Into the Mystic with Peter Lamborn Wilson

The exotic desires uncorked by travel make for a messy romance, blending recognition and projection — a crush on the Other. Muzaffarabad, Zamboanga, Babdaroon — for Westerners, can these fail to seduce? (Okay, Babdaroon is from Lord Dunsany). Unfortunately, for the last half millennium, Westerners have courted travel in empire’s brothel. Today the recognition of this imperialist imagination has led to a refreshing political deconstruction of exoticism, whether of the “primitive” or the Orient. But in some corners, this has led folks to stifle all desires for alien encounter as unworkably suspect, problematic, and dangerous…as if any manifestation of the unfettered imagination could not be suspect, problematic and dangerous.

Unconsciously echoing those who warn that the world’s dwindling diversity of plants and animals makes for a more disaster-prone biosphere, many multiculturalists want to promote or “preserve” diversity. But differences that are preserved in a jar become ethnonationalisms, whereas fruitful difference blooms on the edges, at the margins of empires, faiths, canonical rhythms. Here we find images that themselves travel, expressing their specificity while pulling the magic carpet out from under fixed identities. The question in a postcolonial culture is not how to “respect” difference, but how to embrace it, and spawn more.

For the underground anarcho-Sufi scholar Peter Lamborn Wilson, the answer lies in spiritual heresy. For over a decade beginning in the late 60s, Wilson wandered from North Africa to India to Java, but spent the bulk of his time in Iran. He explored the heterodox nooks and crannies of Islam, a religion the West caricatures as fanatically monolithic but which Wilson’s voluminous reading, Sufi practices, and face-to-face encounters with sorcerers, Satanists, and hash-smoking dervishes proved to possess one of the world’s richest and most diverse living mysticisms. Now ensconced in Manhattan, Wilson has ended his expatriot days, but he remains a cultural and intellectual nomad — a true free-thinker.

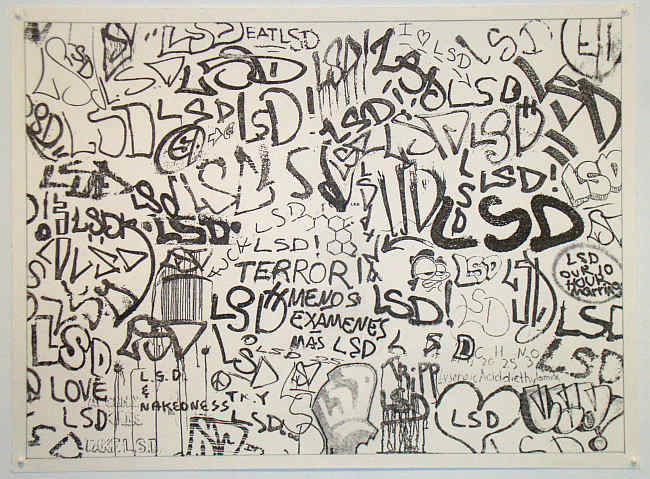

Though the bulk of his work explores the historical and mystical dimensions of Sufism and Islamic heresy, Wilson has also translated books of Persian poetry, written on angels and early American spiritual anarchism, and penned science fiction and a few pseudonymous manifestos. Every other Tuesday, his free-ranging “Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade” broadcasts on WBAI, and he lectures regularly at the New York Open Center and other local venues on topics ranging from hermeticism to Dada anthropology to dragons to “chaos linguistics” in Chung Tzu. He’s published high and low, from SF zines to Studies in Mystical Literature to Semiotext(e), which as a member of the Autonomedia collective he helps publish. And they still won’t let him into a university library in New York.

As an underground intellectual, Wilson is particularly suited to tapping the underground streams of religious history–both the truths that canonical authorities keeps hidden, and the shadows of truth that haunt history like a genie. As Wilson demonstrates, heresies most often occur far from the legislating center, and his own heretical studies have put him knee-deep in apocrypha, secret histories, occult symbols, magic pamphlets, and popular art.

