The Vanguard of Tradition

The following essay was written for the book True Visions, an Italian collection on visionary art that was edited by Massimiliano Geraci and Federica Timeto and published by Betty Books in 2006. A correspondent let me know the essay was no longer available online, so I thought I would republish it here.

I would also like to note that it is time to revisit the topic, as “Visionary Art” has changed dramatically in the decade since I wrote this essay. There are more distinct subgenres in the group, including the split between a more Europe-centered wing using “old masters” techniques and hyperrealism, versus those exploring psychedelic abstraction and more fully integrating visual lingos drawn from street art. There is also a deeper integration of artistic and material crafts like fashion accessories.

The “genre” has become far more commercialized in recent times. The field is swamped with enthusiasts and self-promoting imitators, many of whom are only tangentially aware of the artists in the ’90s and early ’00s who first developed many of the now-standard visual techniques and symbolic languages. There was always a tension in the visionary art world between “archetype” and “cliche,” and I am afraid that, though more people are creating work under that tag today, the galleries at festivals and online features a lot of material that seems stuck in a rut. But if the artistic vitality of visionary art has waned in some ways, visionary art still plays a crucial social and subcultural role in introducing people to what it means to have a psychedelic experience and to be a psychedelic person. Because they are playing an almost “religious” function of helping to shore up a worldview, it makes sense that certain themes, methods, and styles appear again and again.

Stretching out like one of the Buddha’s great bejeweled parasols, the term Visionary Art encompasses a wide variety of styles, genres, periods, and degrees of abstraction. Definitions abound, but here is my hard crystal: visionary art is art that resonates with visionary experiences, those undeniably powerful eruptions of numinous and multidimensional perception that suggest other orders of reality.

Certain individuals have a predilection for visionary experiences, but these luminous glimpses bless us all at some point in our lives, sometimes through intentionally induced trance states or psychoactive raptures, and sometimes through the gratuitous grace of deep dreams or the demented funhouse of a quasi-schizophrenic break. But we also understand visionary experience—our own and others’—through visionary art, those artifacts of human culture with its eyes agog. Such words and images and built spaces compel us to recognize that visionary experience is a constant in human life on this planet, however myriad its manifestations.

Given the rhetoric of singular seeing that underlies so much visionary art, we should perhaps not worry overmuch about boundaries and definitions. After all, such categorical thinking often has more to do with galleries and critics than with the production and reception of works of art. But pondering the category of visionary art may prove fruitful, because such considerations shape the context of our seeing—and more importantly, the way we share our seeing. Consider the related term Outsider Art, a productive if somewhat condescending category that is now thoroughly integrated into the discourse and business of collecting and critiquing art.

The very concept of outsider art emerged, paradoxically enough, inside institutions, when psychiatrists like Dr. Walter Morgenthaler began collecting the awesomely visionary paintings of psychiatric patients like Adolph Wolfli. The artist Jean Dubuffet brought such work into postwar avant-garde consciousness by amassing a tremendous and sympathetic collection of fiercely original paintings, sculptures, and drawings made in ignorance of the academy or the modernist vanguard. Dubuffet punchily dubbed this stuff l’art brut—“raw art,” a term that was reformulated in English as “outsider art”. Since becoming established as a category in the early 1970s, outsider art has brought attention to scores of remarkable creators working outside of official art circles—and, often enough, conventional reality tunnels to boot. But outsider art has in some ways become a disingenuous and highly monetized term that, for the sake of the art system it perpetuates, has eroded its very object: the outside, or at least the outside conceived as a naïve, vaguely folksy place whose creators are uncontaminated by the pedagogical strictures of western art history or the system that supports it.

From the perspective of the art system, visionary art could be seen as an attempt to broaden and extend the notion of outsider art. The American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, for example, describes its collection as “art produced by self-taught individuals, usually without formal training, whose works arise from an innate personal vision that revels foremost in the creative act itself.” That’s all fine and well, and it’s a cool museum, but this definition is deeply dissatisfying. By insisting that visionary artists are self-taught, the AVAM implies that visionary art is not found inside the schools, movements, or lineages that compose the dominant flows of art history. It becomes a purely idiosyncratic affair, reduced to the solitary, obsessive individual, a Simon Rodia or a Howard Finster. But many visionary artists are and have been formally educated. Perhaps more importantly, many self-consciously locate their work within a lineage of inspired image-makers that stretches back through generations of Surrealist dreamscapes, mystic abstractionists, and medieval iconography.

