Alan Bishop Psychs Out

Agreeing on anything these days feels about as likely as getting a total solar eclipse over your head. But I think we can all pretty much agree that something like “psychedelic music” exists, even if no one can say what the hell it actually is. Is psychedelic music made on psychedelic drugs, or music that imitates psychedelic acoustic effects, or music that sounds good on psychedelics, or music that sounds like it’s supposed to sound good on psychedelics?

If we take canonical examples of “psychedelic music” we almost immediately find ourselves in more murk. In what ways — and there are some — is Ravi Shankar “psychedelic”? What about Tiny Tim, or Unknown Mortal Orchestra, or dub, or Solange Knowles? Is a faithful cover of a Marty Robbins cowboy tune made “psychedelic” by the fact that the Grateful Dead are doing it? Are there objective features of psychedelic phenomenology — like visual trails, pareidolia, or temporal stutters — that form the basis for objective features of psychedelic music — like drones, 140-150 BPM, or endless noodling? Is there any psycho-acoustic expertise at play in the emerging ecology of drug journey playlist DJs, or is it all just feather-waving?

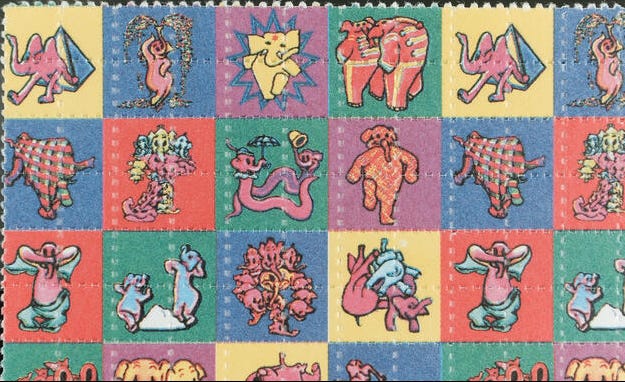

And what about music associated with specific psychedelics? Do different substances create different “sub-genres” of psychedelic music? Maybe the now antiquated term acid rock had it on the money, because a lot of old school psychedelic music was actually “LSD music.” It’s a capacious, contradictory domain, of course, roping in everything from proto-punk garage to Krautrock space-drift to noodling Phish to the very different noodles of Terry Riley. But all this LSD music is still worlds away from “peyote music”, which is essentially a body of non-electrified indigenous songs, more modern than traditional, but also tradition, sometimes passed down and changed orally and sometimes channeled anew, and accompanied by a quick heart-beat drum. Do the differences between LSD music and peyote music only reflect distinct cultural histories, or the fact that peyote grows in the soil and has been used for millennia, while LSD was cooked up with lab apparatus a couple generations ago?

By all rights, “Ayahuasca music” should be characterized by the medicine songs known as icaros, whose sometimes nasal tones seem to catalyze particular phenomenological potentials of the material. But under the pressures of globalization, icaros are giving way to all manner of heartfelt acoustic schmaltz and pan-indigenous soundtracks. “Ayahuasca” is also, it bears repeating, the traditional name for a plant preparation, while “DMT” — meaning “N,N-DMT”, and which is generally found in the brew — is a modern scientific name. Though we have archeological evidence for the use of DMT-containing plants that stretches back past 2000 BCE, “DMT music” might not have found its true groove until it started coursing through electronic circuits a few decades ago, roped to a militant psytrance beat or the more down-tempo stylings of Shpongle, whose unforgettable machine-elf mantra animates the classic track “Divine Moments of Truth.”

And what about the inevitable sub-genre “5-MeO-DMT music”? Again, while this cousin of N,N-DMT is present in trace amounts in some ancient indigenous snuffs and smoking mixtures, the name “5-MeO-DMT” reflects an abstract, more clarified kind of modern magic. The occult British band Coil instinctively recognized this when they released the track “5-Methoxy-N,N-Dimethyltryptamine: (5-MeO-DMT)” on Time Machines, a set of experimental soundtracks keyed to different mind-bending compounds that, like “Divine Moments of Truth,” also came out in 1998.

