Anarchists, beer, and the man in the moon

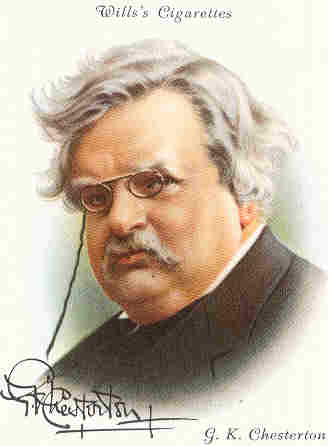

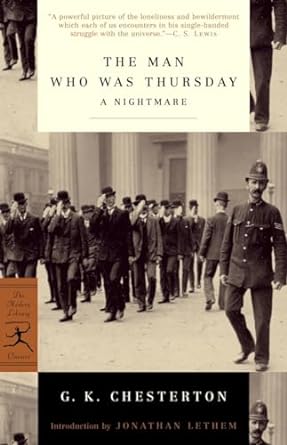

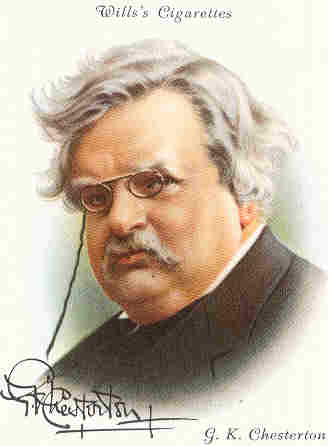

Prompted by Adam Gopnik’s insightful if somewhat troubled New Yorker profile of the great (and enormous) G.K. Chesterton, and my own recent return, with enormous pleasure, to the Victorian/Edwardian fantasy fiction of Machen, Kipling, and Robert Louis Stevenson, I finally sat down and gobbled up Chesterton’s classic metaphysical and political romp, The Man Who Was Thursday. And what a romp it was—a cheery antimodern screed wrapped up in a Kafkaesque detective yarn disguised as a slapstick cartoon and topped with a colorful and vaguely heretical Christian allegory that somehow made this heathen feel genuinely good about the world.

The story concerns Syme: a “philosophical policeman” on the hunt for bomb-chucking modern nihilists. Masquerading as a poet, he goes undercover and brazenly joins the Central Anarchist Council as it prepares to, well, start chucking some bombs. But Syme enters a hall of mirrors: black masks and secret chambers, sword duels and balloons, double-crossers and reality-bending upwellings of his own fears and fantasies—all of it lorded over by the Council’s evil but charismatic President, the unnerving (and also enormous) Sunday, who has the dark and uncanny presence of the Judge in Blood Meridian and at the end of this dizzying novel turns out to be none other than…well, let’s just a say a personage rather higher up a cosmic hierarchy that is not run on the usual black-and-white lines. At the end of the book all the twisted reflections that have faced Syme line up into a consonant crystal chord the reaffirms, in a weird way, old school values in the face of all manner of modern noise—Nietzschean nihilism, poetic poofery, airless science, political revolt. And yet it does so in a deeply modern manner that makes this book still resonate today.

Not nearly horrifying enough to deserve the “nightmare” subhead Chesterton himself gave it, The Man Who Was Thursday is a peculiar genre mashup, a delirious transition between classic fairytale fantasy, cops’n’robbers action, and the grimmer labyrinths of modernist alienation. At one point, Syme glimpses a huge and very new modern tenement building by the side of the Thames, which looks to him like “a Tower of Babel with a hundred eyes,” a mythic tower he compares to a dream. Later, Syme climbs the same building to meet the anarchist Dr. Bull, who never removes his dark glasses (the mirrored shades of the day). But now the mythopoetic frame is replaced by austere science-fiction. “As he now went up the weary and perpetual steps, he was daunted and bewildered by their almost infinite series. But it was not the hot horror of a dream or of anything that might be exaggeration or delusion. Their infinity was more like the empty infinity of arithmetic…like the stunning statements of astronomy about the distance of the fixed stars.”

With Syme’s continual forays into major 20th century feelings—paranoia, absurdity, a pervasive sense of unreality, even the decomposition of representation initiated by Impressionism—we can see Chesterton glimpse the future, of both genre writing and a century dominated by violence, technology, and the culture riot of nihilism. But in the face of this, Chesterton cheerily and in some ways acutely reasserts the traditional force of the imagination and its confident central image of ordinary humanity. “Even the most dehumanized modern fantasies depend on some older and simpler figure; the adventures may be mad, but the adventurer must be sane.” In other words, to hold to the root of fantasy, that childhood wonder that CS Lewis felt was the key to Christianity, is also to hold to the human. “To Syme’s exaggerative mind the bright, bleak houses and terraces by the Thames looked as empty as the mountains of the moon. But even the moon is only poetical because there is a man in the moon.” As we continue our plunge into the maw of the posthuman, my friends, we would do well to remember this: that the human we may want to protect is not a rational ethical agent grounded in institutions and law, but a form of imagination—perhaps, if certain esoteric and western mystery traditions are correct, the key form.

