Here is the story I wanted to tell: There is a grinding contradiction at the core of the current MAGA coalition, a fundamental conflict in worldview and values that is so extreme that the temporary expediency that currently cloaks this split is doomed to erode into mutual distrust, rivalry, and even open revolt. Pointing out and articulating this contradiction, I wanted to say, might even help hasten its exposure, as the word gets out that the orange emperor has no clothes — or rather, that he is wearing clothes that dangerously clash.

The heart of this unfortunately delusional story — and it is a delusion, as I will explain in a moment — is the seemingly obvious incongruity between the accelerationist orientation of libertarian Silicon Valley technologists and the reactionary hunkering down of conservative Christian nationalists — two groups that provide some of the most dynamic cultural and political fuel to the Trump administration’s conflagration of the American state.

While each “side” actually represents a complex spectrum of positions, I follow old Max Weber: it’s sometimes helpful to essentialize or even caricature core value positions in order to understand the motivations of large groups of social actors. So here we go.

Nietzsche famously and correctly argued that the Achilles heel of modernity is nihilism, the raging abyss of meaninglessness over which the tightrope to the future is stretched. Conservative Christians living in modernity have traditionally dodged this acid bath by holding to an absolute rock of certainty, and to a fundamental(ist) establishment of moral and natural law. Leaving aside their myriad theological differences — establishing the One Way has always been the toughest of traveling salesman problems — the vast majority of conservative Christians in America, whether evangelists or fundamentalists or Calvinists or pre-Vatican II Catholics or newly minted Ortho Bros, share a profound distrust and even horror of the corrosive, tradition-eroding powers of modernity — that era when, as Marx famously said, “all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”

This deep ambivalence about modernity also shapes the basic sense of the self. In the face of the technocultural explosion of novelty and choice, and the secular and liberal pluralism it has largely installed, conservative Christians have tended to root themselves in the embrace (and sometimes rigid imposition) of boundaries. These “lines in the sand” define the edges of one’s actions, tolerances, and ethical norms, and install crisp and often “traditional” limits on situations perceived as chaotic, unruly, or perverse. (Hence the fetishes for borders, defense, and gender normativity.) And nothing shores up such lines in the sand so much as the forceful energy of unwavering belief, an attitude captured in the bumper sticker that in a way says it all: “God said it, I believe it, that settles it.”

This stands in opposition to the techno-libertarian ethos, which actively enjoys and intensifies the progressive disruptions unleashed by tech and markets, whose novel possibilities and radical unboundedness are seen as forms of freedom and self-making. As a style of selfing, this mode has more recently cashed out, in the Valley anyway, as a kind of nerdy postmodernism: identity is a LARP, ethics a square on a D&D alignment chart, and the closest thing to a church is Burning Man, where lines in the sand warp and shimmer as the LSD reveals a multiverse of pleasures and mutations.

When the sharper techno-libertarians acknowledge the problem of nihilism, they respond with Nietzsche’s jailbreak: the transvaluation of values. Humanity itself will change. Natural law be damned (except maybe the links between DNA and intelligence). Deploying reason and technique to hack the given, we can get out ahead of the limitations imposed by nature and social mores, not to mention our own baked-in cognitive biases. Pound smart drugs, practice jhanas, revise your priors, prep your skull for a Neuralink patch, and you too might dance across that tightrope into the cyborg arms of the Übermensch.

With its freethinking origins, libertarianism has largely steered atheist, if not outright Promethean. That may help explain why libertarianism has so long been strong among hard-headed technologists and engineers. I grew up in SoCal in the 70s and 80s, and the libertarians in the voting guides inevitably worked in technical fields. In more recent years, this spirit has manifested as technological solutionism, or the cult of genius engineers, or the alignment-be-damned school of AI accelerationism. Such bootstraps confidence has no need for ancient commandments or scriptural prophecies, and often sees them as damage to route around. As such, techno-libertarianism is only a hair’s breadth away from the Luciferian rebel yell that has long unnerved the God-fearing. Anton LaVey, head of the Church of Satan, was a libertarian who described his breed of Satanism as “Ayn Rand’s philosophy with ceremony and ritual added.”

