Golden Goa’s Trance Dance Transmission

In the early 1990s, I became aware of the growing psychedelic undertow of dance and electronic music. With the exception of the Bay Area, the United States was largely out of step with this aspect of the techno scene, and it was only through stray clues — a boast by a British backpacker, liner notes on an import ambient CD — that I first heard about Goa. When I interviewed Orbital for Spin, Paul Hartnoll confirmed the rumors: on the west coast of India, in the ex-Portuguese state of Goa, an old hippie haven hosted raves every winter, massive techno freak-outs that were less parties than rites of passage. These parties rode the cutting edge of psychedelic techno music — what we now call psy-trance — and they attracted New Age traveler types as well as the raver elite. Some suggested that Goa was the true source of raves, or at least of their spiritual essence, that ineffable gnostic intoxication whose articulation usually leaves outsiders in the dark.

Techno historians already know that English working-class kids brought raves back from Ibiza, the cheap vacation island off of Spain whose weather, slack, and lack of extradition treaties made it a Goa-style hippie colony decades ago. The original Ibizan DJs were certainly freaks, mixing Tangerine Dream in with their disco. But the holders of bohemian lore will tell you that the esoteric lineage of electronic trance dance lay further east, in Goa. When I spoke to Genesis P. Orridge, the leader of the magickal techno/industrial outfit Psychic TV, he said that “the music from Ibiza was more horny disco, while Goa was more psychedelic and tribal. In Goa, the music was the facilitator of devotional experience. It was just functional, just to make that other state happen.”

Contemporary attempts to characterize underground dance culture’s experience of this “state” often have recourse to the French philosophers Deleuze and Guattari, whose writings have helped us wrestle with nonordinary states of consciousness and perception without recourse to either religious or reductivist languages. The notion of a plateau, derived from cybernetic philosopher Gregory Bateson’s studies of Balinese aesthetics, helps characterize a state of becoming which is realized without climax or resolution. Similarly, the famous “body-without-organs,” a phrase cribbed from Artaud, can be said to describe an immanent and literally dis-organized field of animate matter, at once a pure virtuality and a synthetic bundle of molecular affects.

Though Deleuze and Guattari take great pains to avoid the slightest taint of the transcendent, the body-without-organs, or BwO, veers ineluctably towards sacred forces. In “How to Build a Body without Organs,” the authors explore the term in the context of drugs and somatic spiritual praxis. There is mention of Taoist arts, of Artaud’s peyote experiences in Mexico, of a Castaneda-like “egg.” The most important parallel, however, is one that they do not explicitly draw, and that is between the BwO and Hindu tantra. Loosely speaking, tantra aims, not to suppress or transcend the emotional and physical energies of the body, but to embrace and transmute those energies through a kind of internalized, psycho-ritual alchemy. Over and against study and reflection, tantra emphasizes procedures: mantra, visualization, hatha yoga, ritual, all geared toward the transmutation of a fundamental cosmic energy called shakti. A serpentine stores of this stuff, known as Kundalini, lies coiled at the base of the spine. This energy, which some claim is artificially stimulated by certain drugs, can be coaxed up the various etheric centers — or chakras — that lie along the central channel of the spine.

As metaphor and sometimes as practice, sexuality is key to this process, and the most paradigmatic tantric sexual procedure is the retention of orgasm in the male, an ascesis which helps sublimate sexual energy into rarer and more potent elixirs.

I apologize for this almost offensively oversimplified account, though at least it gives a taste of how these notions circulate within the popular discourse of bohemian spirituality. At the moment, though, I want us to hear the tantric echoes in Deleuze and Guattari, echoes that in turn will help us understand the alchemical dynamics of the rave. Here is Deleuze himself on courtly love:

Now, it is well known that courtly love implies tests which postpone pleasure, or at least postpone the ending of coitus. This is certainly not a method of deprivation. It is the constitution of a field of immanence, where desire constructs its own plane and lacks nothing… Courtly love has two enemies which merge into one: a religious transcendence of lack and a hedonistic interruption which introduces pleasure as discharge. It is the immanent process of desire which fills itself up, the continuum of intensities, the combination of fluxes, which replace both the law-authority and the pleasure-interruption…Ascesis, why not? Ascesis has always been the condition of desire, not its disciplining or prohibition.

The process whereby desire “constructs its own plane and lacks nothing” is intimately allied with the emergence of the BwO. And if one replaces the term “desire” with “energy” or “shakti,” one can sense the continuity of this construction with tantric procedures, procedures which, on an admittedly simplified and ad-hoc level, inform both Goan trance parties and the “spiritual hedonism” of the freak subculture that gave them their shape.

I want to make one more initial point. Despite the anti-authoritarianism shared by Deleuzians and underground ravers alike, it is crucial to emphasize that the BwO is, in many cases, a product of tradition. Perhaps better characterized as transmission, tradition is a consistent feature of spiritual claims: even the most anarchic and disruptive spiritual dynamics are often couched in terms of teachers, sacred texts, and initiations. This is certainly the case for the Taoists and the Tarahumaras that Artaud met, for the Sufi masters who inspired the tradition of courtly love, and even for Castaneda’s simulated studies in sorcery. As much as it is constructed, the BwO is transmitted. Apocalyptic prophets may proclaim novel revelations, but the closer one sticks to the energies of the earth — and that is what we are talking about here — the more likely that your line of flight emerges from a spiritual matrix of tradition, however mutant.

