The Dzogchen and The Dead

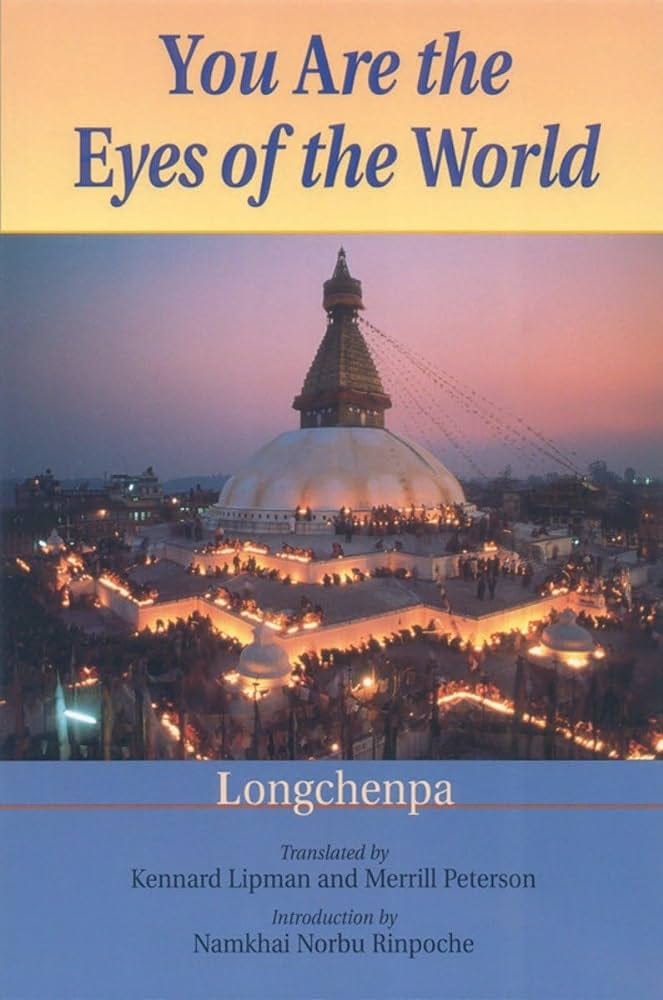

On my dusty bookshelf of dharma, nestled between Spaciousness and Self-Liberation Through Seeing with Naked Awareness, two far-out Dzogchen texts translated and annotated by two far-out Western scholar-freaks (Keith Dowman and John Reynolds, respectively), stands a slim volume by the great 14th century sage Longchenpa, who also wrote Spaciousness. Translated by Kennard Lipman and Merrill Peterson, the book is entitled You Are the Eyes of the World.

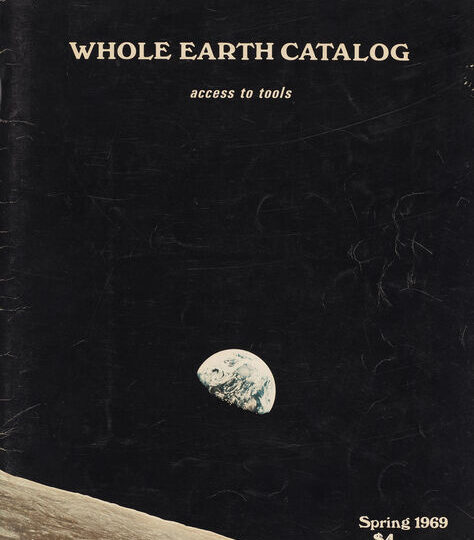

This is not the actual name of Longchenpa’s text, which Lipman and Peterson render as The Jewel Ship: A Guide to the Meaning of the Supreme Ordering Principle of the Universe, the State of Pure and Total Presence. That last part of the subtitle is a key part of Dzogchen teachings, which point towards the immediacy of our own essential (but usually obscured) state of immaculate awareness. Since the phrase “eyes of the world” does not appear in The Jewel Ship, we should assume that the translators came up with the title, and we should assume as well that at least one of them is a Deadhead, because the phrase is lifted whole from “Eyes of the World,” a Dead tune that first appeared on wax fifty years ago, on Wake of the Flood, and has since captured the hearts and minds of many a hippieshit bone-dancer, very much including myself.

Truth be told, no assumptions are necessary here, since four lines from the song’s chorus, written by the immortal Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, are fused into the epigraph for the Longchenpa book:

Wake up and find out

you are the eyes of the world

wake now, discover, that you are the song

that the mornin’ brings.

