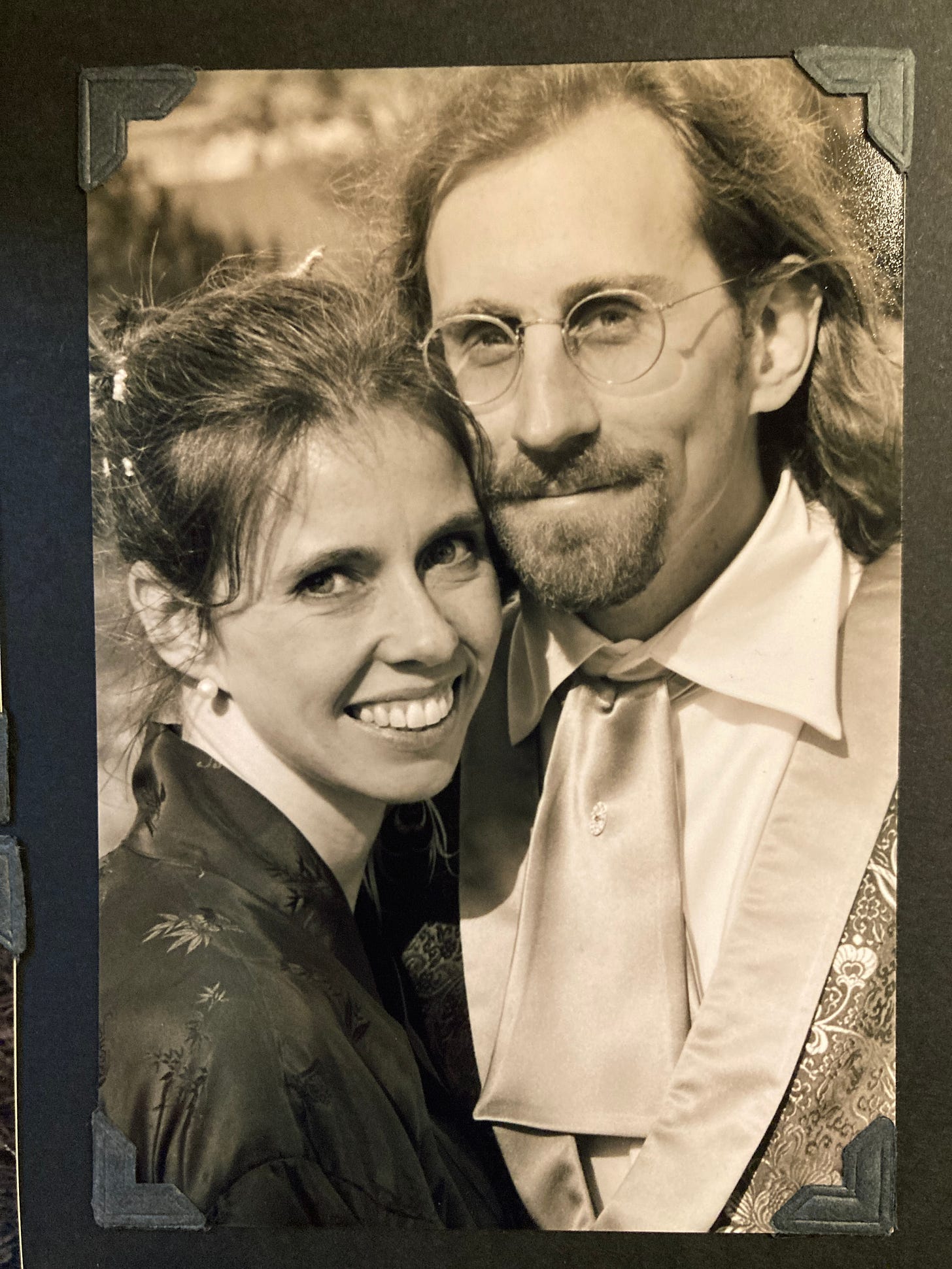

I have never been particularly drawn to write about romance, sex, or my marriage. In this way I am old school; if privacy is impossible in our era, there are still things about which we should remain discrete. It’s not a moral thing. Instead, it reflects the esoteric will to “be silent,” a gentility that safeguards the transformative and nurturing power of the personal against the Klieg lights of the 21st century over-share. But this is the year of my twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, so it feels like an apt time to raise a flute of bubbly prose. Ching.