One might legitimately argue that within contemporary spiritual subcultures in the West — postcolonial, technologized, thoroughly disrupted by modernity — traditions of practice are either unavailable as such or hopelessly fabricated out of commodified desires for continuity and “authentic wisdom.” In general, that may be true. But this condition does not obviate the fact that practical elements of these traditions — the “algorithms” that drive aspects of Taoist energetics, yoga, tantra, and even alchemy — have been transmitted by individual teacher-bodies into bohemian, psychedelic, New Age, and “alternative” subcultures. In addition, these subcultures, despite their provisional and open-ended character, invariably fabricate their own lineages, traditions, and networks of transmission. In other words, the contemporary production of the BwO, at least in the context of exotic mystical practices, drugs, sacred sex, and trance dancing, constitutes a “tradition” within the west, one that, while essentially anti-authoritarian, is passed on and refined as much as it is constantly re-invented.

The question of tradition interests me because Goa has become the site, both mythical and historical, for a sort of tantric hand-off between an earlier generation of Western trance dancers and today’s psychedelic ravers. Whether or not Goa is the core source of rave spirituality, the freak colony has grown into a spiritual origin, a source. But this does not make it simply another myth. In a roundabout way, the narrative surrounding Goa in itself affirms the spiritual aspirations and gnostic power of today’s global psy-trance scene. Because for all its rhizomatic multiplicities and cyberdelic futurism, the scene demands a backstory for its embodied illuminations, a context-building tale about initiation and transmission. For it is in telling such a tale that tonight’s body-without-organs grows to encompass the eternal return of its progenitors, and that something rather ancient can find its dancing feet again.

***

After taking a one-stop hop from New York to Bombay at the tail end of 1993, I transferred onto one of India’s recently deregulated flights to Goa. At the airport I caught a taxi up to Anjuna Beach, which my Lonely Planet guidebook told me was one of the last hippie hold-outs. We drove through broad rice patties and thick palm groves, and then into Anjuna, where the taxi dumped me off on one of the village’s countless sandy paths.

After scoring a room in a local villager’s house for two bucks a day, I was ready to ring in the New Year. Though I didn’t know the location of the party, the auto-rickshaw driver did, and I hopped into his sputtering three-wheeled machine. The waning moon filtered through the cracked window, only a few days past the full. Soon we arrived at the party site: a tree-lined hill about a mile inland from Vagator beach.

The dance area was still quiet when I wandered in, nothing but of a clearing lined with black lights. A few yards away, scores of chai ladies from nearby villages had laid out rows of straw mats and piled them high with fruit and cookies and bubbling pots of syrupy brew. People flopped out on the mats by the light of kerosene, smoking, sipping chai from scalding hot glasses, awaiting the dance. The international crowd was pretty evenly divided between furry freak brothers and hip clubbers strutting their cyberdelic stuff: incandescent sneakers, flared fractal jeans, floppy Dr. Seuss hats stitched with the bright mirrored cloth of Rajasthan.

Then an ambient raga began: the bubbling tablas and droning sitar of an Orb remix. A crowd of young Indian men in dress shirts and slacks set off fireworks. Then the beats bubbled into an insistent digital pulse soon punctuated with kicking bass thumps. Computer bleeps, digital winds and melancholic arpeggios gradually layered the incessant beat, which approached the 150 bpm mark where dancing breaks down into jitters and tics. The freaky dancers rode that edge, keeping the flow in their hips as they chased the looping liquid melodies with their hands. Occasionally a disembodied voice floated through the mix, triggering mindfucks left and right: “Music from the brain.” “There are doors.” “Everybody online?”

I made my way to the DJ booth, squeezing between dancers spinning in exotic rags and local children begging in filthy ones. Behind the mixing table stood an old school hippie: long dreads, black jacket and leathery, sun-burnt face. The man was slapping tapes into two DAT players run through a pint-size mixer. Alongside his stacks of black-matte cassettes stood a candle, a few sticks of Nag Champa incense, and a small devotional portrait of Shiva Shankar, sitting in ardha-padmasana on a tiger skin.

“That’s Gil, one of the best,” one of the Indians mobbing the booth tells me. What luck. Genesis had told me about Gil: an old psychedelic warrior from the Haight Ashbury, an intense being, a heavy-set bear of a DJ. “You have to find him”, Genesis had said. “He’s one of the links.” But Gil was too lost in his craft to talk.

By 3AM or so, the music grew heavier and the so-called “power dancers” took the floor: utterly absorbed, ceaselessly flowing, totally dedicated to the beat. Their bodies sought to express every oscillating pulse, every twisting melody or Fourier transform, like Deadheads bonedancing in overdrive. Many shut their eyes, plunging through some private and glittering darkness while unsettling voices shot through the mix: “The last generationÉ” These people were surfing the psychedelic bardo, that liminal zone that variously evokes dreamtime and death, primal rites and apocalypse. My own limbs had first plumbed that zone during Grateful Dead shows in California in the early 1980s, especially during the legendary second sets. But in contrast to the Dead’s notoriously loose if often resplendent noodling, Goan trance seemed more economically engineered for psychedelic journeying.

