Always Coming Home

Last February in Los Angeles, Joanna Newsom took to the stage at the ArthurBall and performed, for the first time in their entirety, the five loonnggg songs that make up her new album Ys. Many folks present were already chest-deep in the cult of Joanna, a fandom that made 2004’s The Milk-Eyed Mender a left field indie hit and turned Newsom herself into the sort of music-maker who inspires obsessive devotion as well as pleasure. At the time I admired Mender, but was, as of yet, no acolyte. I dug a handful of songs, but like many listeners, I found Newsom’s eccentric voice sometimes grating. I also feared that the outsider waif thing was just an underground pose stitched together with lacy thrift-store duds and an iPod stuffed with rips of the Carter Family and Shirley Collins.

My bad. The performance I saw that night was preternatural: a young artist stretching beyond her art towards something even more essential, simultaneously in command of her craft and caught in the headlights of her own onrushing brilliance. The song cycle she played was to Mender what, I dunno, Astral Weeks is to Blowin’ Your Mind, or what Smile is to The Beach Boys Today! She sang of meteorites and bears and ringing bells, of her and him and you, and she played not for us, it seemed, nor for herself exactly, but for the very presences her music conjured. Her songs were not performed so much as drawn from herself like nets dredged from the sea, heavy with kelp and flotsam and minnows that flashed before darting back into the deep. When she occasionally stumbled and lost her way, the material itself would pick her up again and carry her forward.

None of us standing there in that rapt crowd had ever heard music like this before. Newsom’s wild Child ballads seemed loosed from some location heretofore unseen in the realms of popular song, a secret garden lodged between folk and art music, or an unnamed island lying somehow equidistant from Ireland, Senegal, and California’s redwood coast. The music fluttered and leapt, and though there were few obvious refrains, the patterns she played circled round some magnetic core of return, at once familiar and strange. Yes she was genius. But genius has become such a throwaway word, a thumbtack of muso claptrap that marks the person rather than the source that lies behind the person. And this music was all source. And yet, it was she and not the source we heard—this charming young harper with the arresting voice and the awkward stage patter and the lacy thrift-store duds.

Sorry to keep the tankards of Kool-Aid raised high, my friends, but Newsom’s album is also pretty dang nifty: the cult disc of the decade, like the aforementioned Astral Weeks or In The Aeroplane Over the Sea. She is supported on the album by Van Dyke Parks, the sometimes Brian Wilson collaborator who feathered four of Newsom’s five songs with vivid and sprightly arrangements. The orchestration adds another dimension to Newsom’s already evocative ramble through memory and desire, a journey that goes in turns intimate and cryptic, like the alchemical meanderings of a deep dream.

Faced with music as singular as Ys, it seems almost churlish to try to pin the butterfly down. (Or is that a moth?) That said, there is no denying that the spirit of prog has moved across the face of its waters. The album, after all, has an allegorical Renaissance portrait for a cover, features oboes and French horns, and draws its odd, difficult-to-pronounce title from the Celtic folklore of France. (It sounds like ees, as in “Oui, Serge Gainsborough ees very heep.”) And indeed you must return to Van Der Graaf Generator or Trespass-era Genesis to find this sort of dramatic and, sorry, literary fit between highly wrought lyrics and the dynamics of long, intricate, tempo-twisting songs. However, I would urge you even farther back, to the great songs on the great Incredible String Band records, which also embroider earth visions onto patchwork tunes that combine heavy insights and bucolic play. For though the landscape of Ys is not particularly psychedelic, its peaks are very high, from “Emily”’s invocation of the cosmic void to “Cosmia”’s final ascent through the moonlight.

Happily for all, Newsom approaches such high-fallutin matters with a demotic American spirit and a folk fan’s love of homespun melody and pastoral grit—not to mention a canniness that makes her at once too young and too old for the truly pompous. Ys may be precious, but it is precious because the spirit behind it is rare. It does not rely on sentiment, nor does it make Great Statements. It is, rather, a Great Work: an organic but deeply intentional labor from start to finish, from the inspiration through the cover art, from the arrangements through the final, analog mixdown. Newsom gathered a stellar cast of characters around her, including Steve Albini, Jim O’ Rourke, and Van Dyke Parks, who contributes some of the best work in his career. But it is Newsom’s own visionary ambition that makes this record the very opposite of a sophomore slump. A lesser artist would have simply ridden the quirky crest of The Milk-Eyed Mender, but Newsom glimpsed a golden ring glittering on the far horizon, and she stretched beyond herself with pluck and hooked it good.

HOMESTEAD

The house that Joanna Newsom recently purchased is, well, rather Joanna Newsom. The building lies in the outskirts of Nevada City, an old mining town nestled in the western foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada range. It has a small circular driveway, rose bushes, and a broken fountain with two cherubs smeared with mud up to their necks. The one-acre property is fringed by sycamores and pines, and two massive ivy-swaddled conifers loom over the patio out back, dripping gobs of sap onto a weathered table. The firethorn bushes that cloak the breakfast nook and the porch haven’t been trimmed in a while, deranging the otherwise orderly air of a proper British cottage. Past their plump clusters of golden berries, you can glimpse her old, worn-out pedal harp, peeking through the window like a stage prop.

Newsom answers the door with a smile and invites me in. She is dressed in a knitted brown skirt, a low-cut sleeveless shirt, chocolate brown knee-high socks and moccasins. The wide leather belt tugged snug around her waist looks a lot the belt she wears in her portrait for the cover of Ys. The bangs are gone, and she’s cute as a vintage button.

“I’m sorry. I just moved in and I haven’t really been here much.” There is not much furniture beyond a couch and, alongside her harp, a gorgeous Craftsman wooden stool inlaid with turquoise. There is hand-written sheet music scattered on the floor and one large decoration waiting to be mounted on the wall, a nineteenth-century funereal display scavenged from a San Francisco thrift store. “It was there for years, and finally I had to have it.” Having spent the last few weeks obsessively listening to Ys, I can see why, so crisply does the thing reflect some of her major themes and images: inside the large glass case, two stuffed doves face off over clusters of dried wheat, neatly arranged over a fat and faded ribbon printed with condolences.

We settle down on the table outside, and dig into the past. Newsom grew up around Nevada City, but she lived for years in the Bay Area, where she studied composition and creative writing at Mills before dropping out, writing some songs and recording them with her first boyfriend, the musician and producer Noah Georgeson. Even then, she kept returning to the nest on weekends, but feared the phenomenon an old Austin friend of mine referred to as the velvet rut. “It’s a real easy place to get kind of stagnant in your head, to get overly comfortable and have the years pass by.” Now that her career has taken off and she is constantly traveling, she decided to return to the place that, in her words, makes her feel happiest and most at home.

