The Technofreak Legacy of Golden Goa

On October 26 2023, the psy-trance DJ Goa Gil passed from this earth. I got to meet Gil three decades ago, when I was writing a piece that, while it was an extraordinary blessing to research (especially on someone else’s dime), proved a mighty pain in the ass to get into print. I first heard about the psychedelic rave scene in the Indian state of Goa from the guys in the techno act Orbital, who were very nice blokes. In those days I had a contract with Details magazine and convinced the editor-in-chief, a smart fellow named John Leland, to send me there for a feature. By the time I returned to the States and wrote up the piece, Leland was gone. Over the next few months, the new guy, who I dubbed Mr. Hollywood, demanded an ungodly number of rewrites and then killed the piece anyway.

A version of the thing wound up running in Option in 1995, under the name “Sampling Paradise.” By then the prose had been kinda beat down by all the processing, and many meatier topics left untouched. I later reworked the article into a more scholarly (specifically Deleuzian) article that appeared as “Hedonic Tantra” in an academic collection on rave and religion edited by my good friend Graham St. John. What follows is the “Sampling Paradise” article, which also contains a rare interview with Laurent, one of the originators of the Goan sound.

Gil was happy to get himself out there, and since my interview, his story has been told many times (“Goa Gil: The Unbelievable Story of Trance Music’s Spiritual Father” in Trax Magazine (now defunct) was particularly fine, and contained many rare and wonderful photos). I never hung out with Gil again. Though I have tried to catch the psy-trance vibe many times, and had some genuine ecstatic experiences, I remain lukewarm on the genre (more or less evolved from Goa trance) so tended to skip parties were Gil played. But I admired him from afar. As a DJ, Gil never wavered from his commitment to a particularly heavy, hardcore, and dark subcurrent of psy-trance. It would have been very easy for him to relax into a happy hippie vibe but instead he kept the brutal cosmic ferocity high. No doubt many brains were scrambled along the way, but I trust that Gil kept some cosmic love in the mix.

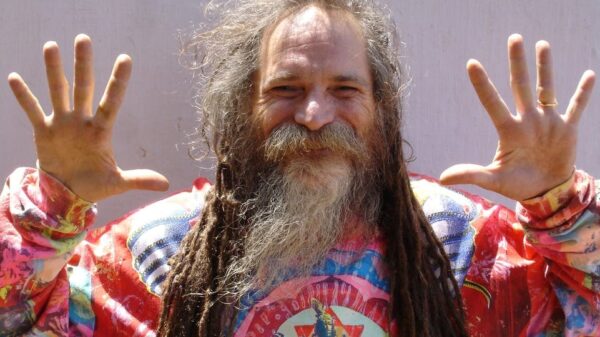

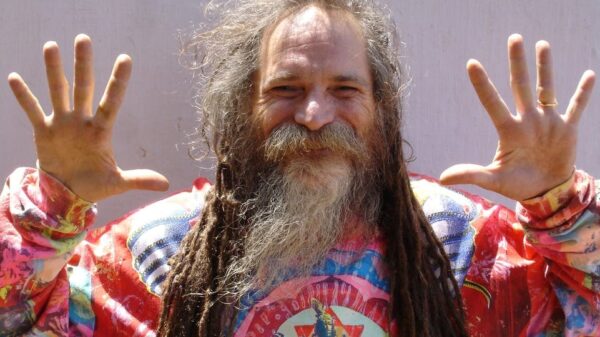

Goa Gil, 1951-2023

It’s one hour past midnight, and the jungle throbs with techno. The tropical breeze off the Arabian Sea is warm and wet. I stuff a wad of rupees into the outstretched palm of the auto-rickshaw taxi-driver, and head toward the noise. I’m 350 kilometers south of Bombay, in India’s coastal state of Goa, and I’m about to hit a rave.

The forest clearing swarms with bohemian backpackers and European hipsters strutting their cyberdelic stuff: holographic sneakers, flared fractal jeans, floppy Dr. Seuss hats stitched with the mirrored cloth of Rajasthan. The freaks gyrate around junky speaker stacks, soaking up the interstellar trance beats like they earlier soaked up the sun. A lithe Japanese girl dances by with a glowing plastic jewel affixed to her third eye, giving me and everyone else she encounters an omnivorous grin. An old Indian beggar passes through the crowd, the black lights turning his turban the color of moonlit bone.

The DJ booth lies at the edge of the clearing, set beneath low-hanging trees and cordoned off with bamboo. A large middle-aged hippie with white-boy dreads and a bearded, sun-burnt face stands behind the mixing table, pushing buttons and slapping DATs into two small decks wired through a pint-size mixer powered by a generator hidden in the bushes behind. Alongside stacks of black-matte cassettes stands a candle, a smoldering stick of incense, and a small devotional portrait of the Hindu yogi Shiva Shankar, sitting in the half-lotus position on a tiger skin.

