With some excellent and kind help, I am currently in the midst of a massive revision of my Techgnosis archive site. This has sent me back to my own earlier work, much of which doesn’t appear on that site. One entertaining thirty-year old piece I just came across on an Aphex Twin fansite was the March 1994 feature I wrote for Spin about the “See the Light” tour that took place in the US in 1994. Featuring Orbital, Aphex Twin, Moby, and a lesser-known act named VapourSpace, the show was an attempt to communicate underground rave culture—which had been bubbling up in the US since the beginning of the decade—to more mainstream audiences. I had a fun time with this one. While I wish I had chatted more with Richard James, who spent most of the time stoned in the back of the bus, I enjoyed talking with Moby and especially hanging out with the friendly Orbital boys. Writing-wise, it’s me in full rock journalist mode, but the piece also resonates in interesting ways today, given the triumph of EDM and the digital remastering of psychedelic dance culture.

DENVER, COLORADO

Tuesday is a lousy night for a rave. But when you’re touring the country, you can’t just play weekends, and so the four techno acts on NASA’s See the Light bill —Moby, Orbital, VapourSpace, and Aphex Twin—are playing tonight for a couple hundred people. It’s a school night, so there aren’t too many kids, just a motley flock of hooded sweatshirts, Deadhead tie-dyes, fractal T’s, and blue jeans. No conspicuous druggy hugs or candy-cane Dr. Seuss hats are in evidence, though one rather puzzling blond is dancing maniacally in a costume apparently made of tinfoil.

See the Light has a tough charge: to bridge dance floor and concert hall, mainstream and underground. Raves depend in part on faceless DJs playing faceless tracks in a space where lights and darkness and overwhelming beats put you, in the words of NASA’s computerised lights-maestro Scotto, “in a trance without tripping.” So when VapourSpace takes the stage of this rock club, his juicy “Gravitational Arch of 10” squonking like a Sega Genesis tangerine dream, he’s definitely aiming to transport. But for many in the crowd, it’s hard to achieve rapture while watching a short, bespectacled fellow with long scraggly hair diddle a stack of machines.

When Orbital arrives, it’s even more anonymous: Two bald heads bobbing over buttons and LEDs in the shadows at the edge of the stage, strapped with flashlight goggles that make the Hartnoll brothers look like the Jawas in Star Wars. Darryl, the twentysomething editor of Scene, a local dance mag, approaches me and gives me the scoop on, well, the scene. “Raves have become a place where bored kids can go to hang out and do drugs,” he says. “The interest is growing but the scene is dying.” But he was in awe of Orbital. “What they’re doing is much more difficult than a rock band. It’s like a one-on-one war with technology.”

In many ways this is true, and as I watched the rotating lineup night after night, I came to appreciate the subtleties of improvising with samples and sequences. But while rock sweats and grinds, these musicians jam in an abstract realm of circuitry. I was following the dancing pulses on the large oscilloscope Orbital projected above the stage, when this Hispanic DJ named Positive Vibe leaned over and screamed. “It’s like watching somebody die at the hospital. If they had more DJs it’d be a rave, but call it a tour and everyone stands around staring at the stage expecting a show. This music’s so much cooler at home, kicking back and smoking a joint. All it is is Pink Floyd again, and at least Pink Floyd gave you a show. They tore down the wall!”

Moby, America’s best-known Christian techno vegan, tries to tear down that wall. Onstage he radiates an innocent hedonism, making eye contact with the audience, exhorting the crowd to dance, and assuming a dramatic crucifixion pose as Scotto’s Intellibeams build to a strobing apocalypse. Then he’s running around the stage, smashing out beats on an octapad, thrashing an electric guitar, his joyful noise rousing the crowd into a frenzy.

Accessible and intense, Moby’s performance was the most enthusiastic spectacle of the evening. But though he included a live drummer (along with a suspiciously superfluous second keyboardist), Moby has used playback DAT tapes rather than “live” sequencers to reproduce parts of his music. This sacrilegious use of canned tapes proved to be the controversy of the tour, causing grumbling on the bus and nasty Moby-bashing posts on the Internet computer newsgroup alt.rave—though many of the latter were responding to Moby’s own post, in which he called some of his critics “anal-retentive fucks who would be better off writing critical analyses about Emerson, Lake. and Palmer records.”

