The Secret Museum Of Mankind

One afternoon, in the same anthropology section of San Francisco’s Austen Books where I scored cheap editions of Conversations with Ogotemmeli, The Gift, and a rare copy of Herskovitz’ Life in a Haitian Valley, I stumbled across a mighty bizarre volume known as The Secret Museum of Mankind. Lacking page numbers, pub date, or any editorial information beyond the name of an obscure press (Manhattan House), this apparently early-1930s volume consists of a couple thousand captioned “photographs” of traditional folks from the four corners of the globe. I say “photographs” because many of these portraits and scenes have been retouched as blatantly as the average Weekly World News cover shot, and a few are basically cartoons.

Which is appropriate, because The Secret Museum is no-bones exotica, reflecting early pop anthropological obsessions with racial typology, hygiene, and nipples of color. Nevertheless, these simultaneously gaudy and fading images are powerful, arresting, and impressively strange: a Congo woman’s globular scarifications, a Burmese tyke smoking a cheroot, a group of Arunta tribesmen doffing Dr. Seuss wizard-caps. There are South Sea cannibals, Kirghiz nomads, and the “Fuzzi Wuzzi Woman of the West,” whose gravity-defying hairstyle belongs on a Pedro Bell Funkadelic album cover. You can’t even accuse The Secret Museum of being Eurocentric — one section includes Dutch milkmaids, cross-dressing Irish straw boys, and Canary Island “troglodytes.”

The Secret Museum‘s captions are a hilarious blend of clueless condescension, cheery racialism, and loopy fashion critique, and require no post-colonial fake books to deconstruct. (“Her disk-sewn neckband and rope of beads are the chief pride of this Ainu maiden whose grotesque tattooed mustache cannot quite destroy her ingenious youthful charm,” reads a typical entry.) Since these captions are basically data-free, the only frame provided for the photos comes from our own raw fascination. Stripped of anthropological machinery, these faces simply amaze; some recall friends and lovers, while others stare out like bizarre carven idols from some pulp otherworld. Of course, the hack artists who helped flesh out The Secret Museum don’t let us forget that these “photographs” are halfway projections of the rootless American eye. But our pleasure persists nonetheless, or mine anyway, at once a guilty orientalism and a dreamlike embrace of the universal human carnival.

Fans of traditional non-Western music know this paradoxical pleasure well. I say fans and not scholars, for there’s always fantasy in fandom, while ethnomusicology is too often a dry sport of pinning butterflies. The information crammed into today’s non-pop world music CDs is our fetish, a promise that all ghosts of exotica will be exorcised, all nomadic imaginings fixed in a briny, anthropological pickle. Preservation is a valuable and necessary goal, but too often suffocates the more errant power of other people’s music to send us tripping out of ourselves.

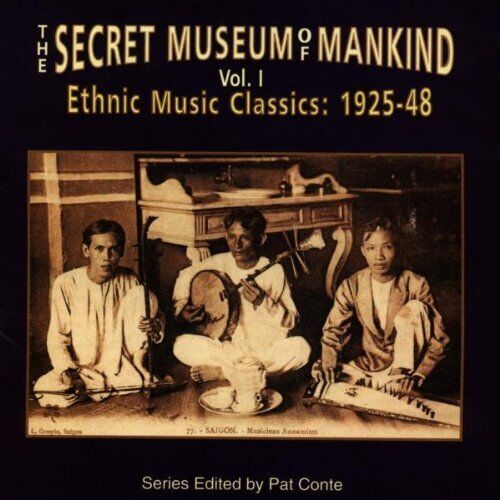

When the record collector Pat Conte named his recently-debuted compilation series of rare and remastered “ethnic” 78s after The Secret Museum of Mankind (it’s also the name of Conte’s enormous personal collection; his WBAI radio show is called The Secret Museum of the Air), he wanted to highlight the spectral and romantic spell induced by these crackly tunes rather than their considerable documentary significance. After all, the original 78s were created not by intrepid field scholars like Alan Lomax but by early record companies eager to stimulate enough pleasure to induce people the world over to buy record players. As with the blues and hillbilly sides cut in the States, most of the recordings collected on The Secret Museum were made in the field, with the subsequent discs sold back to local communities or to immigrant pockets in the West. And while it’s impossible to know how the performers felt about being captured on wax, they certainly weren’t building a career for a mass market or preserving their authentic folkways. Being recruited by the record companies was probably more like getting your best cow photographed the resulting souvenir became a source of pride, pleasure, and community honor.

