Establishing the Alembic

Last year two meditation nerds named Michael Taft and Kati Devaney invited me to help them start a new center in Berkeley. Michael is a popular no-bullshit meditation teacher and the host of the laser-sharp Deconstructing Yourself podcast, which I appeared on shortly before we became friends. Kati is a brilliant and friendly Phishhead who was rocketing up the professional neuroscience ladder before she abandoned academe to be boots on the ground for this crazy project.

I am not much of an institution guy, but I also like to try new things, and the time and place and the invitees were right. Despite the challenge of getting people together “post”-pandemic, we all feel that now is the time, in the Bay and in the world, to re-energize actual places — architectures of presence and possibility where bodies mingle, selves are stretched, communities cohere, and serendipities go down. Though we are still honing the elevator pitch, I have been describing the project as a center for meditation, movement, citizen neuroscience, and visionary culture. Inspired by Western esotericism and Southern shamanism as much as Eastern contemplative traditions, we decided to call out the transformative alchemy of the thing by naming it the Alembic.

The space itself, a former yoga studio and the site of some legendary sacred fetes, is beautiful, and the variety of its half dozen rooms embodies one of our overarching, and possibly foolhardy, goals: genuine pluralism. In the spirit of an open curiosity far too rare these days, we aim to curate an authentically diverse range of practices, perspectives, and modalities inspired by the old Esalen principal that in the territory of awakening no one captures the flag. In other words, we are committed to flying a patchwork flag, to balancing the woolly weirdness with skeptical error-correction, and to set our cult detectors on high. To crib Michael Taft’s opening spiel for Deconstructing Yourself, it is a place for metamodern mutants.

So far we have had classes and workshops on Chöd, ecstatic dancing, liminal dreaming, breathwork, relational meditation; we’ve hosted groovy parties, a Halloween Death Sangha gathering, and a recurring integration-through-art workshop called “Alligator Lizards in the Air.” We are talking to Platonists and pagans, coders and astrologers — last Saturday night a metta group meditation bloomed into an EDM get-down. The place is a cauldron, and we haven’t even gotten our brain scanning gear lined up.

For the moment, the Alembic calendar is on our Eventbrite page.

