May 25, 2008

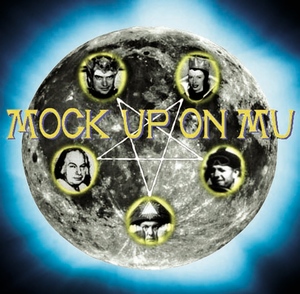

Collage filmmaker Craig Baldwin’s new movie, Mock Up on Mu, is a madcap hyper-meditation on magick and mind control that takes place in a hallucinogenic California spliced together, literally, from B-movies, self-help infomercials, UFO cable access shows, and aerospace promo films. Actually Mock Up on Mu is about a lot of things, too many probably, but the core story it tells—or rather, the story it allegorizes into a SciFi agitprop ADD fantasy—is one of the core narratives of the California spiritual underground: the almost operatic tale of JPL rocket scientist Jack Parsons.

A handsome and hedonistic occultist. Parson performed Crowleyian rituals with L. Ron Hubbard before the latter stole his girlfriend and crafted Dianetics. During his tenure as head of an OTO lodge in Pasadena in the late 1940s, Parsons also hooked up with the mysterious Cameron, a redheaded witch who went on, after Parsons’ mysterious death in a garage explosion, to nurture LA’s young Beat artists in the ways of the wyrd. Cameron upstaged Anais Nin in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and appeared, briefly but with enormous spookiness, in Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide, arguably the first “independent” Hollywood film. Both of these films are key texts in the rich tradition of homegrown California experimental film that Baldwin is very self-consciously sustaining, and both of course pop up in Mock Up on Mu‘s flip-book of sampled images.

One of the key elements of California’s underground aesthetic is assemblage, a post-surrealist collage consciousness that shapes West Coast sculpture (Wallace Berman, George Herms), art (Jess, Helen Adams), film (Larry Jordan) and poetry (Robert Duncan). (I wrote at some length about this tradition here.) Baldwin’s earliest films, like the superb Tribulation 99, were also collage films whose individual elements were painstakingly gathered and even more obsessively recombined from the thousands of reels Baldwin stores in a moldering basement cave in San Francisco’s Mission district. In his more recent films, including Spectres of the Spectrum (which features a cameo from yours truly) and the intellectual property liberation manifesto Sonic Outlaws, Baldwin blends live action with his celluloid patchworks. Mu deepens this development, with actors playing—with varying degrees of success—freely-invented versions of Parsons, Hubbard, Cameron, and Crowley, as well as a craven aerospace defence contractor named Lockheed Martin, played with slithering conviction by activist/actor Stoney Burke.

As a dedicated scrambler of fact and fiction, Baldwin makes no attempt to retell the actual history of Parsons, but instead weaves a SciFi plot that features a moon-based Hubbard sending Cameron on a mission to seduce Parsons and Martin. The resulting combo of live action and assemblage creates what Baldwin calls a “collage narrative,” a phrase he admits is oxymoronic, or “possibly just moronic.”

Moronic it’s not. Mock Up on Mu is an overwhelming experience, an allegorical cyclone of images and ideas haunted by sardonic humor and gnostic longing. Though Baldwin’s visionary splice-mania is less jagged than before—perhaps an effect of Final Cut Pro, used instead of his earlier hand-editing—his samples and juxtapositions have also become more daring and resonant. Tribulation 99 gained a lot of its power through the esotericism of its sources, while in Mu Baldwin refers to better known sources, such as Flash Gordon serials, Star Trek, and, in a slightly more hermetic key, SciFi classics like The Forben Project, Colossus, and The Brain that Wouldn’t Die. One of the themes in the film are the “sticky figments” that Hubbard’s tech claims to clear, the “engrams”—in Dianetics lingo—that in many ways compose our consciousness and perceptions. Baldwin hardly averse to this concept, and recognizes that Hubbard is deeper, though no less twisted, than his detractors imagine. For Baldwin, such sticky figments certainly drive politics, so readily parasitized by false consciousness, and also reveal themselves in our collective cinematic memory—bad movies you can never erase, that you must “forget to remember to forget.”

Though Mu was first shown at the San Francisco Film Festival, Baldwin admitted after one shwoing that the movie has not yet received its final form. Perhaps it never will. The version I saw was certainly too long. And though the collage form demands blazing tangents, a kind of nonlinear explosion of reference, allusion, and theme, Mu went in so many dimensions that by the time you come to the final and most glorious chapters, you are pretty wrung out. (Then again, I had just got off a plane from Paris, so your mileage may vary.) These later chapters, some of which are set to long passages from Parsons’ fascinating and oracular writings, make up Baldwin’s most inspired and prophetic film-making to date. They achieve an almost apocalyptic density—psychedelic to be sure, but not content to simply trip out or dazzle.

The visual logic of magic depends on poetic correspondences, on similes intensified into poetic facts, and in these final chapters, the jigsaw of images and their angular relationship to Baldwin’s themes begin to fuse holistically into a kind of alchemical cinema of imaginative release. At one point, Parson’s sex magick awakens an army of mutants and warlocks, who climb out of underground caverns in order to overthrow the war mongers that now run the show. Make love, not war is their battle cry, and it is not the least of Baldwin’s achievements that this ole chestnut reveals itself, not as a limp-wristed invocation of an old naivete, but a clarion call of judgment against our apathetic age. Baldwin, in other words, ends his film on a courageous note of Romantic rebellion, as the erotic and visionary exuberance represented by Parsons reveals itself as a still living source of energy and resistance to the military-industrial mind control that rules the airwaves.

With the era of Beats and hippies long past, the contemporary pulse of this freak tradition may sometimes be hard to find. Burning Man nurtured it, at least for a spell, but whether Burning Man is a sinkhole or an incubator remains to be seen. Is anything really possible in the bright light of communication? The underground remains a real metaphor, at least for Baldwin, an experimental artist without an idie deal who lurks in his basement lair, surviving what he calls the “masochism of the margins” in order to splice together mutant chimeras of cinematic liberation and loose them upon a zeitgeist whose debt to modern magic, both good and ill, bohemian and corporate, is far stronger than most of us suppose.