Reading the return of paganism

By now, most of us need barely glance over our shoulders to see the cracks and fissures running through the facade of Western Civ. Rationality has degenerated into an instrument of control, science spawns the very problems it then hopes to mend, traditional canons crumble, and the social system that crawled out of Europe’s chilly bogs now munches its way across the planet’s surface like some cancerous machine set on auto-destruct.

For those of us inside this bustling ruin, the crisis of civilization is also a crisis of being. Our identities, forged in no small measure in the smithy of the state, are leaking, and conventional remedies—drugs, therapy, materialism, distraction—are just so many buckets. Identity must itself be tinkered with, unfolded, perhaps rekindled. And the first thing that needs major tweaking is our monotheism of mind.

Wait a minute. Isn’t God dead? Perhaps, but his chattering skull lives on. For what is the righteous ego if not our own personal Yahweh? Jealous of the other figures of mind, locked in his panopticon, armed with a Cartesian camera, this self-serious tyrant demonizes the pantheon of moods in the heart and the packs of beasts in the body. Left to its own devices, the ego becomes demiurge, breeding dualisms left and right, clutching a single tragic vision that divides the self from the dreaming world and kills that world in the process.

The unhealthy dominance of the ego calls for a cure, but obviously not the violence of surgical removal. Totalizing solutions are just more commandments, born-again delusions of a clean-slate self. Instead we need a complex, gradual disintegration. The Jungian renegade James Hillman suggests a polytheistic psychology. A cranky and oddly classicist postmodern of sorts, Hillman rejects the Jungian notion of a unified self as a humanist crock, while still accepting the psyched as a field that can be deepened into a collective landscape of imaginative resonance. “What we now all the unconscious are the old Gods returning, assaulting, climbing over the walls of the ego,” Hillman says. Rather than foment schizophrenia, this revival expands the self into a fluid and grounded multiplicity of styles, rhetorics, and drives, thickening the texture of interior life while simultaneously unfolding the self into the body, the street, and the field: no longer an alien master of dead matter, but a polymorphous Pagan in an awakened world.

But cures never work in the mind alone. They must be expressed and performed, and for at least three decades, all across the country, folks who have never read Hillman (or visited California) have been putting polytheistic remedies into practice: WASPs raised on Bewitched cast ritual circles, Jews invoke the Canaanite fertility goddess Astarte, systems analysts worship trees.

These Neopagans—or Pagans, as they increasingly call themselves—seek to live in a world in which, as Euripides said, “all things are full of gods.” To do this they must not only crack the mundane ego, but bootstrap the imagination, our distinct faculty of resonant perception. As children, all of us possessed a

certain eye that glimpsed gnarled faces in rocks and clouds; Pagans seek to recapture that mode of liminal awareness, conjuring it our of the body with ritual and trance and magical visualizations.

Half a century old, larger than the Unitarian church, Paganism is no fad. As Chas Clifton writes in his introduction to Witchcraft Today: The Modern Craft Movement, the Craft “presents a radical critique of the dominant forms of spirituality more than it seeks an accommodation with them.” Wiccans—and the more inclusive category of Pagans—reject scientism, dualism, and the pure drive for escape velocity found in many transcendental Eastern paths. And though Pagans root through the New Age grab bag of positive thinking, alternative medicine, and Gaia talk, the movements chafe more than the sing: while well-heeled New Agers float in a diaphanous haze of “higher frequencies,” the far more bohemian Pagans ground the spirit in, as, as Clifton puts it, “dirt and flowers, blood and running water, sex and sickness, spells and household tools.”