That’s why I saw a massive MAGA collision on the horizon, a Royal Rumble of the Transhuman and the Trad. But I was wrong. In sync (as is often the case) with Jamie Wheal, who recently admitted to making the same predictive error, I now realize that, rather than a collision, we are instead witnessing a prophetic convergence. What lies before us is the emergence of Christian transhumanism, an explicitly eschatological accelerationism with righteous high-tech weaponry strapped to its side and the galactic New Jerusalem in its cyborg sights.

Of course, we are also talking Bay Area technoculture here, so it’s impossible to separate memes, hype, trendy journalism, and fundamental shifts in values and vision. But this part is true: in past decades, Bay Area tech culture was mocking or actively hostile to Christianity, and it is no longer. We may or may not be witnessing a genuine “tech revival”, but something religious is slouching toward Silicon Valley to be born.

For one thing, there has been an uptick in missionary efforts to virally direct the word of God towards coders, engineers, and entrepreneurs. San Francisco’s Epic Church has recently proved very successful in bringing a self-help-tinged gospel to tech folks. According to Jules Evans, who visited Epic one recent Sunday and described the church as a pleasant mainstream charismatic affair, the pastor Ben Pilgreen:

occasionally spoke about ‘secular business’ and ‘secular culture’ as something that surrounds them in San Francisco but they will somehow resist and transform. This is classic charismatic speak— they can sometimes think of themselves as a sort of underground rebellion surrounded by ‘secular culture’ yet resistant to it, a true counter-culture. However, at the same time these sorts of churches are deeply influenced by secular business culture…The service occasionally reminded me of a tech product launch.

The New York Times and Vanity Fair both recently published pieces about a San Francisco gathering called Code & Cosmos, hosted last October by Garry Tan, the president and CEO of Silicon Valley’s mighty start-up incubator Y Combinator. Both pieces directed ink towards Trae Stephens, Christian co-founder of the defense tech company Anduril with Palmer Eldritch (uh, Luckey). This is a crucial reminder that, as Jamie Wheal explains in the post linked above, the Valley’s shift towards conservative Christianity is intimately bound up with the new patriotism that fuels its significant turn towards high-tech defense development, both here and in SoCal’s Gundo. Trae’s wife Michelle also helped build the nonprofit ACTS 17, which sponsored the Code & Cosmos event. ACTS stands for Acknowledging Christ in Technology and Society, while the 17th chapter of the book of Acts — PKD’s favorite book of the New Testament — follows Saint Paul as he spreads the Word through various smarty-pants cities like Thessalonica, Berea, and Athens. Get it?

The Christian scientist Francis Collins, who led the Human Genome Project, spoke at the ACTS 17 event last October. But the gathering the previous May featured a much more influential and symptomatic figure in this 4k holy roller redux: Peter Thiel. Rightwing billionaire, big-dollar J.D. Vance supporter, Christian, Tolkien fan, and the VC Dark Lord behind PayPal, Palantir, and the Founders Fund (which backed Anduril), Thiel also serves as what Evans calls the “Cardinal Richelieu” of the emerging sensibility: the sometimes garbled and scattershot power broker of Christian accelerationism. “We don’t want to be anchored too much on nature,” he told the ACTS 17 crowd, speaking about transhumanism. “If there’s a Christian critique of these sort of utopian scientific movements, it should always be in the direction that they don’t go far enough. Transhumanism, radical life extension. It’s not that you shouldn’t live forever, but that it’s only transforming people’s bodies and not their souls and not the whole person or something like this.” [emphasis added]

In the Valley, Thiel has long been known for propagating the gospel of René Girard, a deeply Catholic theorist of religion and literature who taught for years at Stanford. I don’t want to get too tangled in Girard’s theory of mimetic rivalry, which is at once fascinating, perceptive, and kinda banal, but it helps illuminate some of Thiel’s otherwise obscure arguments about God and tech. In 2020, for example, Thiel claimed that, “When you don’t have a transcendent religious belief, you end up just looking around at other people. And that is the problem with our atheist liberal world. It is just the madness of crowds.”

This is Girard’s theory in a nutshell: Left to our own devices, humans want what they want by looking at what others want. This looking around inevitably leads to envy and rivalry and sociopathic tensions. (The theory also makes investments in envy machines like Facebook — which Thiel got a very early piece of — an extremely canny bet.) To maintain cohesion, Girard argued, societies have traditionally beat up a scapegoat — an unfortunate outsider who can be laden with all this pent-up social conflict and then destroyed or banished to the relief of all (except the scapegoat). Christ, in Girard’s thought, is the ultimate scapegoat. But because he is also the all-powerful and all-forgiving God, he upends the whole demoralizing system of social media(tion), opening up a transcendental dimension that springs the trap of envy that lies behind the madness of crowds. We escape by looking up.