In the song, which you might as well listen to as you read this, this chorus erupts out of an endlessly unfurling tapestry that supports everything else, both the verses and the long, shimmering, playfully jazzy jams the band regularly wove from the tune’s threads. Hunter’s verses are infused with images of natural cyclicity and the suggestion of a frustrated religious search (a redeemer who fades away, a wagon—a Buddhist “vehicle”?—loaded with clay, etc.). But when the chorus hits, the slippery, minor-tinged groove that supports these enigmatic images is interrupted by a clearly marked rhythmic shift into something more confident and joyous, a sort of honky-tonk anthem. The invitation to “wake up and find out”, rooted in G, punctures the otherwise dominant Emaj7 riverrun of the tune; to use a bit of Dzogchen jargon, it cuts through.

I am not alone in believing that “Eyes” is the emerald in the Dead treasure chest, a timeless gem with all manner of glimmering facets. The shine we now face is a question of comparative religion and psychedelic insight: how did Hunter’s chorus line come to bejewel the English translation of a text by a Tibetan Nyingma master of atiyoga, the highest of all yogas?

As I discussed with Jesse Jarnow on an excellent recent episode of the Good Ol’ Grateful Deadcast devoted to “Eyes”, there are some undramatic historical reasons for this connection. (I also talk about Rick Griffin’s cover art for the album in the “Weather Report Suite” episode.) The psychedelic movement of the 1960s seeded the rapid spread and transformation of Buddhism in the West. As Kerouac demonstrated in his second published novel, the “dharma bum” was already a figure of Beat religiosity in the 1950s. But the locus classicus here is The Psychedelic Experience, a 1964 trip guidebook based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead written, or appropriated, by Tim Leary and crew (for much more on this strange book, see my scholarly article “The Psychedelic Book of the Dead.”) As the decade unfolded, acid heads as numerous as sands in the Ganges were drawn East; though initially attracted by the exotic “mysticism,” many stuck around for the philosophy, the practices, and the often extraordinary teachers. Many of these psychedelic seekers evolved into well-known Western dharma teachers and lineage holders, including Jack Kornfeld, Lama Surya Das, Joan Halifax, and Jun Po Denis Kelly, a senior Zen Roshi who also helped produce and sell Windowpane LSD back in the day. Other hippie types became scholars and translators, men and women who tucked their freak flags behind their doctoral robes.

![Wake Of The Flood (50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition) [ALAC] Wake Of The Flood (50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition) [ALAC]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F14e8bb1a-a39e-45c3-bc5e-9b3041dc553b_550x550.png)

According to Aaron Weiss, a Tibetan scholar and translator who trained at CIIS under the great Steven Goodman, a number of American Tibetan translators are Deadheads. One stand-out is Craig Preston, an inveterate long-hair who not only mentions the Grateful Dead in the acknowledgements to his textbook How to Read Classical Tibetan, but lists specific shows that inspired him. When I asked Weiss about the title of the Longchenpa translation, he also turned me onto a bit of lore about the phrase “eyes of the world.” Turns out that this image does pop up in Tibetan literature, where it appears as a folk etymology for the Sanskrit and Tibetan words for “translator.”

The Tibetan term “lotsawa” (lo tsA ba) is of uncertain origin, though often hypothesized to be a corruption of the Sanskrit term lokacakṣu, which appears to mean “eyes” (cakṣu) of the “world” (loka). Because of this, Tibetans will sometimes rephrase lotsawa as ‘jigs rten mig (“jigten mik”), “eye of the world.”

Given this, Weiss figures that the cheeky translators of You Are the Eyes of the World could be referring to their own translation, or to their teacher Namkhai Norbu—perhaps the most wizardy of recent Tibetan masters prominent in the West. Most likely though, they are referring to the reader her- or himself, “who might, through realizing the meaning of The Jewel Ship, wake up to discover that ‘he’ (i.e. his awareness, rigpa) is the light that the morning (the dawning of wisdom) brings.”

The song’s chorus is in the imperative mood: present tense, and second person. “Wake up and find out” isn’t a half-assed suggestion but a commandment, albeit a gentle one, to recognize your identity with the eyes of the world right now. In this, it sorta resembles the “pointing out” instructions that lamas use within Dzogchen—and related Mahamudra and Bon traditions—to directly introduce the “pure and total presence” of rigpa to the student. According to Dzogchen, this pure and radiant awareness is already in you, already animating your perception, like the silver screen upon which the immersive movie of your life is projected. Revelation in this view isn’t something produced or given from on high, but something you recognize as having always already been the case: you wake, now, and discover that awakening has been pervading the picture, and you, all along.