“That’s Gil,” says one of the Indian locals mobbing the techno-shrine. “He’s one of the best.”

I had already heard about Gil from Genesis P. Orridge, who had filled me in earlier on the technofreak legacy of late-60s London clubs like Middle Earth and UFO. “The basic premise was smoke and light shows, large quantities of ecstatic chemicals, and dancing like a dervish to accentuate your artificially-induced mental state to a point that was equal to and integrated with an ecstatic religious state.” When the scene decayed, the heaviest psychedelic warriors split, taking their musical alchemy with them. Some went to the Spanish island of Ibiza, while the more esoteric heads went east. Though Gil was from San Francisco, he had trod a similar path. “You have to find him”, Genesis told me. “He’s one of the links.”

But Gil is too lost in his craft to talk, and I merge back into pulsing psychedelic bardo of the dancefloor. I’ve never seen people move like this: at the edge of their bodies, ceaselessly flowing, like Deadheads bonedancing in overdrive. Disembodied vocal samples float through the air like ghosts, triggering mindfucks left and right: “There are doors.” “The last generation.” “Everybody online?”

Craving touch-down, I head for Goa’s gypsy version of a chill-out room. In an adjacent field, local village women have laid out rows of straw mats and piled them high with fruit and cigarettes and bubbling pots of chai (tea). Scores of freaks flop out on the mats, smoking copiously by the light of kerosene lamps and sipping syrupy brew from scalding glasses.

I plop down next to a crowd of Brits. Pete is in pajama pants and an open vest, his aristocratic Tory features oddly framed by long scraggly hair. Hunched next to him is Steve, a skinny blond twentysomething rolling a spliff.

“Have you seen The Time Machine?” Steve asks me. “There’s this noise that the Morlocks use to call the Eloi underground. That’s exactly how it was five years ago when my friends and I first came to Goa. We heard this booming rhythm in the distance. We didn’t know where the fuck we were, but we just crashed through the jungle with our torches. The sound was calling us. I got real paranoid that there was some alien intelligence directing the computers, like the Morlocks, summoning us to a place where they were gonna eat our souls.”

Pete nods as if nothing his friend says could surprise him. “My first party, I just got the feeling I was in some spiritual Jane Fonda gymnasium,” he says. “Boom, boom, boom, and everyone going into trance. It was quite alienating actually.”

“I just get a feeling of conspiracies, mass conspiracies, huge conspiracies,” Steve counters, passing me the spliff. “We’re under some bigger control at this point, and there’s a lot more going on than we know.” When the smoke hits my brain, I can almost see the plots thicken. I ask him how Goa differs from the raves in England. “Here people know about the history of freakdom, of free-form living. That vibe is carried forward with the music. In England it’s not really freaky anymore. It’s too organized. People are wearing the right kind of T-shirts, whereas here people will rip their T-shirts apart and run down the beach.”

As the early sunlight streaks the sky, I leave the duo and head back to the dancefloor. Dawn is Goa’s sweetest moment. The bpms slow, and the night’s bracing attack gives way to a smoother, narcotic trance. According to Goa’s more shamanic DJs, the change of pace has a ritual function: after “destroying the ego” with the night’s hardcore sounds, “morning music” fills the void with light.

The dawn light floats through the clearing like incense, and a deep resonating chant emerges on top of the lush, succulent beats: “Om Namah Shivaya.” It’s a mantra devoted to Shiva, the Hindu god of tantric transformation and hence something of a freak favorite. Slowly, a Benetton ad’s worth of folks emerge

from the gloom: Australians, Italians, Indians; Africans in designer sweatshirts, Japanese in kimonos, Israelis in polka-dot overalls. A crowd of old-time Goan hippies ring the clearing, grey-haired and beaded creatures who dragged themselves out of bed just to taste this moment. As the dust fills my nostrils, I wonder whether Goa’s raves were much more than digitally remastered Be-Ins. Maybe something far more strange and ancient than beatnik dreams of the East was entrancing this crowd, something these old-timers knew but would not say. One thing was sure: Goa’s underground was deep, and I was sinking.

***

As an Indian pothead I met in Mysore put it, “Goa isn’t India.” And Goa hasn’t really been India since the Portuguese first colonized the place in the 1600s, when “Golden Goa” became a place a European man could really go to seed. Inter-breeding with the somewhat pagan locals was encouraged, and some adulterous Indian wives took to dosing their husbands with datura weed, rendering the men, as one early account put it, “giddy and insensible.”