Newsom loves her property, but what she would really like is to live on a high hill above the south fork of the Yuba river, surrounded by forests and horses and the looming lordship of the distant Sierra peaks—which is just the sort of place she was lucky enough to actually inhabit growing up. Her folks, both doctors and mildly hippyish in the manner of certain California professionals, moved up here from San Francisco in the early 1970s, to a hilltop property surrounded by vineyards and stables and dogs and chickens that wandered everywhere. At the time, the former Gold Rush hotspot was becoming a quiet center of freakdom, making it one of those rare places in American where a proximity to wild country did not mean having to live under the cowboy boot of rural conservatism. The Beat poet Gary Snyder bought land on the nearby San Juan Ridge, the minimalist composer and Pandit Pran Nath devotee Terry Riley settled down to raise a family, and spiritual communities like Ananda Village were popping up. Even one of the guys from Supertramp got a place, and built a guitar-shaped pool.

If you were standing on the back porch of the Newsom homestead, this is what you would see: “Looking out over the canyon that the Yuba river is in, you see the two sides of the canyon and then the Ridge, and behind that the higher foothills–the pass over Tahoe–and behind that the Sierra Buttes, these amazing huge mountains. We would eat outside, watching it all through dinner: insane hot pink clouds that come down and do what they do and then everything gets purpley and then the bats come out and get all drunk on bugs and bump into each other and its insane and then the lights come on and the moon comes out and reflects against the snow on the Sierras.” She pauses, recalling the scene. “It’s really pretty,” she purrs. “It’s really nice to look at.”

California’s gold country is beautiful, but it is also haunted by history. Downtown Nevada City holds onto its past with a vengeance, with zoning laws creating the atmosphere of a pleasant Miner Forty-Niner theme park. But darker and more wayward tales make their claim as well. A network of underground tunnels once linked brothels to more reputable taverns, while the Maidu Indians who called the area their home not so very long ago are tragically conspicuous in their absence. A big chunk of the hill that Newsom grew up on is fenced-off, with a nearby sign marking it simply as “Indian Burial Ground.” Newsom and her buddies never even snuck onto it. “Even when we were little there was a little bit of reverence,” she says. “We just felt really bad.” She also felt that the restive spirits and “bad juju” of the place might have caused the weird energy that seemed to descend on her childhood home in the mid-morning hours—“like there was this unbearably loud chatter but there was nothing.” Though she heard and sensed plenty of spooky shit in her house, she never saw an actual apparition there—nothing like the uncanny woman in flouncy skirts and a weird button-up collar that she glimpsed one night while working after close in Café Mecca, a Nevada City java joint that had once been a brothel. “It could’ve been a crazy Nevada City lady,” she admits. “But it is a bit of a mystery how she got through the locked door. I don’t know. I’m sort of convinced I saw a ghost.”

Such specters may be nothing more than figments in the mind, but even so, they are figments of something deep: the persistence of the past, and the layers of rich and sometimes traumatic memories that cling to buildings and rivers and burial grounds. Newsom’s music is also full of figments, of old blues blurred anew. Her famous line from “Sadie”—“This is not my tune, but it’s mine to use”—captures this twisted continuity of memory and transformation, of love and theft. Part of what makes Newsom sound “folk” is her palpable sense of such ties—not just to the foothills of the California high country, but to her family, her friends, and her harp, with its own traditions, classical and folk alike. And as her own music proves, this sense of roots does not mean theme-park conservatism or a lack of innovation—especially, perhaps, when those roots are in a rootless place like California, a restless, visionary landscape that’s always ready to crack.

HARPER

One of the most transcendent musical experiences of my life unfolded years ago during an annual folk festival held in the small Estonian town of Viljandi. A parade of slick Euro-folk-pop acts occupied the larger stages, but my wife and I preferred the informal tents, which were packed with folks dancing trad to teenage polka groups or locals playing perfectly rendered old-timey dobro tunes. As evening settled and the haze of beer fumes and burned sausage thickened, we slipped into a small whitewashed medieval church to hear the Ansambli Sistrum, an ensemble of four women who play the kannel, Estonia’s lovely version of the lap harp.

The Estonians are a Finno-Ugric folk, and in the Kalevala, the Finnish folkloric epic patched together in the nineteenth century, the great magician Väinämöinen fashions the first kannel (or kantele, in Finnish) from the jaws and teeth of a monstrous pike. The birds and the bears and all the beasts of the field come to hear Väinämöinen play the instrument, which is later lost in battle and buried at the bottom of the sea. And it seemed to me, that night, that the master musician who led the ensemble must have fished the damn thing out, because the brocade of sound she and her bad-ass crew of ice-babes plucked from their elven kannels was absolutely spellbinding: ancestral, spiky, and cosmic, like Messiaen in Middle-Earth. I was gone. Then some idiot’s cell phone went off and he gruffly took the call, right there in the church—an abrupt reminder, as if one were needed, that angels and elves do not exist in our annoyingly real world. But the spell had been real, too, or as real at least as the instruments that had briefly conjured it into being.

The instrument in question, of course, was also a kind of harp, an ancient instrument that is found in most musical cultures and is often associated with magic. Väinämöinen’s kantele is only one of a number of enchanting harps from northern climes, including the Irish chief Dagda’s ax, which, depending on the melody he played, could compel listeners to weep, giggle, or sleep. King David composed the holy psalms on a harp, while the ancient Greek culture hero Orpheus, source of the mystic Orphic mysteries and commander of the beasts, invented the harp-like lyre (one of these Greek lyres is embossed in the leather diary that forms the booklet cover for Ys). The cheesy Hollywood angels that unconsciously reverberate through our imaginations when we look or listen to harps are the cotton-candy dregs of this numinous legacy.

Though she is understandably ashamed to admit it now, Joanna Newsom was first drawn to play the harp because of the angels and fairies and other girly phantasmagoria that swirled around the instrument in her head. She was only five or so when she told her parents her desire, too young to really grapple with the instrument, but when she finally got her hands on a Celtic harp a few years later, her fascination had not abated. By high school, Newsom had switched to the more challenging and versatile pedal harp. The fantasies had fallen away, and a painstaking musical apprenticeship had begun. Though the expressive potential of the harp is in some ways hamstrung by the standard classical and Celtic repertoire, Newsom was lucky: her first teacher, Lisa Stein, taught her the basics of improvisation from the get-go. Soon the teenager was composing her own lush and melodic compositions along with practicing the usual etudes and cadenzas.

