Copyrights and Crime

Shortly after returning from Burning Man this last week, I hit the blobular button on my answering machine and heard the voice of a reporter who said she was from Billboard magazine. She wanted to talk to me about the Beirut advance leak that had apparently stirred up a flurry of email. I had no idea what she was talking about, and left a message for her to that effect.

Then I checked my email and discovered a number of furious and threatening emails from a dude named Ben Goldberg, who runs a pretty cool indy rock record label in New Jersey called Ba Da Bing. Goldberg has put out good records by acts I love and have reviewed favorably over the years, like Comets on Fire and the obscure and mighty Dead C. One of his forthcoming records, due out next month, is The Flying Club Cup, the second release from Beirut, a one-man bedroom band from Albuquerque that put out last year’s The Gulag Orkestar, a marvelous folk-rock Balkan fantasia. As these emails made clear, Beirut’s sophomore release had been leaked to an online file-sharing network around August 26th. Labels hate this kind of shit, which is why many of them are marking their advance disc with digital watermarks. And in this case the digital watermark attached to the uploaded file pointed squarely at yours truly.

For those of you who have not squandered your adult life writing about popular music, some background may be in order. Record companies have been supplying music critics with free copies of their releases for decades. In fact, free and early-release records is one reason that many folks get into this dubious bag in the first place. Believe you me: many a dark day of freelance frustration has been redeemed by the Christmas horde of media product on the doorstep.

Over the years, I have received hundreds and hundreds of LPs, CDs, even cassette tapes. Many of these releases have been advance recordings handed out months ahead of official relief, a gap in time designed to give critics a running start for long lead publications like magazines. Advances, which these days are sometimes just CD-Rs, generally come packaged in next to nothing—a plain cardboard sleeve or the occasional white label.

Advances are weird things—I generally don’t request them, and yet they are given to me, and yet they are not mine. Technically, the physical advance or promotional recording belongs to the record company, and is considered to be loaned to the writer, who, needless to say, signs no contract. Some promos are even stamped with the Indian giver command: Must be Returned on Demand of Recording Company. Ha! Scruffy freelance writers or mag editors almost universally treat these objects as their own property—property that is either hoarded or dispensed with. Usually, but not always, this means being sold—an act which, along with any form of transfer, is not only against the rules but is, as any haunter of used record stores knows, widely practiced throughout the known universe.

The rise of file-sharing has sent the peculiar and informal gift economy of promotional parasitism into a tailspin. File-sharing networks award both status points and downloading rights for uploads, and nothing scores so dependably as a desirable advance. There’s even a shadowy underground cabal called The Scene, populated by dedicated uploaders who lurk in the upstream canyons of data dissemination. Their efforts upset the final act of control that record companies can exert on their products, which is to tightly manage the timing of their release, allowing availability to coincide with a surge of official publicity, and thereby increasing the likelihood—so the the thinking goes—of triggering a tipping point.

These days, like everybody else working with media properties, record companies are scrambling for technological solutions to a technological convulsion whose full cultural extent is incalculable. Music makers, promoters, writers, and fans are now forced to become negotiators of the meaning of intellectual property in an era of shared and infectious data. One irritating and insufficient solution is the online, password-protected streaming link. Weee. Even more annoying are the listening parties held at corporate HQs, where a group of music writers all sit together and listen a single time to a forthcoming recording, and then shuffle home to scribble based on memory alone.

The other reigning technofix—the one employed by Ben Goldberg of Ba Da Bing—is watermarking. Because Goldberg had a lot riding on Beirut’s sophomore record, he paid the considerable—and, from what I have heard from a Rhapsody mucketymuck, unnecessarily onerous—extra cost to have his advances individually watermarked, tying each unique disc to a particular recipient. And one of these watermarked advances was stamped with my name, slipped into a plain white envelope, and sent to me, who didn’t even notice the name inscribed on the disc and therefore had no idea the advance was watermarked.

After fielding calls from Billboard and New York magazines, I of course looked for the Beirut advance, which really should have been squirreled away in that pile next to that other pile next to that box of old CDRs. I remember thinking that the record was decent if unremarkable, but that I had dug the first one so much that I needed to listen to it again before considering it a sophomore slump. But the CD was nowhere to be found.

Now there’s a lot of media at my house, too much in fact, which is why I am not only a collector but also a purger, and am probably even more neurotic about purging than about collecting. Though I carefully and constantly weed my media, sometimes my life feels so out of control that I freak out and get rid of stuff in a hasty and non-methodical matter. A couple weeks before Burning Man, when my life was pretty chaotic, I had taken a huge load of stuff to a local thrift store. No doubt there were old advances in the bag, because nobody else is interested in them and it seems more productive to give them away than to throw them away. Though I have no way of knowing for sure, I suspect that the Beirut disc slipped into that pile and was subsequently discovered by one of the Bay Area’s hipster record hounds. My bad.