Moreover, some visionary artists emerged from or wound up within the central currents of art history. We should not forget that abstraction, the most exalted gesture of the modernist avant-garde, emerged from a lotus pond of theosophy, spiritualism, and occult meditation practices. To suggest that the visionary artist is an outsider artist is to forget that, like Redon or Kandinsky or Bill Viola today, the visionary artist also makes “insider art.”

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity

The historical lineage of visionary artists masks a deeper and more commanding claim that sets visionary art apart from the marvelous idiosyncrasies of (some) outsider art. The claim is that the visionary artist opens up personal expression to a transpersonal dimension, a cosmic plane that uncovers the nature that lies beyond naturalism, and that reveals, not an individual imagination, but a mundus imaginalis. Far from being outside, this “imaginal world” lies inside. Henry Corbin, the brilliant twentieth century scholar of Sufism, coined the term mundus imaginalis to describe the ‘alam al-mithal, the visionary realm where prophetic experience takes place. In the strict sense, it is a realm of the imagination, but a true imagination that has a claim on reality because it mediates between the sensual world and the higher abstract realms of angelic or cosmic intelligences. The mundus imaginalis is a place of encounter and transformation. “Is it possible to see without being in the place where one sees?” asks Corbin, throwing down the essential gambit of visionary experience. “Theophanic visions, mental visions, ecstatic visions in a state or dream or of waking are in themselves penetrations into the world they see.”

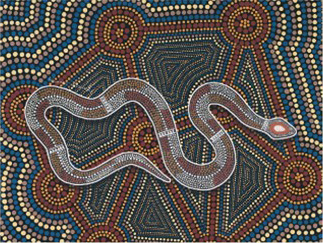

By thinking multiculturally, we might broaden Corbin’s definition to include the visionary domains that ground cultural traditions and holy paths throughout (and perhaps beyond) human history. The worlds visited by the shaman, the seer, the sibyl, and the prophet are all slices of the mundus imaginalis. Or we could just as easily say that the mundus imaginalis comes online through the labor of traditional sacred artists, who have formed and mapped the collective visions that come down to us as the various sacred maps, geometries, and pantheons of tribes and cultures the world over. By assimilating aspects of these different cultural traditions into the concept visionary art, which we cannot help but do given their similarities and our own archival perspective, the visionary domains that ground tradition appear as a single space of the transpersonal imagination, an immense vibrating network of sacred zones and populations. Thus would the mundus imaginalis become truly global.

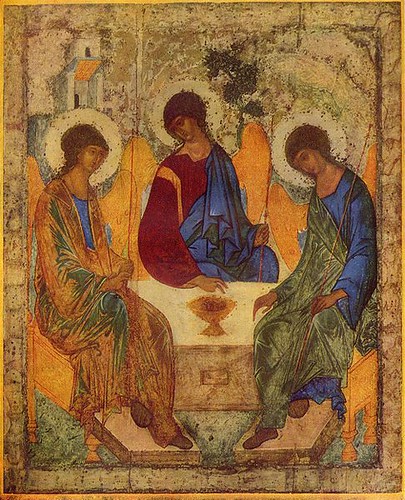

Obviously the context and meaning of “visionary art” in the premodern world is vastly different than contemporary art practices—something the more romantic proponents of contemporary visionary art sometimes forget. The “visions” captured in the premodern era are, with some exceptions (Bosch and Hildegard of Bingen come to mind), collective constructs, rendered by artists working anonymously within highly conservative cultural codes, and with little conception of “art” as we know it. Even in the individualistic West, artists were constrained by strict conventions and ecclesiastic expectations. Here the example of the Orthodox icon painter looms large: though the theology of the icon is one of the most sophisticated models of visionary art the world spirit has yet devised, the artists who crafted these contemplative portals—even geniuses like Andrei Rublev—were deeply ensconced within formal restrictions concerning color, iconography, and technique.