This disappearing year also happens to be the twenty-fifth anniversary of 69 Love Songs, that fabulous and obsessive masterwork by the Magnetic Fields, a band that, more than almost any other, is woven into the substance of what I like to think of as the Jennifer Dumpert Experience. I met Jennifer in the early summer of 1992, when mutual friends, including the punk rock photographer Pat Blashill, introduced us at her place as a way to lure the already hermitish me into hanging out more. Right off the bat I loved her gregarious chat, her taste in religious iconography, her foxy vibes. But it was her record collection that really did me in: Crimson, Eno, Love’s Secret Domain, Metal Machine Music. Fucking Metal Machine Music! She gave me a sweet hug when we parted that night, and as I crossed the threshold of her apartment door, a voice resounded through my brain: you, my friend, are fucked.

You see, I was already living with a brilliant and beautiful woman, a woman I had already hurt kinda bad a few years before, and who I still loved, at least in that confused twentysomething way. Jennifer was in a similar situation, at least commitment-wise — in deep with a musician who was definitely cooler than I. So for many subsequent months, Jennifer and I hung out within a cone of silence, always just the two of us, usually in the afternoon. But we didn’t fool around. Didn’t even touch. We were gobsmacked with attraction, enchanted with talk, drawn to gaze entranced, but we didn’t cross that line. Of course, as acolytes of the Galahad fetish know, the moral clarity of the rule can bank the fires of yearning into something utterly intoxicating, almost hallucinogenic. “A long-forgotten fairytale / is in your eyes again,” Stephin Merritt would later sing, in a slightly different context, on the second volume of 69 Love Songs. “And I’m caught inside a dream world / where the colors are too intense.”

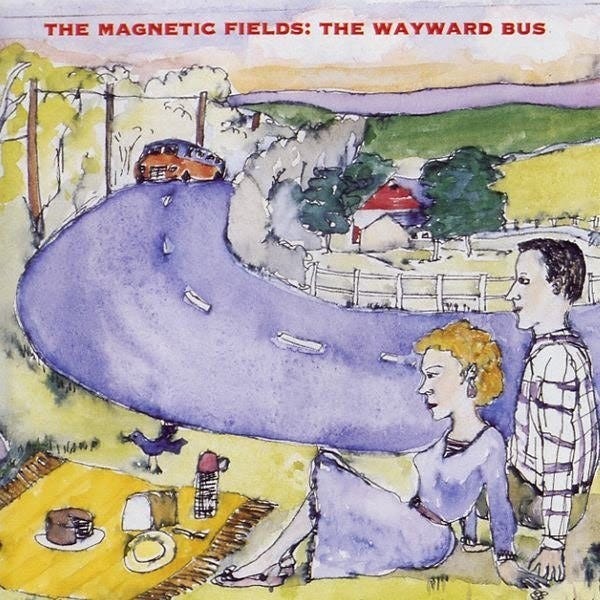

Those heady months also happened to be the period when I was listening obsessively to The Wayward Bus, the CD released by PoPuP Records that combined the first two Magnetic Fields recordings, Distant Plastic Trees and The Wayward Bus. I reviewed the album for the Village Voice that fall — front seats on the bus, so to speak — and I praised the disc’s squelchy synths and songs, which I compared to “Dada watercolor postcards from the land of the long eclipse.” I still find this collection remarkable; Merritt’s production craft and song-writing genius — and I don’t use the term lightly — is already in full effect, here in his mid-20s. Merritt himself does not sing on the tracks, which means his droll and deadpan performance persona is not part of the music.

Instead we get the elusive, almost dissociated vocals of Susan Anway — a distant cry from the warm and personable vox that Claudia Gonson would later bring to the band. Instructed by Merritt “not to emote,” Anway, who died of complications of Parkinson’s disease in 2021, expands the otherworldly weirdness of many of these songs through a kind of porcelain abstraction. At the same time, and despite the oddball sounds that appear throughout the CD, these tracks betray a knowing and deeply familiar love of pop forms (especially Phil Spector). As usual, Merritt’s sardonic sadness runs throughout the material, but the songs aren’t half as funny as they become on later albums, and the codes of gay wit he would come to make his own take a back seat to a melancholic surrealism haunted with memory, suicide, otters, tidal waves, and impossibly long white scarves. (Les Champs magnetiques, we should recall, is the name of André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s breakthrough text of automatic writing.)