Newsom’s playing was already inventive and technically strong when the teenager met an established harper from Berkeley named Diana Stork. The two were attending a ten-day music camp held annually in the Mendocino County redwood groves—a longhaired, down-home gathering of global folk fanatics that Newsom’s mom started taking her to when she was nine. Newsom immediately distinguished herself from the other young harpers there. “You could sense she was on a real path with the harp,” says Stork, who attributes Newsom’s remarkable drive to inspiration rather than ambition. “She’s not driven by other people, or by making it, or by professionalism. The harp is what drove her, her passion and love for her instrument.”

What Stork taught Newsom was rhythm. In particular, she taught her some interlocking figures based on the kora, a stringed lute-like harp-thing made of calabash and cowhide that’s used by the wandering West African bards known as griots. Like nearly all West African music—and like essentially no classical Western music—kora music is largely polymetric, which means that each hand is following a different meter, or rhythmic pattern. The basic pattern that Stork taught Newsom is two (or four) beats against three. Stork explained that, according to the African lore she had learned, the duple measure, thumping like a heartbeat, represents the earth, while the triple time follows the breath and represents the heavens. By playing these beats against and through one another, a single performer can unite earth and sky. Said performer can also get pretty funky, because it’s the overlapping and constantly shifting slippage between the different meters that gives West African music—not to mention James Brown—that special spine-wiggling groove.

Newsom fell hard for this polymetric plucking. She loved its physicality, and the sense of substance and danceability it brought to the harp’s fragile, quietly resonating strings. She took pleasure in training her brain and hands to follow two different pulses at once, and in exploring more complex metric possibilities. Soon she began working versions of these interlocking figures into her compositions. “It was like an opportunity to do something–not new, because I didn’t make it up–but to use it in a new way.”

Newsom’s kora “bastardizations” are used to great effect throughout Ys, especially in the consoling middle passage of “Sawdust & Diamonds” (“Why the long face?”), and in the shimmering high section that follows the duet with Bill Callahan towards the end of “Only Skin.” Newsom points out that these shifting rhythms can disorient the mundane metronome in our minds, defamiliarizing our sense of where we are in a song. “That disorientation is really effective for creating something that you actually have to listen to,” says the songwriter, who has no interest in Ys becoming background music. “When any element in the musical environment is tweaked in such a way that you don’t feel like you know what’s coming next, it can cause less of a passive listening experience across the board. I like the idea of not just plodding through songs with a regular beat and a regular chord progression. Maybe the lyrics are felt or received differently, as if the listener were in a sharper mental climate.”

Newsom was keen to create this sharper mental climate because, while the lyrics on Ys can seem pretty opaque at times, they are anything but casual. On a personal level, the album is a highly focused and richly encoded reaction to a lot of heavy shit that went down in the young woman’s life, a year of mortal-coil turmoil that spun itself, through a series of uncanny coincidences, into something like a single fateful story of loss and release. This back-story not only upped Newsom’s ambitions for the lyrics, but also forced the epic length of the songs, most of which hover around ten minutes, with “Only Skin” reaching the absurd, Yes-worthy expanse of 16:53. “I needed to respond to certain things musically and lyrically,” she explains. “And I knew that I couldn’t fit any of that gracefully within a normal song length form. I thought it would be really vulgar actually, and not even worth trying.”

Luckily, Newsom already had the chops. One of the reasons that she stopped studying music at Mills was her discovery that the long and melodic instrumental pieces she was writing were more akin to traditional songs than the more explicitly experimental or conceptual compositions that are encouraged in music departments. So she opted to follow the songs. Then, with the gems from Mender under her wide leather belt, she was able to stretch out again for Ys. “I luxuriated in those new parameters,” she says. “It promoted a sort of ambition because, while I’m not making any definitive statement here, I imagine that I probably won’t do another record of long songs again. So I really wanted to do well within that format. I really wanted to do right by my topic.”

The emotional demands of Newsom’s new material also made demands on her voice—certainly the most idiosyncratic aspect of her music, and the one most likely to compel certain listeners to want to throw her CDs out the window. Newsom is a bit touchy about the press reactions to her voice, and particularly the idea that she is affecting its simultaneously weathered and childlike eccentricity. When Newsom recorded her first EPs—which she has now “officially blacklisted”—she had barely been singing at all, and Mender was recorded less than a year after that. “When I listen back to those first EPs, I’m like, well, that voice does sound fucking crazy. There is no way around it. But I know exactly what space I was in. I was so sure that I didn’t know how to sing that I was just going balls out. I was like: I’m going to sing my heart out, as crazy as it sounds, and I’m not going to care because there’s no hope of sounding anything like what people consider beautiful. I sure as hell wasn’t affecting anything. I mean, the institution of singing is inherently an affectation!”

When Newsom wrote her harp compositions, she would often score passages she could not yet play, forcing herself to strengthen her technique in order to make the music she was hearing in her head. She took a similar tack to the vocals on Ys. “There are certain passages that I literally could not sing when I wrote them,” she says. The song “Monkey & Bear”—which begins with a stack of overdubbed harmonies that sounds like the Andrew Sisters in Oz—was “basically unsingable.” But relentless touring had already improved her voice, softening its sharpness and lowering her register, and with obsessive practice she brought her throat up to snuff.

Newsom’s vocals on Ys are rich and mercurial—girlish and wizened, nurturing and needy, with Kate Bush highs and Billie Holiday lows and, yes, some trembling Björkish breaths. She seems at once to command and suffer through the tangled and shifting emotions of the songs, the rougher edges of her voice refined without losing any of their spunk. The performance reminds me of something Newsom said in 2004, when she told Arthur why Texas Gladden’s rendition of “Three Babes” had allowed her to sing. “It wasn’t just that she was from Appalachia, and that she sang in that tradition,” Newsom said. “It was that she was her. Her voice, in and of itself, is magical. And rare.” Such singularity is not easy – it must simultaneously be stumbled upon and cultivated, not disciplined so much as embraced and befriended. “My voice is not necessarily more trained,” Newsom admits. “It’s just more familiar. I inhabit it more. It’s not like this thing I’m holding out from myself. It’s a part of me.”

SONGS

The south fork of the Yuba river begins in an icy lake high in the Donner Pass, and plunges through chiseled granite outcrops and forests of fir before snaking westward above Nevada City, where the river canyons are largely protected from development. During the summer, when she’s around, Newsom visits the river every day to take a plunge and hang out with her friends. “It’s really perfect,” she says, “an amazing, life-giving, life-shaping force.” As she describes her lazy afternoons, I am reminded of why people move themselves, and their kids, to the sticks: “There’s this river with these incredible rocks and it smells so good and you just lie on them and absorb the sun and then swim in this perfect water and get out again and joke around and play and do weird silly games like walking along on the bottom of the river with a big boulder so you can stay on the bottom.” Afterwards, when evening comes, Newsom and her pals might have a barbeque or head up to a Twin Peaks-worthy steak house on the Ridge called The Willo; then they might spend the night drinking or dancing or probably both.