Let’s be clear: most of the psychedelic characteristics of psy- trance are functional rather than simply representational. That is, they trigger and extend psychedelic perception as much as they signify it with characteristically “trippy” cues. Just as the combination of Flouro-lite dyes and black lights seems to virtualize visible objects to a suitably tweaked visual systems, the music’s sonic afterimages and timbre trails disintegrate conventional spacetime and allow shimmering micro-perceptions to emerge on the melting border between soundwaves and internal sensations. Portals appear, resonating geometries that seed further cognitive and somatic shifts, while the relentless and essentially invariant rhythm — what the Australian-Goan DJ Ray Castle calls “quantum quick step” — at once anchors and fuels the voyage. Repetition becomes a carrier wave, the audible beats seemingly dissolving into pusling nervous systems whose mutual entrainment brings on a collective intensity which transcends — yes, transcends — the usual dancefloor heat.

Enough of this. Seeking relaxation and discourse, I wandered over to chai land and plopped down next to a crowd of Brits. Pete was in pajama pants and an open vest, his aristocratic features oddly framed by long scraggly hair. Hunched next to him was Steve, a skinny blond rolling a spliff.

“Have you seen The Time Machine?” Steve asked me. “There’s this noise that the Morlocks use to call the Eloi underground. That’s exactly how it was five years ago when my friends and I first came to Goa. We heard this booming rhythm in the distance. We didn’t know where the fuck we were, but we just crashed through the jungle with our torches. The sound was calling us. I got real paranoid that there was some alien intelligence directing the computers, like the Morlocks, summoning us to a place where they were gonna eat our souls.”

Pete nodded as if nothing his friend says could surprise him. “My first party, I just got the feeling I was in some spiritual Jane Fonda gymnasium,” he says. “Boom, boom, boom, and everyone going into trance. It was quite alienating actually.”

I asked them how Goa parties differed from the raves in England. “Here people know about the history of freakdom, of free-form living,” said Steve as he passed me the smoke. “That vibe is carried forward with the music. In England it’s not really freaky anymore. It’s too organized. People are wearing the right kind of T-shirts, whereas here people will rip their T-shirts apart and run down the beach.”

Steve and Pete’s comments showed how Goa functioned as a locus of tradition. How “spiritual” this tradition was depends on your definition of the term. “Free-form living” implies sensual practices and low-commitment lifestyles at least as much as it implies supernatural notions of the Tao or spiritual practices of, say, choiceless awareness. But it is precisely this “pseudo-spiritual” mix, incoherent or even repugnant to observers but rather comfortable to participants, which characterizes bohemian or freak religiosity — what I am calling its spiritual hedonism.

Steve’s reference to The Time Machine also reminded me of the almost sinister edge to psy-trance’s science-fictional imaginary, an edge most visible in the thankfully fading images and lore of the Grey aliens. Such images should curb any easy attempt to sacralize the dance floor as either a utopian site or an essentially archaic one. This is a music, a consciousness, ghosted by futurity, which for contemporary (post)humans has become a great abyss, however full of marvels. In many ways, this consciousness is a testament to the seriousness of the scene’s psychedelia, because serious psychedelia plumbs many spaces far outside conventional markers of the spiritual. If more mainstream clubbers are willing to sacralize the Teletubby bliss of MDMA, then psy-trance dancers tip their hats to the cosmic reptiles that snicker eternally from the inky depths of psilocybin. Shamanspace is no walk in the park.

But Steve’s technological paranoia also reflects the trickiness of freak transmission, with its anti-authoritarian and free-form biases. Instead of formalized rites of passage, it relies on happenstance personal contacts, the vagaries of underground media, and pure synchronicity. A defining element of this anti-traditional tradition is the emphasis on the individual’s personal experience with various techniques of ecstasy, from meditation to drugs to unconventional sex. Decoupled from the cultural constraints that characterize most traditions, ecstatic technologies carry a powerful promethean — dare we say Faustian? — ambivalence, and provide few safety nets.

In rave culture, these techniques also include the technologies and technologists (DJs, musician-programmers) that collectively engineer the dance. Submitting to such powerful electronic assemblages is nontrivial, because technology’s great question — the question of control — is always left open. As with psychoactive substances, our spiritual relation to technologies often takes on the character of a pact, an uncertain alliance. As bohemians have long recognized, such pacts in themselves imply a certain diabolism. In its very sonic logic, psy-trance suggests that the west’s colossal pact with electronic and digital technology is driving us towards a radically posthuman future. The fundamental paradox of this music is that, in its path towards the ancient trance and a life beyond Babylon, it must march straight through the pixelating doorways of the datapocalypse.

Enough of this; as the first hints of sunlight streaked the night sky, it was time to return to the dance. Dawn , I discovered that day, was Goa’s sweetest moment, both antithesis and reward for the night’s long darkness. The bpms slowed, and the bracing attacks gave way to a smoother, more euphoric vibe. According to Goa’s more self-consciously shamanic DJs, the change of pace had a ritual function: after “destroying the ego” with hardcore sounds, “morning music” fills the void with light.

