My introduction to a new book on the most colorful of Cali cults

Using your psychic powers, mentally combine the words “cult” and “1970s,” and I guarantee that your brain will almost immediately conjure up the horror shows of the Manson Family and Jonestown, with maybe a gun-slinging Patty Hearst or a Hare Krishna flower scam thrown in for spice. These images are real, and are important to keep in mind, because small sectarian religions can be a dangerous game. But the power and persistence of these images says more about the society that keeps them alive, as a bulwark against spiritual revolt, than it does about the thousands of cults and sects and communes and subcultures that channeled the spiritual energies released by the 1960s. For most of the participants in this grand experiment in transformation, these groups were like rock bands or obsessive love affairs or even start-up companies: intense social arrangements that court creative highs and catastrophe alike, and that offered a passage through life that is, like most of our more remarkable experiences, at once damaging and illuminating.

For anti-cult crusaders and de-programmers obsessed with “brainwashing,” the Source Family could hardly present a more perfect case study. Here, amidst the wild freedom of early 70s California, was a deeply devoted group of young people, living communally, whose eccentric sexual, spiritual, and financial relationships were commanded by an enormously charismatic patriarchal figure who presented himself to his flock as both Father and God. The figure in question was also, as you might suspect, a bit of a rogue. Before changing his name to Father Yod, and then to YaHoWha, Jim Baker was a decorated Marine and judo master, and later a Hollywood restaurateur and womanizer who claimed to have robbed a couple banks to support his enterprises. (He also killed two men while defending himself, using his bare hands.) After an intense yogic conversion and a rapid assumption of mystic authority, YaHoWha led his “sons and daughters” to embrace sex and “the Sacred Herb” as ritual sacraments, to take new names, and, for a time, to break off their relationships with those friends, lovers, and family members who still lived in “the Maya.” Just to put a cherry on top of the archetype, YaHoWha not only bedded many of his female followers, but married fourteen of them, most young enough to be his daughters.

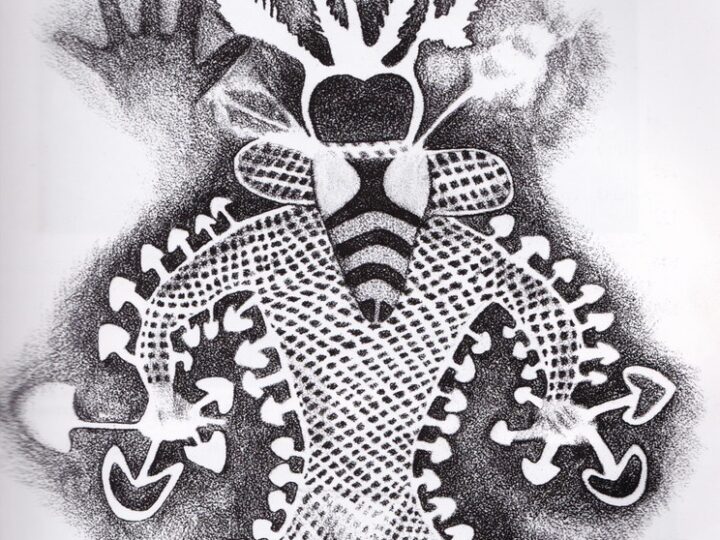

But the Source Family was also a cult in an older and deeper sense of the term. Father Yod may have been a kundalini opportunist, but he was also what the Robert Ellwood calls, in the religious scholar’s study of modern American spirituality, a magus. “Magus is neither saint, nor a savior, nor a prophet, nor a seer,” writes Ellwood. “He is a ‘Shaman-in-civilization.'” Like the shaman, the magus is part trickster, part showman, part master of initiatory ecstasies that are shared with his followers. YaHoWha was all of these, but he was no simple con man, because no simple con man would have pursued spiritual practice so avidly, nor developed such a creative New Age synthesis, nor worn such remarkable regalia, nor inspired his followers so much that today, over thirty years after their Father died, so many of them still count their time with the man to be the most remarkable period in their lives.