As John Ganz points out, Girard’s critique of “invidious competition” also provides a theological basis for one of Thiel’s standout features as an economic overlord: his profound fondness for monopoly capitalism. Rather than waste time and indulge in meaningless competitive struggles, monopolies can, in Ganz’s words, “miraculously defeat the logic of the market and commoditization and can focus instead solely on ‘innovation.’” Innovation in Thiel’s view is not a response to market competition or even human desire, but instead expresses a radical force of novelty that drives history beyond nature and beyond human murk, and towards the kingdom of God. But for all of today’s remarkable digital tools, Thiel thinks we are actually slacking in that department. Real innovation is not a new smartphone app — which in some ways just feeds the envious world of mimetic desire — but the production of real machines, medical breakthroughs, new materials, and — to judge from Thiel’s investment strategies — overwhelming surveillance and defense capabilities.

Tara Isabella Burton, one of our best religious culture commentators, characterizes Thiel’s stance as “a distinct fusion of techno-utopianism that characterizes its successes as Christian miracles.” I am not sure if miracles is quite the right word — “direct expression of God’s providential role in history” is probably closer to the mark — but you get the drift. Here the heavenly hopes that sustain personal faith are remade into a civilizational gospel of technological optimism. In a 2015 piece called “Against Edenism,” Thiel wrote that “Judeo-Western optimism differs from the atheist optimism of the Enlightenment in the extreme degree to which it believes that the forces of chaos and nature can and will be mastered.” This language reminds us how mythology fuels this view. We are back at the beginning of things, facing a watery void, identifying with the divine engineer or the dominating patriarchal hero.

In what way is this conservative? As Sam Adler Bell explained a few years ago in a discussion of Thiel:

What this vision is not, is a conservatism of limits. Rather, it is Promethean, progressive, in the most basic sense: It deplores any constraint on its power to govern, shape the future, despoil the planet, innovate, and expand the American economy. All limits — pluralism, democracy, ecology, human frailty — must be overcome in pursuit of winning the world game, reasserting American dominance and dispelling our decadent malaise. (At one time, Mr. Thiel [was also] interested in overcoming the ultimate limit: death itself.)

Like the early Futurists of fascist Italy, Thiel wants the power of technology unburdened from restraint, and in a way that might even triumph over death and physical decay. His stance reminds me of a fascinating feature of Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea’s 1975 pulp conspiracy romp Illuminatus!, whose prophetic illumination of our time I discuss in my book High Weirdness. In the novel, the renegade anarchists of the Discordian Society fight an ontological guerilla war against the Illuminati, who manipulate and dominate society behind a conspiratorial veil. But the Illuminati are not reactionaries, or Traditionalists, or Straussian neocons. Like the Discordians, they are novelty junkies, “homo neophilus.” They are disrupters who shun traditionalism, embrace ecstatic techniques, and want to intensify the deterritorializing forces associated with capitalism, technology, and liberal modernity. In the great conservative historian Eric Voegelin’s timeless phrase (later voiced by William F. Buckley, Jr., and then by Shea and Wilson), they want to immanentize the eschaton.

Voegelin and Buckley wanted nothing to do with immanentizing the eschaton, which they associated with Marxism and heresy. But that’s what Thiel is talking about when he describes how the Enlightenment can overcome its secular Achilles heel by fusing with Christian eschatology. “Science and technology are natural allies to this Judeo-Western optimism, especially if we remain open to an eschatological frame in which God works through us in building the kingdom of heaven today, here on Earth — in which the kingdom of heaven is both a future reality and something partially achievable in the present.” Immanentize it, baby!

But there’s a problem: Christian eschatology comes with a big paranoid price, because Evil is always sniffing around the prophetic archetypes. Consider the Birchers who thought the United Nations was a Satanic usurpation, or the evangelicals who identified UPC barcodes as the “mark of the Beast” (Rev. 13:16-17). You might think that the cagey Thiel might keep his public Christianity restricted to techno-optimism, the nobility of the defense industry, or the depravity of the modern university. But lately, Thiel has been talking a lot about the Antichrist, and the one-world government that prophecy tells us gets installed at the onset of the end-times.

