Renaissance Magic and Science

It’s a rare treat to be able to trace an abiding intellectual obsession to a single moment in time. But so it is when I ponder my ongoing fascination with the occult fringes of science, and, more generally, with the anthropology of knowledge. It was senior year in high school, and for once I was paying attention to Mr. Grey, a physics teacher whose name I don’t actually remember but whose entire being radiated the sort of officious banality my typically romantic and alienated teen self loathed. A retired Navy guy (this was San Diego) with a gravely voice and a grey buzzcut, Mr. Grey was a droning, pedantic bore, and it is no wonder that I spent most of the classes in the back row, cracking jokes with Chuckles and playing hot’n’heavy footsie with the impish Jenny Cole. I liked physics, but I ignored the class.

This was not the case, however, on the day we dug into Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion. Reading about Kepler’s discovery of elliptical orbits in the textbook had fascinated me, not so much because I love astronomy (which I do), but because the textbook had had the rare generosity of mentioning that, while Kepler thought that the three laws were pretty nifty, what really rocked his boat was his discovery that the relationship between the planetary orbits could be neatly mapped onto a nested organization of the five Platonic solids, wherein the vertices of one solid touched the faces of the next largest solid in the series. In other words, Kepler thought that what we now consider his immortal astronomical discoveries were less significant than his metaphysical — and essentially occult — speculations about the geometrically perfect harmony of the spheres.

This visionary dimension seemed deeply important, so I asked Mr. Grey whether Kepler’s wacky Platonic Russian doll should have any bearing on our understanding of Kepler’s achievement. He didn’t even understand the question, and we blubbered back and forth for a bit until I gave up and resumed the footsie action. To Mr. Grey, all that mattered was the usefulness of the laws; all the rest was trash.

To me, the speculative context made all the difference, because it showed the vital and organic correspondences between what we think of as science and what we think of as occult or theologically-informed cosmology. More to the point, it told us something vital about Kepler himself. Years later, when I read Arthur Koestler’s great book The Watershed, I felt confirmed in my view that this historical conjunction is not just of historical interest, but strikes at the heart of the meaning and function of cosmology, certainly in the Renaissance, and possibly–probably–today. More deeply, it points to the role that the poetic imagination–the fancy that weaves analogies and correspondences–plays in the construction of our “real world.”

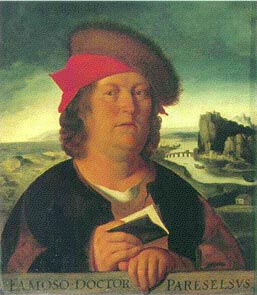

All this was brought back to me recently when I was in London. I was scanning the ever-excellent and ever-expanding book collection of my pal the Pilkdown Man. Topping one of the towers of text was The Devil’s Doctor, a book about Paracelsus and “the World of Renaissance Magic and Science” by the British science writer Philip Ball. It was a fortuitous discovery, because, as part of an ongoing but essentially lazy quest to wrap my psyche around alchemy, I had recently been drawn towards Paracelsus: the wonder-working itinerant sixteenth-century healer who is sometimes cast as the Copernicus of medicine. Rejecting the leech-loving, bass-ackwards, and literally by-the-book healing practices of most medieval doctors, Paracelsus instead made room for a medicine based on plants, material causality, and self-healing powers of the body.

Having already brushed up against Paracelsus’ own rich but impenetrable prose, I was immensely relieved that Ball had appeared to lead me through the Renaissance thickets by the secondary hand. (I told you I was lazy.) Given the noodle-limp dollar, The Devil’s Doctor was about the only thing I purchased in the UK. I read almost the whole thing on the plane ride home, in between marveling at the glittering, melting majesty of Iceland and Greenland as they unrolled below me and marveling at the complete absorption of all but one of my fellow travelers in the movies flickering across their cramped little screens.

Ball’s book is a marvel of the middle of the roadclear and readable, entertaining and informative, and quietly significant. With sympathy and a tart wit, Ball tells Paracelsus’ fascinating story, which is rich enough for a crusty biopic starring Harvey Keitel. Ball also puts this very strange man in context by painting a number of relevant historical backdrops: medieval medicine, the proto-sciences of mining and metallurgy, Renaissance astrology, the early Reformation, the legend of Faust.

These micro-histories alone are worth the price of admission, but what truly delights is Ball’s portrait of Philip Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim, aka Paracelsus, a cranky, brilliant and, yes, bombastic vagabond healer. Paracelsus was seemingly in love with skewering sacred cows and pissing off the local muckety-mucks — especially those doctors who siphoned their high-status positions from the muck of ignorance and credulity. Medieval doctors didn’t even carry out the gruesome surgeries of the day, which were left to lower-class barbers while the “scholars” flipped through Galen and plucked out recommendations. Paracelsus hated these guys.

