Buddhism and neuroscience

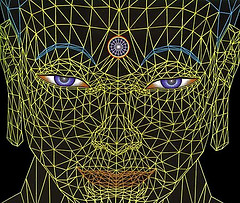

Anyone studying the mind will soon stumble across a fundamental tension between first-person and third-person accounts of cognition. On the one hand, you have three pounds of gray matter flowering on top of a post-simian spine — meat that can be mapped, poked, drugged, and registered. On the other hand, you have your own internal flow of impressions, thoughts, sensations, and memories, a stream of consciousness that includes thoughts like “the stream of consciousness is an illusion.” How can we integrate these two worlds? And is it even a good idea?

Celebrated neuro-thinkers like Daniel Dennett and Paul and Patricia Churchland are reluctant to give the “inside” of awareness or experience much explanatory weight, insisting that objective accounts of consciousness are far superior if you want to understand how the mind actually works. Such thinkers argue that subjectivity may have an undeniable intuitive appeal, but our own experience is an unreliable source of information, a morass of illusions and myths that cloud the quest to describe reality.

Yet in his 1991 book The Embodied Mind, co-written with Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch, the celebrated neuroscientist Francisco Varela insists that experience is an irreducible component of the study of the mind. “To deny the truth of our own experience in the scientific study of ourselves is not only unsatisfactory; it is to render the scientific study of ourselves without a subject matter.” Varela and crew argue that while cognitive science continues to dig into the material foundations of cognition, researchers should balance their resulting models against the “disciplined, transformative analysis” of experience itself — an analysis provided by, in their case, Buddhist meditation and philosophy. A serious student of Chogyam Trungpa, as well as the organizer of a number of formal dialogues between the Dalai Lama and Western scientists, Varela believes that Buddhism provides a sort of finely-tuned introspective tool that has been neglected in the West.

The appearance of the dharma in a work of cognitive science should not be altogether surprising. For over a century, Buddhism has been interpreted by many Westerners as a “scientific” religion, though a lot of deities and popular rituals must be swept under the carpet to make this image stick — to say nothing of the doctrine of rebirth. But the core intuition makes sense. With no belief in a Creator God or an eternal soul, the Buddha and his early followers used meditation as a kind of psychological microscope, investigating and deconstructing our deeply habitual sense that the first-person “I” truly exists. An early Buddhist work known as the Abhidharma, which reached its final form in 400 CE, chops up the comfortable shapes of ordinary consciousness into a mind-numbing catalog of mental and sensory factors that only a third-person cognitive philosopher could love.

For their part, the old yogi-scholars would probably get a kick out of the recent Zen and the Brain, a massive, 800-page tome written by the neurologist James Austin. With extraordinary intelligence and breadth of spirit, Austin explores the interaction between neurophysiology and the experiential core of Zen practice. A bench researcher rather than a cognitive theorist, Austin avoids the abstractions of brain-based philosophy and gets down to nitty-gritty detail. Summarizing an enormous amount of material on current brain science, and especially on the study of altered states of consciousness and meditation, Zen and the Brain stands on solid ground. Austin’s basic theory is that the occasional moments of insight known in Zen as kensho or satori essentially “re-boot” the brain, allowing stale and habitual structures of mind — especially those centered on “I, Me, Mine” — to dissolve and reform along suppler, more responsive, and more compassionate lines. To these ends, Austin offers a number of explicit, testable hypotheses, though he admits that studying advanced practitioners can be tough. “It might be very difficult to enter into authentic practice surrounded by all those wires, tubes, and electrodes,” says Austin, who is now retired from the University of Colorado. “Then again, for a strong adept, it shouldn’t matter.”

Along with serving up more information on the brain than most brains can possibly assimilate, Austin weaves in thoughts and experiences drawn from his own quarter century of devoted Zen practice. “We in the West come to religion from a Judeo Christian perspective, which generally means a lot of thoughts, doctrines and assumptions,” says Austin from his home in Moscow, Idaho. “The Zen approach is a little bit more like learning how to ride a bicycle, as opposed to, say, taking a coarse of astrophysics. It means getting your bottom on a cushion, learning to trust your body and to let go.” But Austin also goes against the usual grain of Zen texts by providing explicit and methodical descriptions of his own visions and mind-blowing awakenings. At once dispassionate and glittering with spirit, these discussions make Zen and the Brain a spiritual autobiography for the 21st century. As Austin himself says, “We will all be neuro-biologists to some degree in the next millennium.”

When he lectures on Zen and the brain, Austin sometimes shows slides of early statues of the Buddha. Commonly, the heads of many of these statues feature a strange protuberance, often identified as a top-knot, but which Austin sees as sign of increased brain power. “I read it as a metaphor for an expansion of faculties,” he says. “But these new capacities are no more magical than the fact that the brains of Homo sapiens are larger, more convoluted and efficient than the brains of Neanderthals. Biological brain evolution is a fact, and I hope that in another 200,000 years there will be a Homo sapiens sapiens.”

Despite the enormous accomplishment of Zen and the Brain, Austin regrets that he didn’t start his Buddhist practice earlier in his career. Christopher deCharms, a cognitive neuroscientist currently working at the Keck Center for Integrative Neuroscience at the University of California, San Francisco, was perhaps more fortunate. Having studied Asian philosophy in college, deCharms visited a Tibetan monastery in India just before entering graduate school in neuroscience. Two years into his Ph.D., he got a grant from the National Science Foundation to go to Dharamsala and study Tibetan theories of mind, a highly unorthodox move for a budding member of the brain elite. “To a person, I don’t think anyone in my department was positive about my going, and some were very negative,” says deCharms, who also practices Sri Lankan-style vipassana meditation. “It was almost over a couple of dead bodies.”