In recent interviews, Thiel insists on something amazing: that the one-world Antichrist system is currently as great an existential risk as runaway AI or nuclear war or climate disaster. He is not thinking about China here folks, but about the visions emerging from the famously crude Greek of the Book of Revelation. The fear is that, in the name of “peace and safety” (1 Thess. 5:3), the charismatic and holy-seeming Antichrist takes over our benighted planet, waves the rainbow flag of the Big Blue Marble, and starts regulating technologies and making everyone ride bicycles and genuflect before Greta Thunberg. In the bleakest of ironies, Thiel even worries about the “gigantic surveillance state” required for such global governance if it is to have any teeth.

Thiel’s fears are legitimate — it is hard to imagine an order of global governance that could, say, actively arrest the human causes of climate disaster without leaning into some seriously dystopian controls ripe for abuse. Absolute power probably does corrupt absolutely. Indeed, in my darkest hours, I fear that the only way to put the brakes on before we hurtle over the cliff is to install an unacceptably oppressive and cruel regime of power and control. In that sense, I agree that “we are all accelerationists now.” But at a time when the Left and the Greens are in tatters across the globe, the idea that the Antichrist system is as likely or even as worrisome as nukes or apeshit AI is bonkers.

But there’s an important insight lurking in this bonkers, and it relates to the fact that we are hearing about this “gigantic surveillance state” from a cofounder of Palantir — a major provider of surveillance data management services to governments, corporations, and — most controversially — the good folks at ICE. (And because myth is part of our story, we need to point out that creepy fact that the company is named after a magical elven artifact in The Lord of the Rings that is abused by the bad guys.) Thiel’s worries give us a glimpse of the way that religious (or literary) narratives function as ideologies: by allowing you to confront and acknowledge the negative charge of your own actions and investments while simultaneously displacing them or running them through the funhouse mirror of myth. In this sense, the new dispensation of accelerationist optimism is actually shot through with pessimism, resentment, and cruelty — shadowy projections it must also conceal from itself. Techno-eschatology allows the right hand — the correct, righteous, rightwing hand — to not know what the left hand, the sinister hand, is doing.

Upcoming Events

• The Three Stigmata of Elon Eldritch. Last year I did a five-part lecture series at the Alembic where we read through Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. The talks included drug politics, Gnosticism, and the prophetic analyses of our DOGE overlord (when Eldritch checks into the hospital in chapter two, he registers under the assumed name Eldon). Now my good pals over at Weird Studies have repackaged the talks into a course with me as part of their Weirdosphere world of content. Class participants will have the opportunity for a new live Q&A with me at the end of April. Class package available at the Weirdosphere.

• Embodied Writing and Spiritual Practice: If you are itching to spend five days on the dizzying edge of Big Sur, exploring the dynamic links between writing and the spiritual life, the opportunity is upon you. Between April 28 and May 2, I will once again be joining Sravana Borkataky-Varma for an Esalen workshop that combines writing practices, discussion, poetry, meditations, and chanting. In addition to being a good friend and colleague, Sravana is an initiate in and scholar of South Asian Tantra, and has a very dynamic and accessible teaching style. I handle more of the writing stuff. Come on down!

Appearances

• How to Navigate the Weirdness: I just gave two talks at the Berkeley Alembic on how to stay grounded and sane inside our current maelstrom of strangeness and dread, and they are now up for free on the Alembic YouTube channel (Part 1, Part 2). In the first talk, I tried to put the weirdness of our moment in a historical context — what Eric Weinstein calls the “70-year nap” — that focused on the beginnings of the postwar world and the 70s era I covered in High Weirdness. The second talk was more focused on survival tactics for the maelstrom while taking a Maybe Logic pit stop at the UAP rally. With my pal Christian Greer on whiteboard.

• The Affirmation of the Imagination: Speaking of Weird Studies, JF Martel and Phil Ford just posted a conversation I had with the boys about John Crowley’s book Little, Big. I wrote about this wonderful book in an earlier Burning Shore, and here we use it as a springboard to talk about enchantment, the esoteric imagination, urban fantasy, anomalous experience, faeries, and the transporting power of prose.