This year is the centennial of The Man Who Was Thursday, and my Modern Library edition features a swell introduction by Jonathan Lethem. He says great things about Chesterton’s characterizations of ideas—the way he fleshes out these walking concepts so that they cease being allegories without quite becoming characters. Lethem also astutely places the novel halfway between Conrad’s Secret Agent and Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, both also published around 1908. At the same time, while the tangles of Chesterton’s plot are philosophical and political tangles, the narrative feels like a fable, at least in the way that Kafka feels like a fable, with various worldviews and dream figures appearing as so many charming and cartoonish characters, simultaneously foolish and appealing, while meanwhile the instability in reality ebbs and flows.

Chesterton is a conservative romantic and, over his life, an increasingly fervent Catholic defender of the imagination. Here is Gopnik, writing on two of Chesterton’s major themes:

First, the quarrel between storytelling, fiction, and reality is misdrawn as a series of illusions that we outgrow, or myths that we deny, when it is a sequence of stories that we inhabit. The second is not that small is beautiful but that the beautiful is always small, that we cannot have a clear picture in white light of abstractions, but only of a row of houses at a certain time of day, and that we go wrong when we extend our loyalties to things much larger than a puppet theatre. (And this, in turn, is fine, because the puppet theatre contains the world.)

Chesterton was also acute about politics. He was deeply concerned with the erosion of local values and the intimate scale of a proper human life at the expanding hands of global capitalism and its cousin international socialism, and therefore distrusted the intellectual cosmopolitan culture of trendy nihilism that is represented in Thursday by anarchism. (As Gopnik points out, anarchism was as major a bugaboo for the Edwardians as terrorism is for us.) Of course, as Chesterton suspected, the revolutionary anarchists turned out to be the global capitalists after all, and the rending of our lifeworlds has now reached an insane accelerando. The world that disturbed him has come to pass and it is, as he foresaw, no utopia. But he also saw, and sympathized with, the forms of thought and consciousness that would attend this transformation. There are many moments in Thursday where I felt he was making allusions to my own states of mind, and than dodging back to his own pleasant leafy land. Even as he mocks much that moderns might find attractive, or at least incontrovertible—from the “airless vacuum” of science to Buddhist doubt to paganish hedonism to proto-existential despair—his characterizations are affable and resonant, mocking but somehow sipping from the same well. He has none of that nastiness so pervasive among even funny and penetrating conservatives.

That said, you know that a lot of Chesterton’s pals would be a total drag to hang out with, and that the man’s core sympathies not only raise at least as many problems as the forces he attacks, but are often odious when stated baldly. This is the challenge that Chesterton holds out to those of us who love his sentences, his earthy sympathies, his acute and playful way of thinking through paradox and parallelism (not unlike Zizek, actually, who appreciates that Chesterton is well worthy of a Hegelian wrestling match in this great if chewy article.). Looking beyond Thursday to Chesterton’s apologetic classics like Orthodoxy and St. Francis, how do we—leaving aside the definition of this we purposefully slippery, for we too may be, at times, Christians and pagans and skeptics alike—deal with Chesterton’s intransigent and sometimes irritatingly sentimental Roman orthodoxy, so central to his vision, or the creepy crap that almost inevitably hangs about such old school antimodernism? Gopnik, for example, makes much of Chesterton’s anti-Semitism—too much, I’d say, not because anti-Semitism is pretty, but because we all know that anti-Semitism is not pretty, and that its push-button power as a criticism makes it too easy for readers to simply write off Chesterton as some blustery kook when they owe it to themselves to take on the complexities of his literally wonderful brand of reaction.

I think the simplest answer to this problem is the Chestertonian one. Without wavering in your core commitments, whether they be a rejection of spiritual authoritarianism or a (perhaps torn and frayed) belief that relativism is not as corrosive as the fat man feared, can you approach Chesterton with the amused sympathy, the respect, and the willingness to wrestle with which he approaches the reprobates? Chesterton is enormously charitable. He engages, he remains open and amused, even if he guards his pearl of faith and commitment in a closed shell of obedience. The way a great novelist (which Chesterton is not) can get inside of characters, Chesterton can get inside of worldviews: nihilism, moral anarchy, heathen lusts, and the understandable desire to throw bombs at heads of state. Can we similarly engage Chesterton?

After all, for all his universal orthodoxy, Chesterton’s God is also the God of the local and the ordinary. Chesterton’s religion is of a piece with his love of the corner pub and a side of beef and a chat with the dairy farmer over ale. This is not only a congenial Christianity but, in our days, an increasingly noble stance, as it becomes clear, to some of us anyway, that sanity cannot be had without an intense imaginative and practical re-engagement with the local, albeit a local far more mixed and inhomogeneous that Chesterton has the strength or temperament to imagine. I don’t know about you, but I am pretty weary of the call of the global—the rhetoric of farflung networks, of mashup culture, of the mastering tongues of science, of abstract flows and international conferences and the disincarnating vampires of cell phones and laptops and PDAs. Chesterton could sense this coming, but it doesn’t seem to bother him much. He just sits there with a warm smile, limning the spooky thrills of our tangled, provisional, and anxious predicament, and then inviting us back into the pub to share a pint of ordinary wonder.