The boldness of Paganism’s revisionary religion—as much a subculture as a system of worship—has swollen its ranks with the marginalized, the progressive, the weird: feminists and soldiers, lesbians and gays, SF fans and computer programmers, eco-hippies and Jews, garage scholars and the sword-wielding medievalists in the Society for Creative Anachronism. While any given Pagan festival—imagine a clothing-optional occult Renaissance Faire where everyone is in character—will turn up a wide mix of druids, Radical Faeries, and “Episcopagan” ceremonial magicians, witches (or Wiccans) increasingly dominate the movement. Most Wiccans work, with varying degrees of slack, within the tradition cobbled together by retired British civil servant and nudist Gerald Gardner in the 1940s: small covens that cast circles on full moons, dance and chant, and invoke a horned hunting God and a Triple Goddess.

While some “trad” Wiccans remain surprisingly insular and conservative—especially for folks whose rituals include nudity, flagellation and mild bondage—feminism and the anarchic strain of American spirituality

have now produced far more “eclectics:” loose-limbed and more improvisational witches who sample from many traditions—and generally bag the scourges. And though generalizing about such a ragtag crew is like painting a rainforest with one shade of green, it can be said that all Pagans, recognizing humans as little more than animals with particularly swelled heads, seek to plug themselves into the imaginative and energetic matrix of nature. But while Pagans lose themselves in ritual, they simultaneously recover themselves in the folktales, relics and bloody testimonies of Indo-European history.

***

When secular intellectuals hear the words “European folk culture,” most reach for their revolvers, remembering how successfully Continental fascists juiced up the masses with appeals to intuition and peasant values. But such reactions say more about a common intellectual paranoia in the face of mythic thought and experience than they do about the intrinsic politics of occult spirituality or nature mysticism. Besides, with the exception of an isolated pocket of racist Vikings, fears of reactionary irrationalism are belied by what Pagans actually say and do.

Far too antiauthoritarian to brook fuhrers or gurus, Pagans use historical materials to cure themselves of historical determinations, and to tape the underground streams murmuring beneath the dominant narratives of the patriarchal state. Histories of the Craft invariably invoke the Inquisition, and images of conflagration haunt many Wiccans. Though often inflating the death toll of “the Burning Times” to Holocaust proportions, Wiccans use this historical echo to create an intimate connection among the underdogs of Europegays, women, heretics, the poor, Gypsies, Jews. And, with the exception of the Romany, all these groups are well represented in the Pagan revival.

By identifying with their pre-Christian ancestors, the white folk drawn to the Old Religion are performing a Euro-American equivalent of Afrocentricity. For they consider themselves yet another group colonized, then demonized, and now misrepresented by the powers that be. It’s no accident that the Celtic lore of Ireland—the most popular European tradition for Neopagans—belongs to one of Europe’s most downtrodden peoples. Besides their legitimate concern to distinguish witchcraft from Satanism, some contemporary witches condemn the evil hags and sirens of Halloween and Disney with all the earnestness of campus crusaders. And most Pagans are highly sympathetic to the struggles of people of color—and not just because many Native Americans, West Indians, and Latins are struggling for their gods as well.

Pagans thus navigate a powerful route between bland white liberal guilt and Caucasian appropriations of nonwhite cultures, whether Rastafarians, Indians, or Santeristas. Pagans thus create a margin of white authenticity from which to proclaim a critical religious and social counter-history of the West traced, like the Black Mass, backward: from the Christian devil to the horned Pan, from the early church to the mystery cults, and from ancient polytheists all the way back to the Stone Age haze when only the Goddess reigned.

All this leads to a highly combative use of history. In his feisty and fascinating Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture , Arthur Evans admits that because his heavily footnoted history of gay sex, heresy and rural magic concerns “the victims of Western civilization, rather than their rulers,” his book is one-sided, subjective and arbitrary as to sources. He further points out that all historians work this way. Of course, shit like this really riles academic scholars, but what stands out most in their intellectually legitimate critiques of Pagan revisionary history is not the sharpness of the bones they pick but their snide and arrogant pleasure in the process.

But the conflict goes beyond a turf war between professionals and garage scholars, into the thorny issue of the role of speculative imagination in our understanding of history. Europe’s Pagan residue lingers in the shadows of recorded (Christian) history. Any Pagan revisionist must also raid the worlds of mythology and poetic intuition, uncorking alembics of spirit in history’s dusty labs and transmuting the chemical record of the past into an alchemy of meanings.