Coil no doubt had their mitts on synthetic 5-MeO, which, previous to the publication of James Oroc’s Tryptamine Palace in 2009, was a rather closely held secret among heads and underground therapists; unlike the better-known and more classically psychedelic N,N-DMT, 5-MeO-DMT was not officially scheduled, and so could largely fly under the radar. (For more on this story and what sort of protocols 5-MeO supported, please see The Toad and the Jaguar: a Field Report of Underground Research on a Visionary Medicine: Bufo alvarius and 5-methoxy-dimethyltryptamine, at once the most pragmatic and elegant book by Ralph Metzner). But what sort of music is shaped by 5-MeO, whose sublime ferocity and implacable if featureless immensity can melt space, time, and subjectivity into a cosmic white-out hurricane of Nevernow? What does that sound like? Coil honored the compound with a vast scuttling electronic space, at once insectoid and reverberant. But maybe “5-MeO music” is a perfect sine wave, or utter silence.

Or maybe a gutteral, gobbling croak. After all, 5-MeO-DMT is the dominant alkaloid found in the secretions of Bufo alvarius, the rather massive Sonoran Desert toad (the taxonomists have formally changed the genus name to Incilius, but we are sticking with the cooler Bufo ). Here we have a psychedelic that seeps from the glands of an often subterranean amphibian who crawls out of the ground during monsoons to fuck, producing an animal effluvium that had no history of psychoactive use until some white freaks read a scientific paper and took a weird-ass gamble. What does that sound like? What about toad music?

The long-hairs in the back of the class may blurt out Bufo Alvarius, the title of the 1995 debut from Bardo Pond, a highly respectable long-running psych band from Philly, who probably invoked the toad for the same reason they named their follow-up Amanita: to wear their freak flag on their fucking sleeves. And the music? A shambling, sludgy, often weed-choked middle path between Sonic Youth and Spiritualized, sometimes slight and sometimes severe and always, on this album, deeply Nineties, a path not unmarked with a certain scruffy magnificence, especially on “Capillary River” and the CD-only half-hour-long “Amen”, which breaks in all the right ways.

Mighty stuff no doubt, but Bufo Alvarius is not half as strange and timeless and haunted as the Bufo album that beat Bardo Pond to the toady punch by a single solar loop: Alvarius B.’s solo debut Alvarius B., which appeared on the Abduction label, vinyl only, in 1994.

Abduction was formed in the early 1990s to put out music by the Sun City Girls, one of the most notoriously caustic and musically adventurous bands of the American underground. A trio of mondo mystic noise-rock jazz-punk greats, the all-male Girls crawled their way out of Phoenix, Arizona in the early 1980s and never looked back. I had the great good fortune of hanging out with and interviewing the band in the mid-2000s for a feature in The Wire (well, two of ’em anyway). It was a blast. The Girls didn’t usually grant journos that sort of access, but my weirdness was my calling card, and the mutual resonance led to one of my best music profiles, whose first paragraph goes:

Alan and Rick Bishop are two halfbreed desert rats on the cusp of middle age who live in Seattle and play, when they do, in a trio called Sun City Girls. Rick’s on guitar and Alan plays bass and sings, but the brothers play with lots of other things as well: double-reed pipes, gamelon, puppets, language, demons, audience expectations, states of consciousness. The third Girl is named Charlie Gocher and he’s a scraggy Californian transplant the Bishop boys first met in the open-mic scene in Phoenix over twenty years ago. Gocher plays drums — open, slippery, consternating drums — and he writes and occasionally lets loose some mighty ornery post-Beat rants.