As the dawn rays floated through the dusty clearing, a crazy quilt of beautiful people slowly emerged from the gloom: Australians, Italians, Indians; Africans in designer sweatshirts, Japanese in kimonos, Israelis in polka-dot overalls. A crowd of old-time Goan hippies ringed the clearing, gray-haired and beaded creatures who dragged themselves out of bed just to taste this moment. Eyes met, and flush bodies drank in the pleasure of their mutual moves. Eros charged the air, but I felt none of the sleazy, late-night vibes common to urban clubs. I recalled something Genesis had said on the phone, when he traced Goa’s mode of ecstatic dancing back to Ô60s London clubs like UFO and Middle Earth. “Unlike most popular dance, trance-dances aren’t about sexual encounter,” he said. “Instead, you dance like a dervish to accentuate your artificially induced mental state to a point that’s equal to and integrated with an ecstatic religious state. You’re seeking illumination, not copulation.”

Now I knew what Genesis had been talking about. Gil’s set was a story about illumination: Once the strong initial hook compels you to get up and go, a gradual intensification of psychedelic effects brings the bodymind into a space at once heavy and incorporeal, an exquisite dark night of the soul that more or less matches the splintering plateaus of a drug peak. Dawn proclaims a sweet return, as the rising heat and light reconnect you to the human family, to nature and the faces of all your fellow travelers, at once loving and impersonal. However deterritorialized the core of the evening, its flights were mobilized inside an essentially narrative frame — a frame that, if not fixed in the archetypal basement of human consciousness, is at least hardwired by the metabolism of psychoactive substances.

Genesis’ comment also helped me realize something about the Goan beat, which to outsiders can seem inexcusably monotonous and unfunky. By minimizing syncopation and flattening any potential sinuousness in the grooves, Goan trance releases energy from the gravity well of the hips. This redirects the pelvic undulations that anchor the more sexual energies of dance, deterritorializing them across the entire frame, and especially the upper body.

Such displacement has been explained in part by the action of MDMA, which is notorious for generating libidinal attractions that cannot, for men anyway, be genitally fulfilled. But MDMA is a secondary drug within psy-trance, and even psychedelic phenomenology only take us so far. Recognizing the misprision involved, it seems best to invoke tantra’s esoteric physiology. As Ray Castle noted, Goa’s “sound frequency alchemy” revolves around “raising the kundalini serpent energy in the body’s chakra system.” In addition to the frequent use of ascending arpeggios and digitized glissandi, psy-trance’s quintessentially impersonal beats help trigger such ascendant energies. At the very least, these highly directed vibrations serve as immediate, functional analogs for the secret life of shakti.

Such rhetoric may simply be more freak appropriation, alongside the Ganesha tapestries, Rajasthani hand-bags, and pervasive stink of Nag Champa. But I think not. In the midst of his morning mix, Gil introduced the mantra “Om Namah Shivaya,” intoned over sitars and a bubbly beat. Spinning far outside of orthodoxy, east or west, Gil knew who he was invoking. As an obscure hippie-freak poem has it:

Shiva, dread-headed lord of destruction and transformation, your electric drum heralds the close of the world.

You dance with Shakti, refusing climax, among bands of wild youths and sneaky gnomes.

Your blue throat holds the world’s poisons, its toxins and psychoactive drugs. Shiva, you are stoned.

Your serpents tongue our spines, fuck inside our cells. They proffer amines, the gnostic fruits that taste like

no

turning

back.

***

Shiva, of course, is Dionysus’ eastern twin, giving Goa’s patron saint an east-west doubleness that also marks the psycho-geography of the Indian state. As an Indian stoner I met in Mysore put it, “Goa isn’t India.” And Goa hasn’t exactly been India since the Portuguese first colonized the area in the 1600s. Then, “Golden Goa” provided the kind of oriental luxury that allowed an already waning imperialist power to really go to seed. Miscegenation was encouraged, and some adulterous native wives reportedly took to dosing their husbands with datura weed, rendering the men, as one early account put it, “giddy and insensible.”

Goa remained in Portuguese hands until India seized the region back in 1961, and the largely Catholic area was still deeply syncretic when beatniks like Eight-Finger Eddie discovered its beautiful beaches a few years later. By the end of the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of European and American freaks were streaming overland into South Asia. Though Goan beaches like Calangute and Baga did not offer electricity, restaurants or much shelter, they did provide sweet relief from the overwhelming grind of travel in the East. The impoverished locals, most of whom practiced a Western religion and were already used to Europeans, were largely accepting. Every winter a motley tribe of yoga freaks, hash-heads and art smugglers would gather, until the growing heat and the threat of the summer monsoon pushed them further on. Going to Goa was like going home for the holidays, and the freaks celebrated: Christmas, New Year’s, and especially full moons.

Many of these transients were seekers, willing to weather the rigors of Indian music, meditation, and yoga in order to taste their spiritual fruits. But, as heirs to bohemia, their desires for exploration also encompassed drugs, orgies, and general freakiness. This mixed mode is what I characterize as spiritual hedonism. Here the western affirmation of the body and its pleasures, most certainly including aesthetic experiences, is no longer strictly contrasted with religious forces. Instead, pleasure itself is refined beyond mere sensuality, ramping up into an outr spirituality hungry for immediacy, energy, weirdness, and unchurched gnosis. Because of its taste for intensities, spiritual hedonism even includes room for strict asceticism alongside indulgence and a variety of “middle paths.”