Goa remained in Portuguese hands until India seized it back in 1961, and the region was still more European than Asian in flavor when beatniks discovered its beautiful beaches a few years later. By the end of the ’60s, hundreds of thousands of European and American freaks were streaming overland into South Asia, trying to find themselves in a country where it’s easy to get lost. Though Goan beaches like Calangute and Baga didn’t offer electricity, restaurants or much shelter, they did provide sweet relief from the overwhelming grind of travel in the East. Every winter a motley tribe of yoga freaks, hash-heads and art smugglers would gather, until the growing heat and the threat of the summer monsoon pushed them further on. Goa was like going home for the holidays, and the freaks celebrated: Christmas, New Year’s, and especially full moons.

I asked one grey-haired French Canadian freak about these backwater bacchanals. He hadn’t been in Goa since the ’70s, but was passing through after returning his dead Tibetan lama’s ashes to Dharamsala. “They were very free” he said, raising a lascivious eyebrow. Free enough to have the local Catholic nuns up in arms, scandalized by orgies and nudity and rumors of hippy waifs breastfeeding monkeys. Less than a decade after the Portuguese finally left Goa, the land had been invaded by Christian Europe’s footloose pagan spawn.

But by the time I arrived, underground Goa was well on its way towards becoming a bohemian Club Med nestled amidst rice patties and palm trees. As any Lonely Planet guidebook will tell you, Anjuna is one of Goa’s last hippie hold-outs, but most of Anjuna’s available housing had been rented out by regulars months before. After hours of wandering along cool sandy paths, I found a two-dollar room: a mat on a stone floor, no windows, a bare bulb. Hunkered down next door was a crew of vacationing Indian men, drawn like many middle-class Indians to purview Goa’s exotic (and frequently bare-chested) freak fauna. They sold Compaq computers to missile developers in Hyderabad, a full day’s drive to the east. “We like the hippies! They’re in their own world! Do you know where the party is?!”

With its bucket shower, scorpions, and outhouse (not much more than a chute into a pig trough), my abode was hardly plush. But like the saddle-sores you might get at a dude-ranch, such rough edges keep the straight tourists at bay and add an adventurous texture to the delicious lethargy that Anjuna otherwise affords: free parties, great drugs, jumbo prawns, cold beer, cool bikes for rent.

Along with Xavier’s restaurant, where the beatnik pioneer Eight-Finger Eddie sits every night like some ancient mariner, Anjuna’s greatest tourist draw is its Wednesday flea market. What began decades earlier as a lazy venue for local vendors and destitute hippies has swollen into a glorious seaside mall. Wandering past acres of blankets and bangles, vests and singing bowls, spices and raw chunks of amber, I felt like some reincarnated Portuguese trader armed with American Express. The freaks have their own section, where travelers sell blank DAT tapes and Drum, Stussy tank-tops and original rave-ware. I wasn’t surprised when an expatriot American fashion photographer told me that some of the East’s traveling technofreak designers made up to a 1000 dollars a day on the streets of Tokyo, money they just poured back into their nomadic drift.

***

Goa is only one stop on the hippy trail that three decades of drop-outs, drug lovers and mystical travellers have carved into the East. But Goa is perhaps the only boho roost where techno is as ubiquitous as faded blue jeans. The digital beats seep out of half the houses and all the cafes, morning, noon and night. In three weeks time, I heard Pink Floyd once. I did not see one acoustic guitar.

For a certain underground breed of DJ, Goa is an esoteric Mecca, and they flock from every corner of the globe—New Zealand, Japan, Israel, Italy, France. Established music-makers arrive with their fall crop of trance tracks for exchange and tasting, while rising stars train like athletes and perform more for their fellow DJs than the crowd. The Orb’s Alex Patterson has passed through, the famed London remixer Youth is a regular, and Sven Väth—Frankfurt’s techno Kaiser—fell in love with the place.

I run into Väth at the Shore Bar, an open-air seaside cafe with the ambience of Amsterdam-by-the-beach. It’s dusk, and the sun slips like a swollen egg into the Arabian Sea as fishing trawlers crawl along the horizon. With his pale bald dome, soul patch and slightly devilish eyes, Väth looks like a techno Mephisto. As an acid jazz take of “I’m In With the In Crowd” bubbles in the background, Väth tells me how surprised he was with Goa’s hip musical edge when he first visited a few years ago. “One of the first Goa DJs, Laurent, came up and said how much they liked my early, 16-bit recordings. Hardly anybody knows those records!”

