An early aughts overview

Drug books occupy a curious niche in the world of letters. My local bookshop calls their section “Altered States,” and its volumes range promiscuously between history, mysticism, natural science, user manuals, social policy and poetry. Drugs may be the ultimate object of interdisciplinary studies. What other field can encompass Alan Watts and Irvine Welsh, Walter Benjamin essays and Advanced Techniques of Clandestine Psychedelic & Amphetamine Manufacture?

This diversity of perspectives makes sense, and not just because drugs themselves are such shifty characters. Drugs are mercurial because of our own desire — specifically, the perennial human hunger for euphoria, intensity, transcendence. This leads to what you could call spiritual hedonism — a paradoxical desire, at the very least, explains the links drug lit shares with both erotica and the occult. In all three genres, heroic experimentalists wager madness and obsession in the quest for insight and pleasure, while languages both technical and seductive detail psycho-physical techniques that promise transformation, or at least flights of fancy. And behind it all, driving the delicious frisson, is the absurd but suggestive gap between experience and the written word.

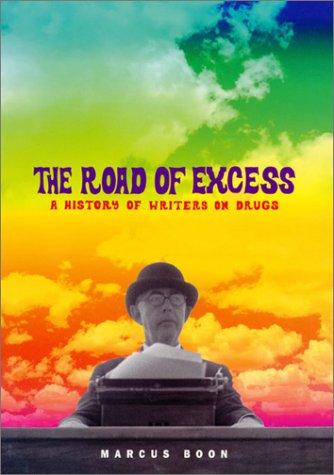

This is where literature proper steps up to the plate. As Marcus Boon shows in his marvelous The Road of Excess: A History of Writers on Drugs, literature has long played a powerful role in our basic understanding and experience of drugs. Because the “inside” of the high is irreducibly subjective, we need poetry as much as the technical discussion of cultivars and indole rings. At the same time, Boon’s book reveals some of our most imaginative literature to be embedded in botanical and chemical encounters that exist, in some sense, beyond the flickering firelight of signs.

Boon knows that the personality of substances is at least as important as the personalities that gobble them, and so he has divided his tale into discrete sections on narcotics, anesthetics, cannabis, stimulants, and psychedelics. In each section, drugs and the literary imagination shape each other until the boundaries begin to wobble. British poets huffed some of the first bags of nitrous oxide, while the earliest scientific studies of mescaline dug into Goethe and the Book of Ezekiel in order to characterize the fireworks. When Harry Anslinger first moved to criminalize marijuana in the 1930s, he cited the notorious tale of Hassan-I-Sabbah and his hash-head assassins — a story that first appeared in Marco Polo and was linked by dubious etymology to cannabis in the early nineteenth century, when French bohemians thrilled to the countercultural implications of the tale.

Inevitably, Boon covers some familiar ground here, particularly in light of Sadie Plant’s wild and tantalizing Writing on Drugs and Mike Jay’s recent Emperors of Dreams, a history of drugs in the nineteenth century that showed that behind every addled poet lay an equally wacked scientist. Still, Boon has written the most useful and engaging history of psychoactive lit yet. His prose is generous, unhurried, and far too tasteful to gob up the page with theory. At the same time, Boon casts his net deep and wide, drawing in folks as disparate as Chaucer, Kant, and Iceberg Slim.

Boon is not content to simply record the encounter between modern writers and drugs; he deepens the story as well, and, amazingly, he does it without exploiting the rhetoric of personal experience or subversive hip. In other words, Boon takes drugs seriously without, in any obvious sense, taking them. He reaches a rare place of detached empathy for the drug experience, and his perspective is often profound:

The dreams of the cannabis user are not gnostic; they do not withdraw into the darkness of another world. These dreams are developed out of the social space that the user finds himself or herself in. Of course, it is likely that the user will simply giggle at these dreams, or run from them in a fit of paranoia. But there also exists the possibility of acting on them.

Thankfully, Boon does not resist the temptation to dish: Balzac logged 50,000 cups of joe in his life, Theodor Dreiser wrote far too knowingly about nitrous oxide, and Proust gobbled sedatives and barbiturates that he offset with subcutaneous injections of adrenaline. Don’t mistake this information for simple cause-and-effect: elsewhere Boon points out that some classic drug texts that are routinely taken as case studies, like Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater or Théophile Gautier’s “Le Club des Hachichins,” are essentially fictions. But Boon does want to argue that if we are going to accept writing as a material production, then we gotta give those molecules some credit too. When Allen Ginsberg finished writing Howl on peyote, he wasn’t the only one howling.