Flashback

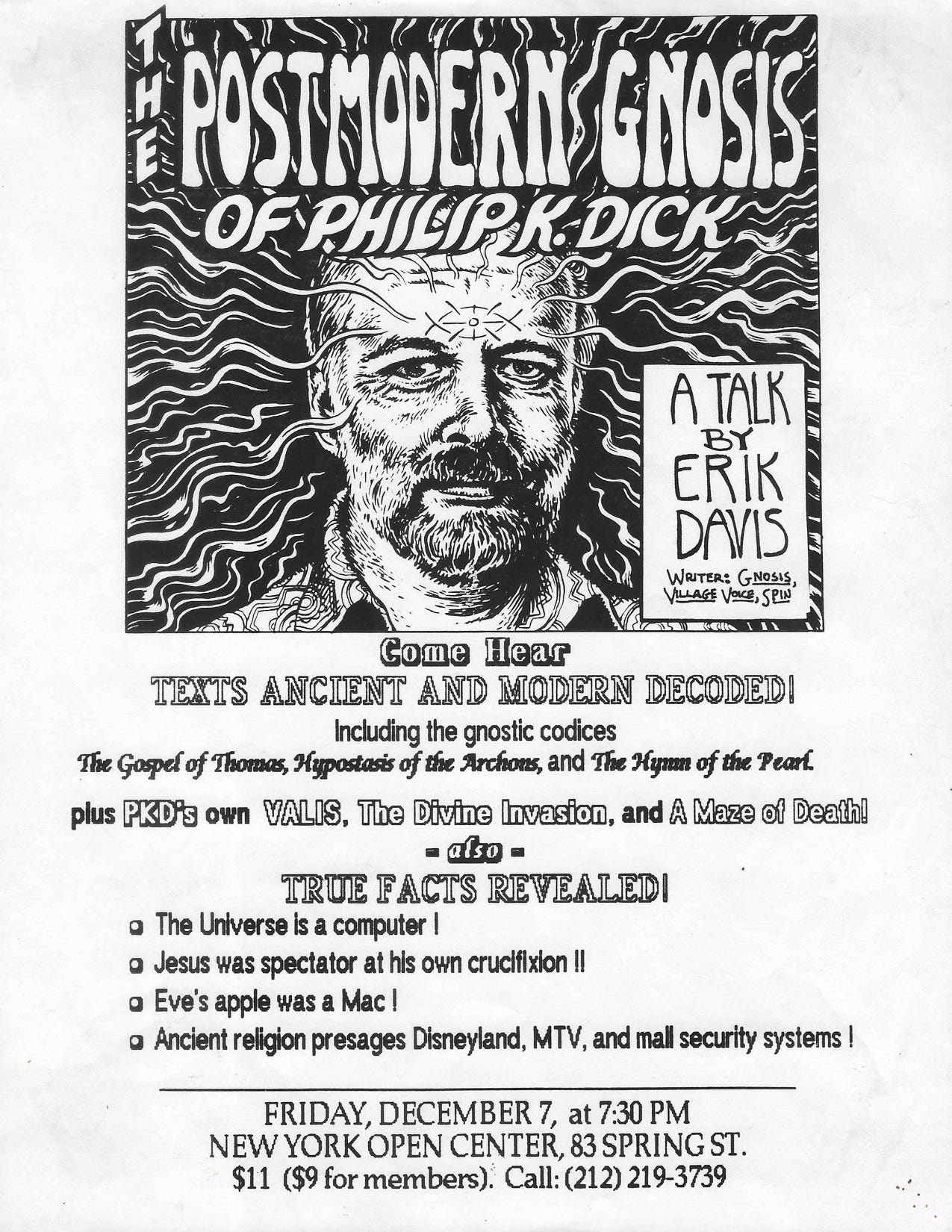

I love practices, movement traditions, and meditation methods. But one of my core hopes for the Alembic is that it also becomes a place for feral education and creative discourse. Here one of my big inspirations is the New York Open Center, an urban mystery school of sorts that was an important part of my time in the city when I lived there—actually in Brooklyn—in the late 80s and early 90s. In 1990, an Open Center programmer named JP Harpignies read some of my stuff in the Village Voice and invited me to give a talk. Here is the flier I made for it:

Ah, the early 90s….As you can see, techgnosis was already in the air, or at least in the air coming out of my lungs. This talk also initiated over thirty years of public gabbing and freelance scholarship, and was appropriately graced with a big fat synchro. Just moments before I began, I realized I hadn’t prepared a basic definition of Gnosticism for the crowd. I had a flash of panic, and anxiously grabbed my paperback copy of Valis and randomly opened it up. Here is what appeared on the very first page to meet my eyes:

This is Gnosticism. In Gnosticism, man belongs with God against the world and the creator of the world (both of which are crazy, whether they realize it or not).

Boom! Good to know that the angels of information are watching over you, even if their gifts can prove infectious, instilling obsessions that, in my case, took over a quarter century to manifest in the PKD analysis in High Weirdness.

The Open Center was a great place. I took classes in tantra and Kabbalah, and met or spent more time with high weirdos like Robert Anton Wilson, Terence McKenna, and Peter Lamborn Wilson, who demonstrated what an esoteric life of the mind might look like. I also encountered all sorts of mystic oddballs through my many talks and workshops, which covered topics as varied as Neopaganism, Star Trek fandom, technoculture, and the I Ching. JP is still a friend, and now works as one of the main programmers at the great Bioneers conference, which will be held in Berkeley this year in early April. The variety and weird bravery of the Open Center programming, and the room that the place made for political, cultural, and esoteric theorizing alongside the proto-wellness lore, indelibly marked my sense of what kind of discourse can go down in a “spiritual” center.

Reading

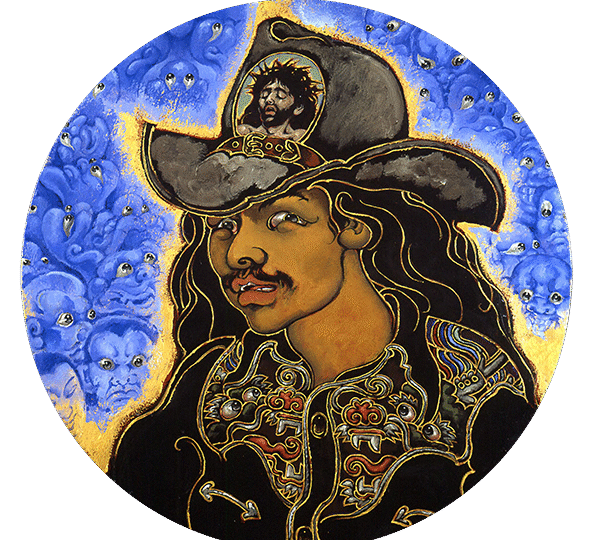

As mentioned above, my pal and fellow teach Christian Greer is a scholar of “psychedelicism,” having earned his PhD in Religious Studies under Wouter Hanegraaff in the University of Amsterdam’s Western Esotericism program. Christian’s first book, a study of psychedelic militancy in 1980s America called Angel-Headed Hipsters, should be out later this year from Oxford University Press. Full of original research and deep zine digging, the book looks under all sorts of subcultural rocks—Bob Black, Hakim Bey, the Church of the SubGenius. But it’s Christian’s other book, which was self-published last year, that I want to delight you with news of here.