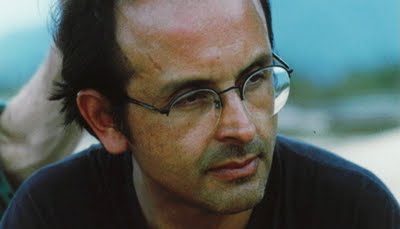

Gil the DJ — who goes by Goa Gil in the West — was one of those original spiritual hedonists. Gil grew up in Marin County in the 1960s, and fell in with Family Dog, the loose freak collective who sparked San Francisco’s concert scene before Bill Graham moved in. In Ô69, fed up with “rip-offs and junkies and speed freaks,” Gil made his way to India, where he encountered the sadhus, Hinduism’s wandering holy men.

Hymns in the ancient Vedas describe these “longhaired sages,” living in the forest, covered in ash and drinking soma, the ancient holy brew that some scholars believe was psychedelic. Today, millions of sadhus still drift about the land, gathering at huge holy festivals, or holing up in the Himalayas to practice yoga. Some are strict ascetics, some are simply beggars, while a select group, the followers of Shiva, resemble nothing so much as Hindu Rastafarians. These Shaivite sadhus wear their hair in long dreads and find spiritual sustenance in charas, India’s yummy mountain hash. Before they inhale, the Shaivites cry out “Bomm Shiva!” the way Rastas bark “Jah!” The power of the herb they identify with the power of shakti.

Not surprisingly, the freaks took to the sadhus. Gil went whole-hog, living in caves, wearing orange robes, and coaxing the Kundalini up his spine. But he still found his way to Goa every winter, where he banged on acoustic guitars at the firelit drum circles. When Alan Zion smuggled a Fender PA in overland, live electric jams and prerecorded rock became their yearly soundtrack.

According to Gil, these parties were the direct ancestors of raves. The crucial transition — from guitars to electronic dance music — occurred at the impressively early date of 1983, when two French DJs named Fred and Laurent got sick of rock music and reggae. About the same time that Derrick May and Juan Atkins created the futuristic disco-funk first called “techno”, Fred and Laurent used far more primitive tech — two cassette decks — to cut-and-paste a nightlong aural journey out of industrial music, electronic rock, Eurodisco and experimental bands like Cabaret Voltaire and the Residents. Stripping out all the vocals, they designed their mixes to amplify the bacchanalia of hard-traveling psychedelic partiers, and it worked. Soon hipsters started slipping them underground tapes from the West. When the German trance maestro Sven Vth first showed up in Goa, he was amazed to discover that Laurent admired his earliest and most obscure 16-bit recordings.

Gil and his friend Swiss Ruedi quickly followed the Frenchmen, but the techno transition was not smooth. The freaks were attached to their Bob Marley, their Santana, their Stones. Once Ruedi had to enlist a bodyguard to ward off some rocker’s blows. But eventually Goa’s DJs managed to plug the functional needs of heavy psychedelic trance dancers into the emerging electronic landscape of machine beats and trippy instrumental remixes. Within a few years, a distinct sound emerged.

When I interviewed Gil, he was adamant about the spiritual core of the Goan parties. “When I was 15, I’d burn certain colored candles and certain incense and invoke spirits. Now I’m basically just using this whole party situation as a medium to do magic, to remake the tribal pagan ritual for the 21st century. It’s not just a disco under the coconut trees.” He paused to light up a Dunhill. “It’s an initiation.”

At the core of this initiation, according to Gil, is trance, an experience of psychoactive grace. Here is the description he gave to the San Francisco writer and trance DJ Michael Gosney:

When there’s no problem, and everything’s set up right, and the music just flows, then it can come to the point where you go into the trance, and everybody’s going in a trance. And it builds and builds. When it’s just perfect, and it’s a perfect song for the moment, perfection opens up in that moment, and it keeps sustaining itself. Then it becomes so perfect in the moment, with the trance, magic starts to happen. Everybody all at once will start to get tingling up their spinal column, and outside of their skin, like your hair’s standing on end. Everybody will be getting it all at once. It will be so perfect in the moment that that feeling just sustainsÉ.It can build and build and build til it comes to a point where it goes ssssssssshhhh through everybody all at once, like a bolt of lightning.

Gil’s language lends itself equally to a Deleuzian or tantric gloss, but the real strength of his claims lies in their core appeal to experience. Besides a certain inherent ineffability, such experiences emerge as largely unspoken intensities within a cultural context that eludes and even actively undermines the usual anthropological markers of religion. The psy-trance party allows the commingling of age-old ecstatic techniques with attitudes and technologies that reject tradition in the name of an open-ended, novelty-seeking alternative popular culture. This mixed quality helps explain how and why the pagan primitivism of psy-trance’s gnosis is also wedded to profoundly apocapytic expectations. We return to move forward, accelerated.