Nowhere are the curious consequences of this alchemy more evident that in the work of archaeologist Marija Gimbutas. In the mid-70s, Gimbutas began using pots and figurines to construct a tale of an Old European matriarchal partnership society that worshipped the Goddess and lived in peace until around 6000 years ago, when marauding Conans and their macho sky gods came thundering in from the east on their excellent horses. Though clearly an eco-feminist Eden myth, Gimbutus fuels her speculative fire with a mass of research and comparative myth, and this tension between facts and an imaginative use of folklore makes for fascinating reading.

Gimbutas cleared the space for the Goddess movement to flourish, though the seeds were first sown by British revivalists like Gerald Gardner, feminist witches like Z. Budapest (who formed the Susan B. Anthony Coven in the early ’70s), and Starhawk, whose great The Spiral Dance galvanized the Craft with its pragmatic link between progressive politics and a no-bullshit grasp of magical techniques.

But where Gimbutas leaps, many of her followers veritably fly, and much of the Goddess phenomenon now stands apart from Paganism proper. In the hands of some feminists, the polymorphous Goddess of flux crystalizes into yet another totalizing, and essentially monotheist, ideology—what Morning Glory Zell calls

“Jahweh in drag.” While it’s fine to experience such disgust with civilization that you reach back to the Stone Age for an image of the good life, this backwards-masked mode of ecological and patriarchal critique often settles into simple therapeutic catechism. Though the best Goddess books rattle their archaic evidence like curing fetishes, recovering the Goddess from the dust of pre-history often becomes the archaeological analog of recovering your inner child.

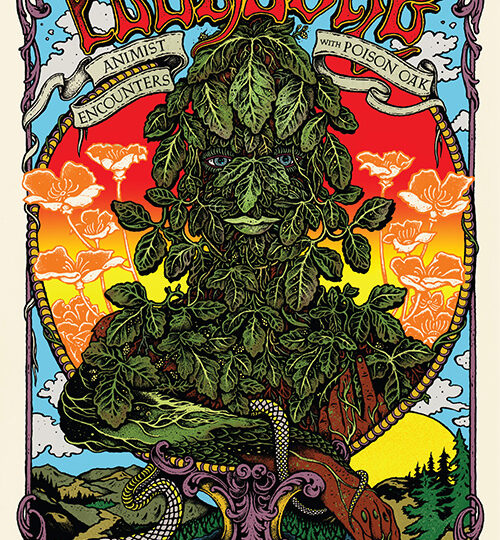

While too many Pagans and Goddess authors lapse into literalism and strident claims of authenticity, many also recognize that the creative force behind their revisionist stories is not truth but the polymorphous reflections of their own shifting perspectives. Strong polytheism allows fabrication and authenticity to dance without destroying each other. And when you set out to straddle the dry shores of facts and the swamps of mythology, or try to channel the oral ghosts which haunt the written word, distortions both clever and careless arise. But so what? History’s a Rorschach blot, and the gods peer out of your eyes. Can you see the vulva in a standing stone? The horns on a jester’s cap? The Green Man in the corner of a church? Or the goddess that surveys New York’s harbor? A funny thing happens when you start looking for the winks and signatures of these furtive figures. They start looking for you.

***

Though Paganism prides itself on rejecting holy scripture for immediate experience, it remains in many ways a religion of books. Surveys confirm that, as the witch Heather O’Dell put it, “most people drawn to the Craft are addicted to reading.” And many are also drawn to it through reading—not just classics like Janet and Stuart Farrar’s What Witches Do or Margot Adler’s Drawing Down the Moon (which remains the best social history of the American movement), but through fantasy novels as well. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Mists of Avalon, a feminist revision of the Arthurian mythos, may have hooked more witches than Starhawk, and Pan only knows how many druids were born with the words “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

