Gurdjieff and de Hartmann’s Orchestral Music

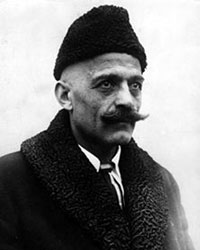

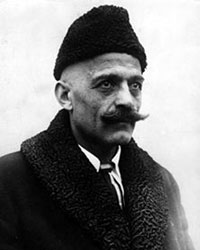

Whether you regard him as a master of awakening or a mustachioed flim-flam man, G.I. Gurdjieff stands as one of the most fascinating spiritual teachers of the twentieth century. A charismatic and confounding Greek-Armenian born in the Caucasus, Gurdjieff spent decades scouring the lamaseries, hermitages, and dervish haunts of the East searching for the keys to the human psyche. His resulting system — which he called “the Fourth Way” or simply “the Work” — detailed the operation of the “human machine” and laid out a peculiar if psychologically sophisticated course of awakening. Both before and after Gurdjieff’s death in 1949, the Work attracted scores of artists and intellectuals, including P.D. Ouspensky, Rene Daumal, and the British writers Katherine Mansfield and Algernon Blackwood.

One of Gurdjieff’s principal students was an aristocratic Russian composer named Thomas de Hartmann. From 1924 to 27, master and student composed hundreds of solo piano pieces. Drawing from his prodigious memory, Gurdjieff would whistle or hum melodies and rhythms learned on his travels—dervish prayers, Kurdish dances, Orthodox hymns—and De Hartmann fleshed out these sketches. (There is some evidence that Gurdjieff could write music as well.) Though saturated with Russian color, De Hartmann was a modernist—he had written winning music for a Nijinsky ballet, and, after befriending Kandinsky, penned an article on “Anarchy in Music” for a Blaue Reiter journal. But the shining little gems he cranked out with Gurdjieff seek another, more inward sort of rupture than modern anarchy. This is a music of subtle transport—at once consoling and implacable, like ancient lullabies for haggard desert sages. Though deceptively simple and overtly Orientalist, the Gurdjieff-de Hartmann oeuvre is not naive magic carpet music but mystic minimalism before its time—folkloric perfumes whose odd rhythms and melodic approximations of Eastern microtones strive, like Kandinsky’s Theosophical paintings, for an impersonal and objective invocation of sacred forces.

For decades, this music was kept largely within Gurdjieffean circles. Keith Jarrett made a decent recording of some of the sacred hymns for ECM in 1980, while Fourth Way practitioner Robert Fripp produced a stern but choice Elan Sicroff recording a number of years later. Now there are tons of discs out there, including a few complete editions of the piano music. One notable recent collection comes from the American Laurence Rosenthal, who, like basically all of the music’s major interpreters, is a follower of the Fourth Way as well as a pianist. In his notes, Rosenthal writes that he was initially turned off by what he felt was the music’s amateurish air of “trivial Oriental exoticism.” But he eventually came to appreciate the depth beneath the surfaces, a depth, he wrote, that had less to do with the specific musical language than the questions—and answers, or at least suggestions—framed in that language.

Gert-Jan Blom’s massive Oriental Suite package—four CDs, plus an informative and lavishly illustrated hardcover book—adds another dimension to Gurdjieff’s spiritual music. In the early 1920s, Gurdjieff was pushing the Sacred Movements, a vigorous sort of Sufi yoga dance designed to produce the mastery and awareness of the human machine. De Hartmann and Gurdjieff composed music to accompany these Movements, and in 1923 and ’24, this music was arranged for orchestra and performed, along with the Movements, at major symphony halls in Paris and America. With obvious devotion, Oriental Suite reconstructs these rare public programs, as well as a later work called “Oriental Suite” that de Hartman orchestrated after his master’s death. Blom, who has also released a prodigious collection of Gurdjieff’s spectral harmonium improvisations, enlisted Holland’s Metropole Orchestra, conducted by Jan Stulen, to record two different versions of the program, the second one reflecting the smaller orchestra that Gurdjieff was forced, for financial reasons, to use in America.

Despite the forceful tunes, this music does not draw you in with the moody intimacy of the piano works. Because the pieces were designed to support ritualized dance movements, many of them have a plodding, didactic beat, and pretty incidental themes which are rarely developed. (One wonders what an enthusiastic American journalist meant when he wrote that the music “outjazzed jazz.”) But there is a rough magic here, carried in the witchy reeds and the evocative, stately melodies. Like the Alan Hovhaness of “Mysterious Mountain,” this is tonal modern music shaped by deep spiritual romance. As such, it can trigger a sense of otherworldly transport, though sometimes the other world conjured up resembles an early Hollywood snake charmer epic. Taken as a whole, Oriental Suite will speak most directly to Gurdjieff afficianados interested in the lore of the Sacred Movements—indeed, one of the many pleasures of the whole package is its air of intelligent, fannish devotion. But the strongest pieces—”Initiation of a Priestess,” “Pythoness,” the serpentine “Turning,” and “Big Group,” which in some manner or another is related to the enneagram—leave, in their wake, a sense that something truly enigmatic has passed by.

Oriental Suite is also a slippery sonic document of the Orientalist imagination that fed the currents of occult modernism that flourished throughout Europe and America in the 1920s. The French program described the music as “hieratic melodies of the remotest antiquity,” but one cannot really trust a trickster like Gurdjieff, can you? Though we are told that the pieces called “Obligatories” descend from a mystic school that inhabits “the large artificial caves of Karifistan,” Blom notes that the Obligatories don’t sound very Eastern at all, and that one of them is a Polish mazurka. True, Blom’s research has convinced him that much of Gurdjieff’s material is genuinely traditional. But the air of authenticity that pervades his best music with de Hartmann, here and elsewhere, has nothing to do with ethnomusicology, but with whatever “science of vibration” lends certain music the cosmic coherence of a desert’s night sky, dusted with stars and an elusive sickle moon.