Turns out that Greer and his partner Michelle Oing, who currently teaches medievalism and puppet studies at Stanford, are total pilgrimage junkies. They have spent countless hours traipsing along the webwork of sacred trails that makes up Europe’s legendary Camino de Santiago, and they have even co-founded a fraternal society — the Order of St. George’s Horse — to propagate the salty mysteries of the dharma bum. But Greer’s book, written with Oing, is about another pilgrimage route: the Kumano Kodo, a network of ancient trails peppered with shrines nestled in the largest peninsula in Japan. In 2004, UNESCO declared Kumano a world heritage site (ka-ching!) but Kumano Kodo: Pilgrimage to Powerspots walks a different path, unearthing supernatural critters, sober histories, and untagged experiences in the margins of the official story. In a brilliant demonstration of the wayward powers still to be summoned in travel writing, Greer and Oing’s rants, reports, and japes reveal the Kumano zone as a “living mandala of weird experiences,” one perfectly suited to their central pilgrim practice: the “widening of perception through risky experiments with irrational beliefs.”

Insisting on (but also complicating) the classic distinction between tourists and travelers — in this case pilgrims — Kumano Kodo is not at all a guidebook. The authors will name the drinks they guzzled — Pocari Sweat, Aquarius, and lots of Kodo beer — but there is little data about trail routes, and no names of hostels or restaurants (with the exception of one inn, J-Hoppers Kumano Yunomine, that was too amazing not to pass on to the world). As the authors point out, the armature of data that encase most travelers like an anime mecha blocks the forces most likely to unleash spiritual spunk — forces like serendipity, intuition, and play, as long as you remember that “play is an ambivalent quality, both fun and fear, failure and experiment.” The challenges the duo face are also magnified by the fact that they began their travels during the onset of the pandemic, which adds an urgent twist to their already potent, propulsive, and funny account. What did you do at the beginning of the End?

Kumano Kodo is one of the most magical books I have read in a while. Unlike many self-published volumes, it is edited and laid out well, and decorated throughout with Greer’s wonderful collages, apocalyptic mandalas that juxtapose religious iconography, Marvel comics, manga, and Western occult imagery in layers at once goofy and recondite. Part of the book’s magic is the homework the authors have done, particularly on Japan’s insanely rich folkloric bestiary, whose tengu, akaname, yūrei, and kodama nip at their ontological heels throughout. But even more magical are the gritty dialectics at play, as the critical and scholarly chops they employ paradoxically shatter the pop gloss of tourist eco-mysticism, stirring up the material muck where the spirits actually lurk. Their supernatural encounters occur in the interstices of very material realities — dreams and conversations, of course, but also sore feet, foul moods, snack machines, and the desperate need to shit.

To be sure, dodging artiface and discovering hidden byways of “authenticity” is itself the oldest line in the tourist book; the Lonely Planet is a crowded empire of managed experiences. This is where the practice of pilgrimage that Greer and Oing call for may still hold some real power. To go on pilgrimage is an existential decision, a soulshift that opens up possibilities in the world as well. Both before and during the journey, the pilgrim pledges to nourish mind, body, and the faculty of imagination. As Greer and Oing show, pilgrims also must take responsibility — for their own kicks, for their often vexed relationship to foreign places, and for their own openness to encounter, whether interpersonal or intergalactic, fun or strange or frightening.

But pilgrimage is also a social framework. One reason I have always loved visiting religious sites is that one’s fellow tourists become magical actors in the spiritual tableau. I will never forget that busload of Bulgarian babushkas at Meteora, or those vortex hunters in Sedona, or that naked Jain striding up Vindhyagiri Hill at Shravanabelagola. When my wife and I visited the Buddha’s Eight Holy Places for our honeymoon, even the profane pack of well-heeled Thais that seemingly followed us around the circuit took on a utopian spark. When Greer and Oing similarly find themselves alienated from some Kodo walkers, with their microfiber sportswear and endless Instagram posing, a spirit warns them to “Extinguish thoughts of authenticity.” It reminds them that “the people on the road are your true brothers and sisters,” and that authenticity on the road is not some untouched byway, but a stance of the heart. “Authenticity is generosity.”

What is the measure of the greatest circuses? Is it the prowess of the performers, the rareness of the beasts, the size of the crowds (or the ticket prices)? No. The measure of the greatest circuses is that you want to run away with them, to quit your life immediately and hit the hard magical road. Kumano Kodo is like a great circus. Its mixture of analysis, story-telling, visionary recitation, and bawdy carnality is intoxicating to be sure, but it is also seductive, even witchy. Maybe it should come with a warning: this book may convulse something in you, something that remembers that it is not too late for the rough romance of sacred travel, something that demands a stepping forth, a turn within and without.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.