These explorations not only move him from history into exoticism, but introduce a magical mode of textuality: recombinant, luminous, fragmentary. As he writes in Sacred Drift, “In the world of apocrypha the images of established religion and canonical texts acquire a kind of mutability, a tendency to drift, to reflect the subjectivities of the (often anonymous) visionaries who sift through fragments in order to produce more fragments…The world of apocrypha is a world of books made real…The apocryphal imagination turns ‘Tibet’ or ‘Egypt’ into an amulet or mantram with which to unlock an ‘other world,’ most real in books and dreams and dreams of books.”

Wilson is more than willing to navigate this no-man’s land, but unlike many fringe thinkers, revisionists and spiritual autodidacts, he never lapses into kook logic or shallow rants. For an anarchist, he has a remarkably traditional respect for rigor and cautious argument, as well as a great love for the dusty bibliographies and arcane disputes of classic scholarship. Still, he hates the academic world, and thanks God that a trickle of family money keeps him “independently poor.” This marginality grants him little status, for as he points out, “in America, the concept of an independent scholar is a null set.”

Which is a shame, not only because he’s one of the few Americans writing about Islamic culture for a popular (or at least hipster) audience, but because his essays and lectures argue for the ultimate unity of imagination and intellectual investigation. Despite all his footnotes, Wilson is ultimately less interested in historicity than what he calls “poetic facts,” insurrectionary images that puncture history. And he’s more than willing to inhale on the opium smoke of exoticism to conjure them up.

Sacred Drift picks up the thread from his earlier collection Scandal: Essays in Islamic Heresy, which remains in many ways a more scandalous book. Along with discussions of Javanese shadow-puppets and the Assassins (the heretical order led by Hassan-i Sabbah, whose dictum “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” was famously imported by William Burroughs), Scandal includes material that even today’s rather jaded audience would find heretical. Besides praising the mystical use of hashish (and including a recipe for the cannabis brew bhang), the essay “The Imaginal Game” offers a sympathetic portrayal of “sacred pedophilia,” the practice of staring at beautiful boys as a kind of “imaginal yoga.”

Sacred Drift wanders through similarly marginal territory, from Islamic Satanists to some playful Rumi translations to a profound discussion of the problems of sexuality and authority in modern Sufism. But the heart of the book is the title essay, which uncovers the “nomadosophy” of heretical Islam via Situationism, Islamic travel narratives, and the delightful figures of the flying carpet and of Kzehr, the Green Man of the Koran. The spirit of this wonderful mosaic is best summed up by a line of Rumi that precedes the essay: “Journey forth from your own self / to God’s Self–voyage without end.”

“I admit to being a romantic,” Wilson tells me as he lights up a Camel straight in his messy, funky apartment in Alphabet City. I had asked him about Said’s famous critique of Orientalism. “Romanticism is definitely part of the problem he’s identifying, and Orientalism in general does lead to fantasy. But fantasy — reveries, childhood dreams, fancies and magical images — is not entirely to be despised.” It was by becoming infatuated with such exotic fantasies that Wilson first began his relationship to Islam–which is itself a perfect anticipation of the imaginative spiritual erotics he later found in Sufi poetry, in which the mundane self is annihilated through a radical romantic infatuation with the other, the “Beloved.”

To describe his anti-colonialist embrace of the East, Wilson prefers the term “orientalismo”–an echo of the “tropicalismo” that freaked-out Brazilian intellectuals used to describe their mad cannibalism of First World culture in the late ’60s. For him, the trick is not to shackle the nomadic imagination but to refuse “gaping at cultures or trying to appropriate their spiritual sap without paying any karmic dues.” With his translations of Sufi poetry, collected in The Drunken Universe and elsewhere, Wilson gets around the problem of appropriation by co-translating with native Persian speakers.