Andrei Rublev, The Hospitality of Abraham

Today’s visionary artist has been released from the strictures of such traditions, and must discover his own peculiar perspective on the mundus imaginalis, often drawing inspiration and insight—and sometimes cliché—from the store of traditional art. In other words, rather than rely on a specific religious or metaphysical tradition to ground and authenticate their imagery, today’s visionary artist often draws the marrow of tradition from the lineage of visionary art itself. Texts like Alex Grey’s The Mission of Art and Laurence Caruana’s vital manifesto have helped define a visionary canon through and beyond western art history. But this canon, which ties together petroglyphs, tangkas, and Salvador Dali, is more than a genealogy, because visionary art is not a purely historical form. It insists on a transpersonal, transtemporal field of resonance, a zone of imaginal connections and hidden harmonies that shape image-making outside historical time. The visionary artist invokes her own ancestors, who only demand that she discover the way anew. In this way, the power of Tradition informs untraditional art as an ever-present origin, accessible today but in some sense timeless.

The art of Ernst Fuchs, with its alchemical angels and postwar Baphomets, crackles with this sense of a transtemporal iconic lineage. Though Fuch’s Daliesque creatures and hieratic designs can be confidently traced to medieval art and surrealism alike, his dark totemic cherubs suggest a visionary event across time rather than mere allusions to earlier moments within western art history. In a more methodical and multicultural manner, Alex Grey has appropriated meridian lines, chakras, kabbalistic glyphs, and various occult body-maps from different spiritual traditions. By layering these polyglot mystic frameworks onto transparent bodies that resemble anatomy diagrams, Grey authenticates and revivifies a cross-cultural visionary body by integrating it into the contemporary visual language of objective truth: the concrete hyperrealism of medical imagery.

Ernst Fuchs, The Angel Of Death Over Purgatory

Besides plucking the resonant strings of tradition, some visionary artists also inherit the legacy of the early modern avant-garde, with its heroic quest to uncover the visual essences behind conventional forms. Far from being “outsiders”, many of today’s visionary artists are actually extending the idealism of the early modernists into the psychospiritual and explicitly cosmic direction. Meanwhile, the contemporary art world has largely declared the avant-garde project exhausted, unfit for a world of withering nihilism, intellectual gamesmanship, and coprophragic shock tactics. But in the work of Allison Grey and many other visionary artists, including the next-generation painters Kris Davidson and Vibrata Chromodoris, the mystic origins of abstraction remain a living project. Grey’s work, with its geometric density, vibrating hues, and polylinguistic codes, extends a lineage of crisp mystic abstraction that begins with Mondrian’s revolutionary but Theosophically-informed designs.

The third pillar of contemporary visionary art, besides spiritual tradition and the mystic avant-garde, is popular culture, our collective landscape of commercial dream-making. Today’s visionary artist draws from, and feeds, the “lowbrow” legacy of psychedelic poster art, comic books, skateboard stickers, concert fliers, SciFi paperback covers, and fantasy illustration. The psychedelicized popular culture that emerged from the 1960s revolutionized the social and economic context of visionary art. Suddenly, consciousness and commerce met in a mundus imaginalis open to all.