When I ran into Moby backstage, he was bumming out. He had just read the latest batch of flames, which Lane, the tour manager, had downloaded from a hotel phone line into his Powerbook. “At the risk of sounding bitter, I kinda feel that someone’s moved into the house that I built and kicked me out.” Moby used to dis people using DATs, so he’s trying to chalk up the bad vibes to karma, but that doesn’t change his new attitude. “For me, there is no difference between hitting play on a sequencer and hitting play on a DAT machine. It seems so arbitrary given the type of programmed music we’re talking about. A much more valuable criterion for me is: Did I enjoy the music, was the performance sincere, was it a transcendent experience? I used to do everything live, and all I know is that now my shows are more entertaining.”

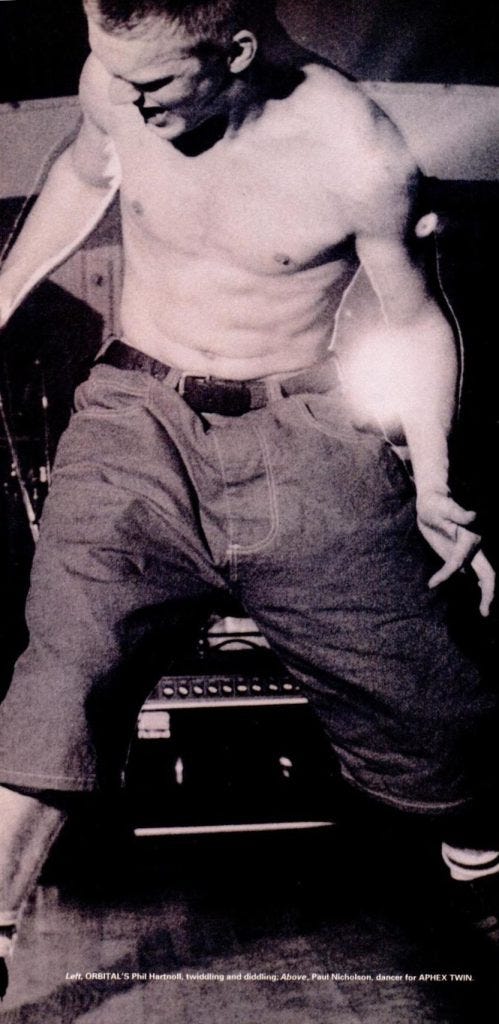

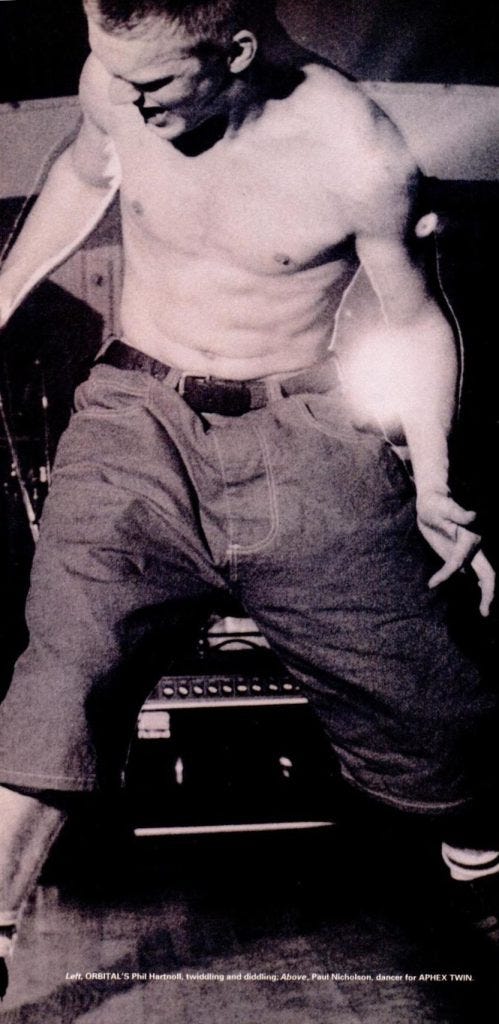

Then the ominous rumble of Aphex Twin begins. A well-chiselled Aryan walks onstage and begins dancing like an off-world android fast-forwarding through a Tai Chi routine. But this isn’t one of the Aphex Twins. In fact, there are no twins, just a scruffy 22-year-old Brit named Richard James, who’s kneeling on the floor behind the dancer in a shadowy tangle of wires, patch cords, and fat bubble wrap, surrounded on all sides by hacked-up contraptions. Aphex Twin’s home-brewed machines emote some of the most achingly beautiful and alien soundscapes in music today, electronic creations that soar above the rising tide of ambient or “intelligent” techno. But tonight is not an ambient night. From his nest, Aphex Twin lobs sonic grenades at the crowd’s lower chakras, while his white noise practically scrapes my inner ear. A light piano melody flutters like snow over a massive bass beat, and in my mind’s eye I see huge chunks of glacial ice crashing into a frozen Northern sea. Then my mind’s eye melts.