But not my evil. My error was in losing track of a smart object, not in intentionally uploading a recording in order to gain status or share ratio. Publicly admitting one’s file sharing habits is kinda like talking about porn, and I’m as shy as the next guy, but one thing’s for sure: I would never upload an advance.

But Ben Goldberg didn’t know this. After giving me less than 24 hours to respond to his initial accusation—during which time I was rambling around the Black Rock desert in a fire truck with a flame thrower on the roof—the label owner went on the warpath. He sent out emails to all his publicist contacts and indy label buddies about my evil ways, and was in addition stirring up as much journalistic interest as possible, giving The Flying Club Cup a nice dose of early publicity while also being able to tar-and-feather a suddenly non-anonymous practitioner of the file-sharing arts.

I felt pretty shitty about all this. Last year I wrote extensively about Joanna Newsom’s Ys, which was famously leaked from a Pitchfork server, and I know the pain such leaks causes to artists and smaller labels alike. That said, I also know it’s not necessarily the worse thing in the life of a record, and I was pissed that Goldberg took to the wires before talking to me and trying to figure out why a 40-year-old guy who writes for righteous publications like Arthur would do something to fuck over a righteous independent label.

I called up a handful of my publicist friends, some of whom actually seemed to believe me, and eventually talked to Goldberg. I apologized, he explained his feelings, we bonded over our shared love of the Dead C. Hatchets were buried, and though I suspect my flow of advances might slow over the coming months, the prospect of being reviewed in Blender or Arthur will, in the end, keep most publicists supplying me with product—although the “product” in question will increasingly be a url. And people wonder why I mostly buy vinyl!

I would like to close with a brief meditation on the spooky, SciFi aspect of all of this. By watermarking their advance CD, Ba Da Bing was hoping not only that they would make recipients too paranoid to upload, but that the object itself would do the threatening. The physical advance, not the publicist or the label head, is now attempting to renegotiate the time-honored and rather informal promotional contract between company and writer. Such renegotiations can be aggressive, and such aggression destroys the aura of chumminess that rules between publicist and writer. One of the reasons I fucked up is that the Beirut advance did not clearly announce itself as being watermarked—my name was printed on the CD, which I didn’t even notice, and there was no further warning.

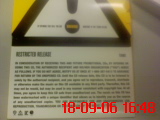

This is in stark contrast to the data grenade I recently got from Warner Brothers: a CD advance of Mark Knopfler’s shitty new record, Kill to Get Crimson. This object is a pure, time capsule-worthy artifact of the copyright anxieties of the early twenty-first century. The cardboard sleeve is yellow and black and emblazoned with an enormous exclamation point, and features the following threat:

RESTRICTED RELEASE! WATERMARKED DISC!

Do Not Copy The Music on this CD Has Been Watermarked With a Unique Identifier that Allows Us to Identify the Intended Recipient (You) as the Source of Any Unauthorized Copies.

My favorite thing here is how the text creates an addressee through the bullying use of us and you. The media organization announces that it is now an “us” acting like a data police force, and it then throws in the parenthetical second person “you” the way a cop shines a flashlight in your eyes. This “contract” creates a you that is already guilty. And you didn’t even ask for this thing to show up at your door!

On the flip side of the CD, you also find the bullshit claim that by opening the package, you are agreeing to the fat paragraph of legalese plastered below. This language includes the hilarious proviso that the CD can only be listened to by the recipient—no girlfriends, no dogs, no neighbors. When you rip open the package, you discover that bad cop has been replaced with good cop by way of a final note: Thank You for Agreeing to our Restricted Release Terms. Please Enjoy the Music!

How is anyone supposed to enjoy music after such an Orwellian negotiation! It is as if, as the loss of the physical storage medium continues to undermine the economics of the record industry, the industry is using the object to fight back. It sends humble scribes packages that speak, that has powers of command, that can manipulate behavior and—if you dare to rip it open—even grant pleasure.

Moreover, the watermarked disc itself is, in some informational sense, alive, or at least virally infected with the digital ghost of my life. When I let that Beirut advance slip out of my hands, a little piece of me went with it, a chunk of virtual identity that I hadn’t agreed for it to appropriate and that I didn’t even know about. Instead of the old informal economy of circulating copies of music, I had become enmeshed in an emerging and far more claustrophobic world of endless virtual contracts and licenses, a world where objects command and the turn against you, where music has become data, and enjoyment little more than the processing thereof.