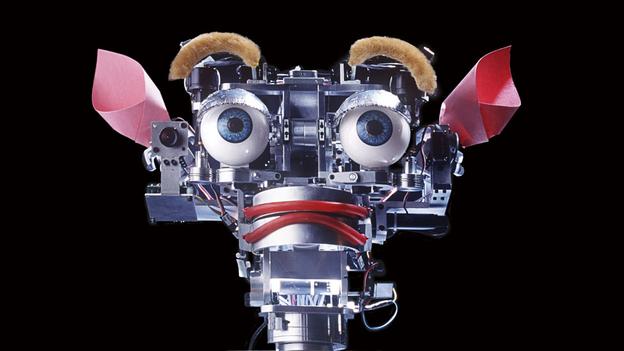

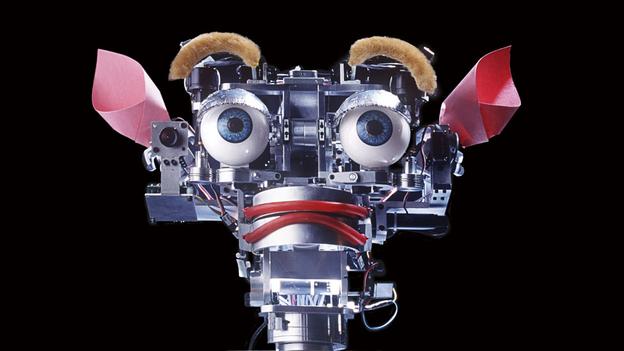

Then we round a corner and I glimpse her pride and joy, anchored to a mundane workbench. Even asleep, Kismet is fascinating. You might expect the latest anthropomorphic robot of one of the most prestigious engineering universities in the world to strike the eye with formidable force, like an android Iron Man, or a Barishnikov of articulated motion. But despite his exposed armature, Kismet seems sweet and approachable, like a robot raised by a kindly woodsman or a prototype prop from Teletubbies 2. With his big doe eyes, donkey-like ears, and absence of limbs, Kismet looks like a Furby who has clamored a few more rungs up the Lamarkian ladder of technological evolution, shedding his fur and becoming even more disturbingly cute.

The cuteness, at least, was intentional. After all, if robots are to eventually move out of the assembly plant and into ordinary people’s lives, they must develop social interfaces that can attract and sustain the attention of humans. One of the easiest ways to achieve this feat is to program machines to look and behave like humans or mammals. “Our goal with Kismet is to make the robot as readable and intuitive and natural as possible,” Breazeal says, explaining Kismet’s childlike appearance. But the goal Breazeal set for herself went far beyond Kismet’s armature and programming, and into the social relationship that includes both robot and human being. “We wanted to create an infant-caregiver-like interaction,” Breazeal explains. “People evolved to be socially intelligent, and we think robots can benefit from this kind of intelligence.”

Kismet’s goofy ears and Walter Keane eyes are already enough to trigger gooey feelings inside human beings, but the machine’s resemblance to a budding mammal is more than cosmetic. Besides keeping his sensors and servos up and running, Kismet’s fifteen computers — including a Linux box, Macs, various home-brewed boards, and nine four hundred megahertz computers for vision alone — run a variety of behavioral and emotional models based on early human development. These models give Kismet specific drives, similar to our own genetic drives for comfort, contact, and communication. At the same time, the robot’s appearance is also designed to trigger the human impulse to nurture young mammals. After all, there are good Darwinian reasons for finding big eyes cute, whether on puppies or Japanese manga babes.

By tricking humans into feeling like proud mamas and dadas, Breazeal hopes they will be drawn to nurture the robot, enabling the machine to actually learn from us the way we learn from our caregivers. Specifically, Breazeal hopes people will perform the same slow, repetitive and patient games that help young children to understand the world around them. “People treat infants as being more intelligent and consistent than they are,” Breazeal explains. “They model their own mind on the child. We want them to do the same thing with Kismet.”

***

The moment Rodney Brooks shows up in the lab, Breazeal takes the opportunity to cut out. Dressed in a snazzy blue suit, hair cut and trim, Brooks does not resemble the bug-eyed wildman who provided the title and much of the energy for Errol Morris’s documentary Fast, Cheap and Out of Control. Instead, Brooks looks like the department head he has become. “Now I spend all my day talking to journalists,” he says with a grin. “I barely even answer my e-mail anymore.”

Back in the late 1980s, Brooks helped revolutionize robotics with ideas that eventually wound up scuttling across Mars. Instead of the traditional AI approach to smart machines, which tried to program robots with centralized symbolic representations of the world around them, Brooks imagined machines that learned about their environment by exploring it according to simple, highly distributed rules of behavior. The inspiration for Brooks’s first robots were not chess-playing automata, but insects.