Wilson derives his romantic image of cross-pollinating cultural exchange from the syncretisms, mutual poachings, and heretical countercultures that litters the history of religions. He points out that what he calls “fortuitous mistranslations” of one cultures often mobilize “new insurrectionary modes of cultural thought” in another. A casebook example of “heresy as cultural transfer” is Beat Zen, one of the primal inspirations for the white drop-outs who inspired the countercultural tradition that Wilson himself still very much carries on. “The first incursions of Zen into America were from Japanese of dubious orthodoxy–and I would even included D.T. Suzuki in that category. Then you had a lot of Americans who ‘didn’t understand it,’ and they made their own thing out of their fortuitous mistranslation. Something about Zen filled the bill. In terms of Japanese scholarship, they were wrong. But in terms of the spirit, it seems they were right.

“What was happening was precisely what Zen itself calls ‘beginner’s mind.’ After centuries, something radically new was happening to Zen, and unfortunately Zen was not able to appreciate it, because Zen soon moved in the Roshis. ‘Fine, fine, you’re into Zen? Here’s the real Zen.’ And the real Zen turned out to be just another fucking despotism. Even giving orthodoxy it’s due, they shouldn’t have stamped out those embers. Because it had that benefit of beginner’s mind, that sweetheart situation, Beat Zen made Buddhism what it is today: the biggest Oriental religion in America. That’s how you get things like the TV show Kung Fu. A lot of Oriental stuff seeped into that stupid show, and created a whole generation of people for whom it was part of their universe of discourse.”

For Wilson, a more important instance of “heresy as cultural transfer” occurred early this century in the work of Noble Drew Ali, the African American whose imaginative mixture of Masonry, esoteric Christianity, and his own visionary dreams of Egypt led to everything from Elijah Mohammad to hip-hop’s 5 Percent Nation. As Wilson says, “Drew Ali’s a real American prophet, the black man with a Cherokee feather stuck in his fez–the perfect image of everything I wish America were and isn’t.” In Sacred Drift, Wilson seeks the poetic fact of Noble Drew Ali, drawing not only from historical materials but from conversations with old-timers and pamphlets bought from incense-sellers in Times Square. “This is in fact the real opening of Islam in America. It’s only long after that you find middle-class white people becoming interested in Sufism.”

One of the those middle-class white persons was, of course, Peter Lamborn Wilson. He discovered the curious legacy of Drew Ali in 1964, when he met the hipsters who founded the Moorish Orthodox Church, an offshoot of Nobel Drew Ali’s original Moorish Science Temple. In 1968, reacting to “the collapse of the political into spectacle,” Wilson left America. Like many “feckless teenage hippies,” he headed for India, but eventually got booted out for overstaying his visa. Rather aimlessly, he went to the Persian consulate in Quetta, Baluchistan, where he scored a year’s visa for Iran. “After that, I was hooked.”

He discovered not only that mysticism was alive and well in Persia but that he could earn a living in Tehran just by knowing English. “It’s really still the only talent I have.” As the cultural reporter for little English-speaking newspaper, he had the freedom to explore fringe Islam as well as to meet the various avant-garde Westerns who passed through. Peter Brook gave him a job, and he almost slugged Stockhausen.

In 1974, a number of great Sufi scholars like Toshihiko Izutsu, Henry Corbin, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr, backed with money from the Shah’s wife, founded the Iranian Academy of Philosophy, an institute devoted to Sufi research. Wilson’s studies and translations continued there until the revolution. “I went to a conference in Italy with an overnight bag and never went back. It wasn’t really my fight exactly, and it tore my little world apart. Clearly in retrospect, the Shah was a violent son of a bitch who didn’t deserve to survive. But I would make an exception for Mrs. Shah. She’s a very sweet lady and I owe her a lot of fun in my life so it would be churlish to make any remarks about her.”

Both then and now, Wilson’s own romantic and insurrectionary spirit was drawn by the marginal status of Islam in America. “It’s appealing to try to speak for phenomena which are so thoroughly despised and misunderstood. Despite the fact that we have millions of Muslims in America, we still don’t have a cultural image other than the dreaded Saracen from the Song of Roland, the brown-skinned terrorist. Islam is still the enemy, and being a cultural traitor had a certain appeal to me.

“I advise everybody to travel, and that in a somewhat Sufistic sense. As the Persians say, ‘A jewel that never leaves the mind never acquires polish.’