I have never quite figured out how the trufans integrate these early records into the Merritt canon. I can’t really judge, because my love of them is inextricable from my own story. Even after all these years, most of these tracks remain little wayback madeleine machines, their poignant and goofy organic vibes still channeling the vexed and intoxicated moods of that time, especially tracks like “Jeremy”, “Dancing in Your Eyes,” “Old Orchard Beach,” and the indy hit “100,000 Fireflies.” On the one hand, the band gave voice to the astral romance Jennifer and I had cooked up, “touching across the room / like lovers from the moon.” On the other hand, Merritt’s old-soul pessimism gave me serious pause as I agonized over making the leap. “You’ll see the world / diving for a girl you’ll never find.”

The dam burst that winter, I dove into the torrent, and the rest is (personal) history. But the Magnetic Fields stayed a part of it. Jennifer and I hung out with Stephin after a show in 1993, and we even met his mom, who appreciated my description of her son as a “Moog-loving Proust”. We’d see Stephin and Claudia occasionally over the years, and caught performances whenever we could. We drove across the country to Charm of the Highway Strip, holiday’d with Holiday. And of course, we put 69 Love Songs on repeat for months after our wedding, which took place a week after the album debuted in September of 1999.

For many people, twenty-five years of marriage counts as some sort of accomplishment, maybe even a sign of moral fibre. I prefer to see it as gritty grace, something between madness, a glorious fluke, and a fiendish and entertaining game finely or at least obstinately played by wonderfully matched contestants. Jennifer would largely agree, though would put a characteristically rosier spin on it.

But we have no advice to give, or if we do, I like to think it’s already tucked away somewhere inside 69 Love Songs. For though it only occasionally engages the matter of marriage (and then rather cynically), the collection nonetheless scatters much wisdom amidst the wit. To wit:

The book of love is long and boring

And written very long ago(“The Book of Love”)

Everyone has had the experience of having their romantic triumphs or tragedies voiced uncannily by a dumb song popping up on the radio or an algorithmic stream. That’s because there is nothing new under the erotic sun. These songs are part of the “book of love”, which also contains music and “instructions for dancing.” Long and occasionally boring, 69 Love Songs is that book. While your own romantic life necessarily feels singular, you will probably find its episodes captured on one or more of these songs.

Love is like jazz

You make it up as you go along

and you act as

if you really knew the song(“Love is Like Jazz”)

In the early years of my relationship with Jennifer, our emotional roles were pretty well-defined: I was the angsty tortured artist, and she the nurturing pillar of happy good will. A few years after we wed, Jennifer went through an emotionally tough time, something neither of us really knew how to deal with. One day, when she was a weepy wreck, I realized the song went this way: “Come here baby, and let me hug you; I promise you everything’s gonna be alright.” Only I didn’t feel it at all; if anything, I wanted to run away screaming into the night. But I didn’t. Against all the “be true to your feelings” cant of contemporary therapy culture, I totally faked it, embracing her and patting her head as if I knew the song of loving support like the back of my hand. Over time, though, I made it mine.

That’s the paradox. While all the songs have been written long ago, you still have to improvise them, especially if you want to avoid the formulaic. This is particularly true with marriage, where so many biases, agreements, habits, and attitudes come already locked and loaded, the underlying patterns much bigger and stronger and older than you are. Free jazz is occasionally required to blow out the stops on this shit, which is partly why drug-fueled Dionysian blow-outs can be so healthy. Most of the time though, it’s best to stick to riffing on the standards, making your magic moves and surprising improvisations within the well-known patterns provided by the oldest songs in the fakebook.

You should see the things we see when we smoke

(“Queen of the Savages”)

Speaking of Dionysian blow-outs, one of the secret gifts of drugs is their capacity to weave enchantment back into long-term relationships, which, over time, become notoriously stingy about the pixie dust. I am not talking aphrodisiacs here, which is too technical and one-dimensional a concept, however useful. I mean the restoration and revivification of erotic imagination.

Nothing matters when we’re dancing

In tat or tatters you’re entrancing(“Nothing Matters when We’re Dancing”)

Another face of Dionysus. One of the most consistent themes in 69 Love Songs is dancing. Tatting up for a club groove or an outdoor gathering is a sweaty balm, for sure, and we still try and make at least one festy a year. But micro dance parties inside domestic space-time are absolutely essential. Do it now.

I’m crazy for you but not that crazy.

(“(Crazy for You But) Not That Crazy”)

This is perhaps the essential download in the album, the secret key towards love over time. Just as the difference between a drug and a poison lies in the dose, so has the secret sauce of our life together resulted from the proper mix of Romance and Realism. When you are out of young love pixie dust, Romance becomes a practice, a kind of ritual invocation that, like religion, must be passionate and crazy enough to cook up the juice but constrained enough to avoid idiocy, sloppiness, and delusion. That’s where Realism comes in. But if the Realism is not itself subject to madness, at least under the full moon, then desiccation sets in.