From the beginning, though, Brooks’s approach was far more than a design strategy. His vision implied a profound philosophical turn away from the Cartesian premises of classical AI, which imagines the human mind as a disembodied symbolic processor. Instead, Brooks believes that cognition emerges from the history of the organism’s interactions with the world around it, interactions which themselves are thoroughly distributed throughout the body. The results of these simple interactions are subsumed into higher global behaviors, which ultimately lead, at least in us, to consciousness. Brooks’s approach is, to use overly simplistic terms, “bottom up” rather than “top down.” To be conscious is to be engaged in a world.

In order to test their theories about the role of embodiment in robot cognition, Brooks and his team built Cog, a man-sized head and torso designed to learn about its environment through trial and error exploration. At first, the lab wasn’t thinking about modeling anything like human development; they just wanted to train Cog’s sensors and basic behaviors. “But eventually,” Brooks says, “we realized that the learning problems got easier if you did them in stages instead of having everything all on at once — much like a baby develops. If you do that, then each of the learning problems became much lower dimensional and much easier to manage.”

This realization planted the seeds for Kismet. But what really got the team jazzed about building a social robot was a curious behavior that Cog displayed one day when they were filming it interacting with Breazeal. In the clip, Breazeal moves a block, and then Cog, following her motion with its eyes, tries to grab the object. Breazeal moves the block again, and Cog repeats his action, this time dropping the object. “So what’s going on there?” Brooks asks about the scene as he plays it back on his Powerbook G3. “She’s doing something, the robot’s doing something, she’s doing something. To an external observer, it looks like they’re taking turns. But the robot has no turn-taking code in it.”

This emergent behavior got Brooks’s team considering the way that people, especially mothers, play with their kids. “Think about the way in which mothers lead their infants in behaviors,” Brooks explains. “The mother is doing stuff the kids can’t quite do by themselves, but the mother isn’t thinking ‘Oh, the kid can’t do it.’ Instead, they’re playing a game together. And out of that game the kid gets exposed to stuff from which they can learn.”

The idea of encouraging shared behavior dovetailed with another problem that concerned some of the AI lab’s corporate sponsors. “How can you show a robot how to do something?” Brooks asks, picking up a pen as an example. “Let’s say I’d like to be able to tell you to put one thousand pens together. Well, I don’t want to hack C++ code. I just want to talk to you. But I also know when you are not paying attention.” He waves the pen. “I show you this and then I glance up at you to see where your eyes are. So we’ve got this shared attention between us. You nod when it’s making sense and that makes me understand that I can explain more. So you control me and I control you. There is no master.”

This vision of shared attention and level interaction is leaps and bounds away from traditional robotic ideas, which often conceive of robots as slaves — capable of self-movement, yes, but not autonomous in any real sense. The master-slave dialectic is not just Hegelian runoff. In the world of telerobotics, where human operators control mechanisms at a distance, the two sides of the action are explicitly dubbed “master” and “slave.” But Brooks and Breazeal are imagining something quite different: a feedback loop in which humans and machines constantly modify one another. As such, their work has moved beyond the challenge of simply engineering better robots — they are also engineering a new kind of social relationship. “Kismet was designed to be a human-robot system, not just a robot,” explains Breazeal. “What we know about people is being put into the system. It’s designed for human nature.”

***

Kismet may or may not open up new avenues in robot research, but that’s not why you are reading about him here, in the first installment of The Posthuman Condition. I’m interested in Kismet because he can tell us something about that “human nature” that Breazeal is so interested in feeding into her system. Human nature is a mercurial thing. Composed of enormous redundancies, we are also protean, historical beings. So I think it is fair to suggest that human nature shifts in a world where an artifact like Kismet is even possible. The word kismet means fate, and that is how I choose to read the robot: as one more fractured augury of the cyborg subjectivity that we are booting up as we plunge towards an age of spiritual — or at least psychological — machines.

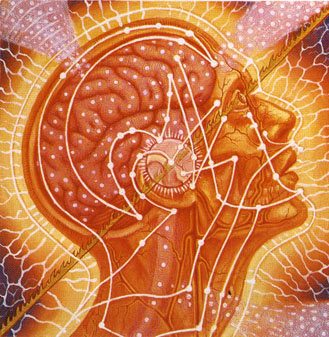

Of course, technology has always been a reflection of our images and understanding of ourselves, not to mention the larger social and political forces that inform subjectivity. This is particularly true when you are talking robots, which almost by definition imply some model or concept of human activity. In pop culture and industry, robots and toylike automatons have already donned the guise of slaves, workers, musicians, playmates, beasts, warriors, and — coming soon to a porno shop near you — sex partners. Kismet, in turn, reflects new concepts about early human development, concepts that have already started to alter our image of the human self. From the growing sexiness of neural science to the exploding market for infant intelligence toys, we are becoming obsessed with the malleability — the programmability — of the young nervous system, when the budding brain translates its physical and cognitive environment into wetware.

If robots like Kismet are mirrors of ourselves and our desires, then they must ultimately raise the same question that all mirrors do: Who is staring back? When we look into the sensors and cameras that serve as eyes in a robot like Kismet, what do we see? Machines, software agents, emergent avatars? But the question of how and when we will perceive robots as conscious agents is intimately tied to the question of how we come to view our own consciousness and agency. The Turing test is a parlor game, a rationalist trick: The real issue is not whether or not the machine can trick us, but how the presence of technological Others makes us revise our own self-image, our own experience of ourselves. “Who is staring back?” melts back down to the most ancient of queries, “Who am I?”