As if on cue, Gil slapped on two remixes he made while visiting San Francisco the previous summer. The original tracks were made by Kode IV, a German duo who bragged in interviews about producing techno tracks in five minutes. Gil blasted the tunes at ear-splitting volume, the first of which sampled Pope John XXIII, Aleister Crowley dropping Enochian science, and a sadhu shouting “Bum!”. Then Gil played his “Anjuna” mix of “Accelerate.” He towered over me as he repeated word for word the sample he cribbed from some flying saucer movie: “‘People of the earth, attention.'” Gil’s eyes bored into mine, as if he was channeling the message directly from the aliens. “‘This is a voice speaking to you from thousands of miles beyond your planet. This could be the beginning of the end of the human race.'” For a moment, I could hear the Morlocks call.

***

“Goa Gil” self-consciously presented himself as a carrier of tradition, and he slagged a number of Goa’s younger DJs for being on ego trips instead of cultivating the proper devotional attitude. The idea that DJs carried the burden of the tradition made me even more intrigued to speak to Laurent, the French DJ who had pioneered the electronic parties back in ’83 but, to my knowledge, didn’t spin at parties anymore. Gil hadn’t been too encouraging. “He probably won’t talk to you. He’s very mysterious.” But he told me where Laurent could be found every day: in the last chai shop on little Vagator beach, playing backgammon.

I was not and never will be cool enough to ride an Enfield bike, so I puttered my lame moped towards the cliffs north of Anjuna. Clamoring down bluffs packed with coconut trees and tall, pale teepees, I bumped into a Belgian I had met New Years Eve. He lived in one of the teepees and loved it. I told him how ironic it was, that the temporary shelters of the nomads mistakenly called “Indians” by Europeans were now housing European nomads in India. This confused him.

The last chai shop on the beach was a grimy hut filled with folks as weather-beaten as the long wooden tables they hunched over. Some played backgammon, others sipped orange juice and chai, and everyone smoked. A sour-faced Indian girl serving up a bowl of porridge and honey pointed to Laurent: a scrawny guy in a Japanese print T-shirt, tossing a pair of dice. The man was gaunt and bloodshot, and his teeth were in bad shape. He looked like a hungry ghost.

Laurent gave a caustic laugh when I asked to interview him. But I took his lack of an obvious refusal for a go-ahead. He kept slapping the tiles with his partner Lenny, a balding, washed-out middle-aged Brit. “Art does not pay so I am forced to gamble,” Laurent explained in a throaty Parisian accent thickened with sarcasm. He fiddled with my Sony mini-tape recorder, clearly bent on soaking this little episode for all the humor it was worth.

“The spy in the chai shop,” mused Lenny as he drew heavily on a cigarette. Laurent cracked up, his laugh degenerating into an asthmatic coughing fit.

“You know, it used to be very bad here for spies,” Laurent said, with mocking concern.

Despite his sarcasm and creepy laughs, I took a liking to Laurent. He also proclaimed Goa’s fundamental contribution to rave culture — “This is the source of the source” — but he was low-key about it all. No mysticism, no nostalgia. “I am a simple person,” he said. He gave his friend Fred the credit for first mixing electronic tapes at the parties, but said it was too experimental for the crowds. “Nobody liked it. Then I played and made it so people liked it. And now people like it all over the world.” Laurent then let slip that he had some of his early party tapes, and I pressed to hear them. “Ah, this would be very, very expensive,” he mocked. “We must draw up a contract.”

Laurent told me he played the Residents, Cabaret Voltaire, Front 242 — but only after cutting out the vocals, which irritated him. I kept pressing him about his style. He paused, and looked me in the eye. “Here you make parties for very heavy tripping people who have been travelling everywhere. You have to take drugs to understand the scene here, what people are thinking.”

Unwilling to invoke mystical forces, Laurent’s comment raises a vital point: how we address the spirituality of psy-trance turns significantly on how we assess the spirituality of psychedelic use, not in some half-imagined Neolithic or shamanic context, but inside western subculture. This is not the place to hash out this question, but I would like to suggest that the spirituality of these compounds is, for moderns away, fundamentally ambivalent. Even the name is up for grabs: many proponents now use the term entheogen, suggesting “becoming the divine within,” rather the more secular term psychedelic, meaning “mind-manifesting.”

This shift of course merely replaces on load of baggage for another. Whatever else they might also be, “enthogens” are material compounds whose evident physiological action can be used, at least superficially, to support a reductive argument for the merely neurological basis for spiritual experience. Moreover, however much we may appreciate and mimic the use of psychoactive plants in traditional sacred contexts, such plants, and even more so their chemical cousins, are also commodities and controlled substances operating within globalized networks of production, exchange, criminality, and law.

As Goan parties prove, some of the most exalted states of the human spirit — cosmic communion, the integration of self and other, the sense of timelessness — can be triggered with molecules, beats, and electronic culture. Even if you sacralize these elements, couching their technical power in supernatural over-beliefs or the performative spirituality of the dance itself, there is still the problem of the morning after — which, given the psy-trance emphasis on dancing well into the next day, is more of a metaphor than usual. Think of it as a metaphysical morning after, a period of deflation, recovery, and regrouping. It is during this period, which is rarely given much focused attention, that the “modern” and hedonistic drug-like character of the psychedelic experience becomes most evident. Leaving aside the somatic costs, bohemian scenes rarely provide the sort of well-defined cultural contexts that, in traditional psychoactive societies, allow people to integrate their experiences into everyday life.