Rough stuff. But Newsom’s relationship with the Yuba goes deeper than such idylls. Towards the end of high school, when she was eighteen, Newsom went down alone to a wild spot along the river. After asking their assistance, she arranged some stones into a circle, and then sat down within the ring. She stayed in the circle for three days, fasting, facing the river. Her best friend and some pals camped a few miles away, bringing her water and small portions of rice while she slept. She had assigned herself things to do but abandoned them all. She just sat there and watched the river, and, even more, she listened to it.

“I was a completely different person before I went to the river, and a completely different person after,” Newsom says. When she first got back the girl was a total wreck. She would start crying when she woke up and not quit until she slept. She stopped going to school. She’d pick up the local paper, and read a headline like “Man Dies in Car Crash,” and then the crash would be in her mind, and the man’s bloody crumbled body, and his pain and dread and fearful exit from this world. “None of the calluses or borders or walls we put up to protect ourselves from going absolutely insane while experiencing life – none of those stood anymore. They had been worn completely away. I was like infantile and dysfunctional, a weepy, drunk mess.”

The Joanna Newsom who tells me this, of course, in no way resembles a dysfunctional weepy mess. She is assured and centered and gracefully goofy—not to mention whatever breed of mastermind you’d have to be to craft something like Ys. But that raw and convulsive openness is in her as well. You could say that Ys is a balance of all these forces, a marriage of keen design and crazy sensitivity, of intention and play and what she calls “skinlessness.” Like a diamond, it gleams from many sides. “Part of the intention was to send a message upwards,” says Newsom. “Another was to come to peace with certain things. Another was to find voice for this huge, gaping, wind-howling tunnel that I was looking into and just being like, FUUUCKKK. Not knowing any words for it.”

Well, she found the words. At times her songs tap into a deep well of lyric lament, the same old blues that inform John Dowland or Skip James or Nick Drake or the obscure 70s she-folkies on Numero Group’s recent Wayfaring Strangers comp. But though Newsom is a powerfully moving singer-songwriter, she is in no ways a confessional one. Ys is no diary, no sloppy heart-to-heart. Its baroque and inventive architecture, like its layers of the orchestration, act as a distancing mechanism that transmutes the emotional turbulence that inspired the work in the first place. Newsom’s language, for one thing, is intensely worked. Evocative and sometimes piercingly tender, her lyrics also reflect an almost obsessive attention to old-school poetic stuff like consonance, alliteration, prosody, and internal rhymes. In “Sawdust & Diamonds,” when she sings “mute” near “mutiny,” the words not only echo phonetically but advance the song’s themes of expression and rebellion. Later on in the song, after invoking the puppetry of romance, she introduces the image of a dove:

And the little white dove,

Made with love, made with love;

Made with glue, and a glove, and some pliers

The easy rhyme of dove and love reflects the hackneyed ease of the cliché, which she then promptly takes apart. The word glove is a splice of glue and love, held together, as it were, with pliers and glue. This wordplay is not just surface but sense: it reflects the provisional and patched-together quality that exists beneath our idealizations of love, as well as what Newsom calls the “the Frankenstein phenomenon” that emerges when that love actually creates a living being.

Newsom says that every line she wrote for the album is significant, that choosing a single word arbitrarily would have been like contaminating or physically erasing the memory of a person or a key event. That’s a high bar. At the same time, most of the specific meanings of the lyrics are locked away from the listener in Newsom’s memories or dreams or creative imagination. Those who get obsessed with these songs—and there will be many—will find that deep and repeated listening will begin to open up their voices and images, some of which Newsom admits filching from proper literature like Lolita and The Sound and the Fury. But they’ll only reverberate so far—and that’s the point. “The whole intention of making a record out of all this instead of having a conversation with a best friend is to create an artistic or musical work whose worth is completely separate from the story that I’m trying to tell.” This is the paradox of Ys: far more than most records, it tells a story, but the story it tells remains hers and hers alone.

Just as Newsom had no desire to make Ys an open book, she has no desire to turn interviews into cheesy confessionals. For one thing, she doesn’t want to strip away the rich ambiguity of the words by explaining too much about their origins. She also dreads the prospect of having a bunch of journalists asking the same questions, over and over. “That seems unbearable,” she says, pulling her hair back behind her elven ears. But the questions—and the misunderstandings—have already arrived, such as the notion that Ys is a “breakup record.” She spoke at length with Arthur partly because, besides the fact that she actually reads the rag, she hopes to lay certain matters to rest and be done with them.

“There are three specific stories on Ys, and maybe five specific characters,” she says. “There were two major losses and the knell, the ringing knell of another loss which is continuing, an illness basically.” The hammer blow that began this series of hard knocks was the sudden death of Newsom’s best friend, “one of the loves of my life.” Newsom got the call while she was driving between gigs, during the year when her career was first blowing up. “So mortality is huge on this record. And there’s more than one type of death, of course, and that’s where the turmoil of the relationship figures in, but not quite as largely as you might suppose.”

The sense of loss that overshadows “Emily” is the kind that comes to all strong families despite, or perhaps because of, their intimacy. The song is addressed to Newsom’s kid sister, who is often gallivanting about the world but came home long enough to sing on the track. “In some ways this song is a tribute to her, and in other ways it was like a plea, a letter to her about some stuff that’s happening close to home, and a reference to the fact that a lot of the little structures and kingdoms and plans we built when we were younger are just falling to fucking pieces.” The song begins with one of these imaginative kingdoms:

The meadowlark and the chim-choo-ree and the sparrow

Set to the sky in a flying spree, for the sport of the pharaoh.

A little while later, the Pharisees dragged a comb through the meadow.

Do you remember what they called up to you and me, in our window?

Meadowlarks and sparrows are songbirds, of course, but the chim-choo-ree, as far as I can tell, is probably an outgrowth of watching Mary Poppins too many times. We are in childhood, then, that weird wonderland that Newsom can invoke with her voice and the sandbox detail of some of her lyrics. Newsom has rightly complained that the “childlike” reading of her songs on Mender caused some people to take her for a naïf and to ignore the dark undertow of her lyrics. For of course it is not the innocence of the girlchild that is interesting—it is the savvy, that imaginative swagger that can inspire young girls to, say, command huge ungulate mammals around a dressage ring. (Or demand to play harps.) Here this same imagination has made toys of the pharaoh and the Pharisees, figures poached from Bible lessons, brought to life on a lazy day. But these characters are also avatars of the darker themes to come on Ys, of confinement and judgmental hypocrisy.