Väth’s been back to India every year since. On his previous visit, he he recorded DAT samples which showed up on Accident In Paradise, whose greatest cuts are now in regular rotation. “The Goa sound is a very special deep trance,” Väth says. “Its a serious thing. These people are not kids, this music is a part of their lives. Now when I produce or DJ in Frankfurt, I try to give the people there this kind of feeling. In India I fill my energy, and in Europe I put it out.” This year, Väth lugged 150 kilos of turntables and vinyl into India just so he could make a real Goa party.

DJs are the maestros of the information age, and not just because the discs they spin are basically digital creations. Freed from the gravity of faces and fixed names, underground dance music finds its essence in constant mutation and total overproduction. Sifting through hundreds of records a week, DJs define themselves in part by what they comb out of the data overload. That’s why many act like spies, taping over record labels, or buying all available copies of a favorite record and destroying all but one. DJs are made of information. But in Goa, where the inability to mix makes selection particularly important, they drop their guard and swap tapes.

A few of those tapes are brewed locally. Johan is a young German producer who looks like Anthony Kiedis with a brain. He lives in a huge house in a small inland village, his room containing little more than a bed, a bhatik print and his gear: Macintosh PowerBook, Akai sampler, keyboard, DAT deck. I’d heard two of Johan’s intense tracks on the Dragonfly label’s Project II Trance (under the name Mandra Gora), which along with Juno Reactor’s Transmissions and the Ethnotechno and Concept in Dance compilations, is the best stateside introduction to Goan trance. But Johan doesn’t like to DJ—he’s one of those hardcore power dancers who treat the night as one long track. “With a combination of good music, a good spot and good dancing, it’s like a cosmic trigger goes off,” he says of Goa’s greatest rites. After a night of cosmic gyration, Johan would return to his studio, download his vibes, dump the bytes onto DAT, and slap the tape onto his DJ friends. “It was like a perfect feedback loop.”

When Johan first arrived in Goa six years ago, the techno-trance scene was totally off the map. Synchronicities abounded. “It was like a poker game no-one could follow.” But these days he’s starting to sell his stuff in the West, and though he plans on setting up a large Goa studio as soon as he can figure out the right bureaucrat to bribe, he’s pessimistic about the future of the East’s nomadic underground. “Soon we’ll have a global digital network where everyone will know where everybody is all the time.” He looks me in the eye as only a German can. “What you’re here to write about is already dead and gone.”

***

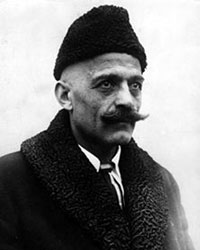

Väth and Johan are friendly enough guys, but many Shore Bar insiders set themselves apart from the rave tourists (and journalists) with the same kind of snobbery you find in London or New York. Given the mystical legacy of freak India, the cliques here have a mystical air, like they’re pushing the envelope of consciousness itself. As Raja Ram, an old moustached prog rocker-cum-techno musician, told me, “You have to become a neuro-naut to understand this music. We’ve gone from flint-rock to the moonlanding in a few thousand years, and now we’re on the edge of the world opened up with information machines. This is a new inner space we’re exploring.”

One of these inner astronauts is Ollie Wisdom, whose Bamboo Forest party was the best of the season. Ollie’s one of Goa’s rising stars, an ex-Goth from a circus family who learned the DJ ropes on the Thai island of Koh-pang-gan.

I had decided not to artificially stimulate myself for his party, so I crawled into bed, setting the alarm for 5 am. But the Bamboo Forest was only a few hundred yards away, and the bass beats warped my dreams. Two glowing Tibetan eyes appeared before me in the dark room, and led me up a moonlit mountain path to an old, white-bearded yogi. He said that reality was like a television set, and then he showed me how to channel-surf. I zapped between technicolor twilight zones until a great metaphysical boredom set in. “Techno is the sound of the universe being created and destroyed every second,” he said.

I woke up woozy as hell, but dragged myself out of bed and headed down the jungle path, past cool, dark trees and rows of Enfield bikes and mopeds. Rounding a large banyan tree, I found a Mad Hatter’s acid test of a party: banners of Shiva and blaxploitation hussies hung in the breeze; patches of bamboo coated with a rainbow swath of luminescent paint glowed in the black light; a phallic purple pillar stood in the center of the dancefloor, crowned with a pumpkin-sized quartz crystal. As hardcore techno pounded, someone set a large wooden pentagram on fire, and in the witchy light I could see a large pyramid lashed together with bamboo in the distance. From inside, Ollie lorded over the crowd, decked out in shiny silver pants and Jetsons shades. He rolled his hips, flipped through DATs, pressed buttons like a neuromancer.

