I spent a weekend this November at the Colorado Convention Center in downtown Denver, attending the annual conference of the American Academy of Religion. The AAR is an immense and frazzling event, a professional nerdfest that also serves as a bleak and pitiless opportunity for broke postdocs and recently-minted PhDs to desperately scramble for an ever-shrinking slice of the moldering humanities pie. But I still had a lot of fun. Besides hobnobbing with pals in the tantric and esoteric zones of contemporary religious studies, I presided over an excellent exploratory session on emerging technologies devoted to the spiritual dimension of next-level virtual reality. The panel was great, and included a particularly incisive and sometimes hilarious talk by Jacob Boss about the Mandala project, a crypto-NFT-blockchain-driven “Enlightenment Simulator” that remixes New Age, libertarian, and apocalyptic QAnon memes into a most unholy digital brew, one just waiting for next-gen AI oracles to magnify into major cult. Hold on to yr furry cowboy hats!

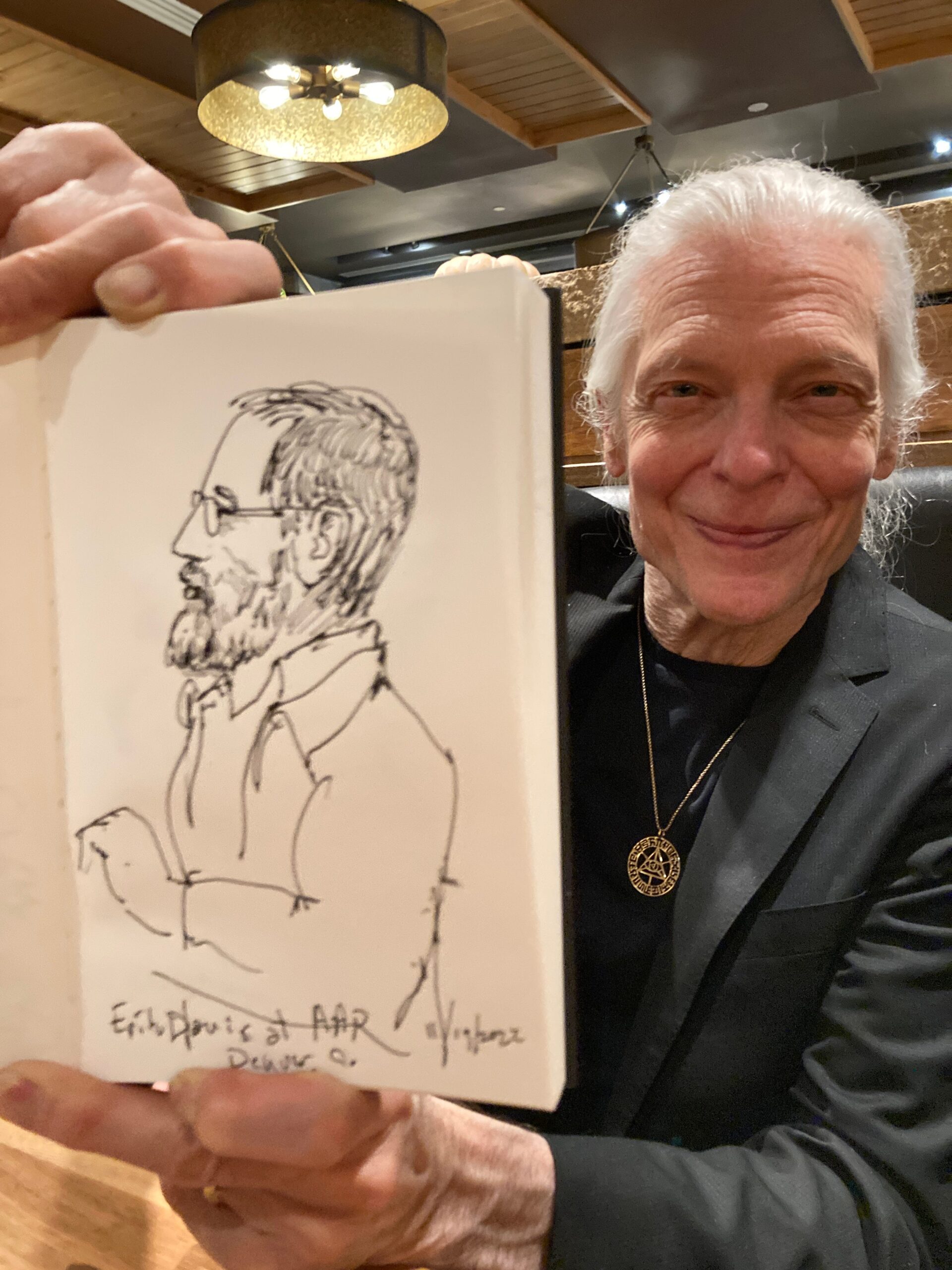

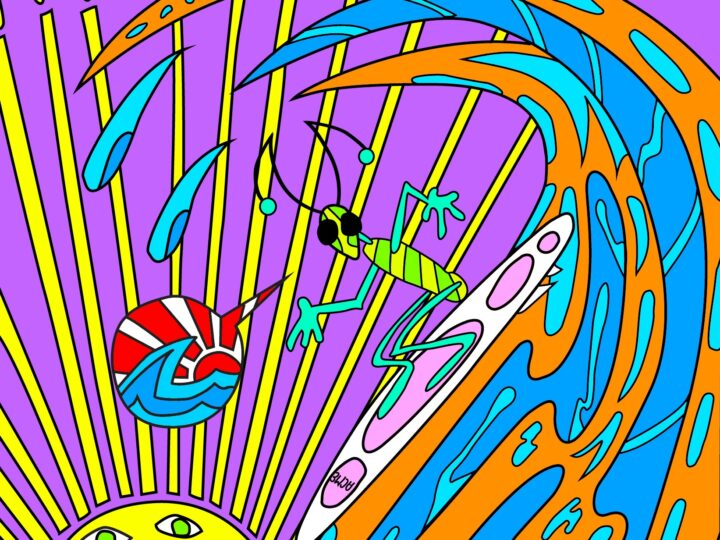

Psychedelia is finally invading the academic study of religion, something I like to think that High Weirdness helped catalyze. At the AAR I also spoke at a wonderful panel, organized by Christian Greer and Gary Laderman, that was devoted to the visionary psychedelic art of Alex and Allyson Grey, who took the unicorn by the horn and actually founded a psychedelic church called CoSM. I have been friends with the artists since I met them back in Brooklyn in the early 1990s, and have gotten to know many of Alex’s Sacred Mirrors paintings up close and personal. I coaxed them into joining the panel, where they offered a wonderful short film that covered the whole course of their fascinating career together — indeed the Greys present an exceptionally rare model of an artistic marriage whose works inspire and complement one another. Though Alex and Allyson are used to speaking to bigger crowds (with bigger wallets), I think they really appreciated the warm and serious scholarly attention they received.

