70s Christian rock

Next time you see some young folks flexing their subcultural muscle, take a closer look. Along with the baggy hoodies or the four-fin surfboards, you might catch a telltale sign of the Risen Lord: an ixthus fish tattoo or a T-shirt that looks like the wrapper for Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups but says, “Jesus: Sweet Savior.” Traditionally, American fundamentalists resisted secular youth scenes and their sock hopping, sinful ways, but contemporary Christians believe that resistance is futile. Evangelist ministries and young believers have opted to enjoy pop culture’s manic energy and style while splicing in inspiring messages and strict rules of moral conduct.

The Christian embrace of hip youth scenes can be traced, like so much, to the cultural ferment of the 1960s. Given that we are all weathering a Summer of Love flashback, it might spice up the tired images of the Haight Ashbury rebels to realize that a few of them were Christians. These mystic hippies sparked the mass Jesus People movement, which injected a distinctly Christian feeling for love and apocalypse into a counterculture already up to its mala beads in love and apocalypse. By the early 1970s, a new Jesus had hit the American mind—communal, earthy, spontaneous, anti-establishment. And this Jesus continued to transform American worship long after the patchouli wore off, inspiring a more informal and contemporary style of communion and celebration that, while holding true to core principles, unbuckled the Bible Belt from American Christian life.

One of the earliest and most influential Jesus freaks was a guy with the fabulous name of Lonnie Frisbee. As told in David Di Sabatino’s excellent 2006 documentary Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher, Lonnie was a tripped-out young man who grew up in Orange County, Calif., saw God on LSD, and became a Christian in the Haight. Keeping his duds and long hair—not to mention his charismatic air of innocence and spiritual conviction—Frisbee hooked up with straight-laced pastor Chuck Smith. Together they began an enormously popular youth ministry at Smith’s Calvary Chapel, a revival that almost single-handedly transformed the hippie Jesus vibe into a mass phenomenon. Jesus became a long-haired revolutionary of love, a real Superstar, and his followers used underground newspapers and beachside baptisms to turn others on to the convulsive power of the Holy Spirit.

They also used rock ’n’ roll. Indeed, while you can debate just how much today’s suburban megachurches owe to the Jesus movement, there is no question that CCM—contemporary Christian music—owes its billions to the freaks. One of the best things about the Frisbee documentary is the soundtrack, which has just been released on CD. The collection is not the great Jesus Freak folk-rock anthology we need (or at least, I need), but it complements some of the fascinating reissues that have emerged over the last few years, including very obscure records by very different artists such as Azitis, the Search Party, Fraction, the New Creation, and the enchanting Catholic folk group Silmaril.

The Frisbee soundtrack features a few of the better folk-rock acts that were popular among the kids at Calvary Chapel, but the comp is dominated by multiple cuts from two powerful blues-rock combos, Agape and the All Saved Freak Band. Agape was one of the first Christian rock groups—it began in 1968 when Fred Caban, a guitar nut from Covina, had a transformative experience in a Christian coffee shop in Huntington Beach run by the Berg family (who would later spawn the notorious cult the Children of God). Soon Caban formed Agape and made two albums of aggressive psychedelic blues-rock in the mode of Cream or Hendrix. The trio was way too fuzzy and raw for the local churches, so they spread the word playing school assemblies, local coffeehouses, and free concerts in the park.

Some psych collectors have pegged Agape as a band that’s better in rumor than in reality. But though the music is derivative and sometimes poorly played, Caban’s playing and singing sounds inspired, at once snarly and innocent, swaggering and sincere. Their best cut here is “Wouldn’t It Be a Drag,” a sort of Christian inversion of Hendrix’s “If 6 Was 9.”* During the chorus, Agape announce that “He ain’t no religion/ You’re set free with love from the Son Yah!” It’s an apt reminder that a lot of Jesus People were not clinging to conventional religion in order to escape the burdens of hippie seeking, but that a direct experiential connection to Jesus was the very resolution of their search.

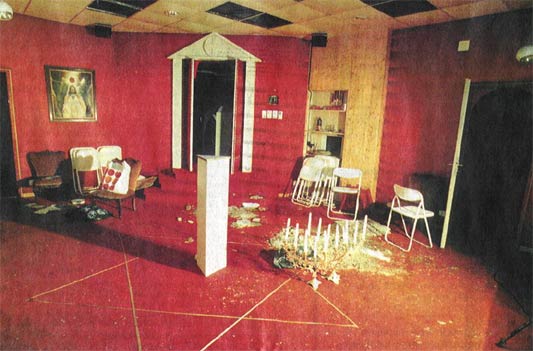

The All Saved Freak Band is a different kettle of fish—at once more powerful and more disturbing, and a reminder of how apocalyptic convictions, Christian or otherwise, can go sour. The band began when a drugged-out Chicago guitarist named Joe Markko moved to Ohio, where he met a fiery street pastor named Larry Hill. Convinced that the Chinese and/or Russians were coming, Hill set himself up as patriarch of an isolated survivalist Christian commune, replete with guns and goats. When he performed, Hill wore a wide Amish hat and a priest’s habit, and he sang to hector and convert. But the band didn’t really gel until Hill and Markko were joined by Glenn Schwartz, an incendiary blues shromper who had played guitar for the James Gang but had publicly renounced commercial rock. Living collectively, the band made a handful of intense and very strange records, including the Tolkien-inspired folk-rock rarity For Christians, Elves, and Lovers. In 1975, in response to Hill’s authoritarian brutality, Schwartz’s family attempted to kidnap and “deprogram” the guitarist. The attempt failed, and the band’s third record was called Brainwashed.

There is an extraordinary urgency to All Saved Freak Band, whose combination of righteousness and rock anticipates the stance of straight-edge hardcore but who also manage, at least sometimes, to be good-humored, down-home, and lovely. (Their use of cello in a rock context was as prophetic as anything they did.) On the Frisbee soundtrack you can hear Hill’s increasingly creepy mania best on “Sower,” which, though it was recorded in the late ‘70s—a time when the growing industry of CCM was making its saccharine pact with the pop devil—crackles with apocalyptic power and the desire to use the rock song as a vehicle of total transformation. “Hurry/ Take what you’ve got/ Do with it what you can.” Time was indeed running out—at least for Hill, whose commune was soon to collapse in a flurry of allegations about the usual cultish evils. Though it may be hard to square the All Saved Freak Band with the slick suburban profile of CCM, they remain formative figures in the genre, with Hill’s messianic intensity providing the essential rock ’n’ roll element of risk.

The man who inspired all this sonic glory, Lonnie Frisbee, came to a more surprising end. Though he was sometimes married, Frisbee was into guys. He struggled privately with his “sin,” and Christians debate about whether to call him gay, but he certainly lived life large. In 1993, Frisbee died of AIDS, raising issues that most people in the evangelical community would rather ignore. Though the man had sparked two of the most dynamic Protestant revival movements to appear over the last 30 years—Calvary Chapel and later the Vineyard—his catalytic role had largely been swept under the carpet until Di Sabatino made his documentary. In letting Frisbee drift into obscurity, the inheritors and benefactors of his ministry were not just being homophobes. They were also distancing themselves from his whole era of rebel signs and funky wonders—a convulsive period of uncorked spirit whose troubling urgency and sweet idealism is perhaps best accessed today through the curious and sometimes amazing music the Jesus People made.