When Ollie’s final cut faded around 11 am, I picked my way through the iridescent bushes and approached him with notebook in hand. Bad move. He was sitting in a circle outside the DJ hut, sharing a smoke with a man whose short hair was twisted up into two chartreuse Martian devil-horns. I asked if I could set up an interview. He and his friends turned on me with maniacal disgust, like I was a Mormon covered with dogshit. “Nooooo! Go away!”

***

One DJ I did manage to nail down was Gil, the dread-headed Kris Kringle who spun at the hilltop party. When he DJs in San Francisco and other Western cities during the summer monsoon, he’s known as Goa Gil—only one of the items that makes Gil less than well-loved by today’s younger DJs. Gil lives in a spacious brick house behind the Orange Boom restaurant and alongside a pile of rubble he calls a temple. “Come in, come in,” he barks before I even introduce myself. A large collage of rave flyers, psychedelic posters and photos of Hindu holy men covers one wall.

Just as I start to get comfortable, Gil’s pretty young French wife Ariane—herself the child of Goan freaks—begins interrogating me. “Why are you writing an article for? You’re going to spoil everything.” She complains about a piece in iD magazine that resulted in floods of Brits. “Now we get the Americans and all the hip-hoppers coming,” she whined. I assure her that the hip-hoppers have other things on their mind. She grabs her sunglasses, and storms off to the beach.

But Gil knows he has a story to tell, so he tells it. Growing up in Marin County in the ’60s, Gil took the bus down to the Haight after school. He fell in with Family Dog, the loose freak collective who sparked the psychedelic concert scene before Bill Graham moved in with dollar signs in his eyes. In 69, fed up with “rip-offs and junkies and speed freaks,” Gil bought a one-way ticket to Amsterdam. He then made his way overland to India, where, among other things, he discovered the sadhus.

Hymns in the ancient Vedas describe these wandering holy men as longhaired sages who lived off the forest, covered themselves with ash and drank the elixir of the gods. Today, some of India’s hundreds of thousands of sadhus are strict ascetics, some are simply beggars, and some resemble Hindu Rastafarians. These impressive, bloodshot souls wander about, wearing their hair in long dreads and finding spiritual sustenance in charas, India’s yummy mountain hash. Before they smoke the clay pipes called chillum, the sadhus cry out “Bum Shiva!” the way Rastas bark “Jah!”

Not surprisingly, the freaks took to the sadhus. Gil went whole hog, living in caves, wearing orange robes, and coaxing the Kundalini up his spine. But he still found his way to Goa’s firelit drum circles every winter. Despite persistent false rumors that the Who or the Stones or the Beatles left their gear on the sands of Calangute, the source of Goa’s music machines was a fellow named Alan Zion, who smuggled in a Fender PA and two tape decks overland.

According to Gil, these parties are the direct ancestors of raves. Techno historians already know that English working-class kids brought raves back from Ibiza, the cheap vacation island off of Spain whose weather, slack and lack of extradition treaties made it a Goa-style hippy colony decades ago. While many DJs shuttled between Ibizan summers and Goan winters, some claim that the more authentic lineage of electronic ecstasy belonged to the East. As Genesis P. Orridge put it, “The music from Ibiza was more horny disco, while Goa was more psychedelic and tribal. In Goa, the music was the facilitator of devotional experience. It was just functional, just to make that other state happen.”

And Goa went totally electronic in 1983, when two French DJs named Fred and Laurent got sick of rock music and reggae. At the same time Derrick May and Juan Atkins created the futuristic disco-funk called “techno”, Fred and Laurent used far more primitive tech — two cassette decks — to create a schizo’s brew out of New Wave, electronic rock, gay Eurodisco and experimental industrial bands like Cabaret Voltaire and the Residents. They slipped electro-pop like New Order and Blanc Mange into the mix, but only after cutting out all the vocals. It was heady shit, and soon hipsters started slipping them underground tapes from the West.

Gil and his friend Swiss Ruedi quickly joined in, but the techno transition was not smooth. The freaks were attached to their Bob Marley, their Santana, their Stones. Ruedi had to enlist a bodyguard to ward off some rock fan’s blows.

“How can you listen to the same music for 15 years?” Gil now booms. “I used to love the Dead when I was growing up, but I can’t listen to that stuff anymore. It sounds like cowboy music.” Gil thinks that music is always flowering, but that the juice moves through different genres, always one step ahead of the record companies. “Now it’s in techno. Music has gone through a complete cycle. It started in ancient times with tribal drumming, and now it’s come back to tribal trance techno. Where do you go from there?”