The Source is written by one of these happy acolytes, a woman who also became one of YaHoWha’s wives and still considers him the great love of her life. With her intelligent and intimate story, Isis helps us see the Family from the inside, however slightly, and she leaves plenty of room for readers to come to their own conclusions. She also fleshes out her text with stories from scores of other Family members, including a few who offer angry and highly critical accounts of their Father’s actions, particularly regarding sexuality.

Isis admits her own perspectives are not shared by all. But it’s clear from her writing and the other contributions that, though young, the Source Family was not a herd of mindless sheep, but a dynamic group of initiates that included many smart, creative, and ferociously loving people. These personal accounts—along with the photographs, ephemera, recipes, rituals, and recordings—makes The Source one of the most valuable resources we have about any new religious movement in the 1970s. More than that, the book forces us to look at our own prejudices—about sex and spirit, about bearded patriarchs and wide leather belts. And by coming to appreciate the creativity and exuberance of the Source Family, however tentatively or critically, we widen our view of the possible.

Here it may help to offer a few words that place the Source Family’s outlandish activities in context. For though they dressed like they had beamed down from the fleshpots of Arcturus, Father Yod and his children did not appear out of thin air. They arose, at root, from the long-standing and creative fringe of the American religious imagination, the same imagination that, in the 19th century, produced scores of mystical groups and radical communalists who also practiced polyamory and/or secret rites of visiongroups that include the Mormons and the Oneida Community, the Shakers and the Theosophists. More to the point, the Source Family arose in the bright Mediterranean air of Southern California, whose legendary traditions of visionary eccentricity, spiritual healing, and mythopoetic invention were all brought together in YaHoWha’s New Age mix.

Many Americans first moved to “paradisal” Southern California seeking health and vitality. For well over a hundred years, SoCal’s gurus and ascended master have therefore been concerned with matters of diet, exercise, and breath. The body, and its pleasures and powers, is rarely far from the spirit in California. Healthy eating was always big, and in the 1940s, a group of strapping men known as the Nature Boys established various proto-hippie ways, including a pure and sometimes raw diet. Jim Baker carried on this tradition, first by opening perhaps the first gourmet health food restaurant in the land, and then by founding the Source, the vegetarian restaurant and hipster hangout on Sunset that incubated the Family and then supported it in a flashy, Hollywood style few hippie communes could claim. The Family were committed to organic whole foods, home-birthing (and home-dying), and other features of holistic living that have become increasingly mainstream. At the same time, their green ways were saturated with Aquarian longing—the Rainbow Salad they served up at the Source used foods specifically chosen to represent all the colors of the rainbow.

YaHoWha’s mysticism was also a homegrown blend of various vibrations, a mystic syncretism that itself was characteristically Californian. Initially Jim Baker studied with LA’s Manly P. Hall, collector of the largest occult and alchemical library west of the Mississippi and author of the timeless compendium The Secret Teachings of All Ages. But Baker’s spiritual awakening came through the ministry of Yogi Bhajan, who, in 1968, brought his neo-Sikh brand of kundalini yoga to the southland, where it continues to thrive today. Baker became disciple #1, plunging into yoga’s energy fields and devoting himself to his teacher. But YaHoWha’s religious imagination started to orient itself toward the West, and he began to elaborate his own mix of Theosophical, Essene, Rosicrucian, and—who knows?even Atlantean teachings. With Yogi Bhajan, he played the perfect spiritual son. For the young people who started to attend his meditation classes at the Source, he become the perfect spiritual father, and ultimately the avatar for the dawning age.