Once in Dharamsala, deCharms realized that both he and the lamas brought something valuable to the table. “I could tell them about electron micrographs of individual neural pathways and connections that were made within the brain. By the same token, they have this very rich and highly elaborated catalog of the various internal things that you can find through personal meditation.” It’s this kind of mutual illumination that convinced deCharms that such dialogues are useful, for scientists and Buddhists alike. “It’s very intellectually stimulating to test the vision of mind you are proposing, not just against extremely similar counter-proposals, but against a whole other way of thinking. It fosters whole new kinds of questions, questions that you might not have realized even were questions before.”

DeCharm’s questions — and some answers — led to a book, Two Views of Mind. A collection of interviews and rather arcane discussions concerning the science and philosophy of perception, the book goes out of its way to avoid the superficiality that poisons many cross-fertilizations of science and Eastern thought. “It’s very easy to look at the language of science and the language in some Eastern traditions and say, ‘Boy, these sound the same.’ That sells both traditions short. The meditative tradition is speaking about something that has been directly realized in the contemplative state of a yogi of some sort. That’s just plain very different than something that somebody has measured on an oscilloscope in a laboratory.”

DeCharm’s Tibetan research, coming so early in his training, transformed his attitude as a scientist, broadening his perspective on topics his colleagues continue to see through much narrower lenses. At the same time, he endured enough mockery not to bother pushing his colleagues to read his book, which was published through a Buddhist press. DeCharms chalks up some of their resistance to ingrained skepticism, and occasionally to the greater sin of arrogant ignorance. “But I think the main resistance is simply parochialism. People are very caught up in being specialists these days. If you come to them and say, ‘Hey, I have this interesting book comparing neuroscience with Tibetan Buddhism,’ they’re going to say, ‘Yeah, well there’s a two-foot high pile of articles I have to read on substance P receptors in the spinal cord.'”

There are good reasons for these folks to keep poring through their technical journals. According to Bill Press, a Zen practitioner who is pursuing a postdoc in the psychology department at Stanford, “Our knowledge base in neuroscience is not at the point where we are actually able to say many intelligent things.” Though Press studies visual processing in the human cortex, one of the most researched areas of cognition, he remains quite humble about scientific achievements to date. “Our understanding of the brain is so rudimentary that we are barely able to describe how signals are transformed from the retina to the very first stages of the visual cortex, let alone describe what’s happening during an enlightenment experience.”

As a practitioner, Press also questions whether science can make much difference on the sitting cushion. “As an intellectual puzzle, it’s kind of a cool question, how the brain relates to meditation. But I think that when you are doing this kind of practice, it’s easy to distract yourself by trying to figure everything out. In the dharma, they use the image of the finger pointing at the moon. If you want to look at the moon, you look at the moon. You don’t stare at the finger.”

Other long-time dharmaheads have a different take. Wes Nisker, the editor of the Buddhist journal Inquiring Mind and a well-known teacher of vipassana meditation, recently published a popular book called Buddha’s Nature, which integrates Darwinian and neuroscientific notions into meditation practice. “What the Buddha was really interested in was not so much cosmic consciousness but biological consciousness,” says Nisker from his Berkeley home. “He said, go in and see how your perception happens, see how your reactive mind is functioning. What the biological sciences are doing is giving great support to that practice of self-awareness and liberation. The basic truths that come out of neuroscience and biology are accessible in our own experience.”

One of Nisker’s strongest points is that an evolutionary perspective can help pry our attention away from our personal conditioning and shift it towards our conditioning as a species. “We’ve become obsessed with psychologizing in our culture. But a lot more of who we are and how we behave depends on the structure of our brain and nervous system than on how we were toilet trained.” When Nisker teaches weekend retreats, he often rolls out neuroscience lore for precisely this reason, and he’s found the tactic particularly helpful with beginners who are unmoved by the traditional Buddhist rap. “It helps people depersonalize what’s going on in their minds. Those thoughts aren’t really theirs, its just the way the mind is constructed. The mind is constructed to worry and to make sure the organism survives.”

Ultimately, the kind of mindfulness practice that Nisker teaches can lead folks to personally realize one of the core insights of Buddhism: that the self we think we are, the self we coddle and trumpet and worry about, doesn’t essentially exist. On this point, the vast majority of neuroscientists would agree, arguing that the solitary “I” is really a society of mind, or an emergent property, or an illusion fostered by some narrator module lodged in the left hemisphere. Nisker even jokingly suggests that neuroscientists set up little brain-imaging booths that would allow people to personally see the pictures of their own noodles at work. “Then we could believe it. There’s nobody home.”

In her recent book The Meme Machine, the British psychologist Susan Blackmore argues that the self is simply a complex of memes, those competitive mind viruses first described by Richard Dawkins. But at the end of her book, Blackmore suggests that we might learn to live fully and freely without the burden of a singular and illusory self anxiously holding the reigns — a suggestion rooted partly in the author’s own Zen practice. For his part, Nisker argues that Buddhism takes a step beyond science by working towards the radical transformation of our largely reactive minds. “You don’t even have to call it spiritual. It’s like this: this is what we inherit, this is the given. But here are these practices, this ancient method of examining and seeing clearly your human conditioning. When you see it clearly, you can actually increase consciousness of the whole process, and thereby find more freedom in it. That’s not only hopeful for our personal liberation, but maybe for the species as well. Maybe we’re learning how to take evolution into our own hands.”