Gil starts pacing about, wildly gesticulating. “I’m basically just using this whole party situation as a medium to do magic, to remake the tribal pagan ritual for the 21st century. It’s not just a disco under the coconut trees.” He pauses to light up a Dunhill. “It’s an initiation.”

Gil slaps on two remixes he made while visiting San Francisco. The band is Kode IV, a German duo who brag about producing tracks in five minutes and which Gil was to join later in the year after one of the members died. He blasts the tunes, and towers over me as he identifies the samples: a sadhu’s “Bum!”, the Pope, Aleister Crowley. Then he plays the “Anjuna” remix of the cut “Accelerate,” towering over me as he repeats word for word a long sample cribbed from some flying saucer movie: “‘People of the earth, attention’,” he booms over the beat. His eyes bore into mine, and for a moment I feel like he’s channelling the message to me directly from the aliens, like I’m finally getting the key to Goa’s surreal scene. “‘This is a voice speaking to you from thousands of miles beyond your planet. This could be the beginning of the end of the human race.'”

Ariane walks in, breaks the spell and bad vibes me out of the house. Gil follows me outside, trying to explain the reasons for her underground protectionism: the rising pollution, the clueless young DJs, the sharp rise in

prices. Gil shakes his head. “We came here so long ago, to the end of a dirt road and a deserted beach. It was like the end of the world. And now the whole world is at our doorstep. The communications lines are open. Where do we go from here?”

***

If Gil had listened a little harder to the music he loves to spin, he would have seen it all coming, because techno is the sound of one world shrinking. The media tsunami that gave backwater hippies like him DAT players and computerized music has also brought fax machines and MTV and journalists to their hideaway. Gil’s stuck in the paradox of the technofreak: you can’t drop out and plug in at the same time. The underground is now networked, and you can’t escape the feedback loop for long. You might even call it karma.

British club kids can now fly straight to Goa for around 500 bucks, and many arrive with nothing more than cash in their pockets, suitcases stuffed with party clothes and a desire to get “off their face.” They care nothing for India, it’s art or music or deep spirituality, and what had been a magical release valve for expatriots intoxicated by the East has become a thing in itself. “These new people have no idea,” one silver-haired French sarod player who first came to Goa in the early ’70s told me. “They didn’t come overland, they didn’t have to find their own food, and they never really got lost.”

Most of Asia’s hardcore gypsy freaks don’t come this way anymore. They’ve drifted far south, to primitive spots not listed in the Lonely Planet guidebook. At the same time, Goa’s state and local government have begun maneuvering for tonier tourists and five-star hotels, even though many locals prefer to get their rupees straight from the relatively non-invasive freaks. As the cops crack down on drugs and parties, Goa’s underground is caving in. All this scene really needs is great weather, weak currency and a degree of invisibility (or permeable law enforcement). Goa-style parties have already popped up in Bali, Thailand, Australia and the valleys of the Himalaya. But as the grid invades Anjuna, one of the last pockets of freakdom’s mystical and stridently non-commercial trance-dance culture will fade away like the moon at dawn.

***

I decided to hunt down Laurent, the French DJ who had pioneered the electronic parties back in ’83 and had alternately been described to me as a burn-out and a genius. Gil hadn’t been too encouraging. “He probably won’t talk to you. He’s very mysterious.” But he told me where Laurent could be found every day: in the last chai shop on little Vagator, playing backgammon.

So I puttered my unhip little TVS moped towards the cliffs overlooking the lush coves of Vagator beach. I clamored down bluffs packed with coconut trees and tall hippy teepees, marveling that the temporary shelters of the nomads the Europeans called “Indians” were now housing European nomads in India.

Down on the sand, a scruffy Rajasthani man was giving camel rides to blond kids with names like Shakti, while their bronzed parents played paddle-ball or soaked up the rays. Packs of young fully-clad Indian men strolled by, middle-class guys from Bombay who piled on Goan tour buses for the sole purpose of glimpsing European tit. I watched their sheepish, furtive eyes; I watched the sun-bathing tourists pretending they hadn’t themselves become a tourist attraction.

The last chai shop on the beach was a grimy hut filled with folks who looked as weather-beaten as the long wooden tables they hunched over. Some played backgammon, others sipped orange juice and chai, and everyone smoked like the Amazon. A sour-faced Indian girl serving up a bowl of porridge and honey pointed to Laurent: a scrawny guy in a Japanese print T-shirt, tossing a pair of dice. Gaunt and bloodshot, his teeth stained and bent, the man looked like a hungry ghost.

Laurent gave a caustic laugh when I asked to interview him. While we talked, he kept slapping the tiles with his partner, a balding, middle-aged Brit named Lenny. “Art does not pay so I am forced to gamble,” he explained in a throaty Parisian accent thick with sarcasm. He fiddled with my Sony mini-tape recorder, clearly bent on soaking this little episode for all the humor it was worth.