“Halfbreed” sounds a little harsher now that it did twenty years ago; “half-Lebanese” is more accurate. But the tone is still appropriate, because, in deep Eighties underground style, the Sun City Girls were not politically correct. They never got the memo about cultural appropriation, for one thing, and in fact lifted a good deal of their bizarro thunder from the sounds and rituals and imagery drawn from the obscure and phantasmagoric cultural byways of a planet they also humped across through all manner of adventure travels. Their devotion to world-upside-down-music eventually spawned the remarkable Sublime Frequencies record and video label, as well as some of the uncanny vibes that animate Rick’s later solo music under the monicker Sir Richard Bishop, whose astral-rambling guitar soli seemingly both pilfers and lauds the spiritual essence of a myriad Terran styles, from flamenco to dhrupad to maqam to Delta blues.

Alan Bishop’s solo project, as you might guess, is the aforementioned Alvarius B. Though Alan played bass in the Girls, he also played a mean and chaotic acoustic guitar, and recorded various ditties with a variety of cheap portable tape throughout the 1980s. Around 1992, he decided to name his solo thang Alvarius B., and started gathering the twenty-eight instrumental tracks that appeared on his debut album. This wordless music gives off few conventional signs of psychedelia, but is deeply trippy nonetheless. Call it American Feral Guitar — twangy, buzzing, slicing, biting, creepy, droning, gorgeous. Night music, desert music, culvert music. Toad music. In case there was any confusion in the matter, the first track on the album is “The Mighty Bufo.”

The exact role that psychedelics played in the post-punk undergrounds across America remains a complex and open question; some scenes embraced them while some rejected them (for more, see this discussion). But it should surprise no-one that exotica fiends like Alan and Rick Bishop were acolytes. Alan says they gobbled a lot of LSD, took mushrooms even more, and tried peyote a couple of times. Occasionally they tripped for shows, which subsequently went off the rails. Alan remembers dropping acid for one desert party out in Chino Valley about thirty minutes before hitting the stage. “It was in a yard in a middle of a valley north of Prescott, maybe fifty to seventy-five people. I remember soloing for ten minutes and then I left the stage and never came back. It was the best Sun City Girls show I had ever played up to that point. Nobody recorded it of course, it’s all up in smoke.”

The brothers heard about the toad through a friend of Rick’s girlfriend, a woman we will call K. Part of a small group of Anglo shaman heads who regularly smoked the toad, K had become a toad evangelist. This is not unusual behavior. There is something in the extraordinary depth and immediacy of 5-MeO that makes some of us want to spread the flash. (One of these days I may share tales of the initiatory cult I was intimate with in the late 1990s, known to some as the Church of the Motherfucker.) But K was having trouble finding newbies willing to roll the toad bones. Before approaching the Bishops, she had offered to turn on another pair of fraternal acid-damaged post-punk Arizona musicians, Curt and Cris Kirkwood from the almighty Meat Puppets. They declined. This set a warning flag flapping in Rick’s brain, but he and Alan accepted her offer nonetheless. They gathered at Alan’s small apartment in Tempe, and K conscientiously walked the brothers through the process, giving them a sense of what might happen. She placed a small pile of the material, which Rick compared to little flakes of crystal glue, into the pipe. Her instructions were simple. “Just take it and suck it until you drop the pipe.”

Richard went first, and the wild ride that ensued is still sharply etched in his memory. “Right off the bat there were these flashes of bright lights, almost blinding at first. Not too far after that, I was moving at an incredible speed through space. It was incredibly intense, just a tremendous speed through the universe. It was scary, at least at first. I was conscious through all of it, I was totally aware it was a God experience, that I was about to meet my maker. It became a weird kind of death trip. I thought, they are gonna find me right here, just where I am lying. But though it was a death experience, I was fine with it, even though it was scary. The constant movement wouldn’t stop, it wasn’t floaty-happy, it was boom. I was also getting some weird Native American vibe, like it was some sort of Native American experience. Later I found out otherwise. But I mean, who would have thought of drying up toad crystals and smoking them?”

Twenty minutes in, Rick was feeling much less frightened. “I knew that I wasn’t going to die.” Then Alan took his turn, and had a fine old time. “It’s its own thing,” he says now, “a completely separate type of experience compared to all the drugs I had done up to that point. It wasn’t hallucinogenic like DMT, it was more like tuning into this place, a reality that was completely separate from anything I had ever known. But I remained completely cognizant of where I was.”