The chorus of “Eyes” belongs to a handful of deeply psychedelic gestures found in Dead songs, moments where the experience of actually listening to the tune, there on the dance floor, is prefigured and included in the words, which thereby hit your tripping brain with the force of a grok.

One of my favorite examples here is “The Wheel,” a live favorite that first appeared on Garcia’s debut solo album. The song’s lyrics, also by Hunter, can be read as a mystic meditation on the great matter of Time, that loopy slipknot of samsara and eternal return that “turn(s) by the grace of God.” But to any suitably bemused trippers in earshot, the loosely imperative mood clarifies a more immediate concern:

The wheel is turning and you can’t slow down,

You can’t let go and you can’t hold on,

You can’t go back and you can’t stand still,

If the thunder don’t get you then the lightning will.

It bears noting that lightning is one of the core Bay Area symbols of LSD, an image that goes back to the “white lightning” bolts on Rick Griffin’s 1967 Be-In poster, which inspired a famous brand of LSD made by Owsley, who also included a thirteen-point bolt in his famous Steal Your Face logo.

The psychedelic message tucked into “The Wheel” is that, while LSD can be sublime and a lot of fun, it can suck you into gnarly churning loops you can’t for the life of you break. “Won’t you try just a little bit harder / Couldn’t you try just a little bit more?” demands the song, which suggests the sort of conundrum that maybe only the music itself can remedy. After all, there is the friendly reminder embedded in “Franklin’s Tower”: “If you get confused, listen to the music play.” God knows how many dancing fools that little tip has reeled in from the brink.

When lines like these hit you, they hit like synchronicities, like messages from a hidden order of time, an order that heightens the salience of Now. “Sometimes the light’s all shining on me,” is not just a line from “Truckin’”, but an existential suggestion, one often enhanced with stage lights. The light may or may not hit you when you hear the lyric, because that “sometimes” is part of the charm, or more accurately, part of the grace—a Christian term that refers specifically to spiritual goods that God hands out because He wants to, not because of anything you have done. Grace is unasked-for, unforced, beyond all tricks and entreaties, and the word appears in many a Dead song.

Grace, named or not, is a crucial feature of psychedelic spirituality, particularly in the sort of unchurched, hedonic variety represented by Hunter and the Dead. As the band sings in “Scarlet Begonias”:

Once in a while, you get shown the light

In the strangest of places if you look at it right

Moments of grace are given freely and unpredictably, and they can pop up anywhere and anytime. In this, and in other ways, they resemble synchronicities, but as with synchronicities, you still have to notice them. And as psychonauts know—particularly those schooled in the Merry Prankster current that includes the Dead—synchronicities more or less function as psychedelic forms of grace. (Read Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test for more on this theme.)

Ann and Sasha Shulgin described another mode of psychedelic grace as a “PLUS FOUR” experience: “a state of bliss, a participation mystique, a connectedness with both the interior and exterior universes, which has come about after the ingestion of a psychedelic drug, but which is not necessarily repeatable with a subsequent ingestion of that same drug.” PLUS FOURS are outside the usual intensity scale, and they cannot be mechanically reproduced.

Another word for these sorts of mystic peaks—sometimes occasioned by psychedelics, sometimes by meditation, sometimes by grace—is the flash. In a 1977 interview with David Gans, chunks of which appear throughout Jarnow’s Deadcast episodes devoted to Wake of the Flood, Robert Hunter discusses the chorus for “Eyes of the World” specifically in terms of a “flash.”:

Haven’t you had that flash? Of looking through everyone’s eyes at once? Haven’t you ever walked down the street and inhabited everybody’s….London is a good place to do that. There are so many things going on behind those windows and the only way that you can possibly find out is to inhabit them all for a while. But you can’t be yourself when you are doing that. Everyone is there but you.

The way Hunter uses the jargon, the “flash” is a category of peak experiences that have a general, recognizable character. You know, that flash. Of his London grok, Hunter says, “That’s a flash that’s open, that people do, that’s a regular flash.” While there are some precedents for this kind of overwhelming optic multiplicity in the literature of mystical experience—I am thinking here of Krishna’s appearance to Arjuna in the 11th chapter of the Bhagavad Gita—Hunter’s vision foregrounds it as a modern, urban event. The eyes you see through are simply human eyes, eyes in and of the world, eyes whose very multitude erases the “you” that hosts and perceives them.