“The spy in the chai shop,” mused Lenny as he drew heavily on a cigarette. Laurent cracked up, his laugh quickly degenerating into an asthmatic coughing fit.

“You know, it used to be very bad here for spies,” Laurent said, with a cocked eyebrow indicating mocking concern. I couldn’t tell, but it seemed like he was referring to two journalists who had been slipped heavy knock-out drugs some years before.

Despite his heavy sarcasm, creepy laughs, and constant hints that he’d tell me more if I gave him a lot of money, I took a liking to Laurent. He reasserted Goa’s contribution to rave culture—”This is the source of the source”—but he was low-key about it all. No mysticism, no nostalgia. He gave his friend Fred the credit for first mixing electronic tapes at the parties, but said his friend’s style was too bizarre for the crowds. “Nobody liked it. Then I played and made it so people liked it. And now people like it all over the world.”

Laurent paused, and looked me in the eye. “Here you make parties for very heavy tripping people who have been traveling all over the place. You have to take drugs to understand the scene here, what people are thinking.”

Some pals walked over, and Laurent began to carry on three conversations in three different languages. Meanwhile, the game with Lenny came to a head, and Laurent was losing. He stood up, rolling the dice with macabre drama.

I was getting frustrated. Could this sarcastic wraith gambling for pennies in a burned-out shack be the father of raves? One tale I heard had it that Laurent got his start DJing because he had been an unrepentant leech. Figuring to put him to good use, someone handed him a tape deck and said “Make party music.” And the same source said that Laurent was the most brilliant DJ he’d ever heard, doing things with cassette tapes that blew away most vinyl-spinning DJs in the West.

Laurent let slip that he still had some of his early party tapes, and I pressed to hear them. “Ah, this would be very, very expensive,” he said, curling his lip. “We must draw up a contract.” Then he turned away from me and racked up another game.

***

One hazy, hot afternoon, I was hanging around the Speedy Travel agency waiting for a fax. A steady stream of freaks bought tickets for Hampi. “It is a very ancient place,” a bronzed Dutchman rolling a Drum told me, describing what sounded like a Hindu Stonehenge 300 kilometers to the east. “I hear some German with a bus will throw a full moon party in the temple there.”

So a week or so later, a creaking local bus spits me out at Hampi Bazaar. I’m worn to the bone. The dusty main street is lined with trinket shops, cheap restaurants, and packs of sad-eyed kids with their outstretched hands and mantras of “Rupee! Pen! Chocolate!” At the end of the bazaar stands a massive 160-foot gopuram, a gaudy pyramid with the melted curves of a drip sand-castle.

Hampi is not quite an “ancient” place—the Hindu city fell to rampaging Moslems during Queen Elizabeth’s reign. But the ruins that spread out for miles around the small, freak-filled village exude a haunting, archaic calm. Green parakeets roost in silent temples encrusted with jesters and monkey gods. Rice paddies line the nearby Tunghabhadra river, which snakes past huge mounds of desert boulders. Across the river, a number of sadhus tend Shiva shrines and pass the pipe with hearty Caucasians who have turned their backs on the minimal comforts of the village and gone totally caveman.

Hampi is far mellower than Anjuna. I waste away my afternoons flopped out on the shaded mats at the Mango Tree, a peaceful outdoor cafe on the banks of the lazy river. The cafe’s mandatory “Smoking Psychotropic Drugs Not Allowed” sign is cloaked by a poster, so all you can see is the word “Smoking.” Sometimes the Caucasian sadhus from across the river show up, with their orange robes and mala beads and fading biker tattoos.

But a few days before the full moon, a noticeably trendier crowd moves into town: nattier threads, better cheekbones. Rooms fill to capacity, kids sleep on roofs or in temples. Finally a huge tour bus drives up and parks in the dusty bazaar. Slogans blaze across the side: Techno Tourgon, LSD 25, Shiva Space Age Technology. Jörg the DJ has arrived.

When I finally catch up with Jörg, it’s the day of the full moon. “Come in, come in,” he says as I climb onboard. The BBC has just finished interviewing him, and the man is beaming, his blue eyes glowing with an intense lucidity. A huge dancing Shiva statue dominates the dashboard, and Jörg’s taut naked belly is tattooed with an image of the Shaivite yogi Shankar.

Jörg is pure freak, too maniacally enthusiastic to cop a snobbish DJ attitude. “I used to be a typical heavy-metal rock’n’roller. Now I am addicted to techno,” he says in his heavy German accent. “For five years time now I listen to nothing else. Except meditation songs in the morning.”