“Of course, there’s many ways to travel. There’s tourism, there’s traveling for business, joining a scientific expedition, visiting your relatives for the holidays. There’s traveling in an army, which certainly is a very special way of moving across the face of the earth. All of these are different psychic modes.

“Travel for travel’s sake is something very special. To be free and to learn are the only goals for the pure traveler. You’ve got to be strong, and keep your psyche polished and bright and open and ready to engage. If you look on travel not just as something that’s happening to you but as something that you’re doing, it requires the spiritual will the Sufis call himmah. You have to be aware of yourself as this free-floating zone unto yourself. You can give it a spiritual interpretation if you want, but it’s incredibly real. Because it’s really you in that hotel suffering from Montezuma’s revenge. It’s not an idea of you or a simulacrum of you. It’s really your body there on the lineor at least on the toilet.”

All this recalls the work of Hakim Bey, an intimate colleague of Wilson best known for his notion of the “temporary autonomous zone.” As a surprisingly virulent concept/buzz-word, the “T.A.Z.” has spread through the computer underground to Time magazine to the hippies at Rainbow Gatherings. Bey praises Wilson’s contribution to Islam’s anarchic spirituality, and Bey should know–he served as the court poet in a small sultanate in western Pakistan until an anarchist bombing incident forced him to flee to the U.S., where he now splits his time between New Jersey and a hotel in Chinatown. Reached at his Air Stream in the Jersey wilds, Bey compares Wilson’s take on spiritual travel the “T.A.Z.”: “Part of travel is running away as well as running towards. It’s no terrible thing to run away from something if that thing is trying to destroy you, like the Empire of Work. In travel you are a kind of floating zone. You’ve got your whole little life with you in a suitcase. You become this bubble inside the cosmos running around, and you can make it autonomous or you can make it enslavement to misery depending on how much psychic energy you have.”

For Wilson, there are tricks to travel. “The people I met on the road who were really getting something out of it would be people who would settle down in Jakarta for a year and study batik. They had a love affair, and that’s the difference. The tourist’s not in love with any of this stuff.

“Another trick is to avoid places that have lost their aura by being mechanically reproduced through the medium of tourism, by 50 years of Cook tours and American Express and camera-clicking. All those things vampirically suck the life out of difference, or suck the difference out of the Other. Just going to obscure places makes a lot of sense, even if the big famous temples aren’t there. I encourage people to go to busy Third World ports and industrial cities where tourists never go because there’s nothing to see. There you often find traditional life far better preserved than the Disney World version of the exotic Orient that you’re gonna buy for a tour.”

Wilson’s reliance on the real may strike some as the kind of naivete vaporized by postmodernism. But this is a man whose gone through pomo. “Baudrillard’s a smart guy but he’s a terrible traveler. His writings on America make that very clear. He seems to see only the ironies that he expected to see.” When Wilson talks about authenticity he doesn’t mean pure unmediated experience. “It’s not at all the pure that I’m interested in. It’s the Real, and everyday life is the arena of the Real.” Wilson speaks of the Real not only as a Sufi might speak of it, but as an cultural interventionist who remains in fierce, and no doubt romantic, opposition to the spectacle. For all of postmodernism’s local truths, it remains the nihilistic metaphysics of the spectacle. “It’s only now that we’ve reached the abyss of mediation that new paths appear. Of course they were always there, and actually involve a lot of archaic models.

“Travel plays a really important role in all this. It plays the opposite role of tourism, which nonetheless exists in a strange sort of dialog with travel, which goes along with travel at the same time and sometimes seems to actually become it. Tourism is a kind of travel that deconstructs difference. The kind of travel I’m talking about is to experience difference. It’s something you do with the body–and probably ultimately the only really meaningful you do are with the body. Unlike tourism, which is the prolongation of imperialist colonialism, the kind of travel I propose is a prolongation of the heretical margin.

“Every once in a while tourists are converted into travelers. They notice that besides the image of otherness that they’re paying for there is a reality of otherness that they fall in love with. They’re attracted to it, even erotically, and they walk out the tour bus and into the world.”