When it comes to organized religion, I’m kind of like the scholar R. Laurence Moore, who once wrote that he follows faith the way some people follow baseball. For folks like us, the AAR holds a particular charm, because the event actually involves two different academic societies. One is the AAR, whose members, like me, are trained in the secular and often critical study of religion using the tools of history, anthropology, psychology, linguistics, etc. The other group is the Society for Biblical Literature, a scholarly body that overflows with theologians and other intellectuals who, while deploying many of these same tools, also possess formal religious commitments, as well as superior beards. The partnership between the two societies is a bit uneasy, but makes the event way more entertaining. Besides the cosplay factor of lots of men in robes, the exhibit hall offers spiritual flaneurs the opportunity to not only sample the latest academic critiques, but to also tour the wares that religious publishers are serving up to the intelligently believing world. So while I perused titles from the usual university houses, I also spent a lot of time at more religious outfits, from Snow Lion to St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, where I got to feed my recurring fascination with the Desert Fathers and Eastern Orthodox iconology.

I came across a lot of terrific books. These included Stephen C. Finley’s In and Out of this World, a study of UFOs and “extraterrestrial bodies” in the Nation of Islam; Brill’s Handbook of UFO Religions, which I splurged on; Ágúst Ingvar Magnússon’s clearly brilliant Gorgias Press study of Kierkegaard and Eastern Orthodoxy; a pre-print of Michael Muhammad Knight’s forthcoming Sufi Deleuze (!); and the Popular Patristics series from St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, which feature particularly boss covers. Extra amazing (and blessedly on significant conference sale) was J. H. Chajes’ monumental The Kabbalistic Tree / האילן הקבלי, a gorgeous and heavily illustrated tome that collects and analyzes hundreds of ilanot, the diagrammatic “tree of life” cosmograms that represent onto-infographics of the highest order.

