Listening to the Jesus Music of the Seventies

I don’t believe there is a common thread running through the myriad of musics that have composed my listening life. But if there were, it would have to be a love of and fascination with the sacred, a capacious aesthetic category that, for me, includes both explicitly religious music and those exotic, popular, or avant-garde forms that variously juxtapose, fuse, and transmute the ever shifting boundary between the transcendent and the profane.

Beneath this immense canopy, Messiaen butts heads with Brian Wilson, Pentagram with Pandit Pran Nath, Bach with Sun City Girls. Many genres and traditions have found a home as well: dhrupad, raw gospel, black metal, Bollywood bhajans, soul, psy-trance, roots reggae, ethnographic recordings, modern minimalism, cosmic jazz, qawwali, new age, ars nova, Five-Percenter hiphop, freak folk, the ritual beats of the African diaspora, and all manner of psychedelic and dub infections. Besides providing me with an interesting angle on music writing, sacred listening has also created an arena where my own circuitous loops of spiritual seeking and naturalist doubt might be nourished and indulged, mocked and intensified.

But the zone of sacred music that has compelled me the most as religious music – in other words, where my enjoyment and obsession is wrapped up most intimately with my critical fascination with faith and testament, ecstasy and prophetic rage – is, hands down, the independent and small press Jesus music of the late 1960s and 70s.

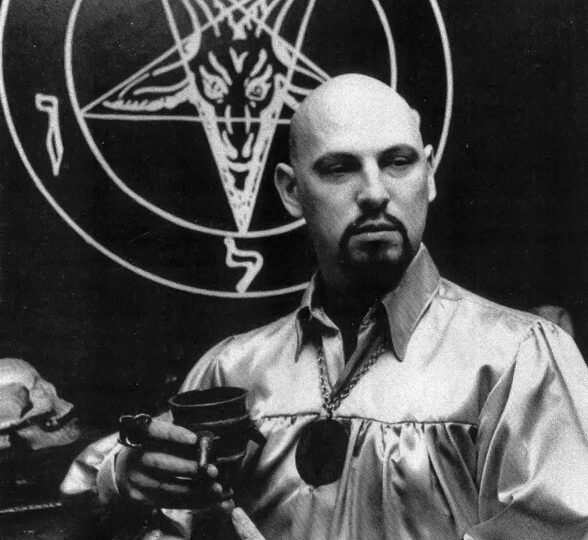

For a historian of religious subcultures, this music holds an obvious appeal. But Jesus music also radiates a special aura for me because it allows me to sneak up on one of the most curious and enigmatic periods of my own spiritual life: the six months or so I spent in 1983 as a born again Christian. It’s a long story, as you might imagine, but let’s just say that by the time I entered junior year at Torrey Pines High School – an open-air 70s campus north of San Diego whose most famous alum is the skateboarder Tony Hawk – I was swirling in a deep, dark weirdness. LSD, Thai stick, and occult literature had opened the doorway to strange, obsessive headspaces fueled by unrequited desire and trance practices snatched from the wreckage of coastal Southern California’s spiritual counterculture. A comparative literature class found me reading Baudelaire, Sartre, and a number of books starring the Devil, including Mann’s Dr. Faustus and Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. After Christmas, Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation Of Christ led me into an esoteric experience of the Christian imagination, one in which a loving godman was capable of vanquishing the Lovecraftian evil I sensed afoot.

Early that spring, I met a couple of Christian surfers in typing class, dudes with metalhead bangs who invited me to a bible study group held in someone’s living room. There I met a charismatic young evangelist with surfer locks and an impressive command of scripture. The intoxicating incense of the Word and the groovy agape of this informal but devoted community kept me enchanted despite my antipathy towards larger church gatherings. But come summer, the growing contradictions of the claims – not to mention my desire to have sex, smoke pot, and enjoy Peter Gabriel without worrying about the supposedly Satanic imagery in his videos – led me to backslide comfortably into Deadhead heathenism.

That said, my imagination remains marked by my teenage turn to Christ, like the tattoo of an old love I can’t or won’t remove. And I continue to warm to this sweet and enigmatic flame in Byzantine icons, Gnostic scriptures, church architecture and the far-out sounds of the Jesus freaks.