You and me, we don’t believe

in happy endings(“My Only Friend”)

This is the spiritual core of the Realism side of the equation: not just a boring capitulation to pragmatism, but a frank assessment of the ragged and inevitable eclipse of things. The humility and “settling” that comes with recognizing limits within a partnership is paradoxically enlivened by the knowledge that you will both die, and that, short of instantaneous mutual snuffage from a tidal wave or a wayward bus, it will end in tears for at least one of you. This is the reward for all that “work” on your relationships, all that digging into the depths: a long and lacerating grief. Do not hide from this possibility. Use it as a goad to shake up habit, and get some good carpe diem cooking.

You know the old refrain: a book of verse, a jug of wine, a loaf of bread, and thou. But how can we pull this off in the face of the unhappy endings ahead? Because…

La mort, c’est la mort

mais l’amour, c’est l’amour(“Underwear”)

French is the language of love because in French, love and death rhyme. In English, it’s more ridiculous.

69 Love Songs is mostly about young love, but Merritt has a long enough view that he can see the wayward bus bearing down on us all. But if you flip the script, that makes young love a lifelong game.

Let’s pretend we’re bunny rabbits

until we pass away(“Let’s Pretend We’re Bunny Rabbits”)

Over time, the practice of eros becomes in part a game of pretend. The play’s the thing, but it’s a magickal play that involves the invocation of animal spirits who are pretty much always ready to get down. With a little luck, and a little moonlight, you never have to stop pretending.

I’ve seen you when your ship came in

and when your train was leaving

The sweetest thing I ever saw

was you asleep and dreaming(“Asleep and Dreaming”)

Nesting is underrated. We are mammals and mammals cuddle. This isn’t just an animal fact, but a sacred one as well. The business of life, the ships and trains coming and going, the deals and transactions you inevitably make with your partner, even the sex and intimate chat, all capitulates before sleep, the other “little death” you submit to together. But when you witness your partner asleep and dreaming, and soak up that quiet intimacy, you are alone again. As in the beginning, you wonder again about their impossibly encrypted interiority, about those wonders and sometimes nightmares that insure that even here, in the dozing heart of domestic safety, the Mystery yawns wide:

We don’t know anything

You don’t know anything

I don’t know anything

About love

But we are nothing

You are nothing

I am nothing

Without love(“The Death of Ferdinand de Saussure”)

Jennifer and I have both spent a lot of time around Zen, which means we have spent a lot of time trying be nothing. Zen doesn’t talk a lot about love or compassion, which is kind of cool actually because, as Merritt notes in “Love is Like a Bottle of Gin,” love is “grossly over-advertised.” But intimacy is another story. In one of the best koans in Zen, Dizang asked Fayan, “Where are you going?” Fayan answered, “Around on pilgrimage.” (He might as well have said, “To fall in love.”) Dizang then asked, “To what purpose?” Fayan replied, “I don’t know.” Dizang then gave it up: “Not knowing is most intimate.”

If you don’t cry it isn’t love

(“If You Don’t Cry”)

Sometimes I imagine some post-mortem state where you are able to turn around and look at your life as you get sucked into the bardo, and rather than seeing ups and downs, good and bad, pain and pleasure, you just see one vast glorious tapestry, a fabulous fabric that weaves together all the threads, dangling and dyed and otherwise. From this non-dualistic perspective, love is death, intimacy is illusion, passion is a honey-covered razor blade. So what are you complaining about?

Whining and pining is wrong and so

on and so forth, of course, of course

but no you can’t have a divorce(“Busby Berkeley Dreams”)

In Living in a Material World, Martin Scorsese’s great documentary about George Harrison (the Beatle closest to my heart), Olivia Arias (the Beatle wife closest to my heart) says something brilliant about her long partnership with a very complex character: the secret to keeping your marriage together is to not get divorced. In other words, when the going gets rough, as it does for everyone, stubbornness and cussed refusal can be a worthy ally, especially in a low commitment culture like ours that celebrates loose ties and narcissistic needs. There were a few years where Jennifer and I were so messed up no one we knew wanted to hear about it anymore, but fuck if we were going to give up on the hunch that we would be sweet old farts together.