So he had to keep on trucking. At a time when few folks traveled far from their birthplaces, Paracelsus wandered everywhere — the Holy Land, Egypt, western Europe, England, Sweden, Russia, Turkey. He picked up tips from Tartar shamans, drank and ranted in bars, mocked those in power, and healed a lot of people. My favorite tale took place in Basle, during one of Paracelsus’ controversial and, as usual, short-lived teaching gigs. In a lecture hall filled with doctors, Paracelsus claimed he was about to reveal the greatest secret of medicine — and then unveiled a steaming plate of human shit.

The crap was more than a prank. As Ball explains, it also derived from Paracelsus’ alchemical belief in the potential fecundity of waste and decay. Indeed, one of Paracelsus’ many remarkable (and often kooky) innovations was to apply the basic dynamics of alchemical transmutation to the intertwined world of plant medicines and the human body. Ball calls it “alchemical materialism,” a sort of enchanted bio-chemistry. Even the concept of metabolism arose from Paracelsus’ dynamic and, in many ways, highly corporeal understanding of bodily beinga corporeal understanding that looked to herbs and minerals but was by no means adverse to the invocation of astrological forces or the healing power of mumiaaka, powdered mummy.

It’s to Ball’s enormous credit that, while remaining firmly rooted in western science, he understands and appreciates the premodern, theological (and magical) aspects of Paracelsus’ worldview. The Renaissance is almost defined by this extraordinary conflict between the premodern imagination and a budding skeptical modernityin fact, it is precisely Paracelsian-style “natural magic,” with its pragmatic, operative character, that bridges the gap between dusty Aristotelian book lore and empirical science. Ball defines Paracelsus himself as a “skeptical mystic”deeply beholden to alchemical cosmology, but also critical of the existing social order and its medical shibboleths. It is because of this perspectivein betwixt and in-betweenthat Paracelsus was able alter and reimagine the west’s fundamental culture of healing.

And of poisoning. One of Paracelsus’ great insights, which sometimes earns him accolades (or blame) as the grandfather of homeopathy, was that “poison” is a relative term, if not a hidden balm. Mercury, for example, whose toxicity was known, could cure syphilis, but only in moderation. “Is not a mystery of nature concealed in every poison? What has God created that He did not bless with some great gift for the benefit of man? Why then should poison be rejected and despised, if we consider not the poison but its curative virtue?”

There is something searching and empirical about this insight. At the same time, it also reflects the deeply dialectical nature of alchemy, which finds in antinomies echoes of the fundamental dynamics of the soul. In the end, Ball is enchanted by these dynamics while recognizing that they are, from a scientific view, wrong-headed. I remain tremendously enamored of what Ball calls “chemical theology”, but I also understand why Ball insists on the errors of the approach. When I caught pneumonia last spring, I was gobbling down penicillin, not wielding a dowsing rod or measuring the heavens.

Ball praises Paracelsus for rejecting the hide-bound medicine of the medieval docs, but you can tell that the biographer also recognizes what we moderns lose when we leave the magical correspondences of the religious imagination behind. In the end, this loss of “soul” just might wind up sickening our bodies as wellto say nothing of the planet. “In all things there is a poison,” wrote Paracelsus. “It depends only upon the dose whether a poison is a poison or not.”

The superstitious and sometimes harmful credulity of religious tradition can certainly be considered a poison. But for many of us moderns, hurtling towards a chilly posthumanism, a draught of the poetic and cosmic imagination that feeds religious credulity can wipe away the pain. And even, potentially, heal it. For though skepticism and empirical reason have cleared away many cobwebs of theological error, we are all swimming in the toxic sludge these cultural solvents have left in their wake. The alchemist can envision the gold growing in the sludge; the realist only marvels at the mess we’ve made, and turns up the collar of his coat.

, a book about Paracelsus and “the World of Renaissance Magic and Science” by the British science writer Philip Ball. It was a fortuitous discovery, because, as part of an ongoing but essentially lazy quest to wrap my psyche around alchemy, I had recently been drawn towards Paracelsus: the wonder-working itinerant sixteenth-century healer who is sometimes cast as the Copernicus of medicine. Rejecting the leech-loving, bass-ackwards, and literally by-the-book healing practices of most medieval doctors, Paracelsus instead made room for a medicine based on plants, material causality, and self-healing powers of the body.

, a book about Paracelsus and “the World of Renaissance Magic and Science” by the British science writer Philip Ball. It was a fortuitous discovery, because, as part of an ongoing but essentially lazy quest to wrap my psyche around alchemy, I had recently been drawn towards Paracelsus: the wonder-working itinerant sixteenth-century healer who is sometimes cast as the Copernicus of medicine. Rejecting the leech-loving, bass-ackwards, and literally by-the-book healing practices of most medieval doctors, Paracelsus instead made room for a medicine based on plants, material causality, and self-healing powers of the body.