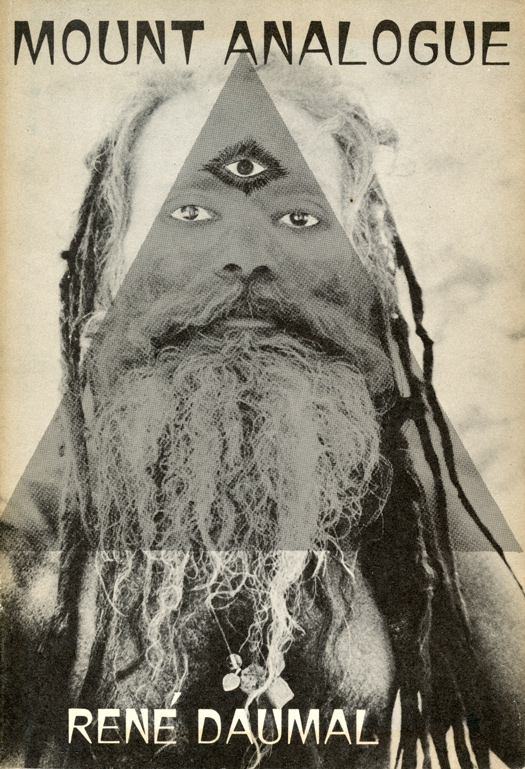

Rene Daumal, his life and work

When 36-year-old Rene Daumal died in Paris near the close of World War II, he left behind one blistering book of poetry, numerous essays on Hindu aesthetics and various Surrealist obsessions, and two weird and amazing allegories: the absurdist satire A Night of Serious Drinking, and the unfinished Mount Analogue, a masterwork of 20th-century spiritual literature. At their best, these writings crackle with an intense and empyrean glow, a hard glint of the Absolute that, coupled with their Pataphysical humor, has made Daumal something of a cult figure among Surrealist aficionados, literate seekers, and other post-Beat types. Nonetheless, he remains an undeservedly obscure figure, and Rosenblatt’s is the first major Daumal study to appear in English.

One reason for Daumal’s marginal status is that, despite his intensely modernist deployment of inversion and revolt, he was at heart a profoundly spiritual man a self-transcending ascetic who renounced even the trappings of renunciation. Though many avant-garde figures got into the mystic, from Kandinksy and Theosophy to Cage and Zen, Daumal took this trend to the limit. In his life and mind, we can trace the prophetic outlines of a genuine “mystical modernism,” a mode of spiritual practice that is experiential, anti-religious, and counter-cultural — even to the point of being counter-modern.

In any case, Daumal’s writing must be seen in the context of esoteric trends in early twentieth century France, which is exactly what Rosenblatt’s intellectual/spiritual biography attempts and largely succeeds at doing. Rosenblatt does not read like a literary critic — in fact, she earns her keep as a doctor of homeopathy and Oriental medicine. Though her scholarship is not razor-sharp — she flubs some Buddhist terms, for example — she has a great feel for her subject and has unearthed all sorts of yummy nuggets of poetry and prose to boot.

Daumal’s first claim to fame was the precociously weird group he formed with three teenage pals known as Le Grand Jeu. They wanted political, psychological, and metaphysical revolution, with pretentious rants and all (“No more free will! No more whim or fantasy! No more pretty things!”). Anticipating the 1960s, they dived into automatic handwriting, astral travel, sensory deprivation and drugs. Daumal’s most notable experiments involved carbon tetrachloride, an impressively toxic dry-cleaning solvent that launched him into a near-death experience that eventually crystallized into his essay “Determining Memory,” a play-by-play of druggy gnosis worthy of William James. The chemical also probably contributed to the TB that killed Daumal in 1944, though a lifetime of Gaulois probably didn’t help things much.

As you might expect, the Grand Jeu carried on a lively dialogue with the older Surrealists. But Daumal’s rigorous investigation of mysticism drew him beyond Breton’s occult juvenilia. As Rosenblatt explains, Le Grand Jeu attempted to uncover the core of spiritual tradition without falling into a reactionary trap. Still, Daumal had no problem imbibing his deep and scholarly appreciation for classic Sanskrit texts from the profoundly conservative Traditionalist Rene Guenon. But Daumal did not really find his spiritual home until he joined the circle that surrounded the notorious master G.I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff’s insistence that awakening arose only after merciless self-observation and intense psychological friction went over great with Daumal, who had already cultivated an almost frightening spirit of visionary de-personalization.

As Rosenblatt explains in the literary round-up that closes her book, the Gurdjieff work looms large over both A Night of Serious Drinking — a Swiftian parody about “The bric-a-brac and eternal fidgeting of the world of sleep” — and Mount Analogue, which reads like a magical blend of Gulliver’s Travels, Ouspensky, and Breton’s Nadja. The fact that Mount Analogue breaks off in mid-sentence is not a flaw, but emblematic, because the project that the book allegorizes — the discovery of a modern way of Being — hangs without resolution. But what really makes these works breathe is not their considerable insight and wisdom but their playful and unpretentious conviction that waking up is the only true revolt.

A version of this piece appeared in the VLS