HIGHWAY 285, NEW MEXICO

No one’s sure, but they think the last rock journalist to ride the bus may have committed the ultimate touring sin and left a turd in the john. But it’s proved a dependable source of humor, just like asshole jokes, Milo the bus driver’s tall Texan tales, and the mutual mimicry of Brits and Yanks. ” ‘Ello guv’ner, ” is our refrain. For their part, the Brits like snapping photos of the desert. And the used-car lots.

Moby doesn’t ride the bus. He says it’s because he’s allergic to cigarette smoke, but if this almost masochistically moral person was consciously avoiding rock ‘n roll excess, he didn’t miss much. Lane has stocked the fridge with soy milk and baked tofu, and the only visibly addictive substances on the bus was a Nintendo Game Boy. One of the Orbitals misses his wife and kids, and except for a second hand report of a potential blow job, the pleasures of the flesh seem to be limited to “spliffage.” As DJ Tim says, “Techno bands don’t get underwear thrown at them. They get computer disks thrown at them.”

As the bus winds through pockmarked New Mexican Hills, the curious European combination of Drum and weed fills the backroom. Richard James plays chess, while the drop-out who sells T-shirts flips through Japanese comic books and Micky the Scottish soundman rifles through the videos (Willy Wonka, Star Trek, Ren & Stimpy). Staring out the window at the passing desert while the crystalline ambient beats of Reload flow from the tape deck, I suddenly grok how nomadic this headier techno is, how smoothly it glides and expands into the solitude and wordless communion of the wide-open spaces outside.

Of course, the ultimate wide-open space is inside your brain. “Before, techno was totally conducive to clubs,” says Orbital’s Phil Hartnoll. “Now it’s getting into people’s heads.”

“We all see the abstract world when we close our eyes.” says his younger brother Paul. “I used to do it when I was bored at assemblies at school. I’d sit there and push my hands to my eyes and I’d see shapes and colours and images. And then one day I took magic mushrooms and I thought, wow, I don’t even have to press my palms to my eyes anymore.” He takes a bite of his peanut butter sandwich.

“When we’re in the studio, we plinky-plunky around till we get something that we like,” says Phil. “It’s like going on a journey. It’s hedonistic, really.”

We pass through Roswell, New Mexico, the site of a famous UFO incident. In 1947, the Air Force had reported recovering a “crashed flying disk,” and rumours of alien corpses and cover-ups have been gurgling ever since. Orbital has heard those rumours.

“There’s obviously something, mysteries untold, beyond this planet,” says Paul, who tossed a sample from a dubbed French alien conspiracy film into the Orbital 2 cut “Impact (The Earth Is Burning).” “I often think of electronic music as UFO music.”

When Orbital flew to Australia for a New Year’s Eve party, Paul stayed with a local DJ. “One of the first times we went out, I bought a T-shirt with flying saucers on it that said, UFO’s ARE REAL. We talked about our track ‘LC1,’ which sampled a woman on a game-show talking about her alien abduction experience, and he started asking me about corn circles.” Soon after, the DJ went to Goa, a techno-hippie Mecca on the West Coast of India, and lost it. “He took far too strong a dose of LSD and started running around naked and trying to drink puddle water. He thought that everyone was part of this big conspiracy. He started making all these connections with me, that I knew something, something to do with outer space, and that I was trying to initiate him into the group by buying this T-shirt, by doing the track, by talking about corn circles.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that this conversation eventually leads us into a metaphysics—specifically, whether or not Star Trek: The Next Generation is better than the original Trek. “Isn’t old Jean-Luc Picard much nicer than Captain Kirk?” Phil argues. “I want to be Jean-Luc.” he adds, perhaps explaining his shaven head.

“I could settle for Data,” his brother adds.

“Jean-Luc for me. ‘Make it so.’”