Though I did not know it at the time, the soul surfer wave I caught in the early 1980s had started more than 15 years earlier with the emergence of the first Jesus people in California. Lots of acid heads had Jesus trips, especially in the late 1960s, but some concretized their visions through a radically new model of born-again faith that offered “one way” out of the hedonic and metaphysical chaos of the times. Scores of young people gathered in Christian communes (and in the occasional cult, like the deeply creepy Children of God), opened Christian coffee shops, and became street preachers alongside a few older media-savvy ministers like Arthur Blessitt, who walked Sunset Strip with an enormous cross. While these scruffy converts rejected the sexual and pharmacological mores of the hippies, they also epitomized the countercultural dream of personal and social transformation through ecstatic and collective spiritual experience.

Initially, Jesus people had little interest in America’s mainstream Christian culture or its old school fundamentalist fringe. Instead, these hirsute acolytes established their own cultural networks through already existing forms of countercultural media and expression: underground newspapers, posters, buttons, comics, earthy clothes, long hair, and, most importantly here, vinyl records and the drums, mics, and guitars (wah-wahed, country-fried, and soft as a folky dove) that filled those grooves. While a few early Christian rockers, like Larry Norman, Barry McGuire, and Glass Harp’s Phil Keaggy, had commercial chops from the get-go, the vast majority of Jesus music was released through small independent labels and private press LPs. Indeed, the earnest but amateur foibles of this music reflected, in media terms, the unmediated “personal relationship” with Jesus so central to the freak faith. No church standing between you and God, and no fancy engineer or A&R guy either.

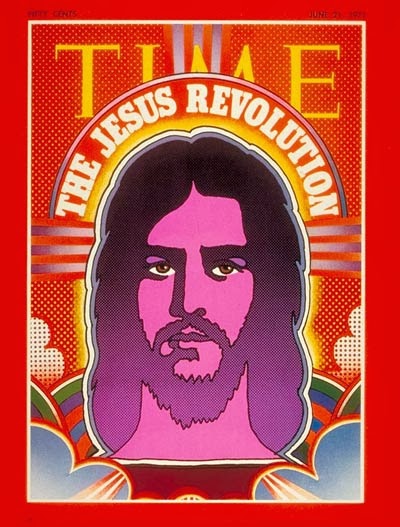

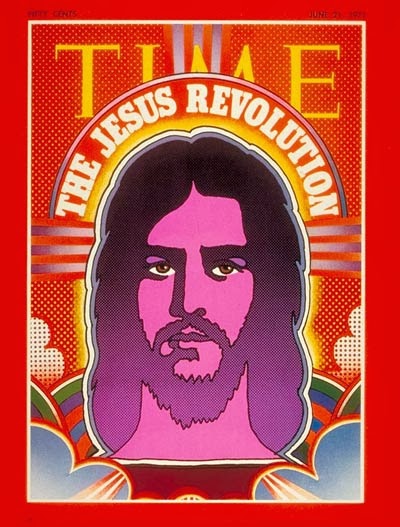

Following the summer of 1971, when Time put The Jesus Revolution on the cover, the movement became gradually incorporated into more conservative ideologies and Church structures – institutions that would in turn grow less traditional, more blue-jeaned and Hawaiian-shirted. This trend, which emphasized the intimate experience of Jesus, directly shaped the informal vibe of many modern megachurches and spawned a number of enormously popular revivals (including the Vineyard scene that enticed Bob Dylan). This process of assimilation was mirrored almost exactly by the transformation of Jesus music – scruffy, eccentric, largely amateur and occasionally ferocious – into the slick commercial genre of contemporary Christian music (CCM). Emerging from a network of labels like Sparrow, Maranatha!, and Myrrh, CCM became a thriving market space that would launch 80s crossover stars like Amy Grant and the hair metal band Stryper. Veteran archivist Ken Scott, whose invaluable collector’s guide runs to almost 200 pages of small print, pegs the end of the Jesus music era at 1980, but I generally stick to the 60s and early-to-mid 70s.

