Everybody had a hard year…

— John Lennon

Earlier this week, I recorded a most satisfying Rebel Wisdom Digital Campfire chat with Anderson Todd and RW’s David Fuller. We waxed hard about Get Back, the epic three-part Peter Jackson documentary assemblage of the 1969 Beatles sessions and rooftop show that you and everyone has already heard about because the Beatles still manage to be Big News. After an hour-long ramble, we opened up to Q&A and got the inevitable question, that playground typology that presents a rock version of astrology-through-affinity: who is your favorite Beatle?. (continued below…)

As we hurtle towards the end of 2021, I note that many essays I planned to write for Burning Shore remain suspended in the pregnant air of potential. So much of life is like this, every concrete event surrounded by lingering possibilities and ungerminated seeds, accumulating over time into an immense ghostly multiverse made up of all those things that did not have the good (or bad) graces to actually happen. I keep expecting Burning Shore to fall into an easy rhythm, but the beats keep changing. It must be alive!

Writing

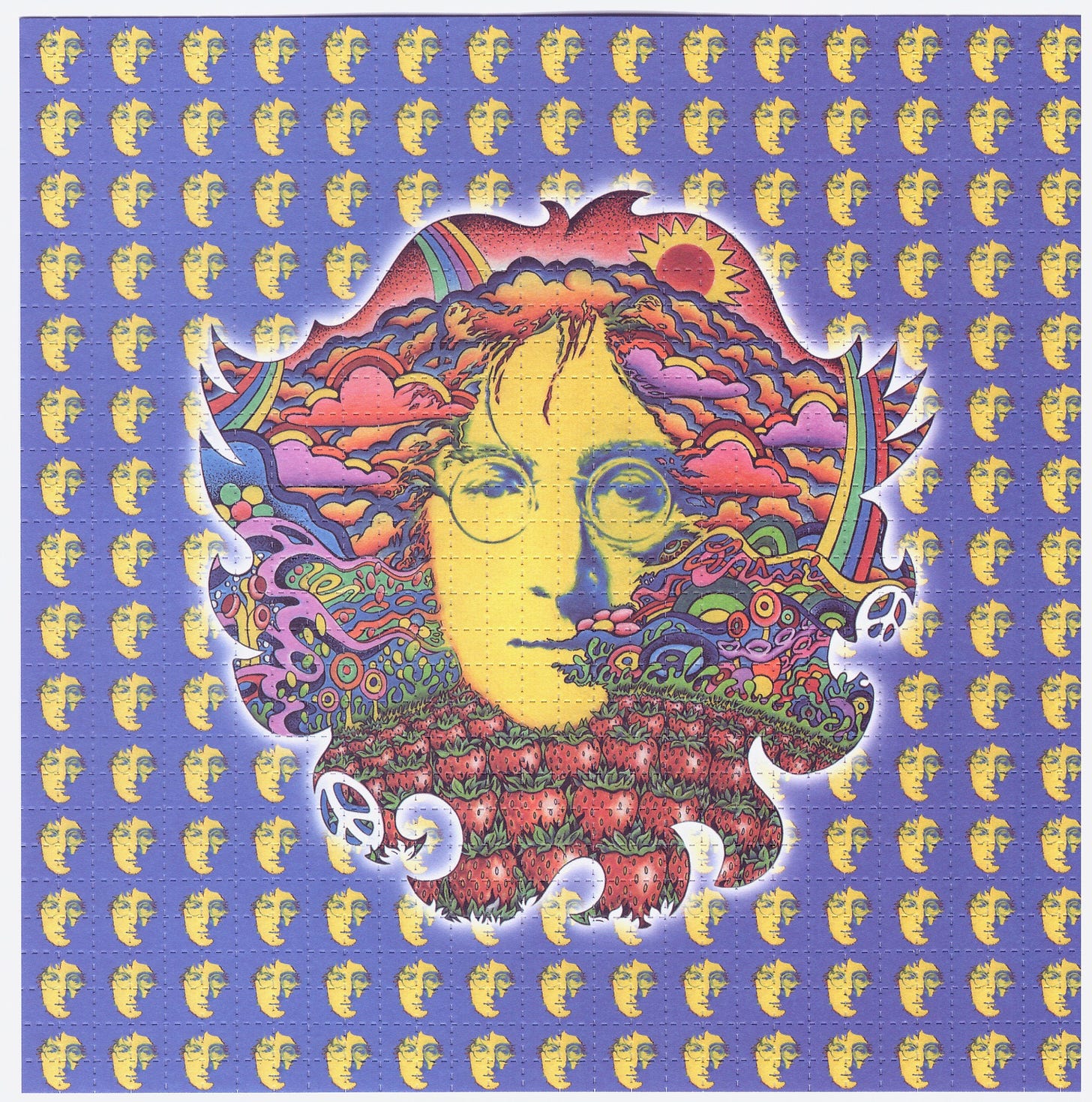

For the last year or so, I have been researching and writing a book about the Institute of Illegal Images, an LSD blotter archive gathered and maintained in San Francisco’s Mission District by the remarkable Mark McCloud. I first met Mark almost 20 years ago, during the psychedelic Middle Ages, when all of us were outlaws or marginals in one way or another. We bonded 15 years ago over a tempest in the psychedelic community teapot. That’s all ancient history now, but Mark and I became friends, and I’d swing by the III on occasion just to hang out and take in the vibes. McCloud has been collecting blotter since the 1980s and showing it since 1987. He is also a great if tricksy raconteur, a subcultural maven who’s met everyone and remembers more than most. Journos regularly write about him and his archive. Here is a shot from a recent one, which shows Mark sporting a shirt that I bought him at the Dead & Co shows I wrote about in my last post, and that features a blotter design that Mark himself first produced back in the 1990s.