Like many technofreaks, Jörg’s first Goa party was nothing less than a conversion experience. “You can laugh, but it was like seeing a keyhole to God,” he says in a hoarse voice. He’s been back and forth to India ever since, selling land cruiser parts at the Chinese border, DJing parties around Kathmandu, dipping in the Ganges with the sadhus at the holy city of Haridwar. The last time he made the overland trip from the West, he was cruising through Iran in the middle of the night, trance blasting, multi-colored lights flashing along the side of his Techno Tourgon. The police pulled him over. He stepped out the door, wearing a pair of goggles ringed with blinking lights. They trained machine guns on him.

It dawns on me that Jörg is in some fundamental sense insane. But like a reincarnated Merry Prankster, he rides his lunacy the way he guides his bus along India’s suicidal roads—with spontaneous grace.

“I’m a little bit extremist,” he admits, grabbing a cigarette from a pack lying next to a crumpled photo of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. The previous year, after a month in Goa packed with drugs and dancing, and with hardly any DJing experience, Jörg set up his gear in Hampi’s underground Shiva temple and threw the archaeological area’s first rave. “After that party I feel like this big hole. I sat for another month under a tree. Nothing inside anymore.” He fiddles with the 5-inch Sony mini-discs he uses instead of DATs. “But believe me, to be empty and open to everything is exactly the right position when you come to India. You have to improvise.”

And today, just hours before moonrise, Jörg’s still improvising. After spending days finding the right official to bribe in order to throw a party, he made his case. “We talked for hours. We got to know each other very well. Then he said no.”

So in the fading sunlight, Jörg decides to cross the river into another district. He and his crew lug their gear down the river’s edge, and load the equipment into the same round, leather-covered basket boats the Portuguese explorer Paes noted when he passed through Hampi in the 16th century. Darkness descends upon the freaks, and they have no idea where they’re going.

Hours later, hundreds of us ferry across the river in the same leaky boats. We thread our way past crumbling walls and along paths lined with ominous palms, following a trail of lanterns a mile or so onto a treeless plateau of moony rock. We glimpse black lights in the distance, hear the dull thud of techno. No chai ladies tonight. We’re partying in Bedrock.

Jörg crouches over his machines beside a large boulder dry-painted with the appropriate symbols for the night: peace, OM, anarchy. Though his music was old, his mixing rough and his generator tepid, Jörg soon sinks the dancers into the groove. I start taking snapshots. Unlike Goa, where blissed-out hippies can transform into ferocious assholes at the sight of a camera, nobody seems to care. An Indian sadhu passes through the crowd, talking with a grizzled Italian in orange robes who occasionally whipped out a conch shell and blew. Who is the holy man? I wonder. Who is the pothead?

After a bug-eyed Jörg leads us careening through an eon’s worth of cartoon wormholes, dawn finally arrives, dusting the rocks with pale purples and rusty reds. Fairy-tale temples emerge in the distant mist, but it’s no

hallucination. Jörg climbs up on a rock and pumps his fist, exhorting us into a supreme embrace of the moment. It is night-time, daytime, alltime, and as the rising sun and the setting moon touch the horizons on either side of us, the heavenly bodies perfectly balance the land on which we dance. Like great sex, great parties move the earth.

I climb up some huge boulders to get a view of the high and wholly bizarre scene. A young Japanese man with a bandana sits smoking atop a slightly unsteady rock. “Go slow,” he softly warns as I sit down gingerly on the rock face. “Go natural.” Abé lives in Tokyo, but doesn’t like it much. “People forget nature-mind,” he says, gesturing above to the morning’s crystal blue dome.

Then it hits me. There’s nothing “natural” about the sounds echoing off the rocks. These melodies and beats are created, recorded, and reproduced in the digital ether of micro-circuitry. Techno’s frenetic datadense intensity seems totally contrary to Abé’s air of bodhisattva calm. “So do you really like this music?” I ask him.

“Yes,” he says, tapping a hollowed-out coconut mixing bowl hanging from his neck. “I like primitive sounds.”

And that’s the paradox of the techno-freak. As we hurtle into the 21st century, these transient refugees from the First World have poached the info tech that’s speeding up the march of progress and made an abrupt about-face towards the archaic. Technology is mobile, so they drag it to the rocks and jungles. Technology loves connection, so they sync it with the ancient wheel of the heavens. Technology simulates, so they make it mimic the fear and splendor of shamanic trance. The Goan beaches that spawned this ecstatic digital primitivism may be lost to media hype and packaged tours, but the hardcore technofreaks will just lose themselves in the porous landscape of the developing world. After all, the full moon follows you everywhere you go.