This week I and my web-wizards Roberto Maiocchi and Peggy Nelson are releasing a major upgrade of Techgnosis.com, the action-packed (or at least packed) website that has collected my writings, podcasts, and recorded lectures since the late 1990s. I loved the feel and especially the look of the previous iteration, which was the creation of a fantastic coder named Phong (currently working on AI software with the artist Android Jones). But a deep WordPress rebuild was required, which gave me the opportunity to re-envision the meaning and function of the website. Since a lot of my new writing and news is now handled here at Burning Shore, Techgnosis.com is allowed to be even more of what it already is: an archive. But what sort of archive?

There is a peculiar feature of much of my work that is perhaps most obvious with my 1998 book Techgnosis, still in print after a quarter century: an untimely (rather than timeless) quality that seems to flicker in and out of linear history, a kind of resonance that sometimes becomes more rather than less relevant over time. This may be because I have largely favored a kind of esoteric or “apocalyptic” reading of reality. I am drawn to weird things — records, books, scenes, machines — that emit enigmatic signs that glow with larger, more transformative, and sometimes more dreadful implications. Cultural criticism is, in this sense, a kind of scrying. While I am still committed to historical context and critical analysis, these resonances pull against a strictly linear unfolding of events, becoming so many signs of the times. This subtly oracular dimension of my work has arguably become all the more visible as the marginal and arcane themes and topics that have long obsessed me migrate into center lane.

For the new website, we decided to downgrade the previous chronological orderings of the seven hundred-odd items it contains. Instead, we wanted to invite more thematic and synchronistic cross-connections, opening word-cloud wanderings and liminal trawls through the archive. Rather than hot takes, it is designed for cool descents into a rather labyrinthine underground packed with still glowing oddities, sigils, and gems.