In the afterglow of their trips, the Bishop boys described their experience to K, and she told them how her friends sourced the material. Out near Mount Graham, in Safford or maybe Willcox, there was a high school parking lot that hosted an immense Bufo orgy following the first big summer rains. At night, hundreds of toads came out of the muddy ground to mate, and the psychonauts would milk as much venom as they could onto plate glass to dry for later processing. Directly or not, they probably learned this extraction and preparation protocol from the pamphlet Bufo alvarius: the Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert, which had been published locally four or five years before. Pseudonymously credited to “Albert Most,” the pamphlet’s author was later identified by Vice-lord Hamilton Morris as a kindly gent named Ken Nelson, who lived in Gila, Arizona at the time and has since passed away.

Readers, please take a moment to imaginatively extract yourself from the googlebrain you partially inhabit, and reflect on what manner of furtive desert-rat networks spread this most curious lore from Most to K and her crew. Try to turn from the banalizing glare of the all-knowing screen and sniff the ambiance of arcana that must have surrounded the obscene and holy harvest at this high school parking lot back in the day in the middle of nowhere.

Rick sure was fascinated. He hunted for more toad lore through the Arizona State library, but while he found stuff about the cane toad, he could find nothing about Bufo or its venom being used in any ceremonial or indigenous context. “A few years later I found a reference in Terence McKenna. I heard about toad licking but I never knew anyone who did that.” Mostly it remained a mystery.

In the few months following his first trip, Rick did the substance a couple more times. “The other times it was interesting but it wasn’t as mind-blowing or intense. There wasn’t any revelation, and I really don’t remember the other trips. The first one was the big bang.” Given his positive, if sometimes frightening, experiences, he decided to share it with his partner at the time, who had a horrible time. “She would never talk about it. She was terrified, and came out of the experience in tears, and not tears of joy. Maybe it was her constitution, but I dunno. For me, I realized that this isn’t all fun and games, it’s not something you can just say try this, it’s fine.” After that experience, he never smoked it again, or turned anyone else on. “I didn’t want any responsibility like that. To this day I have never had that inspiration to try it again.”

The second time Alan smoked the toad, he did it on a lunch break during a work day. “I astral-projected up onto the ceiling, and watched myself re-enter, swimming back down to my body.” He tried it a few more times. Over time he started to get more of the classically hallucinogenic moments he associated with acid or mescaline, but he never met any “creatures.” Later that year, K and crew came over to celebrate Alan’s birthday, and gave him this custom-made coffee cup.

There is a difference between psychedelic experiences and psychedelic people. Not everyone who has psychedelic experiences, or wants other people to know that they have had psychedelic experiences, are psychedelic people. Alan and Rick are psychedelic people, which means they aren’t particularly interested in linking their music directly with drugs. As Alan put it, “You are always informed by your experiences.”