Avoiding the ossifying reaction of academic traditionalists, the tiresome fugue states of theory, the glib ignorance of the New Age, or the ironic capitulation of TV addicts, Paganism finds its postmodern soul in the crepescule between dream and text. Many critics have noticed that for all the rhetoric of “information,” our age demonstrates the triumph of image over the word, the dissolution of intellectual coherence into a sea of simulation. But Pagans have their cake (and ale) and eat it too, and not just because magic has always been a science of simulacra. Pagans know that words feed images. In a sense, Pagans read Gimbutas, The Mabinogion, and Mircae Eliade the same way they read comic books, Carl Jung or Ursula LeGuin: with a strange combination of wonder and pragmatism. They want that buzz, that mythic resonance that sets the spine ablaze, but they’re also on the prowl, ready to poach maps, chants, and god from the texts at hand.

Modern witchcraft began not with a revelation or an initiation, but with reading and rewriting. Though Gerald Gardner claimed to have contacted a secret New Forest coven whose tradition stretched back centuries, the Craft scholar Aiden Kelley and others basically proved that Gardner’s system was basically fabricated. Gardner cribbed much of the ritual from the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley and the American folklorist Charles G. Leland, whose wonderful Aradia collects the spells of a late-19th century Italian Dianic cult. Gardner also heavily borrowed from the historian Margaret A. Murray’s 1921 The Witch-cult in Western Europe, which took somewhat Gimbutus-like leaps to argue that witches’ sabbaths were actually pagan fertility rites and the devil a man dressed as a horned god. Like Robert Graves, whose White Goddess also strongly influenced British Wiccans, Murray wove a tale from folklore and fact. But to Gardner and others, these historical poems rang true, and though subsequent work by Carlo Ginsberg and others has shown Murray’s essential intuition to be correct, most witches today owe their existence to what was in some sense a literary resonance.

Which is why my favorite Pagan origin story is not Gardner’s New Forest initiation but the birth of the Church of All Worlds at Westminster College, Missouri in 1962. Undergrads Lance Christian and Tim Zell were obsessed with Ayn Rand and Maslow’s self-actualizing philosophy. Then they read Robert Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land, which described the communal non-monogamist Church of All Worlds founded by the Martian exile Valentine Michael Smith. Grokking their deepest desires in the SF text, the two students and some female friends performed Smith’s sacred water-sharing ritual, hopped in the sack, and founded a church. Later Zell renamed himself Otter, penned a prescient form of the Gaia hypothesis, and started using the word “Pagan” to describe CAW’s increasingly earthy and eclectic religion. As Zell recently put it, “we’re a sequel to a myth that hasn’t even happened yet.”

Cobbling together new Old Ways, Pagans proceed by a curious process of memory and forgetting: first, remembering the broken limbs of the gods scattered in books, museums, and nursery rhymes, then erasing those mundane sources into a vast memory of practices which simulates the timelessness of oral transmission. Most Wiccans don’t have a clue that one popular midsummer chant is an adaptation of “A Tree Song” by Rudyard Kipling. Or if they know, they don’t really care, because for them the chant works.

Their emphasis on pragmatism may seem paradoxical to some, but Pagans are more positivist than you think—they just expand their definition of admissible evidence. Such this-worldliness explains why occult shops (and botanicas) are as much like hardware stores as book worlds: the candles, swords, bowls, cards, talismans, jars of herbs and incense, all asked to be used. And much of the printed material consists of reference tomes or how-to books like Scott Cunningham’s popular Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner, which includes basic rituals, descriptions of tools and altar set-ups, and recipes for incense and “crescent cakes”. Most of these manuals are rather slight variations on a basic theme, and frequently lapse into the simply superstitious, forgetting the words that close the lovely Charge of the Goddess in the Gardnerian liturgy: “if that which you seek, you find not within yourself, you will never find it without.”