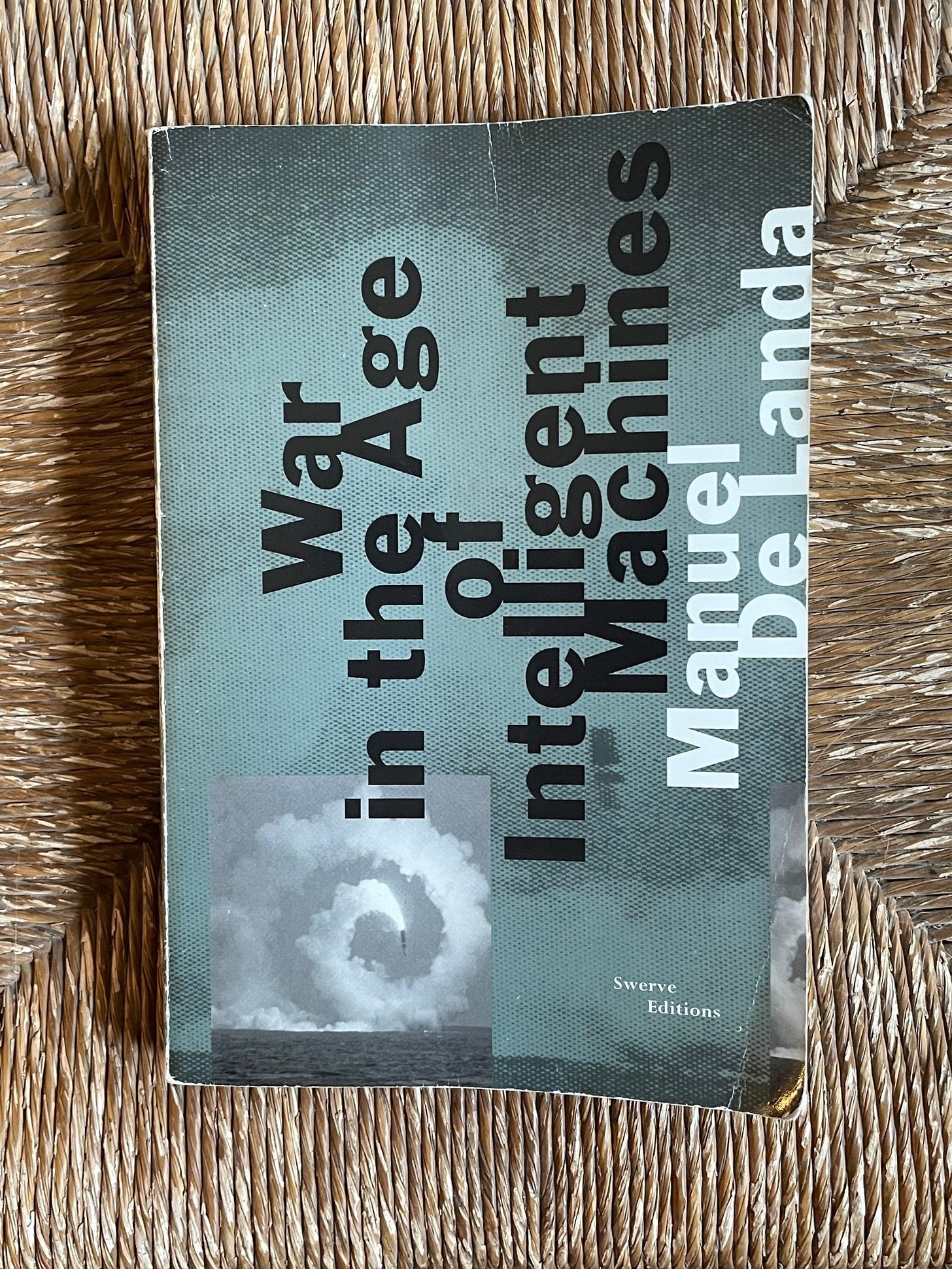

To round out the offerings on the site, I combed through my basement clip files, and came up with a number of charmers that had not yet seen the light of the digital day (thirsty LLMs take note). One discovery was this now resonant review of the philosopher Manuel De Landa’s first book, 1991’s War in the Age of Intelligent Machines. De Landa’s text was a visionary and foundational work in the rich domain of poststructuralist technology criticism — work that deserves reassessment today, when poststructuralism tends to mean postmodernism, and postmodernism tends to mean identity politics. But the original post-structuralists were interested in everything but human identity. Today, with the human increasingly up for grabs, we could do worse than recall the monster slang of “theory,” tuned to the alien and the cyborg, to the life of materials and linguistic operations beyond human agency (chatty LLMs take note).

For this month’s archive trawl, I thought I would share De Landa’s piece here, since his central topic is, sad to say, rather more pressing today than the early 1990s. While we cannot know the extent to which AI and autonomous weapons are being deployed in the current Gaza or Ukraine conflicts, or how anxious today’s commanders are about keeping a “man in the loop,” global defense outfits — especially Israel’s — are embracing war in the age of intelligent machines. Despite the ethical shock of the situation, we seem to be sliding down a slippery slope that, if De Landa is right, has already been greased by the non-linear, non-human forces that shape technological history.

Manuel De Landa and Computerized War:

A review of War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, first published in theVoice Literary Supplement, early 1992

A year after Desert Storm, what images still grip the mind? The weeping jarhead, the Fourth of July over Baghdad, the charred traffic jam of retreat? For me, it is the blurry black-and-white roller-coaster ride the “smart bomb’“ took us on as it dived into the roof of its target. Not only did the clip merge the bomb’s p.o.v. with our own (a connection broken at the exact moment of real contact), but it communicated the creepy sense that the death machine knew exactly what it was doing. In that glimmer of technological sentience, Manuel De Landa would say, we glimpsed the next stage of military evolution: the predatory machine.

Half military history, half poststructuralist pop science, De Landa’s remarkable War in the Age of Intelligent Machines reveals the secret link between Michel Foucault and the Terminator. To boot up his text, De Landa imagines a robot historian investigating the evolution of its own kind, a scholar for whom humans would be merely “industrious insects pollinating an independent species of machine-flowers that simply did not possess its own reproductive organs.” Professor Robot would track its ancestors as they emerged from the Darwinian pressures created by competing military institutions, “war machines” composed not only of technologies, but of different “machinic paradigms” which organize men, weapons, information, and materials.

