The author slogs through Britain’s wettest summer in centuries

During my recent water-logged but highly entertaining trip to the UK, where I spoke at the Glade music festival, played psych-rock guitar with Ragnagrok, and biked across London to visit William Blake’s lucky-penny-strewn grave, I decided to spend a few days hiking and camping by myself in Dartmoor, which lies in the southwestern county of Devon. This lonely land of peat-bog and tors— hilltops generally crowned with enchanting piles of granite outcrop, like Pictish building blocks—is about the closest thing to wilderness you get in the UK. Conan Doyle loosed his Baskerville hounds in its environs, whose notoriously confusing and inclement weather only partly explains the thick mist of folklore and rumor that has gathered about the moor over the centuries. Though it is now desolate and almost entirely denuded, the barren 368-square-mile national park is also a millennial palimpsest of human habitation and ritual, and includes scores of hut circles, lonely menhirs, tin mines, path markers, ancient cairns and ruined graves. And wild ponies.

It was my first solo camping trip. I love the outdoors, as much for the relative absence of urban density and infotech as for the subsuming presence of the old organic flows and feints of the analog world, but I never moved past car-camping as a kid. I have always felt a bit cheated about not receiving the patriarchal transmission of backpack know-how, and it has only been in the last few years when, still not getting any younger, I hooked up with friends and started hiking and camping through various mountains of California. Dartmoor seemed bite-sized enough to make a good test run for solo trekking.

It was raining when I caught the bus to Okehampton from dreary Exeter, where I popped into the gloriously vaulted cathedral that morning to visit a Theotokos icon whose blue mantle had, on a previous trip, somehow catapulted me into a cosmic comfortland, but which today reminded me only of the transient contingency of such visions. After buying a map and a cup of salty soup in also dreary Okehampton, I lugged my backpack up the steep lane toward Okehampton Camp, a small military base that lies on the edge of the moorland. Partway up the hill my hip spasmed; for a moment I could not walk. I rested for a few moments, and my leg calmed down, but I embarked with a foreboding reminder of how quickly the world of matter can turn against you. The grey sky was glowering and occasionally moistening my way, but I still half hoped for some sort of clearing.

I had gotten my route from Guy Ogilvy, a Sufi spagyrist who authored the fine little book The Alchemist’s Kitchen and is an old Dartmoor hound. That days’ way was relatively simple: follow the established paths up to Yes Tor, at 2031 feet nearly the highest peak in the area, and then cut across the open moor down into a valley long ago etched by the West Okement River. If I aimed myself right, I would run into a short stand of rare and ancient high-altitude oaks known as Black-a-tor Copse, one of only a few small clutches of woods in Dartmoor and, according to Guy, a mossy and gnarled zone of serious middle-earth magic.

I forded Moor Brook just past Okehampton Camp, a desultory cluster of military barracks and halls, when, ordinance survey in hand, I made my first mistake. I had stolen a quick glimpse of the maps’ legend, but a more steady gaze was required, for I had missed a vital representational code. I don’t know about you, but I would consider it a sign of any exactingly executed topo or road map to mark a crystal-clear difference between a paved and a dirt road. But such was not the case with the OS Explorer Map 28, which represented the course of all roads of a certain width, paved or rutted, with dotted parallel lines. It was an example of one of those subtle but significant English deviations that, like the use of the word quite (which can mean almost the opposite of its American sense), can screw you up.

It certainly screwed me up. For over the next hour, as the mist became a light but steady rain, I marched back and forth across the paved road, attempting to identify which goat track or rutted path corresponded to the dotted parallel lines that led most directly to the tor. I took readings on the wee little compass attached to my Brookstone binoculars, but they made furtive sense and I began to distrust the mechanism. I gave up the quest and renewed it a number of times, vacillating between resignation and effort. Anyone observing me would have thought I was mad, which I guess I was, at least if you count a sometimes debilitating tendency towards indecision as the psychological malady it is. At one point, just as I was crossing a broiling stream, a car pulled over and dropped off a local. He looked at my soggy self, smiled, and said “Great day for camping.” I began to ask a question, but he immediately turned away and marched down a dirt road, as if recognizing that that split second was the one window I had to draw him into my confusion.

