The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher

When I was researching The Visionary State, my book about Californias eccentric religiosity, I had the pleasure of meeting many marvelous characters from out of the depths of time. My hands-down favorite was a a longhaired prophet of God with the extraordinarily groovy name of Lonnie Frisbee, who more or less single-handedly turned the Jesus People movement into a mass phenomenon, as well as inspiring two of the most dynamic Protestant revival movements to appear over the last thirty years (Calvary Chapel and the Vineyard). During my research, I got in contact with David Di Sabatino, a freelance Christian historian and author of a massive out-of-print bibliographical resource on the Jesus People Movement. He told me he was making a documentary, which came out last year and played on some PBS stations and at a few biker churches in Orange County. Now it’s on DVD.

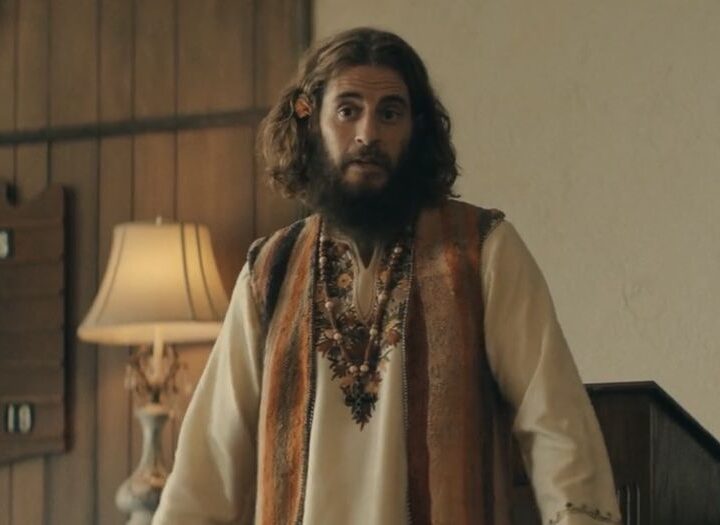

Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher is a straightforward if exemplary documentary — concise, intelligently edited, and utterly fascinating. The prophetic figure behind the Jesus Freak phenomenon is about as perfect a subject for a biopic as could be imagined. In the mid 1960s, Frisbee was a LSD-fueled pothead naïf from a crappy home in Costa Mesa, Orange County. He spent a lot of time getting into the mystic in the canyons near Palm Springs, where legendary proto-hippies like Gypsy Boots, eden ahbez, and other Nature Boys had lived raw and wild as early as the 1940s. Shortly before the Summer of Love, Frisbee made his way to Tahquitz Canyon, bringing along a Bible, paints, and some LSD to drop with other skinny-dipping freaks. Tripping hard, Frisbee asked God to reveal himself, and He did. Frisbee was granted a vision of the Pacific Ocean drying up and filling with hordes of people, who raised their hands to heaven and cried out to be saved. Not long afterwards, Frisbee made his way up to the Haight, where he encountered street Christians who ran a hippie café called the Living Room. Here Frisbee’s conversion became complete, but he kept the long hair and scruffy threads and wide-eyed visionary innocence — an authentic, infectious passion and spiritual intensity that Christians would call the Holy Spirit, but which in this context had as much to do with the mystic counterculture as it did with all but the most Pentecostal wings of American Christianity.

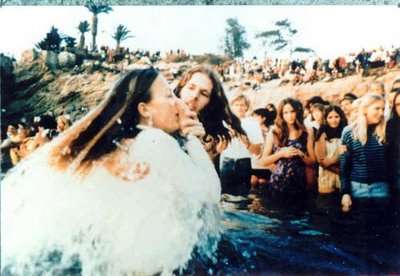

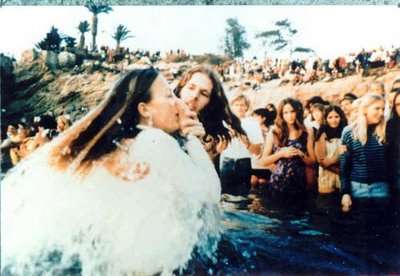

A year later Frisbee was back in Costa Mesa, where he met Chuck Smith, who headed a small nondenominational church called Calvary Chapel. Smith wanted to minister to the hippies and potheads of the coastal town, and invited Frisbee, who was a spitting Anglo image of the savior, to preach. Frisbee proved attractive and charismatic, and his extraordinary success with young people helped turn the Jesus movement from a California eccentricity into a mass phenomenon. Christ became a long-haired revolutionary of love, and his followers used countercultural media like underground newspapers and folk-rock to turn on others to the convulsive power of the Holy Spirit.