Though Boon has some revelatory things to say about anesthetics — “the only drugs for which the major cultural reference points are Hegel and transcendental philosophy”– his best chapter concerns psychedelics. In traditional societies, substances like mushrooms or ayahuasca open the gateway to nature’s nonhuman spirit realms. Boon shows how, for the West, literature opened the door into the psychedelic realms. After all, as Boon points out, western literature itself emerged from Christianity’s fascinated but frightened Renaissance encounter with the “imaginal realm” of classic paganism — a realm whose “deities, festivities, and vision-inducing plants” were then kept alive but contained within the relative safety of the text. Today we are still bumbling about that Renaissance wood, alternately fascinated and terrified by weird plants and powders that mediate our fears and attractions towards God, sex, and crime. As well as raising practical issues that all of us face in our increasingly psychoactive society, drugs are still a literary conundrum. As Boon insists, they remain allegorical: devices of meaning as well as chemical change. These meanings demand to be read, not the way one reads an incriminating sample of urine, but the way one reads tea leaves.

Enter Dale Pendell. A California poet and ethnobotanist who brews a mean wormwood mouthwash, Pendell has just published Pharmako/Dynamis, the second of three projected volumes that explore, like nothing else I know, the human interaction with psychoactive substances. Like Boon, Pendell places drugs at the cross-roads of various discourses, only he does so like a Beat alchemist working textual DJ decks. Dense paragraphs devoted to ephedrine isomers are followed by political rants and erudite arguments about Vedic religion. Quirky, dreamlike readings of Genesis or Faust are interspersed with recipes for Tuscan chocolate or freebase cocaine. And poetry keeps popping up among the marvelous illustrations, especially in Pendell’s oracular stabs at phenomenology — in his last volume, Pharmako/Poeia, Pendell memorably described the odor of opium as “the smell of the food that the dead eat.”

Pendell’s chorus of voices are themselves occasionally interrupted by another voice, an italicized imp who pokes fun at the author’s efforts and conclusions. This is the voice of the ally, a crucial term for Pendell and many of today’s psychonauts. The idea here is that consuming psychoactive plants or molecules — including things like tobacco and coffee — means forming a relationship with the those compounds. There are crushes and spats, hidden agendas, and personalities on both sides of the equation (the ally is often something of a trickster). Though it might sound like reheated Carlos Castaneda romanticism, the concept of the ally actually helps get us out of our internal stories. Drugs aren’t just social constructions: they are powerful emissaries from the molecular world that everywhere surrounds our not so independent minds, the world where, as Pendell says, “winds and ocean currents are intersynaptic fluids.”

Though we do it more than we admit, many of us have little interest in making deliberate pacts with chemical sprites. But for those rare psychonauts who hear the call, the secret garden can only be explored by nibbling and sniffing your way through it. Pendell calls this the Poison Path, a “vegetable alchemy” that combines the grounded self-experimentation of any honest scientist with a street-smart spiritual heterodoxy that risks “the seduction of angels.”

Pendell is catholic in his tastes. While his first book covered obvious contenders like cannabis, opium, and the deeply weird Salvia divinorum, his new volume is principally devoted to stimulants, or what he calls “Excitantia.” Pendell begins with our morning beverages, alights on exotica like betel and khat, and then ramps it up to coke and amphetamine, before closing with a section devoted to “Empathogenica” like MDMA and GHB. Pharmako-Dynamis pays more attention to history and politics and less to the voices of the allies, but that’s because we have so thoroughly assimilated these voices into our excited culture, not because they aren’t whispering. Every office has its shrine to the coffee god, but we think it’s just fuel.

Indeed, the pragmatism of the stimulants, that can-do spirit of mental fortitude, has ensorcelled modern society. The Enlightenment itself was chemically enhanced, with Voltaire its paradigmatic “coffee-shaman,” downing seventy-two cups a day. The desire to sweeten speedy beverages drove Europe to plunder Africa, just as earlier stimulant civilizations, like the Aztec and the Inca, showed a taste for blood-thirsty imperialism. Behind the botany of desire lies the botany of conflict. “If we accept the world as the playground, sometimes battlefield, of poisons, history becomes a story of shamanic alliance and conflict, a story of magic spells and their dissolution by new spells.”

Speed has become “our principal and ruling poison,” and that only shows how poisoned the path can get for both cultures and individuals. Appropriately, Pendell finishes the section on Excitantia with a fragmentary prose poem on freebase mania called “Stealing from Tomorrow,” his most explicit writing yet on the dark side of drugs. He follows this, as a good Californian should, with a fragmentary account of a vision-quest in the High Sierras. He invokes a “a hunger for transcendence that borders on lust.” It’s a decisive turn away from the culture of speed, as well as a preview for the final book in Pendell’s trilogy, Pharmako/Gnosis, in which the psychedelics will have their say.