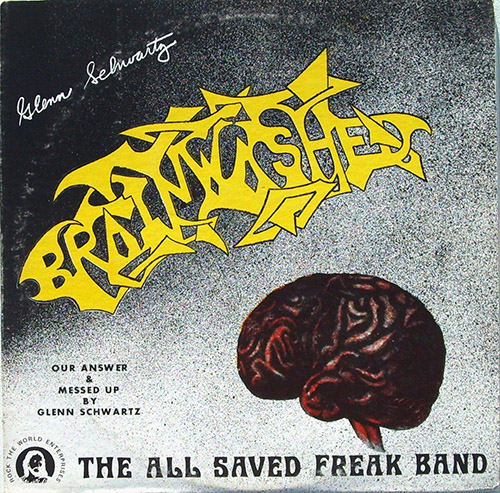

As Scott’s well annotated want list suggests, Jesus music has long been a desideratum for vinyl collectors, both Christian and not. In a way, it’s a perfect market for such obsessives – a category in which I must now place myself, having recently dropped a Benjamin on a single, scuffed-up LP (The All Saved Freak Band’s memorably entitled For Christians, Elves, And Lovers). Because there are so few copies of so many obscure Jesus music recordings, collectors have had a field day discovering, hoarding, and trading these often creaky marvels. But because most people are uninterested in the music (and hate it if they hear it), even amateur crate-diggers can still discover the occasional charmer.

Probably the first heathen listeners to cotton on to Jesus music were the psych collectors, who recognized that some Jesus music was not only heavily distorted but kicked much lysergic ass. Fred Caban, the guitarist for the trail-blazing Orange County power trio Agape, left swirling Hendrix fingerprints across his fretboard on the band’s Agape (1971) and Victims Of Tradition (1969). In the Northwest, Wilson McKinley matched Haight street boogies to CSNY vocals (and terrible production values), while the Sacramento act Azitis wove haunting keyboards, fuzz guitars, and Moody Blues delicacies into their end-times masterpiece Help (1971). The riffs and vocals of The Exkursions are as crude and Cream-y as anything on the Nuggets garage rock comps, while the working class Angelenos in Fraction produced the heaviest Christian psych album of all in Moonblood (1971), a stoner rock apocalypse driven by Jim Beach’s nearly deranged Jim Morrison baritone.

But it goes beyond distorted riffs. Part of the power of this stuff derives from the prophetic intensity of these young freaks, who, clutching their paperback copies of Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth, transformed Summer of Love millennialism into an urgent Last Days blaze. This spirit also anticipates the sort of punk refusal that later informed straight edge, as the countercultural rejection of the fallen straight world looped around to mock sloppy countercultural values as well. The singer-songwriter Larry Norman, one of the early pillars of Jesus rock, was a Dylanesque master of such witty digs at his own partying peers.

Such militancy reached its peak (or nadir) in the aforementioned All-Saved Freak Band, a sprawling Ohio group that crystallized around an incendiary renegade preacher named Larry Hill. Their cult-like communal farm also attracted the early James Gang guitarist Glenn Schwarz, who supercharged The Freak Band’s blues and psych rock, balanced in turn by some charming chamber folk. After Schwarz was briefly kidnapped by his family and subjected to cult deprogramming techniques, the band entitled their next record Brainwashed (1976).

The prophetic conviction that enflamed so many Jesus musicians – as well as their pushy desire to convert you as you listen to the record – provides an uncompromising (straight) edge to this music that sharpens its sometimes shambolic execution. But such damning convictions are often balanced with a mystic sweetness, a kind of sunlit hippie sentiment, and even sentimentality, that is paradoxically saved – at least some of the time – through the very sincerity of its yearning. Postmodernism taught us to distrust authenticity in rock music (and everything else), but sincerity makes a more modest claim than authenticity. Sincerely held convictions seem to lend a more vibrant extra-musical substance to musical expression – especially the sort of singer-songwriter folk-rock that so many Jesus people performed. In fact, I now find myself vibing with drippy folk and soft rock ballads – particularly those by Malcolm & Alwyn, Harvest Flight, Kevin & Clare, and The 2nd Chapter Of Acts – that would bore me to tears in a secular context, simply because the sentiments are enlivened with a palpable if puzzling belief.

Of course, to enjoy the fruits of such intimate sincerity while more or less rejecting its object can sometimes feel a bit perverse. Though I actively enjoy discovering and exploring this music, and maintain my own curious relationship with the Superstar, I fear sometimes that I have fallen into the sort of irony that allows the more arch hipsters among us to passionately declare their love for unintentionally bad or incredibly strange recordings. But the form of the song is capacious enough to briefly house all our contradictions and resistances. Songs can be testaments or jeremiads, and therefore participate in the troubling extramusical work of religion. But they are also, and always, sonic fictions. Poems of longing. We allow ourselves all manner of emotional affirmations and imaginative transports within the bookends of our listening, including, in my case, some mediated hang time with the groovy freaky Jesus of my teenage dreams.