Mark is generous with his stories and images, and a lot of his collection is already visible online. But a few years ago it hit me: nobody had ever collected these images in a book, nor had anyone conjured up an illustrated history of blotter, a history that would both organize McCloud’s sometimes squirrelly tales and also reflect on the stuff as a unique form of art, media, and black market commercial design—a genre that transforms radically with the rise of the vanity blotter around the year 2000. So we are doing that book, which will feature copious full-color illustrations, as well as a few dozen annotations by artists, freaks, and writers like Alex Grey, Grant Morrison, Annie Oak, and Carlo McCormick. New Year’s is my draft deadline, and the book will be published, sooner or later, by MIT Press.

Watching

Earlier this week, I recorded a most satisfying Rebel Wisdom Digital Campfire chat with Anderson Todd and RW’s David Fuller. We waxed hard about Get Back, the epic three-part Peter Jackson documentary assemblage of the 1969 Beatles sessions and rooftop show that you and everyone has already heard about because the Beatles still manage to be Big News. After an hour-long ramble, we opened up to Q&A and got the inevitable question, that playground typology that presents a rock version of astrology-through-affinity: who is your favorite Beatle?

Anderson, who like me found Jackson’s documentary in no way boring, gave an answer shockingly akin to my own: he had always been a John guy, but spent a good chunk of early adulthood as a George guy. I wasn’t surprised at the similarity here, because Anderson, who teaches at Toronto University’s Wisdom and Consciousness Lab, is cut from more-or-less the same mystic-nerd culture-vulture Gen-X cloth as I. For my answer, though, a different answer popped up out of the ether: Ringo. After weathering the fascinating, exhausting, and sometimes depressing interpersonal dynamics of the Fab Four fighting and falling apart, I could appreciate Linda’s comment in the film that you just feel good around Ringo. Plus he knows just the perfect timing required to make a fart joke come off.