Emily majored in astrophysics at UC Berkeley, which helps explain all the astronomical imagery that blazes through this song and occasionally explodes into cosmic epiphany. In one of the few conventional choruses on the album, Newsom transforms technical nomenclature—the exact difference between meteorite, meteor, and meteoroid—into a wisdom teaching about the void and the relativism of perspective. Newsom’s dad is also an amateur starhound, and she remembers him teaching her, over and over again, how to find the dirt red bullet of Arcturus by following the ladle of the Big Dipper. In the song, Newsom maps these overlapping relationships—father to daughters, and Emily’s studies to her dad’s hobby—with the figure of the asterism, a technical term that describes star clusters whose borders overlap or exist within larger constellations—the Dipper, for example, is an asterism of Ursa Major, the Big Bear.

Asterism is also a twenty dollar word. I had to look it up, and most listeners won’t even bother. “I always get shit for using these big words,” Newsom admits, laughing. “And that’s valid—they can be distracting and take away from pure simple meanings. But other times they truly seem to be the only word that says the exact thing I need them to say.” Another mouthful in “Emily” is “hydrocephalitic listlessness,” which describes an image of peonies in spring, so full of water that their heads loll like the drugged. Newsom pulls off this astounding phrase—which some maniac out there has already tagged as his myspace name—with a gorgeous, lilting leap into her upper register. An allusion to a malady that afflicts someone in Newsom’s extended family, the line, like so many here, also does double-duty, evoking the album’s heavy atmosphere of saturated nature, when ripeness is all, and therefore already gone into decay. Ys is a pastoral record in many ways, but its vision of nature is as much about rot as the “fumbling green gentleness” of organic life.

Lots of images echo throughout Ys—birds, clay, borders, lights—but the most forceful is water in excess. Of course, the image of inundation is itself saturated with possible meanings—the unconscious or sex or the inevitability of change—but it doesn’t really matter because, on this record anyway, the levee definitely breaks. At the close of “Monkey & Bear,” a story-song whose animal protagonists play out a fable the sets confinement against the call of the wild, the bear Ursula flees from her monkey mate and master and swims out into the sea. In an almost shamanic process of dismemberment, she sheds her limbs and shoulders, her gut and her coat, which she then uses to catch fish that finally feed her hunger. As the music heaves in shorter and shorter bursts, the song reaches a peak of climax and apotheosis, a split moment “when bear stepped clear of bear.”

This weird catharsis clears the air for “Sawdust and Diamonds,” the one song Newsom plays without accompaniment and the one whose lyrics most amaze. Though Ys is not a breakup album, it’s fair to call “Sawdust and Diamonds” a breakup song, though one that shares few sentiments with, say, “Hit the Road Jack” or “There’s a Tear in My Beer.” Rather than express the anger or grief of the jilted, the song invents itself from the more complicated pain of one who leaves but still loves, whose heart is doubled over and turned against itself. The tension between containment and rebellion recurs, along with images that explode beyond sense with a visionary, dreamlike power—a bell falling down white stairs, a belfry burning sky-high, a pair of marionettes that couple before an admiring audience. In the end, the song is not about couples per se but the forces that move them, for good and ill. “You would have seen me through / But I could not undo that desire,” Newsom sings over an aching repeated arpeggio. Then she turns and addresses her desire directly, repeating the word with a plaintive ferocity that’s both resigned and supplicant.

“Only Skin” is the longest, most obscure, and least shapely of the album’s songs, the one that detractors will most readily point to as evidence of Newsom’s art-rock self-indulgence. I’ve listened to it tons, and it’s grown on me, and the peaks are worth the valleys. It was the last song she wrote, and the one where, perhaps foolishly, she attempted to weave together all the various threads and “ghost characters” in her tale. “It was an attempt to encapsulate everything, and to find some measure of grace.” In her 2004 Arthur interview, Newsom described her patchwork method of writing songs: “I have little objects and every once in a while I take them out of my pockets, lay them all in a row and I like the way they look next to each other, so that’s a song!” Here the row of items goes on for pages. Most revealing, perhaps, is Newsom’s admission that the last few verses of the song—where the long-suffering female protagonist promises to do right by her darling—are the only place in the whole album where she just made stuff up, where the song steps away from poetic autobiography. “I was hoping for a good resolution, but I felt helpless and foundering at the end. And so I reached for this fiction, because I didn’t know how to end the song in full truth. Otherwise, it would go on forever.”

Ys ends where the story began: with the death of Newsom’s best friend. “Cosmia” is a composed rather than wrenching elegy, and the most conventionally structured of the five songs. The engulfing waters of the rest of the album are here channeled into a river, a site of solitude and communion. In the long line of beasts and critters that inhabit the rest the record—meadowlarks and monkeys and horses and hens—here Newsom calls in the moth, the final form of what William Blake called “animal forms of wisdom.” After the singer gets the devastating news, she walks into a cornfield, and moths almost drown her. Later, she invokes the classic image of moths immolating themselves in the artificial sun of a porch-light—those attractive but dubious goals towards which so many of us so readily plunge. But here wild Cosmia, her form a thing of water and fire, flutters off on a farther flight, towards the possibility of a “true light” that might even shine back down here, when the night comes in.

Like the whole record, “Cosmia” affirms life without offering a wisp of false consolation. “The thing that I was experiencing and dwelling on the entire time is that there are so many things that are not OK and that will never be OK again,” says Newsom. “But there’s also so many things that are OK and good that sometimes it makes you crumple over with being alive. We are allowed such an insane depth of beauty and enjoyment in this lifetime. It’s what my dad talks about sometimes. He says the only way that he knows there’s a God is that there’s so much gratuitous joy in this life. And that’s his only proof. There’s so many joys that do not assist in the propagation of the race or self-preservation. There’s no point whatsoever. They are so excessively, mind-bogglingly joy-producing that they distract from the very functions that are supposed to promote human life. They can leave you stupefied, monastic, not productive in any way, shape or form. And those joys are there and they are unflagging and they are ever-growing. And still there are these things that you will never be able to feel OK about–unbearably awful, sad, ugly, unfair things.”

We are getting near the heart of things, and so I ask her, wondering myself, if you can experience such gratuitous joy without the trauma of skinlessness.

“Maybe not. It’s possible that if you are not open to one of those experiences you can’t be open to the other. It requires a sloughing off of a particular sort of emotional callous, and you’re probably shedding the same block, the same blunting mechanism in terms of joy and in terms of sorrow. And maybe you go through a million regenerations of that in your lifetime, feeling very blunted, and then feeling very exposed and over sensitive.”

“So where are you now?”

“I may be rewarding myself with a nice long numbing bath,” she laughs.