More Books

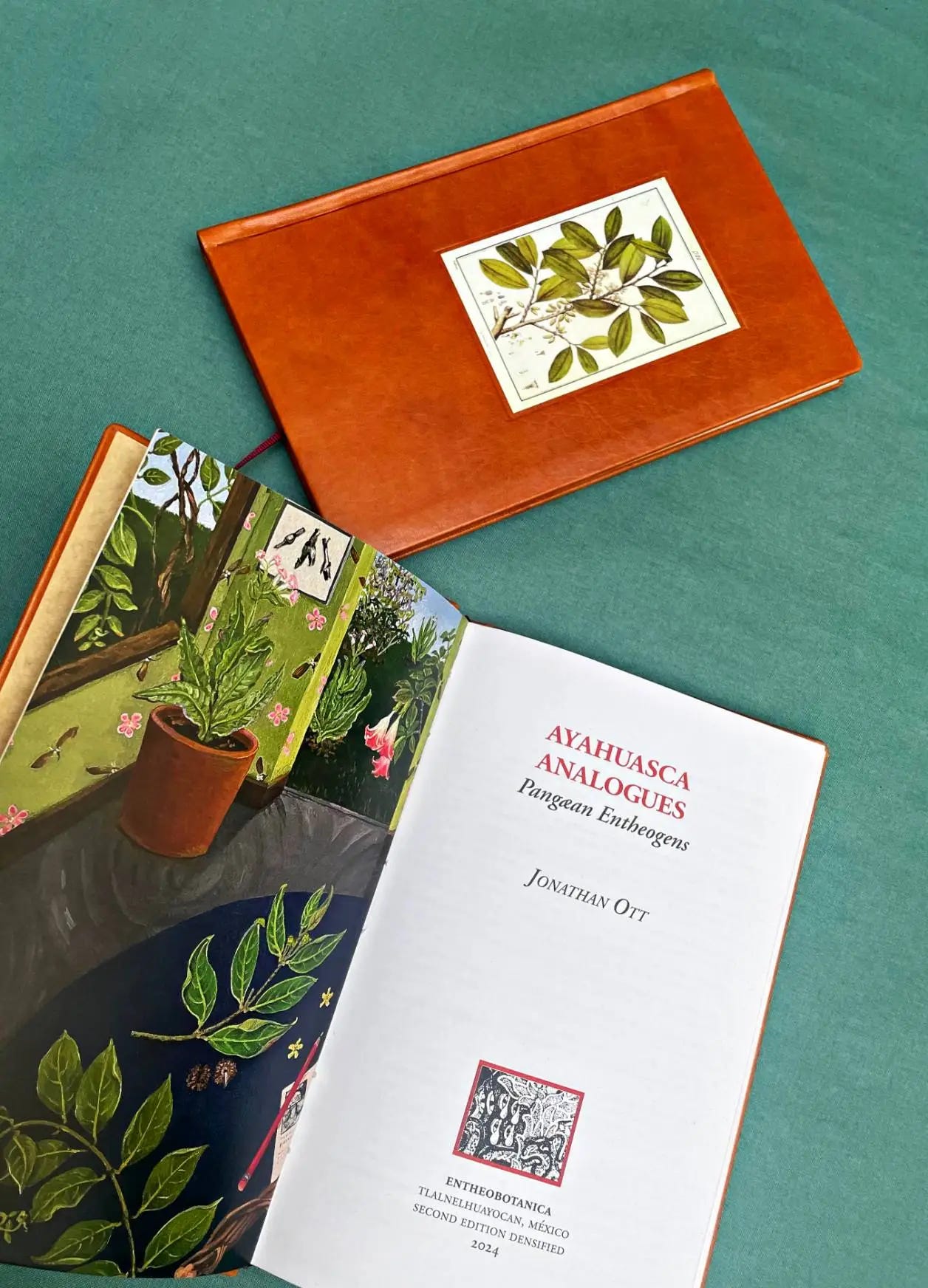

• Jonathan Ott. Close readers may remember that I helped fund the publication of the recent 40th anniversary edition of Crowley’s Little, Big. Another publishing project I am involved in is the remarkable Jonathan Ott Book Series. Ott is one of the great psychoactive scholars, an independent polymath with rigor, wit, an inimitable prose style, and a vast knowledge of drug science, history, and lore. The series combines re-issues of classic works (some long out-of-print) with a few new items. The signed deluxe editions of the first two series titles, Shamanic Snuffs and the classic Ayahuasca Analogues, are beautifully bound in leather with full-color frontispieces and a shared, cloth-bound slipcase. Still available!

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though everything is free here. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.