Recorded in places as far-flung as Kazakhstan, Rapu Nui, and Cape Breton, the performances collected on the first two volumes of The Secret Museum are almost entirely excellent, making this one of the more consistently rewarding compilations in years. The cuts range from 130-bpm Macedonian fiddle jaunts to Puerto Rican Christmas tunes, from Abyssinian religious chants to ominous Japanese court music, from down-and-dirty klezmer to the psychedelic minimalism of a Javanese “new song.” The instruments include Ukrainian sleigh-bells, Sardinian triple pipes, Vietnamese moon lutes, and Ethiopian one-string violins. Though some of these tunes were little more than entertaining ephemera for the folks who made them, Conte’s choices sound like masterworks today, a profound and playful artistry lurking beneath their alien vernaculars.

Falling in love with these tunes can be dangerous one risks both the politically dubious spell of exotica and the postmodern heresy of recognizing universal emotions in these distant sonic subjects. But when I hear Smyrna’s Rita Abatzi sing a mournful cafe dirge over spare instrumentation worthy of Joy Division, or the Swedish master Eric Sahlstrom play an airy, bittersweet strain on his medieval-era keyed fiddle, or Trinidad’s Lord Invader rail with vindictive mirth against “hooliganism” over “Old Time Cat-O’-Nine”‘s exuberant clarinet, I hear the basic beats of the human heart.

That’s not to deny the bizarre shit herein. Sardinia’s Effisio Melis pulls a Rashaan Roland Kirk on his triple pipe: while a drone cycles miraculously without a breath-stop, his hyperactive pastoral dance builds to a chaotic cluster of insanely trilling birds. Master Manahar Barve’s “Gungru Tarang” is a simple Indian folk tune played on harmonium and violin, but the melody is echoed by suspended clusters of differently-tuned bells that sound like astral cloudbursts or the resonating sighs of sylphs. And the strangest cut doesn’t come from the jungles of Borneo or the steppes of inner Asia, but from France. On “Jabadao de Quimper,” the Bretagne duo Les Freres Sciallour plays a squealing folk-metal leprechaun jam on their eerie little druid pipes.

Walter Benjamin claimed that mechanical reproduction leeched the aura from art, an aura that in indigenous music is nothing less than the lived spirit of passing time. Before recording (or musical notation), even the oldest musical forms were contemporary or not at all. The magical glue that unifies The Secret Museum‘s otherwise disparate recordings is the afterimage of that aural aura, of the moment when technological reproduction and the commodity form had just begun to capture and irreparably reconfigure the evanescent flux of musical memory. Only the most smug postmoderns would deny the autumnal tone this poaching lends these cuts, a melancholy deepened by the knowledge that nearly all of these musicians must be dead, and most of their lifeworlds severely eclipsed.

But false nostalgia is a sucker’s game, and it’s mushy-minded to interpret the greasy fingerprints of colonialism that gum up these cuts as signs of tyranny and loss. After all, in the hands on non-Western musicians, imperialist flotsam like violins, clarinets, Christian choruses, and pump organs offer opportunities for syncretic mutation, from the unmistakably African polyphony of Nigeria’s Eleja Choir to the flattened bridge used by a Rajahstani violinist to allow for drones in “Jat Song.” Even though the harmonium’s lack of microtones does violence to Indian modes (and pissed off purists in its day), this Victorian contraption had become, by the time Professor Narayanrao Vyas recorded his ecstatic hymn to Krishna’s mom, one of India’s most definitive popular instruments.

Folk music has never been pure; its creative mutations, cannibalizations, and cross-cultural thefts make up its living continuity as much as the conservative retention of rhythms and tunes. Certainly “Kapirigna,” a manic Afro-Portuguese/Sinhalese street romp recorded in Ceylon, is as “authentic” as it is scrambled. But what about “Naidasay Toy Pusac,” a Spanish-tango-inflected Phillipino tune recorded in L.A. by a Visayan Islands duo using the newly-invented dobro? Beats me.

I just keep coming back to that spooky technological aura, the snap crackle pop of weathered 78s that defines early recordings the way washed-out videotape defines ’70s sitcoms. Today, computerized signal-processing is getting pretty good at remastering these old platters. But one man’s message is another man’s noise, and though the rarest of Conte’s cuts were initially “more noise than music,” he wisely chose to leave his remastered tunes somewhat scuzzy. Besides preserving more of the original recording, this remaining surface noise spills the dustbin of history into the digital clean room of today’s musical universe. When I hear the scratchy samples of Tricky, Portishead, or the Mo’ Wax crew, I hear entropy, death, and vinyl ancestor-worship. But when I listen to the nightstorm of static that bathes G. Kurmangaliev’s Kazakhstani lute or Sa Zen Ga Zhiu Luh’s serpentine Tibetan melody, I hear nothing less than the immense but muted roar of all strange, lost, and forgotten music, the long ago strains of humanity’s joyful noise.