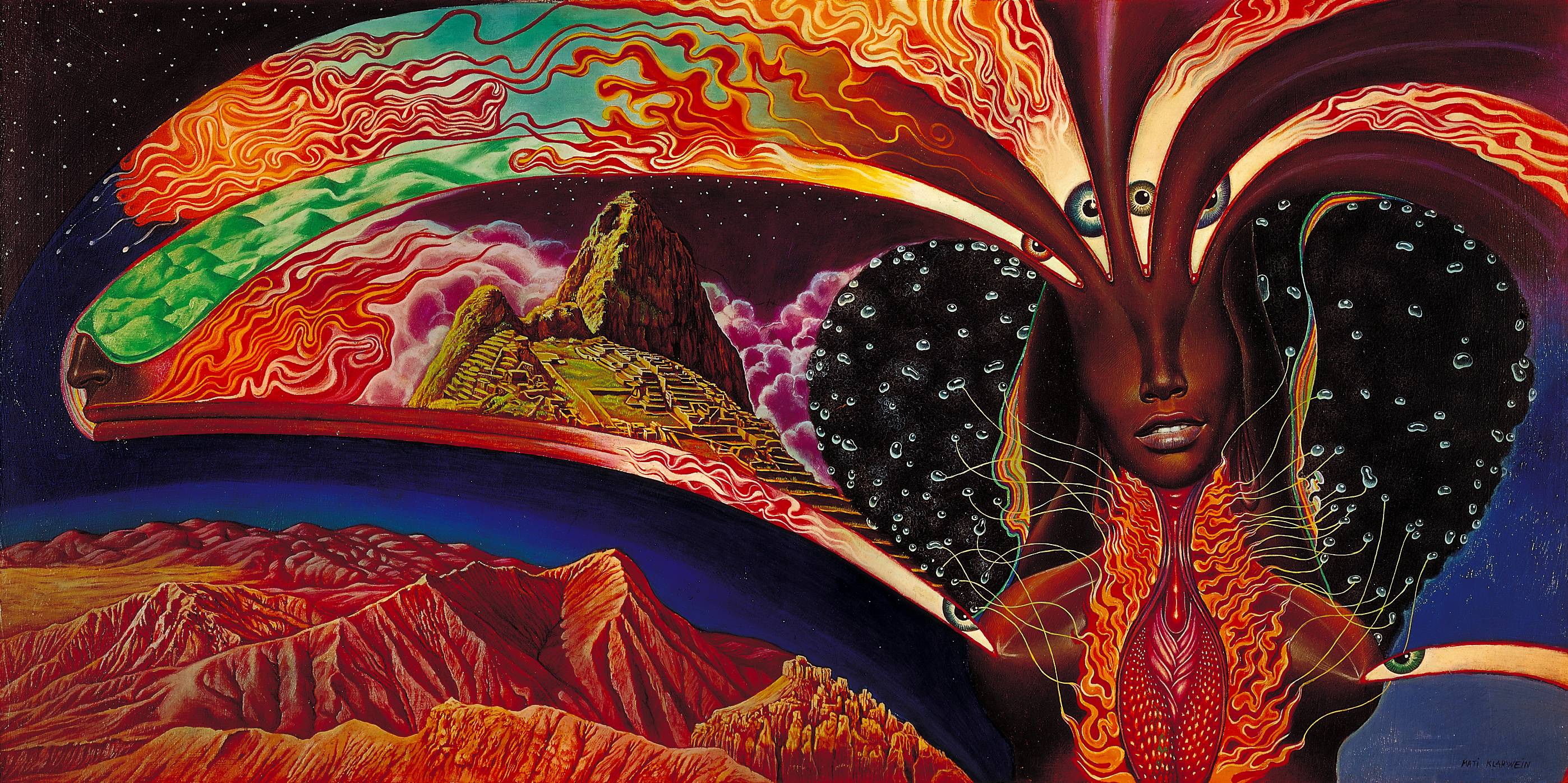

Mati Klarwein, one of the most powerful psychedelic artists of the 1960s and 70s, was best known for the album covers he designed for musical superstars like Santana and Miles Davis; Robert Venosa has also veered in and out of commercial culture, including album covers. Klarwein’s juicy patchworks of Chinese dragons, African goddesses, and Kabbalistic diagrams reflect the increasing multicultural density of the times, when global media saturation started to kick in. The mediated fragments radiating through television, magazines, film, and transistor radios resonated with psychedelic perception, which insists on superimposition and collage. Reflecting these larger shifts in consciousness, Klarwein and others begin to juxtapose and integrate iconic fragments from traditional cultures with op-art abstractions and hyperreal landscapes, creating a visionary equivalent of the sophisticated but funky musical fusions that Miles Davis explored beneath Karwein’s covers.