In many ways, this “psychedelic agnosticism” is a good thing, a distinctly modern feature that goes a long way toward squelching authoritarian tendencies or religious delusions. Moreover, many looser and more ad-hoc quasi-spiritual contexts have emerged in the psychedelic and psy-trance community, as individuals and groups seek to deepen their experiences through art, environmental activism, meditation, yoga, group processing, or any number of occult techniques and interpersonal therapies. And the increasing popularity of ayahuasca sessions has focused attention on the spiritual intentionality surrounding serious psychedelic use. Because without the long-term transformation of the psyche and its network of embodied relationships, the ecstatic trance may do nothing more than stage its own repetition — no longer as a meta-erotic ritual of rhythmic return, but as habit and jaded escape.

***

Towards the end of the 1980s, when Goa’s electronic dance music had already become a distinct style, the tracks played at parties were produced in the West with the colony in mind. But some trance cuts were home-made. I met one German named Johan, a handsome fellow who had released tracks under the name Mandra Gora and lived in a huge house in a small inland village. His room contained little more than a bed, a bhatik print and his gear: Macintosh PowerBook, Akai sampler, keyboard, DAT deck.

Johan arrived in Goa in 1988, when the trance scene was totally underground. “It was like a poker game no-one could follow,” he told me. Johan was not into DJing Ñhe was one of those power dancers who treated the night as one long track. “With a combination of good music, a good spot and good dancing, it’s like a cosmic trigger goes off,” he said of Goa’s greatest rites. After a night’s ride, Johan would return to his home studio, transmute his vibes into new tracks, dump the bytes onto DAT, and pass the tape onto his DJ friends. “It was like a perfect feedback loop.”

Unlike most music-makers in Goa, Johan didn’t care about talking to a journalist, because he knew that, in some sense, it was already too late. Goa trance was just beginning to emerge as a genre in the West, and he was going to take advantage of the future he accurately saw coming, a future of packaged tours, label hype, and marketed identities. As saw it, the obscurity necessary for a genuinely esoteric underground was no more. “Soon we’ll have a global digital network where everyone will know where everybody is all the time.” He looked at me impassively. “What you’re here to write about is already dead and gone.”

It’s a common story in subcultural scenes, especially musical ones: the better days were before. But in Goa this familiar hepcat tale directly recalled the religious paradigm that lurks beneath it. Though generally centered around a charismatic leader, the early days of a religious movement are typically characterized as possessing a directness and spontaneity later lost as the movement’s forms and dogmas become routinized while the word spreads into larger populations. In its need to generate images of Goa’s spiritual authenticity, the psy-trance scene has partly transformed the object of its desires into a simulacrum.

Johan’s comment brought on the predictable melancholy of belatedness. Anjuna now seemed to me like a freak Club Med, with yummy restaurants, “authentic” primitive digs, and a currency that might as well have been monopoly money. I grew tired of interviewing DJs, most of whom displayed the same snotty power games endemic to western club scenes, although here they were supercharged with the esoteric withholds of a gnostic elite. And the superficiality of the scene’s purported relationship with India’s culture, not to mention its people, grew more and more dispiriting. I began to sympathize with one gray-haired Frenchman I met, who first came to India in the early 1970s and had become a master of sarod. “These new people have no idea,” he complained. “They didn’t come overland, they didn’t have to find their own food, and they never really got lost.”

One hazy, hot afternoon, I was hanging around the Speedy Travel agency waiting for a fax. A steady stream of freaks bought tickets for Hampi, in the neighboring state of Karnataka. “It is a very ancient place,” a bronzed Dutchman rolling a Drum told me, describing what sounded like a Hindu Stonehenge 300 kilometers to the east. “I hear some German with a bus will throw a full moon party in the temple there.”

That was all I needed. A week later, a creaking local bus spit me out at Hampi Bazaar. Named after Shiva’s consort Parvati, Hampi is not exactly an “ancient” placeÑthe Hindu city fell to rampaging Moslems during Queen Elizabeth’s reign. But the ruins that spread out for miles around the small, freak-filled village exuded a haunting, archaic calm. Green parakeets roosted in silent temples encrusted with jesters and monkey gods. Rice paddies lined the nearby Tunghabhadra river, which snaked past huge mounds of desert boulders. Across the river, a number of sadhus tended Shiva shrines and passed the pipe with hearty Caucasians who had turned their backs on the minimal comforts of the village.

I spent the days poking through ruins, munching cashew curry, or dozing on the mats at the Mango Tree, a simple and peaceful outdoor hash cafe on the banks of the lazy river. Local tourist regulations insisted they post an anti-drug sign, but the staff kept slipping their “Smoking Psychotropic Drugs Not Allowed” announcement behind a poster, so all you could see was the word “Smoking.” Sometimes the white sadhus from across the river would show up, with their orange robes and mala beads and ancient, fading biker tattoos. They were no joke, these white sadhus, however eccentric they may have been. I heard a marvelous tale about one fellow who decided to deepen his practice by vowing to spend a month sitting in one of the caves that peppered the landscape. After beginning his vigil, he was so pestered by other freaks coming to gape at his feat that he wound up letting a room in the village in order to fulfill his vow.

