Edward Whittemore’s Jerusalem Quartet

Some mornings I stop and talk with Maurice, the Christian Palestinian guy who runs the local corner store. As a young man, Maurice was a rabble-rousing student living in the West Bank, but now he is a businessman worried about keeping the flowers fresh. One day I pointed to a front-page photo of Kosovar refugees, and he blurted out: “That’s what happened to my family!” Before Maurice was born, he told me, his family was forced at gunpoint from their land by Israeli soldiers. As they marched east across the earth with only a few belongings, his mother became so dehydrated she was forced to drink her daughter’s urine.

With that one absurd and humiliating detail, Maurice’s story lent a visceral, timeless depth to the suffering of refugees, Kosovar or otherwise, charging my emotions in a way that CNN’s propaganda could never match. The experience taught me that once you’ve lost faith in the simulated objectivity of the Official Story, history finds other ways to draw you into its imaginative sweep.

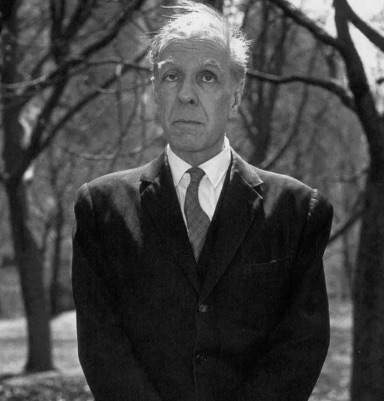

Edward Whittemore is utterly enchanted by the mystery of that sweep, a mystery whose archetypal patterns and strange surface designs are woven into the rich, goofy, and esoteric texture of his remarkable Jerusalem Quartet. The cult novels, which are linked loosely enough to be read separately but which conceal a dense, almost paranoiac web of interconnections, tell the nested tales of generations of explorers, spies, monks, junkies, and smugglers gallivanting about the Middle East from the 19th century until the 1980s. As heady as Pynchon, as droll as Vonnegut, and as entertaining as Lawrence of Arabia or Tom Robbins on a great day, the Jerusalem Quartet nonetheless fell through the cracks that separate literature, mainstream fiction, and fantasy. Though Whittemore finished up the series barely over a decade ago, the four novels–Sinai Tapestry, Jerusalem Poker, Nile Shadows, and Jericho Mosaic–are now tough to scrounge up and expensive when you do.

Orientalist fantasy hangs heavy over the Quartet, yet Whittemore does not frame his fabulations as secret peeks into the exotic and authentic Other. Instead he conjures up a polyglot comedy that simultaneously mocks imperialist, nationalist, and mystified images of the Middle East. Sinai Tapestry, for example, features a Victorian explorer named Plantagenet Strongbow, a seven-foot-tall drop-out aristocrat who discovers a comet, masters the intricacies of the Middle East, writes a 33-volume study of Levantine sex, and winds up a mystic Sufi healer with a Yemenite wife.

Whittemore’s meditations on history are serious—the most central figure in the series is Strongbow’s son Stern, an ethnically mixed gunrunner, morphine addict, and spy who spends the early decades of the 20th century pursuing his hopeless dream of a genuinely multicultural Palestine. It’s a dream that in some sense underlies the whole Quartet, with its endless interwoven tales of miscegenation, disguise, and friendship between Jews and Muslims, Arabs and black Africans, whiteys and desert dwellers. But these weighty matters often play second fiddle to Whittemore’s compulsive need to tell madcap tales about outlandish characters. The central absurdity of Jerusalem Poker is a 12-year poker match with the black market control of the Holy City on the table; the players include Cairo Martyr, an enormous African ex-slave with a masturbating monkey on his shoulder; Joe O’Sullivan Beare, an Irish patriot who arrived in Jerusalem disguised as a nun; and Munk Szondi, a Hungarian Zionist who carries a watch with three different concealed faces, all incorrect. Also in the picture is Nubar Wallenstein, a perverse Albanian nobleman who is in search of the original Bible, a mad text, “circular . . . and calmly contradictory,” originally discovered and then buried by his grandfather.