Perhaps the most enchanting find though was Kim Haines-Eitzen’s Sonorous Desert: What Deep Listening Taught Early Christian Monks — and What It Can Teach Us. In this relatively brief and beautifully written volume, Haines-Eitzen interleaves a study of what McLuhan would call the “acoustic space” of early desert monasticism — whose promise of silence struggled with winds, canyon echos, beasts, and demonic noise — with the author’s own quest to both understand the yen for silence that seizes many of us today (including myself) and to record the sonic landscapes of the world’s deserts (with QR codes at the end of the chapters linking to her lovely recordings online). The volume — which I immediately mentioned to Marc Weidenbaum over at the Disquiet project — is a beautiful example of accessible scholarly writing that loops together cutting edge methods — like the application of sound studies to the history of Christianity — with personal storytelling, restrained exegeses, and touches of journalism. While I sometimes longed for a bit more speculative heft, Sonorous Desert offered the literary equivalent of a quiet, palm-fringed oasis amidst the wastelands of racket and clatter that so often characterize the modern world.

Inevitably, Haines-Eitzen tackles the question of noise, which rightly triggers suspicion. In Todd Field’s fascinating new film, Tár, we hear that Schopenhauer claimed that someone’s intelligence could be measured by their sensitivity to noise. Later, the film’s devolving central figure — who is intelligent, but also odious and narcissistic — grows psychotically sensitive to strange sounds in her apartment, which take on a hallucinatory category. But the fact that it’s hard or even problematic to define noise in the face of “music” or even “sound” doesn’t mean it’s time to abandon it as a category. For example, all wild souls understand the value of constraining anthropogenic noise, the kind of noise that forces field recordists like her to pack up the gear and head deeper into the bush. Whether it’s monks trying to escape the babble of a fallen world, or contemporary souls yearning for a sonic ecology devoid of caterwauling machine grunts, noise remains an issue however much we recognize its contingency — as Haines-Eitzen and many of the monks she reads and visits learn to do, as they develop more nuanced relationships to unpleasant and intrusive sounds.

As a city dweller, I long ago made a de facto pact with noise. But as I have aged, I have predictably grown more sensitive to the grumbles, thumps, and buzzes of traffic, furnaces, fridges, and the footfall (and pre-adolescent screams) of neighbors. These things have come to grate even as my sitting practice has helped to dissolve the very category of “interruption” and opened up my capacity for deep listening — a spacious, curious, and unreactive embrace to the world in all its sometimes cacophonous agency. But noise still bedevils.

Lately, Jennifer and I have been spending time at a place up the California coast, a tumble-down spot whose stunning proximity to the sea is paid for, acoustically, by its almost equal proximity to Highway 1. For my morning sits, I initially placed my pillow facing an interior wall which in turn parallels the road, which lies not far from the cottage on the far side of a berm festooned with redwoods. Rising very early, as is increasingly my wont, I found myself settling into the ancient white-noise pulse of waves crashing on the rocks and sand in the distance below. The cabin is tucked back on a cliff, so the surf sounds are not overwhelming, which means that individual waves are less acoustically distinct than the sets that follow a longer period.

You can probably see, or hear, what’s coming: cars, motorcycles, and especially trucks, their own frequency increasing, until by 7:00 or so, they grow more dominant than the surf. On the pillow, these noises regularly trigger squirts of irritation, resentment, and pangs of longing for things to be different than they are — a longing that, as Haines-Eitzen has shown me, itself represents a sort of whiny yen for the nonhuman sacred. Particularly distressing are the high-pitched screams that accompany the burlier bass of trucks, not to mention the farty burr of the rumble-strips that some drivers, or demons, seemingly ride for the glee of it.

Folks who live relatively near busy freeways know that thick and regular traffic can sound oceanic and relatively benign. In my case, the vehicles announce themselves individually, but initially, those appearances are literally indistinguishable from the white noise of the surf. This created a second-order problem for my irritable brain: is that distantly blooming whoosh an incoming breaker or an oncoming Sprinter? Sitting with calm attention, I have observed my brain flip-flopping as it tries to distinguish the two possibilities, and to initiate their respective affective responses. I have gotten annoyed at cars that proved to be waves, and relaxed into surf that proved to be semis. Eventually, the indeterminability of the initial noise, and the brain’s stuttering attempts to pin the tail on the donkey, grew more distracting than the traffic sounds themselves.