CARLSBAD CAVERNS, NEW MEXICO

The tour takes advantage of a day off to visit Carlsbad Caverns. As we pass through the yawning cave mouth, we’re each given a handheld radio device that sputters out data on the caves. Richard James tries to wrap the thing around his head. Then we’re wandering past monstrous dripping ghost stones, our wet footsteps echoing off into space, and the radio mentions how people “use their imaginations to find images in the formations.” That’s what I do when I listen to Aphex Twin, so I prod James about how you can see different shapes in the rocks: whales, faces, castles. He looks about. “Yeah. And cocks.”

Richard James likes caves. His dad was a miner, and one day they explored an abandoned mine and found old hats and trains and hobnailed boot tracks in mud a century old. As a kid, he and his friends played games in the caves along the coast of Cornwall; games like “getting lost and trying to find our way out again.”

James is glad he grow up in isolated Cornwall. “Although there are lots of commercial things to do in the city, you don’t have to make up things for yourself, which I think is so much more gratifying.” When he and his friends first heard about raves, they had to throw their own. “They ended up being the best ones I’ve ever been to. We used to do them on secret coves along the coast and behind sand dunes. Get a generator and a UV light and plug it in and then just walk off into darkness and set up.”

When acid house hit his isle, James had already been making electronic music for years. “Since being pretty little, I was always taking things apart and making noises with them. When I was ten, my parents got this old piano. I played on it for a while and then I took the back off and realised that around the back was much more interesting. Made much scarier sounds. So I turned it ’round and started doing stuff to the strings, wedging stuff under them, and detuning them.” He moved onto pawn-shop tape recorders and ghetto-blasters scavenged from dumps. “For me, fucked-up machines are just a means of getting more interesting sounds.”

Now he’s obsessively driven to conjure alien drones, galactic surf, and static rainstorms out of his homemade gear, as captured on his haunting Selected Ambient Works Part II. “I could go out and start making things out of pipes and bits of wood, but it would be so slow compared to building circuits. Electronics are so fast. You don’t have to wait for the band members to get out of bed. For me, the main problem is that I get too many ideas and my mind sort of jams up.”

James definitely has an odd mind. He sees each of his hundreds of tracks as different shades of yellow, and he takes the physics of sound personally. “When I was 17, I really got into sampling and analysing sounds. At first I thought, like, a bird sound is a bird sound, a dog is a dog, a whale is a whale. But then I discovered that they were all just variations on a sine wave. It’s just the way that wave was used that made it sound specific to that thing. That really pissed me off. It’s like there’s only one sound in the world and everyone uses it, just in different ways. I don’t know why, but it just pissed me off. Then I realised that that’s the beauty of it, because it’s how you manipulate that basic sound that makes something different.”

Like DJs with their rare grooves, techno wizards like James base much of their originality on manipulating information in clever ways. This lends techno an esoteric air, which in turn has spawned a small subculture of anal baseball card collector types who track obscure import only remixes and analyse arcane twiddlings. Aphex Twin devotees are some of the worst. “With most bands everyone just jumps about and doesn’t really think about it, but I’ve got these sad fuckers who stand in the crowd writing everything down.” Not that he particularly likes the crowd dancing to his music. “I prefer it when people stand around.”

So you don’t really enjoy communicating with your listeners?” I ask.

“It’s amusing hearing what tracks people like shagging to, but I don’t care what people think. I could imagine Moby saying things like that, but it’s all just bollocks to me.”

EL PASO, TEXAS

“I have a desperate need to communicate with people,” Moby says, sitting on a crumbling couch in a room above El Paso’s Club 101. “I was brought up an only child, in a strict Caucasian upper middle-class culture. I’m fairly shy and I work by myself exclusively. All this drives me to communicate.”

He seems to be succeeding. Earlier that evening, Moby had been standing around near the T-shirt stand during VapourSpace’s set. A scrawny white kid in a desperately hip Psychick Warriors Ov Gaia T-shirt picked up one of Moby’s “READ ME” fliers, and read the man’s intelligent attack on the National Rifle Association, animal testing, and cigarette companies. “I agree with the first two but not the last one, ’cause I smoke,” he told his friend. Then a brown-faced girl asked Moby for an autograph. He scrawled his signature and a little cartoon of himself on her T-shirt. A line of Mexican-American kids with striped stocking caps instantly formed. One girl squealed. Moby smiled shyly.

Earlier, Moby had spent his afternoon hunting through town for a decent vegetarian restaurant. The tour has been rough on his strict vegan diet (vegans don’t eat eggs or milk products), and he misses his juicer terribly. “I even love cleaning my juicer, getting our the toothbrush and scrubbing it. Nothing is more psychologically and physically comforting than fresh juice. I feel like all my cells are happy with me.”

