Kung Fu: The Legend Continues

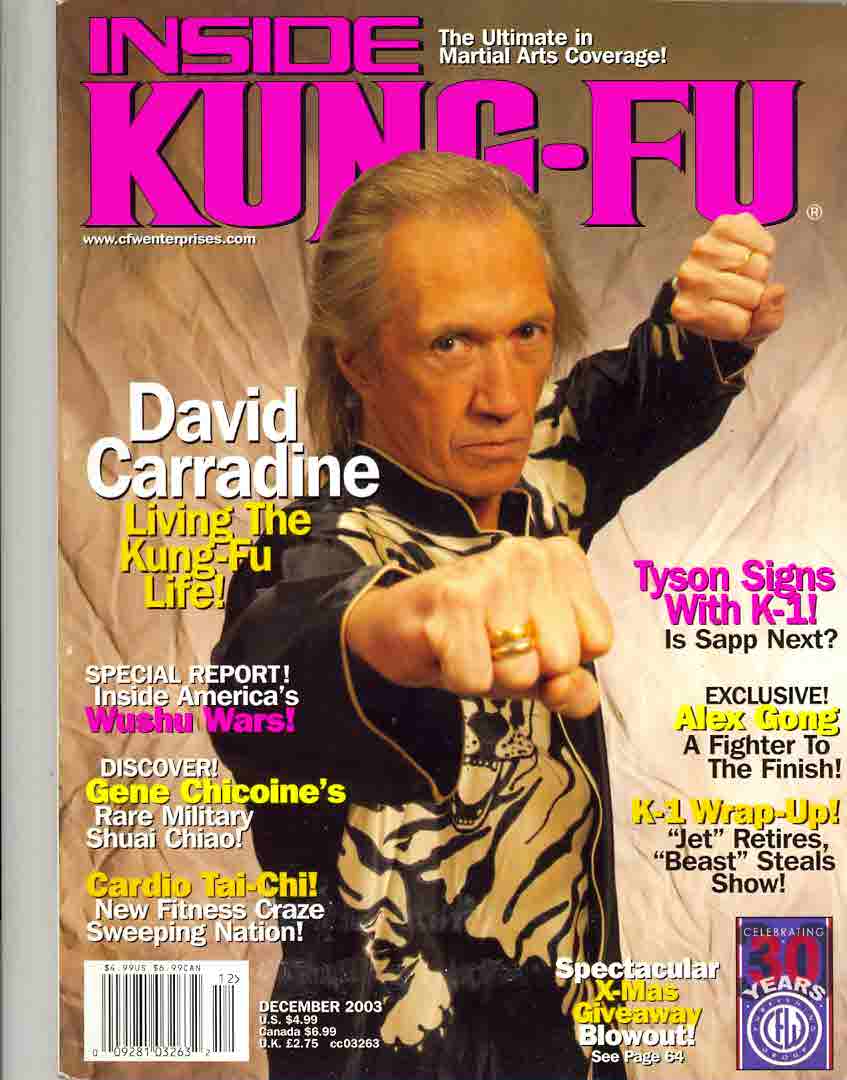

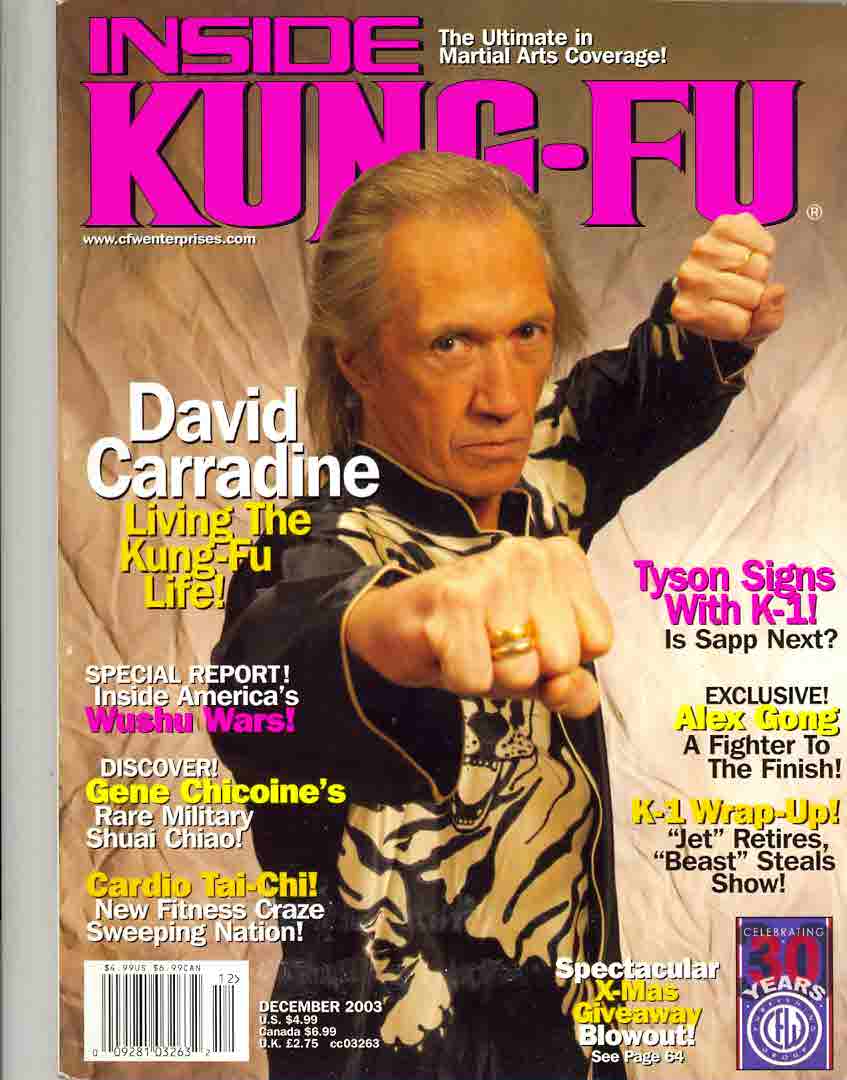

Forget about the Mod Squad — the only field-day the hippies got on TV was Kung Fu. Not only was Kwai Chang Caine a dangerous Shaolin freak with bare feet, mystical powers, and a Billy Jack hat, but he was played by David Carradine, a dangerous Hollywood freak with Aquarian babes, prodigious appetites, and a hut in the Hollywood hills. Kung Fu‘s vibe was scruffy and occult, and its formal effects memorable — all those flashbacks, slo-mo kicks, and overexposed shots of sunlight demonstrated that longhairs saw things differently because they saw things differently. As much a part of early ’70s culture as blaxploitation films or really, really wide bell-bottoms, Kung Fu was as simultaneously silly and noble as the counterculture itself.

More importantly, Kung Fu interjected its transmuted hippie code into TV’s most sacred and conservative space: the western. While it essentially capped the western’s domination of TV dramas (Gunsmoke and Kung Fu were both canceled in ’75) and portrayed many stock western characters as racist and arrogant thugs, the show praised the genre as much as burying it. Caine refigured the cowboy’s solitude, reticence, and spiritual homelessness into a nomadic wisdom, while his special-effects feet punctuated the fact that the violence of the western approaches, at its allegorical extreme, total hallucination.

After years of I Ching addiction and T’ai Chi dabbling, I can still trace everything I love about the Tao to the pearls blind Master Po dropped on the puzzled Grasshopper in those priceless flashbacks to Caine’s Shaolin temple. But the Tao that Kung Fu emulated was not Lao Tzu’s Way but the American Way, a flux of hobos and beatniks, of Captain Ahab and Clint Eastwood and Kesey’s merry pranksters. What unites all these wandering figures is violence: violence against the self, against convention, against other bodies. Caine’s reason for fleeing China for America — his impulsive murder of a member of royalty — made him American. And in the early ’70s, he briefly unified the counterculture’s split desires, both their cultic quest for inner peace and their lingering urge to put a foot up the Man’s ass.

Kung Fu‘s “contradiction” between meditation and bone-crunching melees – besides already existing to some degree in the martial arts themselves – served up a freak form of an old American dream: violence at once spiritual and righteous. Caine fights without rancor or sweat, not producing violence as much as reflecting it back to its source. And since he’s in America, the flow is endless.