Though I have no doubt that Pendell will rise to the occasion, writing about psychedelics isn’t easy. The numinous ferocity of psychedelic experience demands visionary language, and yet most attempts are as compelling as bad SciFi or a stranger’s dream journal. At the same time, the sober approach, which uses the reasoned tones of psychology and comparative religion to carve out a fragile zone of legitimacy around the topic, often falls flat. For example, the new collection Hallucinogens: A Reader, edited by UCLA School of Medicine doc Charles Grob, gathers solid reports filed over the last decade from therapists, scientists, and respectable heads like Andrew Weil and Huston Smith. Grob is aiming at smart, button-down readers, and, for what it’s worth, he has truth on his side. But it’s basically boring. One waits in vain for Rintrah’s roar.

I’m happy to say that Daniel Pinchbeck’s Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journal into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism roars. On the surface, the book presents an intimate investigation of today’s psychedelic culture by a skeptical but intrigued Manhattan hipster undergoing a spiritual crisis. Thankfully, the book is no mere memoir: Pinchbeck blends reportage, historical survey, and critical analysis with his own rather anxious and compulsive quest. But what starts out as smart if breezy first-person journalism soon goes marvelously, perhaps disturbingly awry, as Pinchbeck slips through the cracks of the world and finds himself, with faculties largely intact, on the far side of the looking glass.

Along the way, Pinchbeck gives us a solid survey of current psychedelic culture. He visits the Bwiti in Gabon to consume iboga, a powerful root that tastes like “sawdust laced with battery acid” and rockets him back to, of all places, his New York apartment. He goes on an Amazonian ayahuasca tourist jaunt, and spends the obligatory week cavorting around Burning Man. Pinchbeck has too jaded an eye to romanticize these expeditions, and he draws on thinkers as diverse as Barthes, Benjamin and Michael Taussig to build critical context for his experiences, which grow increasingly powerful and odd. By the end of the book he is snorting the “postmodern demonic MTV psychedelic” DPT and running around his apartment exorcising demons with a stripper he met in Palenque.

In other words, consensus reality begins to lose its hold. Pinchbeck discovers that things like telepathy, subtle energy fields, and Gurdjieffean cosmology begin to make more sense than the New York Times. He comes to suspect that iboga and ayahuasca are actually extradimensional intelligences intervening in human affairs. His questions become more cataclysmic in their implications. “Am I, are you, just a program running in some alien supercomputer?”

Such questions can no longer simply be jettisoned with the bong water: the wunderkind information physicist Stephen Wolfram recently garnered global attention for suggesting basically the same thing. Even casual psychedelic voyagers will find much that is familiar in Pinchbeck’s dispatches from the hinterlands of consciousness. But somewhere along the way, Pinchbeck loses his center — what Dale Pendell calls the “solar medicine” necessary to balance out the lunar enchantments of mercurial mind.

Pinchbeck doesn’t just take psychedelics; he converts to them. “The plants that produce visions can function — for those of us who have inherited the New World Order of barren materialism, cut off from our spiritual heritage by a spiteful culture that gives us nothing but ashes — as the talismans of recognition that awaken our minds to reality.” Many psychonauts do experience meaty insights into self and reality, and sometimes these insights even stay with them. The problem is that Pinchbeck’s sometimes proselytizing turn towards psychedelic metaphysics seems hasty and inconsidered, like a kid in the occult candy store, jumping from Kabbalah to kundalini. He wants so desperately to wake up from the nightmare of history that he overplays both the automatically transformative nature of these drugs and the spiritual vacuity of the non-sychedelic world they puncture. Too often he makes the cardinal mistake of taking the ally literally.

But I love books that roar. Pinchbeck has shown visionary courage and admirable integrity in writing nonfiction that stays true to his wildest thoughts and weirdest experiences. Given the myopic secularity of so much of New York’s intellectual life, Pinchbeck has essentially outed himself as a crazy fool. But he knows he’s doing it, and in that self-knowledge he transforms “this improbable pinchbeckian imposter, this rag doll of flesh and flapdoodle” into an impeccable warrior.

By taking responsibility for his own mind, Pinchbeck also underscores what seems to me the strongest argument he makes for taking psychedelics seriously: that “we have to grow up, become adults, and claim our own agency in the imaginal realm as well as the ‘real world’ of physical reality.” Though it sounds like shamanism, this spiritual autonomy is also a definitive political stance, one that Boon and Pendell underline in their own ways. These days, the imaginal realm of dreams and drugs, of poetic fragments and designer media, interpenetrates the world of power as never before. The inner realm is a battleground. But, as Pendell puts it, “One who has learned to face the gods directly has no fear of facing a king.”