This is where things usually go south, and in some ways they did. Rules, rituals and realities evolved and changed at lightning speed, as the group slipped ever farther from whatever “norm” still ruled in Hollywood in the early 1970s. And it is that experimental, improvised element of their mystery cult that most disturbs and fascinates. All of these people, even YaHoWha himself, were seeking and finding without a net. Spirituality was a creative act of avant-garde exploration. In this regard, cults can be like art collectives, and you will find, looking through this book, that the Source Family wove a colorful exuberance and even humor through their rituals, recipes, names, chants, and sexy Aquarian garb. It is tough to forget the image of YaHoWha in his white fedora and Rolls, or the group’s 4 a.m. cannabis meditations, or the 13-star American flag that flew over their Hollywood mansion, honoring the Freemasonic founders of America. No dour ascetics here; these folks had style.

The most well-known expression of the Source Family’s creativity ia the series of albums that the Family put out under various names on their Higher Key Records. There were some good musicians in the Family, including Sky Saxon, aka Arlick, who sang for the pivotal 60s garage band the Seeds. Another was the guitarist Djin, who shromped on all the YaHoWha records, while YaHoWha usually spearheaded the proceedings with his vox and 60-inch gong. These largely improvised albums—which range from bizarre to trite to ferociously rocking—were for a long time some of the more esoteric LPs traded among collectors of psychedelia. In the late 1990s, Saxon hooked up with the Japanese psych label Captain Trips and released God and Hair, which collects all the albums and various related sides on a set of CDs. Tons of unreleased recordings remain, some of which are included on the disc that accompanies this book.

In their self-fashioned path to illumination, The Source Family worked with the energies of their era. Cannabis was used ritually, food was healthy and holy, and psychedelic rock was forged into a cosmic glue. But sex was their most controversial vehicle of sacred transformation. Yogi Bhajan accused his former student of being “stuck in his sex chakra,” and you can see the Yogi’s point, even if the Yogi himself was not exactly on the up-and-up in such matters. It’s tough to deny the salacious and even manipulative dimension of the Source Family sexuality. Indeed, one of the most poignant statements in this book expresses one former lover’s anger at Father Yod for coercing her into the sacred bed at an impressionable age. But YaHoWha’s use of sex was not the sort of furtive fondling in the shrine room that brings down so many supposedly celibate gurus. Instead, the Family adopted an open (if deeply heterosexual) form of polyamory. Yod’s relations were not secret, and, to use the Biblical phrase, he did not generally covet his wives. For the most part, women rather than men were empowered to make decisions about sexual partners, which meant that “single sons” had to beef up their vibrations in order to get with the ladies.

The group also embraced serious neo-tantic sex ritual, which they called “Dionysm.” Besides treating sex as an expression of sacred sensuality, YaHoWha and his sons all committed to the rigorous practice of withholding their seed except for procreation or esoteric monthly rites. Restraining the typical male climax can ultimately produce intense full-body orgasms, charging the circuit between partners, but activating the kundalini is no “easy lay” in practice. Interestingly, the nineteenth-century Oneida Community, led by the bearded visionary John Humphrey Noyes, also practiced “plural marriage” and what they called “Male Continence.” The words may change, but the song remains the same.

Any religion of eros shows its mettle in the face of death. Unlike groups who deny that stark reality, the Source Family accepted death as an organic part of life. This belief was put into action when, in 1975, their spiritual father decided to try hang-gliding for the first time, crashed, and passed from this world. The Family sat with the corpse for three and a half days before calling the authorities, adopting an attitude towards home funerals that is increasingly common today. Perhaps the greatest significance of Father Yod’s death, though, was that he went out in a deeply ’70s blaze of glory, but took no one with him.

Some of the most intimate and revealing parts of The Source describe Family life following the death of their magus, as his bereft followers attempt to dip back into the “real world”or at least into those mighty waters of brainwash that most of us tread on a daily basis. Over the decades, Family members went their separate ways, some to great heights and some to terrible depths. But enough have remained in resonance with YaHoWha, the teachings, and their strange adventure together to keep the spirit of the Family’s tribal legacy alive. Feel the vibration.