The Beatles Personality Test is related to another, perhaps more significant typology: are you a Beatles person or a Rolling Stones person? Despite its arbitrary nature—what about Zappa people or Dylan people?—this particular battle of the bands not only says something about you, but also about what you think music, or at least rock music in its peak era, is for. Hear me true: I really want to answer that I am a Stones guy. I have probably listened to more of their recordings with more pleasure, at least as an adult. And let’s face it, it’s just a better look—more snarly and unsentimental and ‘70s, less compromised by the hype machine. Sure there are lots of bad Stones songs, but they made a lot more of them overall, and even the clunkers don’t deliver the sick like Paul schmaltz or that early teeny-bop twee.

But I gotta stick with the boys from Liverpool.

Part of the reason is just the nature of time and memory. Like a lot of folks, my childhood memories are woven-through with Beatles songs, the first jewels discovered in my parents’ record collection, along with Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar. Tuneful and fun-loving, the Beatles were in the mix before I was an adolescent who needed rock ‘n’ roll rebellion, though I eventually found they could kick out the jams—“Helter Skelter” is as proto-punk as any nugget on Nuggets. Now, as the rock spunk wanes into the reflective, bird’s-eye expanse of middle age, I correspondingly find they are more nuanced. The musical theatre connection is perhaps significant, since the Beatles came on rather heavy with the pantomime stuff that, while placing them farther from the live wire of rock ’n’ roll that sparks the Stones, also makes their music resonate longer and larger, through a greater arc of mimesis and musical history, a wider range of human hearts, which all comes together like that fat-ass E major chord at the close of “A Day in the Life,” resounding across the universe.

You can call this ongoing resonance nostalgia, the major complaint against our collective fascination with the Jackson doc. If you are paranoid about the culture industry, then Get Back sounds like an authoritarian command to submit to curdled retromania. But there is something timeless and even timely about this backward glance towards pop music’s magic hour, those amazing hooks and vocal blends whose fusion of harmonic sophistication and nursery melodies manage to sound like they have always been there, and which in turn makes their emergence before our very eyes and ears here especially marvelous, like watching the first amphibian crawl out of the sea. (This is particularly true with “Get Back” in the first episode, a magic coin that Paul and the boys seem to pull out of thin air, or that nowhere land where creative novelty is born.) Besides, as Anderson Todd pointed out in one of his Rebel Wisdom riffs, nostalgia is a complex emotion. It has its penetrating, contemplative sides, and its sour, lazy ones. With Get Back, I see our fascination as a healing or at least stabilizing impulse amidst the disruption of our times, an affective reflection, sometimes revelatory, on a lively and life-giving cultural commons the likes of which we will never see or hear again.

In this sense, nostalgia is just another form of mediation—another technique of circulating images and melodies and stories through the portals of time. That’s part of the paradox of the Beatles: while making fantastically novel and innovative music, they were also the most mediated thing you could imagine, saturated inside and out with signs and frames and codes. They played games with this mediation, speaking in “Beatles code” or using Dada humor as a dodge, but they also celebrated the condition. One of the many pleasures of Get Back was seeing how many old songs were almost instinctive for them, or what Heidegger would call ready-to-hand: R&B, Cole Porter, vintage rockers that gave good garage, even their own early songs, played as if they were already part of any band’s inheritance, which they already were. While such continuity with the archive can work against the sense of rupture and edge so crucial to rock performance, the mediation grows so extreme with the Beatles that it becomes something surreal, even Dionysian. In the documentary, we see them not just cycling through the tunes that helped make them what they were, but through film references, literature, even Grub St. editorials about the band’s degeneration into “weirdies,” which they read in silly voices with the kind of black humor that soldiers direct towards the corpses that can’t help but catch their eyes. The Beatles may have been the first great band who knew they were made of media.