ARRANGING

Newsom is an impressively late riser, and though I showed up at three she still hasn’t had her coffee. So she pulls on a brown knit cap and we bundle into her dusty Suburu Forester and head towards Ike’s Quarter Café, a neo-creole joint in downtown Nevada City. Over the gorgeous, elegiac folk sounds of the forthcoming P.G. Six record, she talks about how clumsy and disorganized she can be, especially when she’s performing. She invariably spills water on herself, and once slipped in a puddle of beer at the Swedish American Hall and landed on her ass smack-dab in front of the audience, ripping her dress. “I’m eternally indebted to any journalist who was there because not a single person mentioned the incident.”

We arrive at Ike’s and settle in to an outdoor booth shaded by vines and trellises. Newsom’s speaking voice is almost as variable as her singing one, and when we place our orders, as when she says “please” or “thanks” or “hello”, the boopsy factor goes up a notch, which is particularly amusing when the order in question is a medium-rare cheeseburger with bacon and a side of horseradish cream. Though a strict vegetarian for years, Newsom is clearly one no longer, and as a fellow veggie backslider, I relax. (Both of us, it turns out, started eating meat again after having carnivorous dreams.) She wants to go hunting sometime with her uncle Dave, who occasionally makes the cover of hunting and fishing magazines and likes to bag wild turkeys in the area. “But I’m pretty sure that when it came down to the wire it would be too difficult for me emotionally, which makes me feel like a huge hypocrite.”

Hypocrite or not, Newsom is capable of eating steak everyday when she is on tour, just to ground herself amidst the chaos. “I’m not a good traveler,” she says. “If I wasn’t touring I would probably almost never travel. On tour, I just get so drained and bonkers and fragile. Totally cuckoo. Very small things seem insurmountable.”

Things go much better when she travels with people she digs, like when her friend Jamie accompanies her on tour, or the time Newsom took a road trip with her boyfriend Bill, just as she was thinking about how to shape her new songs into an album. Bill is Bill “Smog” Callahan, a Drag City label mate who met Newsom on tour. (She made a guest appearance on his 2005 record A River Ain’t Too Much To Love.) For the trip Callahan bought Newsom a copy of Song Cycle, which Van Dyke Parks released in 1968, when the musician was just about Newsom’s age. Parks is best known for collaborating with Brian Wilson on the lyrics for Smile, but his single greatest work remains this art-pop head-trip through the American musical landscape. Newsom listened to it for three days straight. She was already thinking about fleshing out her songs with orchestral arrangements, and told her fella that she wanted to work with someone who scores like Van Dyke Parks. “Well, perhaps you should ask Van Dyke Actual Parks,” he said.

So she did. The couple were already heading towards Los Angeles, and Drag City arranged for her and a harp and Mr. and Mrs. Parks to all meet up in a hotel room, where Newsom played him all give songs in one fell swoop. Newsom was hoping he’d agree to score one song, but Parks told her he wanted to take on the whole thing.

Parks may not have known what he was getting himself into. Newsom knows what she wants musically and is not shy about saying it. Of all of Parks’ initial arrangements, only the score for “Monkey & Bear” worked for her out out of the gate—which is perhaps not surprising, given that Parks’ first paying gig in Hollywood was scoring “Bear Necessities” for Disney’s Jungle Book. But all the other arrangements required an exhaustive back and forth between Newsom and Parks; even then, none of the arrangements for “Stardust & Diamonds” ever felt right, which is why Newsom decided to leave the song unadorned, an intimate clearing in the midst of a forest of sounds. After half of year of working remotely on their shared vision, Newsom went to Parks’ home studio in LA to sift through the final written score bar by bar. “He’d leave the room to go to cook his family dinner and I would just in there combing through everything.”

“I’ve never had a bigger challenge,” Parks told the webzine Bandoppler about working with Newsom. “Or more joy in discovery.” You can certainly hear the joy. In “Emily,” which features his most innovative contribution to the album, the orchestration both echoes and tickles the lyrics – a long minor chord follows her mention of shadows, while a goofy banjo appears when she sings about her pa. One point of friction that occurred during the recording sessions was Parks’ desire to add electric bass and electric guitar. “I was like Hellll no,” Newsom says. But Parks, who also contributed accordion to the album, went ahead and called in two great session players of the old school, Grant Geissman and Lee Sklar. “What they added was unbelievably important and grounding,” Newsom says. “I’m so glad that Van Dyke insisted on that.” Another bone of contention was Newsom’s insistence on recording the orchestra to analog tape, something that has probably not been done in LA since the Rodney King riots. Newsom always wanted an all-analog project, and rehearsed the familiar arguments with Parks: analog recordings capture more information than digital, and are richer and warmer-sounding to boot. Parks agreed with her, but also pointed out that analog was a pain in the ass. Newsom kept on it, though, and eventually got her way. “It was definitely difficult but a lot of the difficulties weren’t things I, um, had to personally deal with.”

I asked Newsom why she was so insistent about analog. “Just instinct,” she says, her green eyes lighting up. “I just thought it would be so rad to do a fully analog all-orchestral recording. It would be so incredible to be get to hear the vinyl version and put that out there. That was the dream driving me the whole time.”

ANALOG

The hoary debate over analog vs. digital recording usually grinds through its fated moves over issues of technical fidelity and sensual perceptions like “warmth” and “sharpness.” But the wrangle also has a more intangible dimension, one that’s emotional, cultural, almost metaphysical. Analog and digital aren’t just different ways of handling sound – they are different metaphors about how we mirror and model the world. The term analog comes from analogy—the undulating grooves on your vinyl LP (and, more complexly, the magnetic fields captured and reproduced by the metal filings on magnetic tape) are very much like the material undulations of sound waves in the air. Digital comes from digit: an abstract numerical representation of a single slice of flowing sound, sampled at such a rate as to closely approximate a continuous wave. Analog hugs more tightly to the ways of the earth, with its flows and inevitable physical decay. Digital, which hypes the eternal life of the perfect copy, tends to dematerialize and disincarnate—just compare an MP3 or DJ software to an old 78 or a pedal harp. Faced with the dominant empire of the digital, some people don’t just choose to make or listen to more analog recordings. They choose to live more analog lives.

Take, for example, one Joanna Newsom, who was born two years before the first Macintosh appeared and has followed up her Ike’s cheeseburger with a pint of Anderson Valley ale. She owns a computer but doesn’t get the Internet at her house and has to take it to a café for email. She uses the machine to make CD mixes for friends, but never plays music from it. She doesn’t own an MP3 player. When Newsom moved into her new house, she noticed the perfect spot for a CD player, which she had never owned. But she opted against it. (She does play CDs in her car.) “I decided that a good choice as far as sanity goes was to just have analog sounds in the house. I do have a digital camera and I’m fine with that. But sound affects the brain and the mood so much. It seemed like a good thing to just rule out any possibility of a crispy mosquito of digital sound boring into your brain. Just rule it out of the home environment.”