Still, these Wiccan cookbooks invest their religion not with dogma but with lore—the customs, hints and hand-me-downs that help Craft the magic into ordinary life. Rather than the ponderous intonations of ceremonial magic, this kitchen witchery blurs the distinction between herbal remedies, Gramma’s cooking secrets, and the secret ingredients for a Full Moon ritual anointing oil. Reflecting the fact that most Neopagans are city-folk, Patricia Telesco’s The Urban Pagan include lots of handy ecological tips for apartment dwellers alongside self-help visualizations and herbal cures. Her chapter “The Frugal Magician” includes designs for popsicle stick pentagrams and a discussion of “techno-magic” using computers, microwaves and TVs—which, when turned off, apparently make good surfaces for scrying.

Telesco’s massive attempt to reimagine the alienated objects in the urban field stands as a testament to the Pagan urge to sacralize and imaginatively deepen the world by whatever means necessary. Clearly, these techniques, a kind of magical pop art, extend beyond the recovery of rural folkways or naive Romanticism. So what’s going on? In describing the options of the individual within the technocratic state, Michel De Certeau unintentionally nailed the tactics that underlie Pagan practice: “Increasingly constrained, yet less and less concerned with these vast frameworks, the individual detaches himself from them without being able to escape them and can henceforth only try to outwit them, to pull tricks on them, to rediscover, within an electronicized and computerized megalopolis, the ‘art’ of the hunters and rural folk of earlier days.” That art is natural magic.

***

The hands-on aesthetic of Pagan spirituality carves a postmodern peasant religion from a world of unseen but ever-present landlords. Yet a strong millennial strain courses through the movement, an apocalyptic urgency not grounded in Christian eschatology but in a frank assessment of our ecological crisis. Healing the soul of its imaginative anomie and the body of its rigidity becomes analogues to healing the earth. Pagans recognize that rules and regulations alone cannot alter attitudes toward nature that are welded to civilization at least as securely as sexism is. The belief that humanity lords over the biosphere as its master and finest product is a function of the structure of Western consciousness, a structure that Pagans attempt to erode with art and ritual and enacted imagination.

Still, apart from psychedelic aficionados, the environmentalist fringe, and a few cool comic books, the link between Pagan imagination and deep ecology remains confined with a rather hermetic subculture that doesn’t proselytize or sell itselfand may party more than it should. Pagans do draw folks into their world, but that world is itself conjured on the fly: festivals and ritual circles are said to be “between the worlds,” spaces cast and then collapsed (or “opened”) like a psychic nomad’s hut. Along with the few islands of Pagan-owned land, Pagandom consists of a shifting network of temporary autonomous zones and the virtual communities created through computer bulletin boards, online discussion groups, and, most the exchange of zines.

Pagans currently produce over 500 periodicals, a tremendous output for less than half a million people and one that underscores the centrality of writing to Pagan experience. The Crone Chronicles reclaims the figure of the Crone for older women, while the teens that put out HAM cater to the growing crop of Pagan kids. The increasing influence of gays on Paganism can be felt not only in ongoing debates about gender and magical polarity but in zines like Out of the Broom Closet and Coming Out Pagan (the latter of which noted that the obviously pagan Ice Man found in the Alps a few years ago had traces of sperm around his anus). But the Church of All World’s Green Egg remains the great Pagan publication: besides unearthing old gods and birthing new ones (call on Squat the next time you need a parking place), and Green Egg‘s Readers Forum remains the best print intro to the fractious, funny, sexy texture of Pagan community.

Just as Pagans see our species as inextricably and joyously embedded in the matrix of the earth, they also view the human soul as immersed in collective experience, a carnival of dark mothers, gay centaurs, vengeful redwood sprites and cyberspace tricksters. A most postmodern archaic turn, one that suggests that the death of the subject may have been announced prematurely—the self did not die, it just slipped like Persephone into the underworld. The babbling surreality and fragmentation of contemporary culture not only signify the collapse of the West’s sun-bent master narrative, but the return of the tales of a thousand and one nights. And that’s why you make a friend of the moon.