Finally I gave up for good and started to walk all the way back, passing the ford on the return trip to Okehampton. But the budding reality of defeat, not to mention the prospect of spending a lonely (and expensive) night in a grim little provincial town, depressed me to no end, which had the positive effect of throwing me back on myself. Fuck it. I was already wet, I am typically good with directions, so I figured I could unpuzzle this sucker and make Black-a-tor.

Standing alongside a fence, marked as a road-like solid single line on the map, I finally discovered my mistake. But as I set out again, I inexplicably continued back along the road I had been criss-crossing for the last few hours, despite the fact that the road was not the one headed toward Yes Tor. I realized this error a half hour later, as I huddled smoking a wet cigarette beneath the stony eaves of some disused barracks on the edge of a farm.

At this point, I had to limit the number of times I checked the map, because every time I yanked the poorly folded, unlaminated thing out of my pocket, its soggy flayed edges flaked away, taking precious bits of data with them. But there was enough information remaining to clarify my latest misstep, which I rectified by sussing out a more Byzantine course through the network of roads that lay east of the Tor. Having finally developed a reasonable trust in the map, I plunged forward with a bit more spunk in my heels, though at this point the inadequacy of my thin raincoat was growing starkly apparent.

After weeks and weeks of unseasonable rain, the ground—juicy in the best of times—was thoroughly soaked. As I trooped gamely past clumps of grass and crumbled granite chunks, I was forced to ford streams that weren’t even on the map. The occasional confectionary sheep, spray-painted with Christmas colors, scurried away as I slogged uphill in the growing rain, which was now accompanied by windy whipping mists that brought visibility down to well less than a hundred yards. My legs were growing weary as I leaned into the driving rain, and I eventually came to the Tor, piled like a Transylvanian castle on the highest peak in the park.

Dartmoor’s notorious weather was now in full effect, and the hour was growing late. I was craving shelter, but though many tors provide caves or crannies for respite, Yes Tor was givin me a big middle finger. I once again considered retreat, but it remained too depressing, and I renewed my goal of getting to Black-a-tor Copse by nightfall. So after squeezing a most modest reprieve from the lee of the tor, I headed south along one of those parallel dotted lines towards the High Willhays, which command Dartmoor’s heights like stacks of misshaped granite pancakes.

I was soaked and tired, having added a number of unplanned miles to my route. But though a glum and anxious air of stupidity and failure nipped at my heels like a shaggy black dog stinking with wet, I was more impassive than bummed. It was 6:30, so I only had a couple more hours of light, although the concept of light was growing increasingly abstract as the mists thickened and my glasses fogged over. According to the map, I did not have very far to go to get to Black-a-tor: maybe a kilometer or so due west down the slope of the hill, which I could not see but assumed lay behind the wall of thick mist.

To make my final stab I would have to leave the world of dotted parallel lines behind and step onto the open moor, which is notoriously disorienting in the fog. But I was up for the challenge, and when I reached the end of the road, I pulled out my handy-dandy compass, only to discover that said compass was not so handy-dandy after all. The crappy little gizmo had become water-logged, and the floating magnet was glued to the edge of its little circular cell, unable, or unwilling, to float free and point north. With shit creek swirling around me, I felt the paddle slip away from my hands.

A sort of bad news deja vu struck, commingling panic and regret and intense irritation, but something more mystic as well: the sure supernatural sense of being the toy of fate. Somewhere just over my shoulder, someone—or something—was definitely snickering. Laugh away spirits! All day long I had forced myself towards my goal not through optimistic enthusiasm but through certain knowledge of the misery of giving up, and so my decision now was actually pretty clear. I stood, took a deep breath, and looked to the west—or what I gathered was west—through the dancing veils of fluttering fog.