Gil had criticized the whole idea of a Hampi rave before I left, arguing that Hampi was where you hung with sadhus, not where you threw parties. His comment suggested that despite the supposed spirituality of a good Goan fete, their hedonic logic did not thoroughly cover one’s spiritual possibilities. Nor did it fit the psychogeography of spiritual India, whose possibilities far outshone a mere rave.

In the week leading up to the full moon, I could understand Gil’s reservations. A noticeably trendier crowd moved into Hampi: nattier threads, better cheekbones, more cash. Rooms filled to capacity, kids slept on roofs or in temples. Finally a huge tour bus drove up and parked in the dusty bazaar. Slogans blazed across the side: Techno Tourgon, LSD 25, Shiva Space Age Technology. Jrg the DJ had arrived.

I finally caught up with Jrg on the day of the full moon. The BBC has just finished interviewing him, and the man was beaming, his blue eyes glowing with a mad lucidity. A huge bronze Shiva Nataraj danced on the dashboard, an image echoed in the Shankar tattoo on Jrg’s taut naked belly.

Jrg was pure freak, too maniacally enthusiastic to cop a snobbish DJ attitude. “I used to be a typical heavy-metal rock’n’roller. Now I am addicted to techno,” he said. “For five years time now I listen to nothing else. Except meditation songs in the morning.” Like many technofreaks, Jrg’s first Goa party was nothing less than a conversion experience. “You can laugh, but it was like seeing a keyhole to God,” he said in a hoarse voice. He’d been back and forth to India ever since, selling land cruiser parts at the Chinese border, DJing parties around Kathmandu, dipping in the Ganges with the sadhus at the holy city of Haridwar.

“I’m a little bit extremist,” he admitted, grabbing a cigarette from a pack lying next to a crumpled photo of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. The previous year, after a month in Goa packed with drugs and dancing, and with hardly any DJ experience, Jrg set up his gear in Hampi’s underground Shiva temple and threw the archaeological area’s first rave. “After that party I feel like this big hole. I sat for another month under a tree. Nothing inside anymore.” He fiddled with the 5-inch Sony mini-discs he uses instead of DATs. “But believe me, to be empty and open to everything is exactly the right position when you come to India. You have to improvise.”

Only hours before moonrise, Jrg was still improvising. After spending days finding the right official to bribe in order to throw a party, he made his case. “We talked for hours. We got to know each other very well. Then he said no.”

So in the fading sunlight, Jrg decided to cross the river into another district. He and his crew lugged their gear down the river’s edge, and loaded the equipment into the same round, leather-covered basket boats the Portuguese explorer Paes noted when he passed through Hampi in the 16th century. Darkness descended, and they had no idea where they were going.

Hours later, hundreds of us ferried across the river in the same leaky boats. We threaded our way past crumbling walls and along paths lined with ominous palms, following a trail of lanterns a mile or so onto a treeless plateau of moony rock. We glimpsed black lights in the distance, hear the dull thud of techno. No chai ladies tonight. We were partying in Bedrock.

Jrg crouched over his machines beside a large boulder dry-painted with the appropriate icons for the night: peace, OM, anarchy. Though his music was old, his mixing rough and his generator tepid, Jrg soon sank the dancers into the groove. I start taking snapshots. Unlike Goa, where blissed-out hippies transformed into ferocious assholes at the sight of a camera, nobody here cared. An Indian sadhu passed through the crowd, joshing with a grizzled Italian in orange robes who occasionally whipped out a conch shell and blew. Who is the holy man? I wondered. Who is the pothead?

After a bug-eyed Jrg led us careening through an eon’s worth of cartoon wormholes, dawn arrived, dusting the rocks with pale purples and rusty reds. Fairy-tale temples emerged in the distant mist, but it was no hallucination. Jrg climbed up on a rock and pumped his fist, exhorting us into a supreme embrace of the moment. The shivers came, the lightning flash, the exquisite plateau: it was night-time, daytime, alltime. As the rising sun and the setting moon touched the horizons on either side of us, the heavenly bodies seemed to align and balance the fragile, fantastic orb on which we dance.

What follows such moments of pop gnosis is, as they say, another story. The great problem with experiential spirituality is that experiences pass. As I mentioned above, if there is no context or tradition of integration, then it’s tough to say what will follow. We do not live by intensities alone, and destratification, particularly involving psychoactive substances, can leave quite a mess in its wake. Following the 1960s counterculture, we should be wary of any claims, spiritual or otherwise, that place an ineffable electronic gnosis at the heart of its global aspirations.

But it’s easy to grow pessimistic at this hour, and so I’ll leave the final words to Gil, whose hopes about Goa’s initiatic trance-dance blast are pure religious sentiment:

“That’s when the seed is being planted in everybody’s consciousness at the same time. The spirit has come and given that grace, and they’ve gotten something. Hopefully, they’ll go home, and they’ll live in truth, and improve their lifeÉ.They’ll start to be more spiritually oriented, and hopefully that seed will flower and bloom. Light a light of love in their heart and mind. Make them more sensitive and aware of themselves, their surroundings, the crossroads of humanity, and the needs of the planet.”