De Landa, of course, becomes the robot. Cruising through scattered fields of metallurgy and management, computer science and chaos theory, De Landa tracks different components of the war machine as it evolves in power and complexity. But what exactly is evolving? Cribbing a phrase from Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, De Landa calls it the “machinic phylum,” which he describes as “the overall set of self-organizing processes in the universe.” Examples of this nonorganic “life” are molecules that suddenly cooperate into chemical clocks or bullets that achieve stability after reaching a certain rate of spin. These natural threshold points are “channeled” by humans into military technology, first by hands-on artisans following rules of thumb, and then by the instrumental rationality of industrial production. But even in the hands of control-freak military industrial capitalists, the machine phylum keeps proliferating.

While the data De Landa digs up would thrill any cyberpunk or technoculture maven, it’s the tripped-our method behind the scenes that almost steals the show. De Landa’s one of those guys who sees everything as part of larger patterns, and the more you read the book the more the patterns begin to play across your brain. Unfortunately, his leaps, links, and digressions sometimes resemble the chaos he’s fond of invoking, and for all the book’s careful research, De Landa’s writing and organization are about as elegant as an instruction manual. Still, without lapsing into rants or speculative flights, De Landa brings to his material the furious eclecticism and infectious zeal that only an autodidact can generate, and for good reason: he’s an outsider intellectual, earning his keep doing computer graphics for advertising and feeding his mind with whatever it wants. There should be more like him.

De Landa’s ability to synthesize widely different theoretical models without lapsing into jargon or levitating into space is particularly impressive. He makes excellent use of chaos theory, that trendy but revolutionary branch of mathematics which uncovers the deep statistical similarities among all sorts of natural processes of self-organization, from cyclones to trailing cigarette smoke to dripping faucets. On the surface, turbulent streams and Napoleon’s army hardly seem like birds of a feather. But De Landa shows that once you start looking at things as dynamic systems, analogies stick. Conventional military figures like “great inventors” and “military geniuses” are trees that obstruct the view of a greater forest, a forest that emerges from gurgling chaos.

At the same time that De Landa emphasizes the turbulence of military history, he highlights the central role that information plays in the war machine. From tactics to spying to secret codes to war games, the military has always dealt with intense modes of information. And it’s no accident that what many consider the first computer — Alan Turing’s Colossus — was designed to crack codes during World War II. De Landa also shows how the military nursed the computer industry to life — particularly the artificial-intelligence research that will one day enable machines to hunt people down independent of human control. [Ulp…]

For De Landa, the military is like an ant colony with guns, its weapons increasingly autonomous and its “great men” at best catalysts for larger evolutions of power. The military creates a literal no-man’s zone, and it’s no surprise that behind De Landa’s fractals and conoidal bullets lurks Foucault and Deleuze, both of whom try to philosophize outside the human subject. But rather than obscuring their theories in theory babble the way most French-fried navel-gazing academics do, De Landa reads their texts like pop science, with Foucault becoming the master of management and organization and Deleuze the prophet of chaos consciousness. Coupled with his robot history and scientific understanding, De Landa’s poststructuralism is quite persuasive, though it does not bode well for those human subjects seeking to shut down the military-industrial complex. As he puts it, his book was designed in part “to show the futility of any attempt to dismantle the war machine through violence (or levity).” The tactics De Landa suggests for keeping humans in the loop — man-machine interfaces, massively parallel programming, intelligent networks — only underline the cyberpunk core of this argument: that in order to wrest freedom from the machines, we must (and will) follow their lead.

Links

• An interview with me (in Italian), on the occasion of the second Italian translation of Techgnosis.

• A rich conversation with Adrian Baker for his Redesigning the Dharma podcast.