Newsom learned a lot about listening to music from her boyfriend Bill, for whom vinyl recordings are as much an invitation as a storage medium. “The way he listens to music is one of the most endearing and sweet things I’ve ever seen,” she says, taking a sip of her beer. “He takes off his shoes, sets them down and gets comfortable. He kneels or sits in front of the record player, lifts the cover, reverently chooses a record, puts it on, closes the cover and just listens, start to finish. Whenever I go to see him and we listen to music like that, I register in myself how much better it feels than other ways of listening, which are like rushing to eat a meal because you’re super-hungry. You need to eat, just like you need to listen to music, but it never feels good if you do it like that. So I am trying to set my life up in a way where I don’t have to listen to music anyway other than putting on a record and sitting and listening.”

Newsom recorded her own performance for Ys with Steve Albini, who has recorded thousands of musicians and works strictly with analog. (Albini once offered this thunderous prophecy on the back of his old band Big Black’s Songs About Fucking: “the future belongs to the analog loyalists. fuck digital.”) Albini and Newsom met at LA’s slick Village Recording Studios, where Todd Rundgren was recording Meatloaf in the studio next door. Still, Albini had to go through five tape machines before getting one to work, and that one he had to fix himself. “It was a really embarrassing scenario,” says Albini. “Its not like we were in some cheap-shit chop shop. I’ve made records in people’s living rooms that went better from a technical standpoint.” Once he cobbled together a studio, Albini then faced the challenge of recording the harp. “It’s a quiet instrument. It doesn’t excite the room much, so you have to work close to it, but because it’s physically large you can’t just stick a mic up close to it.” Albini wound up placing four small Crown GLM mics, which are about the size of a kitchen match, along the instrument’s resonating belly. A nearby mic picked up the stereo image of Newsom playing, and a distant mic picked up the reverberant sound of the room. “It was fun,” says Albini, who enjoyed working with Newsom, a woman he describes simply as “bad ass.”

The album was mixed by another analog enthusiast, the guitarist and producer Jim O’Rourke. The mixdown took place at New York’s Sear Sound, a legendary shrine to analog recording run by Walter Sear, a Joe Meeks-like figure who once sold synths with Robert Moog. This is what Newsom told O’Rourke she wanted: “I want the vocal and harp performances to feel central and grounded and close and intimate and still, as though they are taking place in a small space very close to the listener. I want the orchestra to feel hallucinatory and constantly shifting in space and I want it to be mixed in a way that relates to the story being told and the lyrics and the mood very closely.” After slaving two 24-track machines together to accommodate all the tracks, O’Rourke did a rough mix by instinct before returning for detail work. He methodically went through each track, following it from beginning to end with a flying fader, constantly modulating, creating an ever-changing landscape of sound that accorded with the shifts and undulations of the songs. He also cut out sections of Van Dyke Parks’ arrangements, arguing that the gorgeous details that the arranger and Newsom had so painstakingly worked out were not always in service to the songs, which sometimes demanded greater intimacy. Everyone knew that Parks’ arrangements might be cut back in the mix, but they worked hard to find the right balance. “Hopefully he’s happy with the results,” says Newsom.

One day at the studio, O’Rourke told Newsom he had a vision for an ad for the record. “It’s just a picture of you. Above it says Music, and below it says Is Back.” O’Rourke was not kissing ass. In an email, he wrote that Newsom’s record recalled and confirmed why he fell in love with music in the first place. “It’s someone’s vision seen all the way through–sweat lost, brain racked, soul searched, and fingers calloused. I doubt we’ll hear anything as brilliant in a long, long time.”

After Ys was mastered at Abbey Road and chopped into digital bits, advance CDs were, as usual, sent out to music scribes. Newsom expected that the record would leak onto the Net, an inevitable phenomenon and not necessarily a bad one. But Ys did not leak—it surged through a broken dam. For reasons that remain unclear, the album wound up on the public download server of the indie taste-maker Pitchfork. Because the leak itself was newsworthy, or at least gossip-worthy, a certain category of websites—a category whose loathsome name begins with “b” and rhymes with slog and bog—went apeshit. The word (and the downloads) spread through muso sites and beyond, to places that would normally not give a fig for Ms. Joanna Newsom, who, needless to say, was not particularly pleased.

Newsom had exerted her creative control throughout the entire creation of the album, and now she had lost it. Though Ys probably gained more in publicity than it lost in future sales, that didn’t matter to the artist, who is a quality-over-quantity gal, and does not really cotton to such a calculus. She wants her album to be taken whole, as the old-school Album it is: a thematic and developmental sequence of songs wrapped up in a nifty package with a gorgeous cover, a beautifully-designed booklet for lyrics, and, ideally, a nice big gatefold sleeve. “I want anyone who has the record to feel like it’s this little object of some worth or substance,” she says. “So much stuff is throwaway nowadays and I wanted it to not feel that way. Ironically, of course, it leaked on the Internet, which is like the epitome of throwaway, or at least intangibility.” Indeed, there was something almost mythic about the whole affair. It was as if the archons of the digital needed to visibly humiliate Newsom, with her brazen and well-publicized invocation of the old ways.

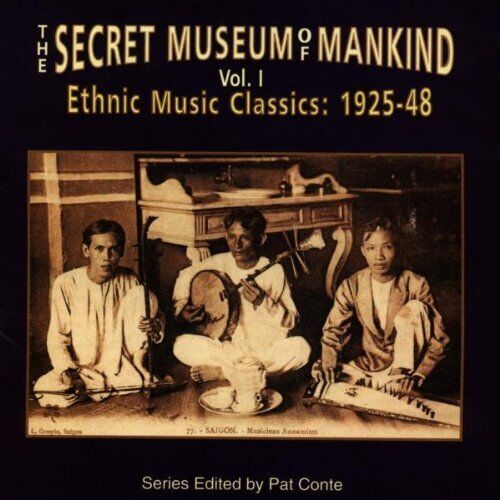

PORTRAIT

A week before I met Newsom, when I was trawling Joanna fansites for bootlegs, I sampled some of the chatter about Ys and discovered that the most controversial aspect of the album by far was the cover portrait of Newsom. Some bitched about the “Ren Faire costume,” and others compared the image to the cover of a fantasy novel. These reactions are understandable but still pretty lame. A great Album requires a great cover, and Benjamin Vierling’s painting—which looks like a Dürer by way of Millais, but more pop-surrealist—is pretty great. Luminescent, esoteric, and vividly detailed, it mirrors Newsom’s moodier new material as much as the strange and playful embroidery of Emily Prince’s cover complemented Mender.