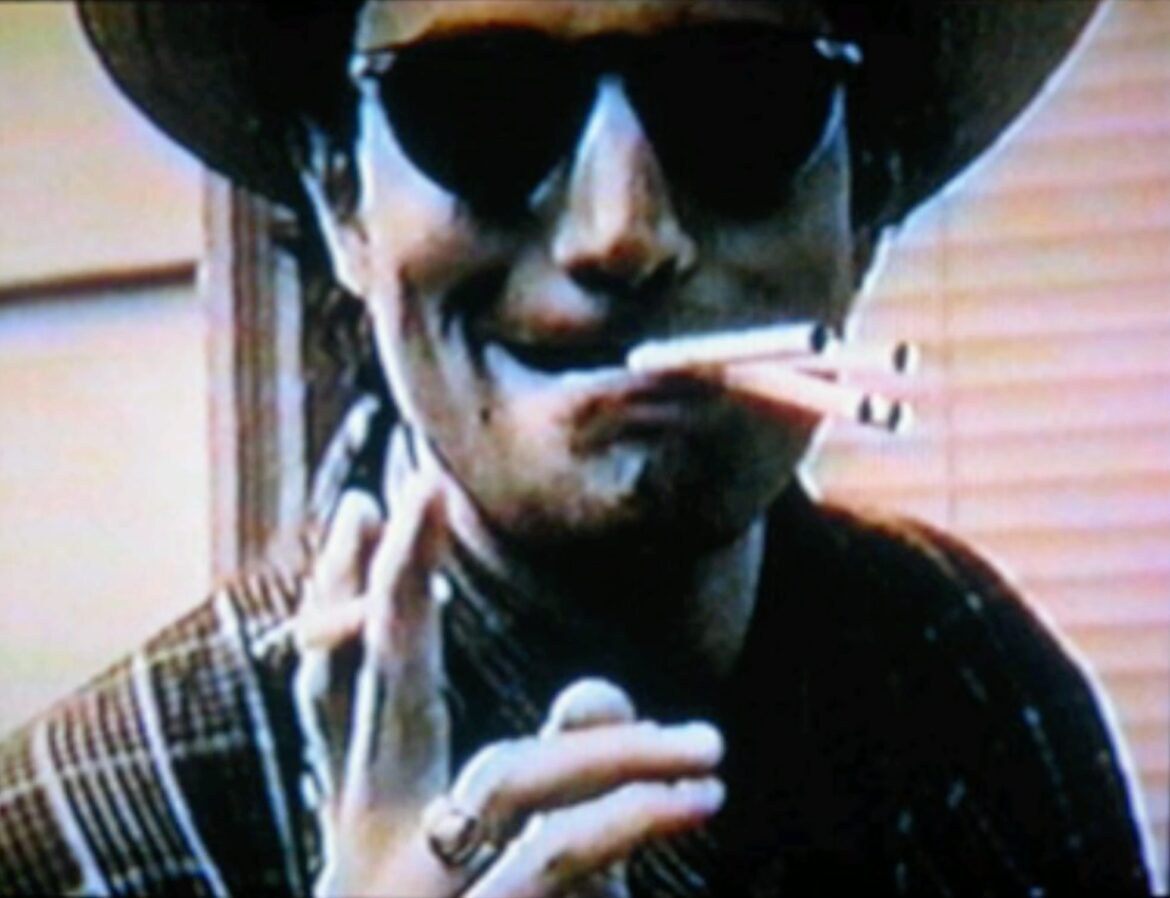

That said, it seems important to note that, while Bardo Pond may have named their album after Bufo alvarius, Alvarius B. is the name of the act, which means that Alan Bishop is performing as the toad. And most of the time, the toad has a voice, since all the Alvarius B. albums following the debut are full of songs rather than instrumentals. This voice is dark and feverish, a glittering spew of flashbacks, insults, threats, oracles, and visions, all delivered with the snarling confidence of a street-smart poète maudit.

The toad’s songcraft has changed over the years. His earlier albums present a lo-fi and jagged approach to solo guitar whose spirit is summed up in the album title What One Man Can Do with an Acoustic Guitar, Surely Another Can Do with His Hands Around the Neck of God. For a taste of this you could go back to his second album, also named Alvarius B., and check out songs like “Seeing-Eye Latte,” “Black-Eyed Boat,” “The Clear-Out,” and “Disallowed.” The tunes on his most recent studio album, 2017’s highly recommended double-CD With a Beaker on the Burner and an Otter in the Oven, are performed with a band and are largely conventional in structure — the mutant cover of Johnny Cash’s “Wanted Man” that closes the album seems of a piece with Bishop’s own masterful grasp of American song form. But that’s why Alvarius B.’s all-instrumental debut represents the authentic toad transmission. Here, even Alan Bishop — a prolific songwriter and lyrical motormouth — is rendered wordless.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though for now I will not be offering any subscriber-only content. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.