In his conversation with Gans, Hunter reflects further on the second person “you” that lends the “Eyes” chorus its penetrating power. What the lyric really should be, Hunter says, is “Wake up and discover I am the song [that the mornin’ sings].” Why? Maybe it’s because Hunter had the experience himself, on some London street sometime, maybe high as a kite. But the deeper reason, I suspect, is that this sort of mega-grok is an essentially first person experience—an Absolute Subjectivity that paradoxically blooms into something marvelously pluralistic. “Usually we experience the self as a unity against everything else,” Hunter explains. “There’s me and then there’s everybody and everything else. But when you take the context that ‘Eyes of the World’ is supposed to be happening in, you lose that…All these pronouns lose their sense…But I am not brave enough to say ‘I,’ I have to say ‘you.’”

Hunter’s reticence is understandable, because the language of absolute subjectivity can come off as spiritual inflation or messianic grandiosity. The same can be said of some of Longchenpa’s poetic statements in The Jewel Ship. From the nondualistic perspective of Dzogchen, all experiences, including other beings, do not and cannot exist independently from the mind to which they appear. Longchenpa writes:

All that is has me—universal creativity, pure and total presence—as its root.

How things appear is my being.

How things arise is my manifestation.

Sounds and words heard are my messages expressed in sounds and words.

We may cringe at the spiritual narcissism suggested here, especially given all the spiritual narcissists who infest the worlds of dharma and psychedelics. But, as Hunter suggests, it all depends on how deep the “I” goes. Here Longchenpa makes it clear that the “me” who is behind the phenomenal world is not the Joe Schmoe I happen to be this time around but the “pure and total presence”—the rigpa—that animates and shines through the perceptual awareness of Joe Schmoe. As in Longchenpa’s text, this wakeful presence is often figured as a jewel, but rather than being static it is creative and effulgent. Things and beings in this view do not disappear but lose the heaviness we habitually attribute to them, becoming a “play of pure experience” composed of “apparitional, spontaneously present objects” that emerge together with the experiencing “me.”

As such, Longchenpa explicitly compares the situation we find ourselves in to a lucid dream. This is an ancient and honorable metaphor, of course, as well as a complex and sometimes troubling one. Though the Buddhists insist that we should develop compassion for our fellow phantoms, the “life is a dream” mind frame does tend to undermine the substance of the beings and things around us. If the world is nothing but an apparitional play of appearances, or code in an alien’s game of SimPlanet, it is not clear what real claims the world around us—its mountains and rivers, its critters and billions of humans—holds over us.

Hunter’s earthy lyric dodges this transcendental trap. We don’t wake to discover that we are the eyes of the universe, or the eyes of a cosmic Mind, or the eyes of a dreaming god. We are not even the surreal eye immortalized by Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose famous glimpse into the American Sublime may lie behind Hunter’s lyric as surely as it lies behind Rick Griffin’s flying eyeball:

Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent Eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

For Hunter, when we truly see, we are none of those. Instead we are the eyes of the world, the very world-word that is often explicitly opposed to the spirit or God or the religious life. In the case of “Eyes,” the world partly means the earth, from the seeds that “burst into bloom and decay,” to the beaches, seasons, and evenings that belong to the “heart.” But that heart is also human, or inside humans at least, and the song also trips along through homes and gates and wagons, all those particular ways we have of walking a path or a street, wondering what lies behind all those windows.

There is no escape hatch here, no glitch in the matrix, no floating off like a balloon from Emerson’s bare ground. Instead “Eyes” embraces the diversity and funk of earthly manifestation, even with the mortality involved, gentle now like the reaper on Griffin’s cover. We find something like this affirmation in The Jewel Ship as well:

The bodies of sentient beings, their habituations, and so forth; All environments and their inhabitants, life forms, and experiences; Are the primordial state of pure and total presence.

And since that flash might strike you anywhere, then everywhere is a potential site of awakening, even the strangest and lamest and most dreadful of places. When you open the eyes of the world, it doesn’t matter where in the world you are.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. I currently don’t offer paid subscriptions, although I strongly encourage you to forward Burning Shore and to grab that free subscription because I love those slowly rising numbers regardless. Plus you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.