Mediation is always in part a technical operation. With George “Mr. Jones” Martin on the decks, the Beatles became arguably the first band to transform the multi-track studio into a virtual reality, a space of controlled hallucination equal parts LSD and magnetic tape, exploiting all the loops, dubs, edits, and backwards masking that good old Nazi format affords. But it was an analog virtual reality: the simulacrum in organic, grainy, warbling guise. For the deeply digitized (in other words, us) the sort of analog media saturation the Beatles surfed seems contemporary in its loopiness but warm and fuzzy in its expression. Hence the loving attention Get Back brings to the gear: juicy shots of George’s multi-track, the fab four speakers in the mixing room, Fender amps and keyboards (Cali in the house!), all those reel-to-reels nestled in their smooth cardboard cases. And when the Leslie arrives, you can almost hear the gearheads gasping throughout the Disney+verse.

The Beatles were mages of McLuhan’s acoustic space, but they were also, to quote the Monkees, overdubs who had no choice. That’s another reason that Get Back resonates so hard right now, when all of us both seek and have been suckered into a degree of technical mediation that, as reality TV and social media and Zoom hang-outs make clear, makes our own actions and intimate relationships simultaneously objects of public consumption and opportunities for personal fragmentation. And that’s also why the camera and the boom mics inflicted on our heroes by the smarmy director Michael Lindsay-Hogg don’t seem at all “out of place” despite being extraordinarily intrusive. This was the water they swam in. Now it is the water drowning us. Rather than demanding silence, or telling Lindsay-Hogg to shove it, the boys hide in plain sight, behind silly faces and in between the notes. May we all find a way to escape without leaving the stage.

At the same time, for all their giddy and sometimes oppressive mediation, the Get Back sessions crackle with life because the band imposed one very simple restraint on themselves, a lumpen rejoinder to the studio wizardry of the previous half decade: they were going to record these songs live, and (maybe) play them live. After running through “Get Back” or something for the seventeenth time, George Martin reminds them that they already had enough decent takes to build a hit song through edits. But that’s precisely the luxury they were rejecting, opting instead for the rich and fraught interpersonal dynamics that infuse the music by virtue of having to play together. There is something, again, for us all here.

The decision also sets up a bounteous synchronicity. With no overdubbing allowed, there was no one to play keyboards on a lot of the tunes. So when Billy Preston—an old pal from the Hamburg Preludin days—swings by to say hi, they invite him to (briefly) join the band. The joy Preston takes in this extraordinary opportunity to jam with the biggest band on the planet revitalizes the boys, and makes us all smile. It also underscores what to my mind is the most important musical thread of the late Beatles: Black America, heard in these sessions not only in the Smokey Robinson songs or the 12-bar blues they goof with, but in the transformation of Martin Luther King’s dream speech into “I Want You (She’s So Heavy).” Black American music was always important to the Beatles, as it was to all great British bands of the era, though it often got buried in their music hall schtick. Here is where the rubber meets the soul.

And don’t be fooled by those analog grooves: Get Back is absolutely a product of our times as well, and especially the deeply digital manipulations that Peter Jackson and crew unleashed on the footage that Michael Lindsay-Hogg wasted on his dumb movie. Using fancy machine learning tricks, the Jackson team were able to take the unmixed mono recordings made during the Twickenham Studios rehearsal sessions and “demix” them into individual tracks that could be reconstructed into a pretty satisfying sonic ride. (More technical detail here.) This is nostalgia excavated with the inhumanly precise instruments of an AI archivist. Another bit of metal-machine sorcery allowed the team to extract conversation from the random guitar noise that the boys—particularly George and John, the two paranoids in the bunch—created in order to talk while the cameras were rolling.

But once again, the seeming disjunction between the analog haze and the digital clean room is in part an illusion. Half a century ago, the hot spots of culture were already heavily surveilled. Lindsay-Hogg snuck a candid camera into Apple’s reception area to capture the coppers he knew were coming, and brazenly tucked a bug into a flowerpot to record John and Paul’s private conversation about George. I know my wife and I cringed at this latter intimacy, as if we and the team and the world had finally gone too far. And yet what a prize the spooks deliver. John’s comments about George’s “festering wound,” and their inability to give him a bandage, are some of the most empathic and deeply human moments of the film.