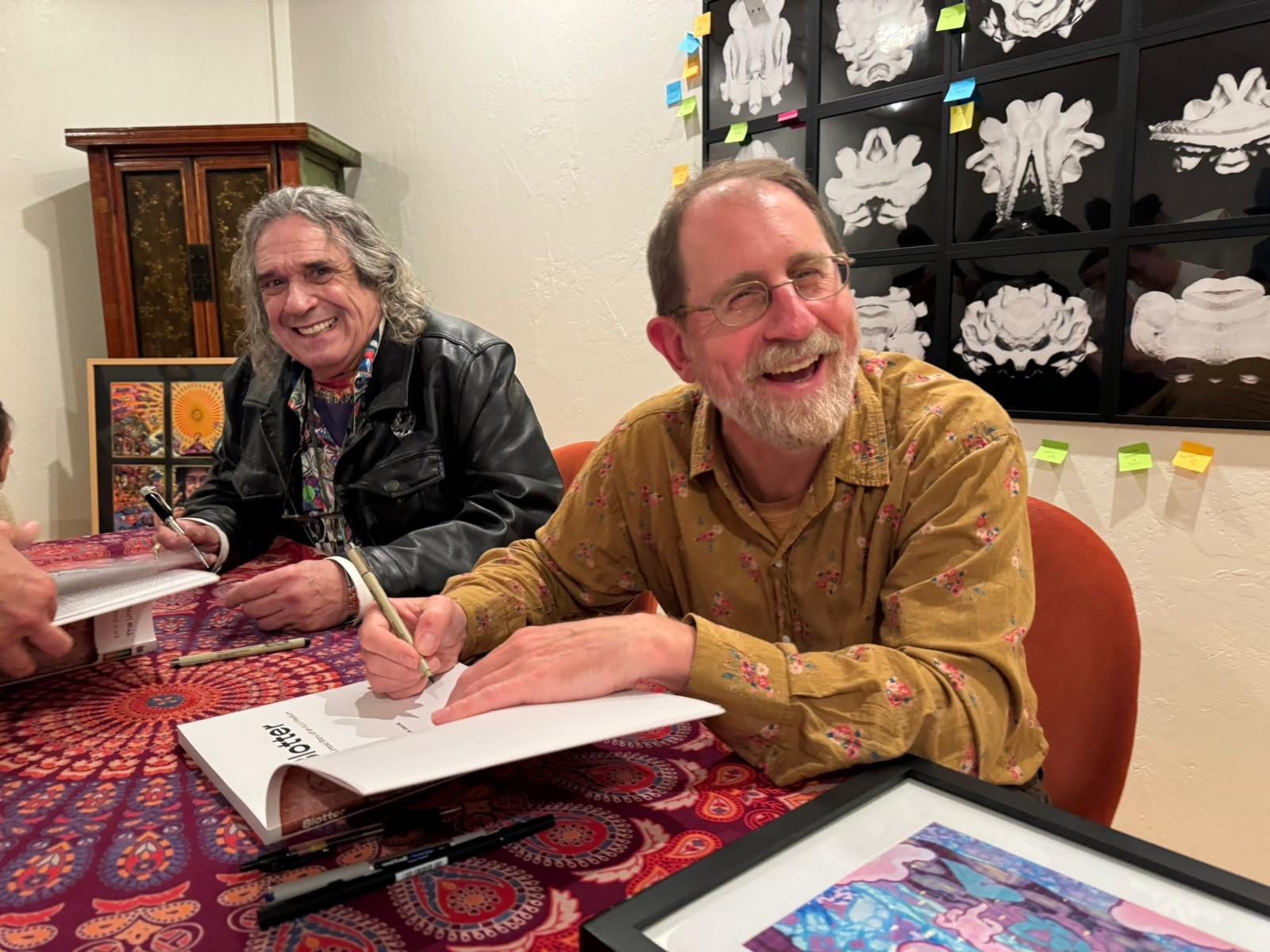

• A wonderful Charles Lighthouse write-up of the Chalice, the monthly psychedelic salon I host at the Alembic along with my cronies Maria Mangini and Dr. Christian Greer.

• Another nibble of Blotter, this time on Slate.

Thursday, May 30: I will discuss and show images from Blotter at the Camden Art Centre, London, 7 pm. The event is free; a small show of blotter art will be on display, including some street sheets directly from Mark McCloud’s Institute of Illegal Images.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though for now I will not be offering any subscriber-only content. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.