In the portrait, Newsom sits stiffly in an old oak chair, wearing a plain brown maiden’s dress, a broad leather belt, and a wreath of wheat and flowers in her loosely braided hair. She is framed by a horse skull, a blackbird, and more flowers, some of which—like the poppy in her hair and the morning glories surrounding her chair—are visionary plants. The color of the morning glories, which are somehow growing out of the floorboards, echoes the hues of the sky. The outside is within, they seem to say, just as the ordered, formal composition is fringed with wildness. But the symbolic heart of the painting lies in Newsom’s hands. Like the skull on the wall, the nicked sickle in her left hand is a memento mori, a reminder of death, its lunar shape echoed by the airplane contrail in the sky, another image of impermanence. In her right hand, she holds a framed and mounted specimen of the order Lepidoptera. At first I took the critter to be a butterfly, which made sense, if for no other reason than the fact that Newsom loves Nabokov. The butterfly also represents the transformative emergence from a death-like state, and is a traditional symbol of the soul (the Greek word psyche, or soul, also means butterfly). But after a round of late-night Google searching, I finally discovered that the thing is actually a moth—a Cosmia moth, to be exact, pinned and framed and protected, after a fashion, from the ravages of time.

I want to see this painting in all its original glory, and so, after Newsom and I finish our Solstice ales, we drive over to Vierling’s studio in downtown Grass Valley, which lies close to Nevada City. We arrive at St. Joseph’s Hall, a ramshackle former convent and orphanage now given over to artist studios and the occasional concert. Climbing the shadowy exterior stairwell, I am not surprised to hear from Newsom that this place too is haunted.

Vierling’s small studio is orderly and calm, and the 31-year-old man, who Newsom pegs as an “old soul,” is thoughtful, friendly and gently reserved. The Newsom portrait is radiant. Its luminosity and juicy detail are the result of a laborious and exacting process of applying alternate layers of egg tempera and oil, an old-school technique that took Vierling six months to execute. Too eclectic to call himself a true traditionalist, Vierling is most directly inspired by the Nazarenes, a nineteenth-century group of German mystical painters who rejected the mannered styles of their day and looked back to medieval and early Renaissance models. As Vierling wrote in an email, “The Nazarenes glorified medieval art because it embodied a paradox: the perfection of the ideal as God intended, in contrast with the entropic negation that all matter is subject to.” This attitude—which Vierling rightly says is more Gnostic than Catholic—influences his own dogma-free approach to sacred art. “I believe that a painting has the ability to reflect back to the viewer the image of what exists behind the subject, the spirit behind Matter if you will. It is my goal to reveal what is eternal in the subject, be it an object or a person.”

Vierling did not paint Newsom’s face from life or from a photograph, but from an image in his mind he constructed after studying scores of photographs taken of the singer from various angles. Some fans have complained that the portrait does not really resemble Newsom, but having spent half a day with her, I would counter that her face itself is mercurial. (And, except for the wreathe, she is certainly not wearing a costume.) The painting’s most excellent likeness, though, are Newsom’s hands, which are also Vierling’s favorite part of the picture. They are strong and lovely and articulate. Like the music on Ys, Vierling’s rendering brings together an expressive, spiritual exuberance with an almost clinical execution of detail and technique. That tempered balance is the key. “The alchemists called it the Magnum Opus, the great work,” wrote Vierling. “I call it a painting. It might just as well be a song, a verse, or even digital code. It is what you invest into in, nothing more or less.”

MYTH

The last element of Newsom’s magnum opus to arrive was its title. Newsom spent a long time fishing for a name that would encapsulate the spirit of the project. One night she dreamed about the title, a swirling reverie that featured the letters Y and S smashing together in unusual combinations. Afterwards she began searching for a single-syllable word that bluntly combined the two letters. At the same time, Newsom also finally got around to reading the fantasy novel on her nightstand, which happened to be her best friend’s favorite book. She thought the novel might be cheesy, but she loved it. And one night, there it was: a passage about a seaside castle that had been raised “by the magic of the ancient folk of Ys.”

Et voila–Newsom had found her title. Ys is a lost city immortalized in the folklore of Brittany, a region that lies along the northwest coast of France. As Newsom read more deeply into the legend, things got a little spookier. Here, in a nutshell, is one version of the tale: Dahut, the blond daughter of King Gradlon, begs her father to build her a citadel by the sea. And so he does, creating a city that’s protected from the waves by an enormous wall of stone whose one entrance, a gigantic bronze door, is opened by a key that Gradlon carries around his neck. Like a lot of seaside towns, Ys attracts horny sailors laden with goods, and Dahut makes a wicked pact with the powers of the ocean to make the already decadent city rich. The agreement is rather kinky: every night the princess takes a new sailor as a lover, and places a black mask on his head. In the morning, when the song of the meadowlark is heard, the mask strangles the guy, whose body is then offered to the waves. Eventually Dahut meets her match: a haughty crimson-clad lover who persuades her to slip the key from around the neck of her sleeping father. The rake then opens the gates of Ys to the raging ocean, which swallows the city. Father and daughter escape on a magic steed, but daddy is forced to drop the princess into the sea and she drowns. In some tellings, she is then transformed into a mermaid.

Newsom saw so many parallels between this story and her own that it freaked her out. There were the themes of decadence and excess, of fathers and daughters and boundaries burst, not to mention details like the meadowlark and the heroine’s underwater metamorphosis. Then Newsom stumbled across the clincher: according to Breton folklore, on calm days along the coast you can hear the sunken bell of the cathedral of Ys, tolling evermore. Later, as Newsom finished the fantasy novel, she stumbled across yet another uncanny echo of her own tale: a line that spoke of “that damnable bell,” a direct sample, as it were, from “Sawdust & Diamonds.”

“To me that seemed like the craziest coincidence,” says Newsom. “It seemed like a confirmation, a chiming confirmation, that all was at it should be.” Such synchronicities had ghosted her throughout the project, as the interwoven stories of her convulsive year became even more bound together in her lyrical retelling of them. That, of course, is one of the gifts of the creative imagination: a sort of gratuitous grace that can shelter us from the gaping sky, an excess of meaning that is capable of redeeming the mess we’re in without denying how fucked up it is. Many of us have sensed a secret logic working through our lives, and at first Newsom resisted it.

“I fought angrily against seeing particular types of poetic organization because it seemed awful to see my own life and these actual events in that way. But when you put forth an intention into the universe to speak a certain truth and narrate a certain period of your life, you start to see the sorts of symmetries that you are not usually supposed to be able to see until you are on your deathbed and your life flashes before your eyes. And you see exactly why everything happened. And even the most painful things you’ve ever been through can seem unbearably beautiful.”

My absurdly long profile and cover story on Joanna Newsom and her record Ys, from Arthur 25