But there’s the paradox of mediation: extract enough signals from the noise, and cacophony returns because you can’t process them all. I was pretty rapt viewing this film, but when I read Rob Sheffield’s charming and true Rolling Stone piece “24 Reasons We’ll Keep Watching the Beatles’ Get Back Forever,” he described a number of moments that completely passed me by. (OK, maybe it was the Norwegian wood.) While Jackson tries to keep us abreast with subtitles, viewers inevitably get lost in the surreal layers of chatter, in-jokes, and asides, a snarl that only intensifies the band’s already exquisitely honed sense of the non sequitur, that dry weirdness capable of unnerving even a Peter Sellers.

Get Back’s conversational babble (not always synced with the video) creates an experimental effect akin to the sound mixing in Robert Altman’s Nashville or recordings of the Merry Pranksters. Rather than clear communication between individuals, we get a sonic patchwork of interpersonal tensions and the centrifugal forces always working, for good and ill, against cohesion. Not to bring up Stones again (although Lennon does it throughout the film) but Get Back winds up being more avant-garde than the film Jean-Luc Godard shot of the Stones rehearsing “Sympathy for the Devil” a year earlier. Godard pans slowly back and forth through a spacious studio filled with very cool dudes; Lindsay-Hogg and Jackson give us a hot mess. Though Godard’s political insertions put the Stones in a welcome context, in a way Get Back is not only more avant-garde, it’s more social, at least in the tribal, takes-a-village, Family Dog sense. As Sheffield points out, Get Back not only weaves the wives, girlfriends, and kids lovingly into the scene, but respects them as well. It’s hard to imagine Mick and Keef extending similar invitations to their banquet. The only similarity is all the ciggies.

While the playful wrangling on display in Get Back rescues us from the grim portrait of gloom and strife that Lindsay-Hogg painted in his Let It Be film, the center clearly cannot hold. Yoko comports herself well, and Paul doesn’t seem to mind, but we know that George is having none of it, and for some good reasons, which are separate from the artistic frustrations he understandably feels given the excellence of the songs he is bringing. But the problems go beyond grumpy George and the storybook tale of Yoko as the Wicked Witch of the YES. As Paul admits with shocking psychoanalytic candor, with the death of Brian Epstein a year and a half before, the Beatles no longer have a “daddy figure” to corral their egos or manage their melange of ambition, passivity, and silliness. This makes Paul a particularly sympathetic character here, as we watch him trying to steer a ship he knows he can’t command, a ship no one is prepared to go down with. This void also helps explain Lennon’s enthusiasm for Allen Klein, which unleashes all manner of future chaos. For the Beatles at least, the problem with no daddies is that it makes room for bad ones.

This was also a generational problem of sorts, perhaps one of the most difficult and sobering lessons faced by many in the counterculture, hippies, freaks, and revolutionaries alike. The extraordinary dynamics of the later ‘60s, cultural and political, would psychologically founder on the shoals of the disorienting ‘70s, a hard drift that found many folks following paths the later Beatles helped blaze: into the arms of gurus, therapy cults, or the drugs that swallow you whole. (Again, Ringo may have proved the wisest. Asked if he liked India, the drummer, who missed his baked beans, replied, “Not really.”) For a ‘70s-ologist like me, it is of divinatory significance that, on the eve of a decade that the Stones ruled, the Beatles would break up. They couldn’t make the grade. Let it Be was released in the early part of 1970, post break-up, a year that concluded with the two great post-Beatles records, Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band, both of which set down a template for the weird years dead ahead, the coming war of blind faith and nihilism, my sweet Lord and God as a concept by which we measure our pain. These days, I listen to All Things Must Pass more, because I need that spiritual food. But at heart I am a John guy.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!