An enchanting semi-doc about Kazakh eagle-lords

In high school I knew a guy with the Quentin Tarantino-worthy name of Joe Spaid. Joe was more a friend of Wef’s than mine, but we hung out and had some laughs and shared the unusual pleasure of being taught the art of writing by Rosie Sleigh, a wizened crone who sometimes came to class, late, wearing large furry slippers and what looked to be a bathrobe, and in my case did more to pass on the enthusiasm of the written word than any other single scrivener it has been my fortune to encounter.

I’d occasionally run into Joe when I lived in New York a decade later, but we didn’t get together until a year or so ago when, after he pinged me in cyberspace, I visited him and his lovely partner in their apartment in Queens. He had done a vastly better job keeping up with high school cronies than I had, and so I could not keep up that side of the conversation, nor did I have much to say about the impressive reel he showed me of the high-end animation and graphics he makes for TV shows and the like. The evening was engaging though, as Joe possessed an intense good cheer that matched his blazing bright eyes. He told me he had taken a vow against complaining, which made him a bit of an alien to a sourpuss like me but a very impressive and inspiring alien nonetheless.

The other impressive thing about Joe Spaid was the movie he slipped me on DVD-R, an enchanting and gorgeous documentary he had made about the Kazak eagle masters of western Mongolia. Shot on DV over a six month period in full “by hook or by crook” independent mode, and now available online, Kiran over Mongolia has since made the festival circuit, won a couple of awards, and brought Joe and two of the movie’s eagle lords to Dubai. The movie takes place among Mongolia’s Kazak community, a group displaced and isolated in western Mongolia after fleeing the Chinese incursion into then East Turkmenistan. We follow Kuma, a young Kazak man, who takes to the mountains to learn how to capture and hunt with wild eagles, an art known to his grandfather but passed on to him by an amazing, twinkly-eyed wizard named Khairatkhan.

Spaid does not revel in exoticism, and much of the film methodically documents the hard labor of capturing and training Kuma’s eagle. But there is an old-world, almost faery-tale texture to the resulting work, an exotic atmosphere that goes beyond document, as if Spaid and Kuma both found themselves at the edges of some land that time forgot. Much of the magic is provided by the stark and gorgeous mountain regions of this high desert, which are captured with a lyricism I rarely find on DV, whose usually flat and tinny patina is here transformed into a kind of bleak clarity.

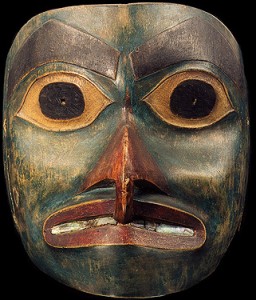

But the real magic is the relationships we see — the relationship between the city boy and the old-school eagle master, and their coupled relation to tradition, and even more the independent bond of humans to eagles. The scene where Kuma captures his first eagle by luring it into a net was one of the more striking nature-doc things I have seen. This is some deep shaman stuff, but practical nonetheless, and one never feels seduced by the vision of indigenous people at “balance” with natural forces.

Far from it in fact. Humans cook the raw: the eagle master captures and constrains the glorious force of an extraordinary bird, just as Spaid creates a fictional frame for these honest and traditional practices. Those of us ingrained with western environmentalism — with its fetish for the wild — half cringe at the sight of these free creatures being captured. And yet, by training this noble and wild creatures these men do not simply dominate and tame, for something of that wilderness passes into them, this old birdlord and this young man. One sees them express less with a sense of mastery than a kind of alliance, asymmetric for sure, but one in which the eagle’s spirit is not only preserved but articulated anew.