The joy of joysticks

Leafing through Van Burnham’s Supercade: A Visual History of the Videogame Age, 1971-1984, a coffee-table book that fetishistically catalogs the games, arcade machines, home consoles, and early computers that distracted hearts and minds from 1971 to 1984, you can be forgiven for feeling like you’ve struck a motherload of geek porn. Between the glossy screen-shots and retro gear, though, Supercade makes a crucial point: Not only did the “Golden Age” of video games kick-start an entertainment industry that now rivals Hollywood, but it got millions hooked on the interactive screen, opening the domicile to digital circuitry and helping to transform the computer from a number cruncher into an image machine of major cultural import.

Though a distant ancestor of Pong appeared on a 5″ oscilloscope screen in the late 1950s, the first important game was Spacewar!, a product of MIT’s early hacker culture. In his essay on the game’s origins–a jewel of hacker prose as resplendent as the legendary Cap’n Crunch sequence in Neal Stephenson’s novel Cryptonomicon –Spacewar! cocreator J.M. Graetz tips his hat to E.E. “Doc” Smith and Toho monster flicks. Discussing the hyperspace button that allowed Spacewar! ships a last-ditch escape, Graetz noted that the device “introduce[d] something very like magic into an otherwise rational universe.”

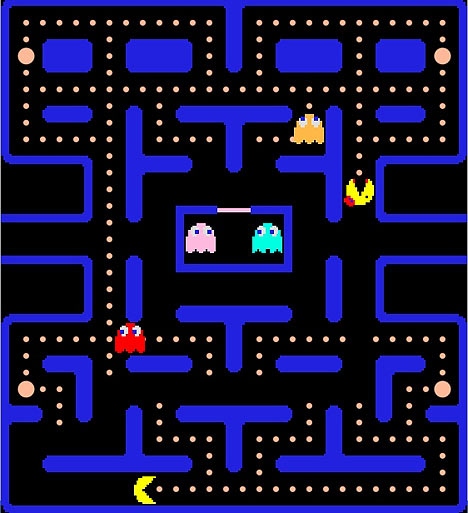

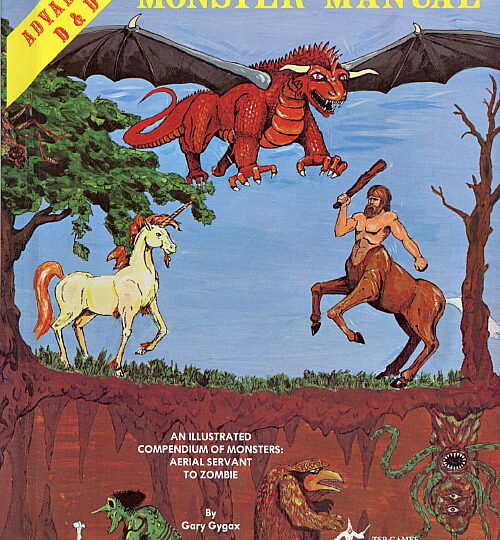

The same could be said of many of the games catalogued by Burnham, an “interactive entertainment” maven and videogame collector. The Golden Age arcade was a dark cavern of hieroglyphs, a Cabaret Voltaire of the adolescent id. For all the realism implied by games like Track & Field, Basketball, and Battlezone (which earned Atari a commission from the Army), old school video games made their mark with a kind of digital dada: bouncing strawberries, huge coins, and cute Japanese monsters. Here buzzard-mounted knights hatch from golden eggs, killer bees pursue skateboard rats, and the evil Wizard of Wor taunts players with the threat, “If you destroy my babies, I’ll pop you in the oven.”

For folks of my generation, sandwiched between hippies and Gameboy mutants, Supercade drips with nostalgia. I cannot deny the serotonin boost provided by a glimpse of Dig Dug’s begoggled character Pookah, or Burnham’s description of bare-footed stoners grooving to Black Sabbath as they assembled the first Pong games in a rented Southern California roller-rink. It’s true that not everyone will be moved by Atari logos, Activision patches, or grainy shots of Odyssey2 game consoles that belong on Space:1999. But Burnham’s archeology is both splashy and exhaustive, and students of modern visual culture or ’70s design have no business passing it up-the ad shot of four mutton-chopped hipsters playing Quadrapong in 1974 is worth the price of admission alone.

When it comes to her sociocultural axe, however, Burnham is pretty light on the grind, content to point out that video games shuttled us from an analog to a digital world. Wisely, Burnham rounds out her entries with essays by folks like Julian Dibbell, Steven Johnson, and the genius behind Q*bert. But the prize goes to Tom Vanderbilt’s homage to Asteroids, the first great vector-graphics game. Noting that its look was less Pop Art than Bauhaus, Vanderbilt writes that the game “melded Eastern metaphysics with a kind of Sisyphian struggle,” lending an almost “spiritual sense of purpose to breaking the rocks down into smaller and smaller rocks, and then into nothingness.”

With its simple lines, Asteroids embodies one of the most compelling formal tensions in these early computer graphics: the tug between cartoonish representation and chilly abstraction. Both poles were

rooted in hardware limitations, and the clever economy that programmers and designers brought to their 4k nuggets of code account for much of the charm of these games–especially in today’s era of bloatware and hyperreal graphic engines. But the element of abstraction was also a little creepy. Designed by Dave Theurer, who also concocted the “simple, yet disturbingly nihilistic” game Missile Command, Atari’s almighty Tempest employed color XY graphics to depict a series of geometric wormholes infested with minimalist monsters, which you — a crab-like polygon — had to shoot before you were sucked through hyperspace into the next screen. If Asteroids was Zen, Tempest was chaos magic.

Games like Tempest made formal gestures towards the abstract dimension that lay beyond the pixels–not cyberspace, but the stranger and more important space of algorithms, those recipes and routines that make up the basic metabolism of digital life. Indeed, the mastery of particular video games largely involves internalizing your own algorithmic responses. In order to beat the machine, in other words, you have to mimic its ways, a pleasure not without its embarrassments. As Suck.com’s co-founder Carl Steadman points out in his riff on Rip Off, the narrative frames of most video games attempt to “bury the masturbatory repetitions of hand on joystick within a false hermeneutic.”

Although a surprisingly large number of early video games involve oral consumption, the basic hermeneutic, of course, is violence: shooting and killing, search and destroy, one-on-one combat. Death Race, a vehicular hit-and-run game against pedestrian gremlins, was already getting parents and advocacy groups up in arms in 1976. But without the bubbling gore and fight-or-flight realism of today’s games, the real war here is technological, as rival console systems and arcade machines waged an arms race of hackery and hardware. In his piece on Intellivision, Steven Johnson argues that the 1979 Mattel console system was the first to sell itself based on technical superiority rather than content alone. To this end, Mattel recruited George Plimpton, thereby beginning “the short-lived tradition of hiring boozy literati to promote Donkey Kong ports.”

What Intellivision really did was initiate consumers into the cult of technical prowess that paved the way for the PC boom. Indeed, it’s no accident that Burnham ends her survey in 1984, when Apple released the Mac–a cute machine with a graphic user interface that owed more than a little to its creators’ love of video games (Jobs was Atari employee #40, Woz a master of Gran Trak 10). In other words, computers generated the momentum to conquer the world not only by spiffing up our spreadsheets, but by pleasuring us with blue ghosts, spaceships, and twisty little passages. The irony is that, as the glorious cavalcade of Supercade proves, greater machines have nothing to do with making greater games.