Upcoming Events

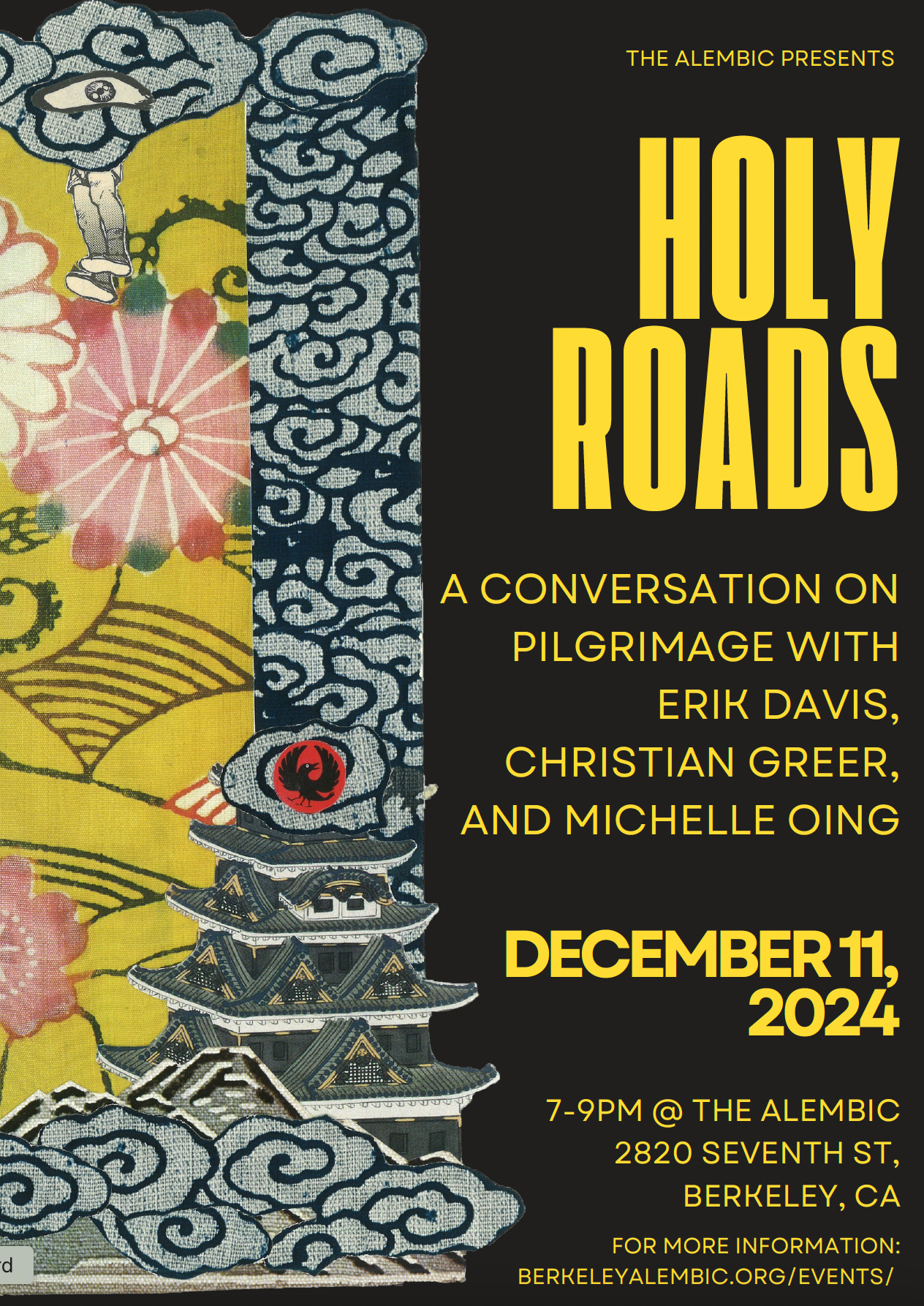

• This coming Wednesday, on December 11th at 7pm, my Chalice mate Christian Greer and his partner Michelle Oing will be presenting on what Christian argues is the ultimate hardcore cosmic practice — not psychedelics, but pilgrimage. As Burning Shore readers know, Christian and Michelle wrote a terrific account of their sacred stroll along Japan’s Kumano Kodo, and now they are working on a book about the Camino de Santiago, which they visit every year. Because Christian and Michelle are so much fun, I will be joining them onstage. It’s my last Alembic event for the year, so I hope to see you there. It’s a sliding scale donation thing, but please register beforehand.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.