Moby’s rigorous veganism fits with his personality, because while he craves communion, Moby is also a man whose high standards set him apart. As a teenage punk in Darien, Connecticut, he railed against society with his band the Vatican Commandoes. In his late teens, he stopped drinking and doing drugs, became a vegetarian and a believer in Christ, and started making dance music. And now he rails against political and ecological ills, puts disco divas and electric guitars in his techno songs, and refuses to ride on the bus. “I intentionally do things to antagonise people in a very ambiguous way.”

Moby admits that there’s a secret link between this iconoclasm and his desire to follow Jesus. “They’re symptoms of the same thing. One thing I really like about Christ is that you can never be complacent. He’s always turning logic on its head. The only people he has anything bad to say about are religious people, and he hangs out with prostitutes and tax-collectors.”

When Moby first started squeezing techno tunes from his machines, he loved the fact that rave culture wasn’t personality driven. But now that facelessness has become de rigueur, techno’s least anonymous figure wants more from the music he loves. “I’m really missing the adolescent feeling of getting excited about a performer and a personality.”

Ask Moby why and he’ll give you some of the best “pretentious rock ‘n roller theory” you could hope for from a pop star. “The industrial revolution effectively separated human beings from those institutions that made humans satisfied: a sense of community, a strong sense of family, a connection with your work and creativity, and a good relationship with God and the land. One of the reasons people need personalities nowadays is that it’s a way of achieving intimate communication.”

Another last-ditch mode of communion is dancing. “Raves are basically people getting together in a dark place dancing together with lights in their eyes. Forty-thousand years ago people banged on logs in front of a fire and it was basically the same thing.

“Dance culture is sexy and, at it’s best, decidedly un-Caucasian. A disco record threatens a white guy ’cause it makes you want to dance, to be vulnerable. I find some woman singing ‘You make me feel so good’ a million times more intellectually satisfying that an Elvis Costello song. It’s the same way I find going to the ocean and being impressed with the vastness and grandeur of nature a lot more intellectually satisfying than reading a poem by Yeats.”

In a mediascape bloated with stars who attempts to cure their bad consciences with good causes, Moby’s hard-ass self-examination and rigorous regimens makes his rants not only tolerable but inspiring. “I make myself an example. I’m not a great example—there’s lots of glaring inconsistencies and hypocrisies in my life—but I’m admitting that. Everyone needs to accept responsibility to try and change themselves if they want the world to change. Capitalism is a failure. The earth is being destroyed to perpetuate a system that’s not making anyone happy. The only threat to humanity at this point is humanity. And hurricanes.”

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

The tour’s final show goes down in the postmodern atrium of La Galleria, a cavernous, leafy space with exposed elevators that serves as the fashion design centre of San Francisco. The soul of this city has long fed on frequently nebulous visions of virtual reality, LSD, Zen, brain machines, and pagan tribalism, and raves have become a vital carrier wave that focuses and redefines all those disparate signals. Here the overtly ritualistic impulses within techno are blossoming, with British ambient DJs, psychedelic graphic designers, Genesis P-Orridge, and white techno sadhus from India all making the scene.

So full of surfaces that it becomes profound, this is a scene that is seen. On a variety of large screens hung above the dance floor, the San Francisco video crew Hyperdelic extruded an iridescent ectoplasm of alchemical diagrams, alien sunsets, and molten pixels, while NASA’s psychecyberadiant lights etch pentagrams in the haze rising from joints and Krishna incense. Mutants on parade: a gay skinhead with a Shiva T; a legendary telephone hacker named Captain Crunch; a woman pierced and rapturous and covered with Day-Glo paint; a scruffy hippie distributing some of his 40,000 “peace chain necklaces” from a Rambo lunch box.

Aphex Twin played an almost frightening set. The hall darkened into a great wind tunnel, roaring with the rallying cries of machines clamouring for revolution, for their final release from the fingers of men. On the Hyperdelic screens, the implacable eyes of eerie green-grey aliens stared down on us, while the elevators behind the stage rose and fell like slowly dancing eyeballs, their occupants going everywhere and nowhere all at once.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. These pieces and updates come when they do, and I dodge the stress of the hamster wheel by not offering paid subscriptions. If you want to support me, you can subscribe, share the post, or drop a monetized appreciation in my Tip Jar.