A few days before, as we weathered a muddy and rain-soaked electronic music festival called Glade, my friend Naaskow had made the point that, in a few days time, our discomfort would be nothing more than an amusing story. So here was my amusing story, and I wanted it to end with that fucking hobbit grove. I took a final glance at the map, coaxed one brief and apparently solid reading from the compass, shot the abstract vector at some nebulous point on the misty horizon line, and stepped my boots into the grimpen mire.

I walked gingerly between the matted grasses and the steaming bracken and the piles of granite rubble fringed with ferns and heather not yet touched with purple bloom. It was slow going in the rain with a sodden pack, but I started to get the hang of things as I plunged west, following the decline. Suddenly, I wooshed into one of those dreamy, slow-mo slipstreams of consciousness caused by abrupt and unexpected physical fuck-ups. The carpet of mossy lichens where I had just placed my foot proved not to cloak a thick wad of spongy peat, but rather a pool of rainspew and rot. In other words, I fell into a bog.

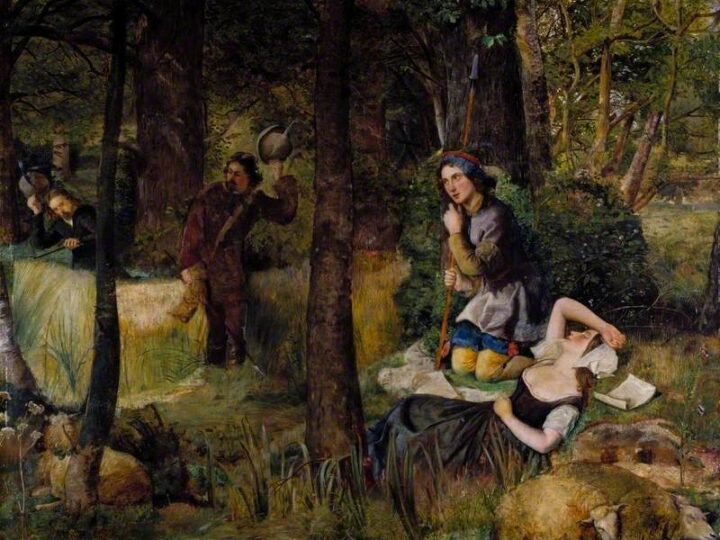

And there I was, with Sherlock and the good doctor, on the trail of those dastardly hounds: Rank reeds and lush, slimy water-plants sent an odour of decay and a heavy miasmatic vapour into our faces, while a false step plunged us more thigh-deep into the dark, quivering mire, which shook for yards in soft undulations around our feet. Its tenacious grip plucked at our heels as we walked, and when we sank into it it was as if some malignant hand was tugging us down into those obscene depths, so grim and purposeful was the clutch in which it held us.

I yanked myself away from that malignant and stinky hand and continued on, unharmed but shocked, my boots soaked with a fetid slime whose funk still has not quit them. Things had definitely gone south, but I continued west, or what I hoped was west. A few more football fields later, and I glimpsed a blackened twisted tree limb. I was on the upper edge of the copse, which clung to the northwest slope of the valley atop granite rubble that lent the place the air of an antediluvian wizard ruin.

I took great care with the slippery final descent into the gnarled and lichen-cloaked arms of the wood. Needing respite and shelter, I worked like a robot, found a flat spot along the path that followed the river, pitched the tent, dried myself, made some food, and rolled a spliff. It was the most restful evening I have ever spent in a tent.

I did not know that the following day would be as blissful as it turned out to be—amidst a relentless march of colossal cumulus clouds from the west, an intermittent sun would dry out me and most of my stuff, and shed its beams on a long hike and a parade of campsite amusements: a wild but docile herd of shaggy-assed ponies; a shepherd and his son driving their flock along the path; a crew of determined young hikers, five unfriendly guys and a friendly woman, fording the river and clambering toward Corn Ridge. Not yet knowing this, sopped and huddled alone in my tent, with rain unrelenting, I still felt the awakened calm of sustained contentment. Though my luck was poor and my execution shoddy, dogged persistence had won the day. A for effort, as they say.