No question: all this is grist for the meditation mill. And I would love to say that this sonic struggle helped me overcome my reactivity, or suspend the neurotic need to categorize sounds, or to finally dissolve the ultimately contingent difference between natural and anthropogenic noise — or even the very category of “noise” itself.

Instead, I hacked the situation, and my own brain, by rotating my pillow ninety degrees. Now when I sit, the left ear is largely treated to the surf, while my right ear faces the road and its sonic hustle. I still confront the “same” sounds and the same irritations. But by untangling the stereo field and allowing the spatial orientation of my two meat-channels to automatically sift through the incoming noise, my brain now has less ambiguity to chew on. It is more willing to let go into that deeper and more delicious zone of spacious whatthefuck that swallows up the noise of the world without modulating it a decibel.

Links

I haven’t been recording podcasts with folks for some time, but I finally sat down and had an unplanned, unedited, open-ended conversation with the prolific German musician (and my sometimes guitar teacher) Markus Reuter. Markus is a master of ambient compositions and the touch guitar. I got turned on to him by a friend (and Expanding Mind guest) who met him at a prog rock summer camp. Markus studied with Fripp and often blew my mind in class with a disarming wisdom at once learned, spontaneous, elusive, and down to earth. On top of his busy music making schedule, he also does a free-form podcast he streams on YouTube.

In our chat, I started off trying to describe some peculiar shifts that meditation practice has seemingly wrought in my quotidian operating system. Throughout the day, and sometimes for extended periods, the shimmering phenomenology of the world becomes unstuck from the working assumption that these appearances are directly tied to a billiard ball universe of stuff bouncing around in real time. My resting conceptual beliefs haven’t budged much — they are weird enough as it is — but my tacit beliefs in the reality of the given seem to have loosened significantly, leaving me at brief times in a lighter and more mirror-like flux. You could describe this somewhat uncanny process as de-reification. It might be what old Husserl meant by the epoché, the “bracketing” or reduction of beliefs about what lies behind phenomenal experience, a process that he tied directly to astonishment. I am not sure I did a great job describing it here, and may even have given the wrong impression, but I hope that my riff at least has the benefit of a fresh take on an enigmatic matter.

Listening

Last April, I had the great good fortune to hear the American composer and organist Kali Malone perform with Stephen O’Malley at Frisco’s Grace Cathedral, home to a 7,466-pipe Aeolian-Skinner organ. She played music from 2019’s The Sacrificial Code, a magnificent recording I subsequently scored on vinyl so that I could make listening to it even more of a meditation than it already is. This is that rare kind of contemporary music whose alien timbres, hovering drones, and restrained dynamics demand an unfeigned contemplative embrace, at least from this audio anchorite. To listen is to both refine and soften the mind that listens. The canon-like structure of the pieces is relatively uniform: chords gently process into one another, their sustained and overtone-rich harmonies modulating methodically as they make their largely repetitive rounds through weirdly affective patterns. (I’ve found myself drifting unawares into astral litchfields, mossy fountains, far-flung dusks.) By close-miking the pipes, we are invited into the near tactile microtonal grotto of the organ, which is here stripped of the churchy reverb we usually associate with the instrument, though Malone leaves ofther sacred signifiers mildly in play. But now the sacred task is to grow intimate with stark and bristling layers of sound in which the song of musical pitch and the flutter of physical vibrations mutually invoke and clarify one another. Sacred noise.

This year Malone released a very different recording, Living Torch, which is more aggressively experimental, and more complex in both execution and effect. Malone spent two years at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, the venerable font of electronic music in Paris, where she prepared this piece for the GRM’s Acousmonium, whose dozens of articulated speakers immerse listeners into clarified soundscapes. Malone has the electro-acoustic chops to take advantage of the opportunity. Years ago she wrote a thesis on just intonation and tuning systems, which is what got her interested in organs in the first place; on Living Torch, she deploys an 11-limit system whose intervals are all based on products of the primes 2, 3, 5, 7, and 11. Xenharmonic baby! But don’t worry: the maths only pave the way for a truly multi-dimensional drifty drone zone whose nooks and crannies are carved by brass fanfares, a Boîte à Bourdons pedal machine based on the South Asian shruti box, and electronic pulses generated on the very same ARP 2500 that Éliane Radigue used to channel her Vajrayana terma tones. What results, again, is food for aesthetic intimacy: as with the similarly marvelous music of Sarah Davachi, the more you clarify and attend to your own listening, the more the pieces unfold before your very ears.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.