Playing Kwai Chang Caine’s grandson in the new Kung Fu: The Legend Continues, a grizzled, gravely David Carradine says “I am to my ancestor as shadow is to form. I am not yet whole.” This statement is correct. Kung Fu: The Legend Continues is fragmentary and thin on substance, a weird but appealing blend of B-movie shtick, magic, self-mockery and cop show gloss. Spirituality floats through the show like incense in a strip joint, and the fights are sonic as well as visual treats, as bone-crunching kicks alternately recollect John Wu, peanut brittle, and autumn leaves. And Caine still has that taste for ponderous gnomic utterances — when someone asks if he has a destination, he responds with “a destiny, yes, not necessarily a destination.” But from the pilot’s opening shot — Caine walks out of the old show’s trademark sunset shot onto a freeway — to the jokes about Caine’s Shaolin sound-bites — “Where’d you get that? Out of a fortune cookie?” says one gangster — the show laughs at its own mystical shit, thereby letting the scent linger longer than normally possible on TV.

As told in the fun two-hour pilot, Caine is a contemporary Shaolin master whose temple in Northern California was destroyed by a renegade priest. Hearing that his son died in the blaze, Caine hits the road for years until he winds up in LA’s Chinatown, where he gets embroiled in a conflict between the community and a local extortionist. As the violence escalates, Caine encounters his son Peter, now a cynical cop, whose youthful spiritual ideals have been crushed by the ’80s. After dispatching the baddies, the duo seem ready to team up for future crime-fighting.

Like The Incredible Hulk, Highway to Heaven and The Fugitive, the original Kung Fu used a wandering loner to stage a nomadic ethics that lies outside of conventional authority. But today Caine needs to be tied down, to the city, to one place. By staying put in Chinatown, Kung Fu does hold out the possibility of exploring some of the dynamic of a Chinese ethnic enclave, which would make up in some small way for the fact that David Carradine is no more Asian today than he was twenty years ago.

But the real tie-down here is not to a lease, but to the law. Just as the cool anarchy of Clint Eastwood’s man-with-no-name devolved into the disturbing vigilantism of Dirty Harry, the new Kung Fu tentatively aligns the urban Shaolin with the men in blue. The new series’ use of flashbacks — returning not only to the California temple but to the flashbacks of the original series — makes it clear that The Legend Continues wants to grab what some garbled idealism from the freak era and graft it onto the cynical gloss of post-Miami Vice cop formulas — nauseating formulas which embody our alienation from both crime and authority. The irony of all this is not lost on Carradine — one cannot peer into his eyes without recognizing an essentially lawless man.

In returning to TV from years in the action-adventure trenches, Carradine seems to have dragged some of that straight-to-video flare with him. Ranging from high-tech weapons to copious female flesh to gaudy violence, the show does not even attempt any of the solid dramatic “relevance” that could make the original so painful. So far the bad guys are particularly bubblegum — the first episode’s nasty is some Caucasian in black robes who was trained heretical temple of psychic assassins, while the pilot’s villain is a Shaolin seduced by the dark side of the force, who screams things like: “The source of all life is a profound mystery! It is the void of substance and form! It has lived since the dawn of existence!”

But rather than just settling into a cheesy exploitation rut, The Legend Continues‘s comic-book density actually highlights the apothecary’s Chinese lore and Caine’s mystical chops, “spiritual” imagery that would fall flat in a more middlebrow vehicle. This tension may make the series a fresh promulgator of the cult of enlightened trash, a Corman cult where David Carradine has long been high (low?) priest of the gutter mysteries. Banished from the Hollywood mainstream, Carradine remains one of his generation’s great character actors, not because he’s such a great actor but because he’s such a character. From Mean Streets to Wizard of the Lost Kingdom II, from fast cars and booze to T’ai Chi instruction videos, Carradine takes the freak edge of folks like Bruce Dern and Dennis Hopper into the realm of sorcery. Not only do his crinkly eyes and cryptic expressions make him look weird (one of the pilot’s better jokes is Peter’s description of his father’s racial looks as “enigmatic”), but his undeniable physical presence embodies a stillness at once wise and perverse.

Rumor has it Carradine even has Kung Fu symbols tattooed on his scrotum, a fitting symbol for a man fated to be known more for great schlock like Death Race 2000 than for great films like Bound for Glory. Watching this nearly 60-year-old figure settling comfortably into the flute-playing, kidney-punching frame of Kwai Chang Caine, you sense he doesn’t really care than much, because he’s beyond it all.