In 1971, Frisbee parted ways with Smith, who became wary of the magnetic evangelists Pentecostal (and implicitly hippie) emphasis on intense conversion experiences rather than the more prosaic task of working line-by-line with Scripture. Freed from Frisbee, Calvary Chapel went on to become an immensely successful international movement that was morally conservative but lively and antiestablishment in tone. Frisbee himself plunged even deeper into signs and wonders, and on Mothers Day, 1980, while preaching at a Calvary Chapel church in Yorba Linda, Frisbee exclaimed Come Holy Spirit, and the hall erupted in tongues and healings and prophecy. The power unleashed by this event eventually caused a split between John Wimber, the churchs pastor, and Calvary. Wimber went on to spearhead Vineyard Christian Fellowship, which would in turn become one of the most influential and controversial charismatic movements of the last twenty-five years. But once again, after lighting the fire, Frisbee was soon dropped like a hot potato. As this boomer great awakening represented by Calvary Chapel and Vineyard settles into middle age, Lonnie Frisbees catalytic role has been, until Di Sabatino’s work, quietly covered up.

One of the understated marvels of Di Sabatinos documentary is how long it waits before dropping the biggest bomb about Frisbee, and how gently and unhysterically the drop actually occurs. Throughout his nomadic ministry, Frisbee struggled mightily with the fleshand man-flesh to boot. As Chuck Smiths son admits in one of the doc’s many fascinating interviews, this is not the rarest thing in Christian pastor circles, although it is condemned with far more intensity than comparible “sins.” Frisbee was in many ways condemned by it, almost as if he was forced to carry the cross of the hedonistic, polymorphous mystic spirit that shaped him as a young mana freak martyr, as it were.

In 1993, the onetime Jesus freak coverboy died of AIDS, raising issues that most people in the evangelical community would rather ignore. Di Sabatino handles this issue with extraordinary delicacy. Doctrinally, most of the people he talks to tend to hold that practicing homosexuality is, in itself, a sin. Now, like many of you reading this, I suspect, I never found anything particularly threatening or disturbing about gay folks, even when I was a kid. Because of this I react to strident fundy anti-homosexuality with as much puzzlement as anger. Nonetheless, I was impressed with how these SoCal Christians, with their David Crosby chops and loud Hawaiian shirts, dealt with the hypocrisies of their fellow Christians and their own understanding of the relationship between sin, however it is conceived, and practicing Christianity.

Indeed, one of the great things about Frisbee is the insight it gives the viewer into contemporary Christians — or at least contemporary Christians who have been influenced by the Jesus movement. For people who don’t spend too much time around Christians or honest Christian media, the whole scene can seem pretty alienating — a scary crew of screaming ideologues, bellicose Bush supporters, paranoid critics of secular culture, and zombies of faith. The folks revealed in Di Sabatinos doc are a entirely different breed: funny, conflicted, compassionate, and sensible, while still acknowledging the mad anointing power of the Holy Spirit — a power that, in Frisbees hands, achieved a visionary but gentle ferocity that drove home for me the difference between living religion and blinkered beliefs. As the scribbler of the Pentateuch asked: would that all the Lords people were prophets.

After spending years researching religion and California, I came to the conclusion that something unique happened in my home state, and continues to shape American religion and American consciousness. Most of the important stories I told were outside of Christianity, or at least on its far fringes. Frisbee, for me, is proof that the intense countercultural spirituality of the Golden State in the second half of the twentieth century had a Christian face as wellLonnie Frisbees, to be exact. But also thousands of others, as can be gleaned from some of the amazing shots and clips that Di Sabatino has included of early 70s Orange County beach baptisms led by the grinning golden boy. (Di Sabatino is also a Jesus People music fiend, and the films soundtrack, which features rare psych-folk gems from Agape, All Saved Freak Band, and Gentle Fatih, will, according to the website, soon be released.) As someone who spent six months of my spiritually haunted teenage years attending born-again Bible study with a long-haired and young surfer preacher, I was unusually satisfied by Di Sabatino’s quiet revelation of one of the great stories in American religion. Frisbee is a key lost gospel of California, and a strong and vital reminder that the American Jesus wears many faces, including hirsute and beaming ones.