The impossibility of answering this question to anyone’s lasting satisfaction is one thread of that existential conundrum — tapestry? prison? trap? — we have come to call “the human condition.” We are no closer to answering that question today. At the same time, our technoscientific civilization is inching closer and closer to some mighty formidable answers to the more general question of what human beings are — or at least how they work. Scrape the creams off the latest findings in molecular biology, neuropharmacology, and cognitive science, not to mention the looser claims of evolutionary psychologists and social scientists, and you will find yourself loaded up with rich, pragmatic diagnoses of our “condition.”

How these technoscientific concepts will or should interface with the everyday selves we wake up in every morning is, needless to say, an open question. Indeed, the gap between blistering objective scientific accounts of human subjectivity and our own experience of that subjectivity — a necessary and nearly irreducible gap in my book — is a defining characteristic of what I am calling the posthuman condition. Of course, the scientific understanding of ourselves has always looped back and altered cultural and personal perceptions, even if images like the Cartesian watch and the Freudian steam engine proved cockeyed in the end. The current obsession with mechanistic neo-Darwinian accounts of agency, consciousness, and the self may prove equally lopsided, but these ideas are deeply influencing popular culture. Moreover, they are riding the coattails of actual products and practices, like gene splicing, human-computer couplings, and an expanding pharmacopia of psychoactive drugs.

As the implications of technoscience continue to sink in, we move ever closer to the pivot of subjectivity. We may wake up one day soon, already halfway across our own cyborg Rubicon, with the old humanist stories about freedom and will simply running on autopilot. The mid-twentieth-century mind was rocked by the knowledge that human beings could actually destroy the planet, but this realization was only a foreshock of our imminent ability to engineer the biosphere, to create transgenic species, to clone ourselves, to alter the human gene line, and even to edge up against the programmed senescence of cells. When the human condition itself is up for grabs, even in theory, then we are no longer exactly human.

Of course, after years of postmodernism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, and all those other poster children for our belated zeitgeist, “posthuman” might just further muddy the waters. The malleability of humanity — the unnatural shiftiness of human nature, which always slips beyond itself — was already a fundamental axiom of Renaissance humanism, when the Florentine Pico della Mirandola put these words in the Supreme Maker’s mouth: “We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the form you may prefer.”

In the minds of many of today’s self-proclaimed “posthumans,” Pico’s rallying cry has simply gone futurist. For these folks, also known as transhumans and extropians, science and technology are opening up a glorious techno-Nietzschean millennium of longevity, neural self-programming, cyborg symbiosis, nanotechnology, and rapacious libertarian economies. This “Up with cyborgs!” boosterism does serve the vital role of reminding us how our fundamental beliefs about what is and is not possible are changing on an almost molecular scale. But in their almost adolescent hatred of limitations, extropians ignore the screwy cultural and psychological consequences of our changing human image, let alone the dark side of all these Faustian pacts. For me, the posthuman condition is a far more critical, ambiguous zone, one in which technoscience deepens rather than resolves the contradictions that characterize the fragile ground we walk upon.

One boundary of this zone is our deepening symbiosis with machines. In the twentieth century, one dominant myth imagined technology as a massive dehumanizing force — just think of Charlie Chaplin as a cog in the machine of Modern Times. But Kismet points to a very different world, neither a dystopian Metropolis or a utopian transhuman paradise. With Kismet, humanness is neither eradicated nor finally fulfilled, but swallowed up inside a technological design. In other words, humanness becomes a feature.

The paradox is that in order to inject human qualities into the “robot-human system” that the AI lab set out to construct, they had to understand certain things about humans in as quantifiable and objective terms as possible. They had to gain some knowledge of how we track each other with our eyes, how we respond to infants, how infants respond to external cues. In other words, to make Kismet behave naturally, the Lab had to understand humans as machines — highly complex and adaptive machines to be sure, but machines nonetheless. Even if we recognize that human development is an astoundingly complex “holistic” process driven by a symphony of causes, we still can begin to nudge that complexity out of circuitry. This is, after all, what Rodney Brooks has always tried to do with his robots, whose behavior is a global effect of many smaller and simpler processes running in parallel.

In Breazeal’s “human-robot system,” human nature does not disappear but becomes abstracted from the embodied social interaction of hairy primates, translated into code, and then fed back into an expanding cybernetic system that includes both human and machine agents. This is an allegory for the future, a snapshot of the posthuman condition. It remains to be seen whether we will optimistically expand the range of human qualities to include machines, bringing them at least partway into the circle of agency, or whether friendly-faced technology will increasingly seem to parrot, undermine, and even usurp our simian sociability. One thing seems sure. No one holds the copyright on human nature, and no one controls the drift of human characteristics into technological avatars. We may sometimes feel like slaves to our technology, but, as Rodney Brooks put it, there is no master.