Occasionally the Jerusalem Quartet breaks down into rank silliness, and Whittemore is by no means above fart jokes, slapstick, and rather musty sex humor. But the Quartet is no cornball Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Levant. Whittemore’s colorful characters are invariably crippled within (and often without), and they wrestle fitfully with meaninglessness, time, and the grim realities of war. Sinai Tapestry ends with a portrait of the Turks’ 1922 genocidal assault on Smyrna that sobers up the reader like a jackboot at a sock-hop. As the Quartet progresses, the novels become less playful, their earlier flights of fantasy increasingly tempered by failure and pain into a resigned yet mystic melancholy. Whittemore cracks open the jewel-encrusted hideouts of fantasy, but he knows that, as one character says in Nile Shadows, “history . . . gives away your hiding place.”

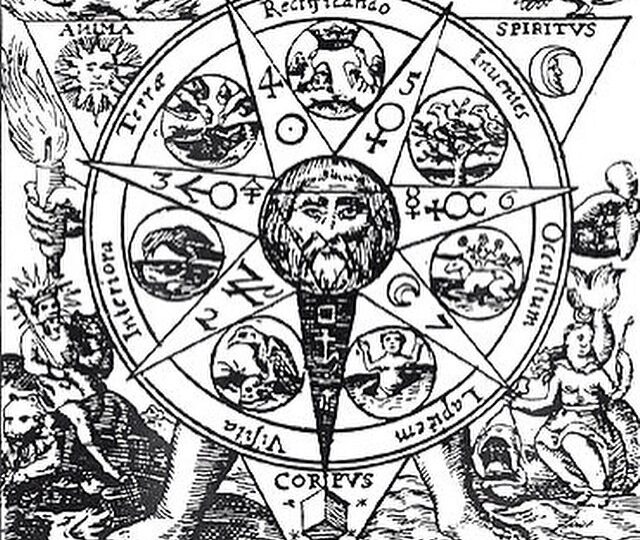

History for Whittemore is not a one-way street; it’s a psychedelic palimpsest. In Nile Shadows, which takes place in Cairo during WW II, O’Sullivan Beare drives through the Sinai toward the Monastery, an outpost of British espionage housed in the hermitage where, two volumes earlier, the elder Wallenstein discovered the original Bible. Like Shelley’s traveler in “Ozymandias,” Joe passes monumental relics in the sand: a WW I boxcar and an Assyrian chariot, Napoleonic muzzle loaders and an arch from a Roman aqueduct. The message of Shelley’s poem–that all worldly power crumbles–is offset by the surreality of this procession, which presents history less as a dry record of domination and loss than a ridiculous recurring dream.

Stylistically, Whittemore conjures up this hallucinogenic logic through synchronicities and repetitive motifs. Though the geopolitics of the Middle East always loom in the background, Whittemore is constantly probing for the gaps and loops in time. As in Gabriel Garca Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, characters return in name and shape through their progeny, while people, events, and certain phrases are regularly reintroduced, giving you the feeling that you are wandering through a labyrinth of memory.

These druggy tricks not only celebrate the hashish, nitrous oxide, and opiates that pepper the Jerusalem Quartet, but lend the text the exotic, narrative voice of, say, The Arabian Nights. In the end, though, Whittemore owes less to Scheherezade than to Jan Potocki’s 19th-century The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, another riddling and ferociously droll fantasy by a white wanderer that tucks its obsessions with sex, secrets, and Levantine lore inside a Russian doll of narratives.

As with Potocki, Whittemore’s romantic flirtations with the supernatural are ultimately held in check by a bent irony. Nonetheless, the Jerusalem Quartet is rich with homegrown theology, and leaves you with a mystic taste for the empty network of all things: “All lives are secret tapestries that swirl and sweep through the years with souls and strivings as the colors, the threads. And there may be little knots of tangled meaning everywhere beneath the surface, tying the colors and threads together, but the little knots aren’t important finally, only the sweep itself, the tapestry as a whole.”