Mati Klarwein, Over the Rainbow

In his writings, Henry Corbin is at pains to distinguish the “authentic” mundus imaginalis from the muddier waters of the personal unconscious. Corbin wants to divide true imagination from mere fantasy, or, in more modern terms, the Jungian from the Freudian dimensions of dreamspace. But one of the most powerful and a confounding aspects of modern psychedelic culture is the erasure of such clear distinctions; instead we find ourselves in a Dionysian conflation and confounding of sacred and profane. This is particularly true in the domain of eros, which not only infuses the visionary tradition (think William Blake) but which draws together so many concerns of the visionary artist: beauty, terror, submission, animal hunger, ecstatic intensity, absurd delight. The tantric cartoons of Matteo Guarnaccia probe the profane, obsessive edges of the visionary, embracing and enjoying the lowbrow legacy even as they insist on the central mystery of sex.

Unlike Corbin, the contemporary visionary artist is rarely grounded in solid metaphysical claims based on tradition. Instead they are feeling their way through the dimensions, and they derive authenticity, when they need to, from their own experience. The most audacious claim of visionary art lies beyond genre or technique or school; it lies in the glittering possibility that artists can capture and communicate forms and traces of cosmic consciousness and otherworldly experience. The question of whether or not individual works are directly inspired by particularly visionary experiences should never dominate the discussion. But it is a vital question nonetheless, because it grounds the artifact in a living process, deepening the sense of the artist as a mediator, and the artwork as a transmission rather than an object. The work of most visionary artists deepens in light of their own visionary experiences, despite the formal transformations that occur on the way to the canvas. Despite their clear debt to Klarwein, a number of Martina Hoffman’s paintings are visionary snapshots of beings and tableaus encountered during journeys with ayahuasca and DMT.

Looking at these swirling mythopoetic gumbos, it is amazing to consider that they are, in some sense, documents. Paradoxically, the quest to capture and reflect otherworldly visionary phenomena should be considered a new naturalism. After all, whatever else they are, the phantasmagoria triggered by entheogens or REM sleep are productions of neural circuitry, the hardwiring of our human nature.

In this sense, the meaning or reality of the visions is less important than the organ that perceives them. Discussing Moses’ great theophany, Corbin writes that “the Burning Bush is only a brushwood fire if it is merely perceived by the sensory organs. In order that Moses may perceive the Burning Bush and hear the Voice calling him ‘from the right side of the valley’…an organ of trans-sensory perception is needed.” A new eye is born, a synesthetisic eye of sound and light, capable of tuning to new frequencies, of drawing patterns out of chaos and madness. This is the X-ray vision that sees through the bodies in Alex Grey paintings, or the drip-castle eye that pulls angels from the volcanic, opalescent folds of Robert Venosa’s more ambitious works. Consider Venosa’s method. He begins his paintings by laying down forms and colors like an abstract expressionist, “randomly,” the way one tosses the coins of the I Ching. Then this synchronistic field takes on a life of its own, and the nobilities that populate canvases like “Ayahuasca Dream” emerge from the globular shards like sprites from the greenery of a Victorian faery painting.

Robert Venosa, Ayahuasca Dreams

Who is to say who coaxes these entities from the abstract field—Robert Venosa, or the visions themselves, working through the artist’s eye?

As Delvin Solkinson and Eve Bradford wrote in a recent catalog, “Visionary art is evidence of a world that does not yet fully exist; a world that we are calling into being through the very act of creating and participating in the Work.” This is where the vast inheritance of the visionary tradition fuses with the intense and restless self-overcoming of the avant-garde: the imaginal world is still virtual, still ahead. At her most idealistic, the visionary artist insists on an integral connection between the work of transforming consciousness and the work of fashioning the creative artifact. For many practitioners and fans of visionary art, this doubled work restores a healing and even shamanic dimension to art, although the shamanic journeys in question may, in the case of artists like H.R. Giger, dive into the demonic.

But the most horrible demons that threaten contemporary visionary art are not slimy copulating aliens—they are the temptations of kitsch, of commercial ease, of complacent myth. To stay on the edge, to continue to incarnate the virtual, visionary art should not stray too far into mystic literalism or New Age pop. These revelations should not become icons of a new cult, the guard rails of a new paradigm. What authenticates the visionary today is the meanings that emerge through them, as they circulate through overlapping communities of perception. The solo artist as modern shaman is an old story. Today the visionary artist is less important than the visionary culture they seed, an expanding planetary network with art as one of its many nodes.