Indian Film Music

Slowly gyrating across a Bombay cabaret stage, a busty courtesan promises a night of delight to an enraptured drooler; then a greasy Elvis clone in shades, bell-bottoms, and a sequined jacket hound dogs in Hindi alongside a girl in a white leather miniskirt and thigh-high boots; then strings, sitars, and ardent voices swell as a young couple flies through blue skies and frolics through door frames propped up on the side of a verdant hill, door frames painted with flames and lowers and leading nowhere.

These are a few Indian song-and-dance sequences from a VHS tape rented at Baba Foods in Brooklyn. Because they’re compiled from a bunch of Bombay films, the lusciously wacked clips are liberated from the turgid story lines that usually restrain them. They just keep coming and coming, saris, smiles, and spurting fountains, like India’s fever-dream of MTV.

But in the land of sacred cows, Milli Vanilli’s rule. For all the variety of these clips, one thing is constant: the voices we hear don’t belong to the actors we see but to Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi, two of the most popular and prolific of Bombay’s playback singers. Since the late 1940s, when the original generation of singing actors died out, playback singers have provided the pipes for the handful of de rigueur song sequences that glitz up nearly every commercial film pumped out of India’s massive movie-making machines (750 movies a year). Far more than just playing Martha Wash to the C + C Star Factory of Bombay, today’s greatest playback singers—Rafi, Mangeshkar, her sister Asha Bhosle, Mukesh—glow like Madonna and reign like Sinatra (and churn it out like Elvis; Lata’s made 25,000-plus recordings).

Schooled to believe that America is the world’s pop culture pusher, it’s hard for us to comprehend the global star power of these singers of the dominance of a film industry that mesmerizes millions not only in south Asia, but throughout the Middle East, Indonesia, Eastern Africa, and southern Russia. Given the long, formulaic, garish narratives of Hindi film, their cross-cultural appeal no doubt predominantly stems from the ebullient and eclectic sounds of filmi geet (film music)and the generally fantastic and sexy scenes they’re wedded to. These song sequences are paragons of escapist desire so fetishized and extreme that they need to draw juice from the whole of the world’s music just to sustain themselves (not just American jazz and rock, but European, Latin, and Asian sounds as well). And by restlessly pillaging exotica while simultaneously honing the art of pop product and doing it all with visual seduction in mind, filmi’s composers and playback singers create soundtracks not just for their movies, but for a planet dripping in creole media.

I first heard filmi music when I opened the door to an empty Indian restaurant on East Sixth and walked into a swirl of peppy tablas, harmonium, and sugary vocals. In five seconds flat the waiter slapped on the ragas, which he must have figured conformed more to my notion of Orientalism. By shutting down his own pop pleasure and firing up the “real” stuff, he was dutifully acknowledging the legacy not of India’s great art music, but of the myopia of ’60s rockers too stoned to realize they were turning on to classical music. I mean, by 1967, when all those free spirits at Monterey were cheering Ravi Shankar just for tuning up, filmi composers had already cranked up the sounds of Indian folk and classical idioms into the fleshy ache of a massively popular culture that had already become the true “people’s music.” And before George Harrison and Brian Jones exoticized the Beatles and the Stones with mystical drones, the Bombay masterminds were already joyously devouring Western soundsnot only the brash winds and racing strings of Hollywood, but vibes, Latin and polka beats, Mills Brothers arrangements, scat, Dixieland, and twangy surf guitars. Yesterday never knows.

Thanks to the South Asian communities that have been growing in New York since the early ’70s, today you can pick up loads of filmi music on cheap cassettes at the Indian grocery stores scattered through the boroughs. There’s some seriously cloying muck here (and the genre has declined through the ’80s, giving way to dance-pop ghazals), but at two to three bucks a shot, it’s hard not to take chances. But folks overwhelmed by The Best of Lata Vol. 9 and unimpressed with the infinitely xeroxed sound quality of the grocery tapes should hound down the three volumes of Golden Voices of the Silver Screen. A compilation of the filmi golden age (’50s through the ’70s), Golden Voices is the soundtrack to an Indian-produced British TV series that stoked the country’s many Asians and became cult viewing amongst some palefaces.

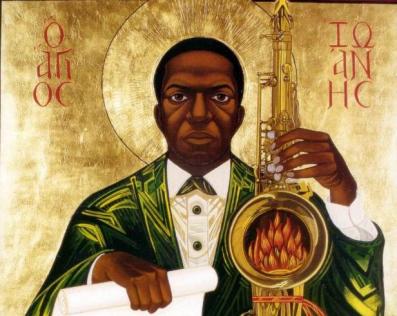

Even without the pretty pictures, the material is intoxicating. The sound effects and Carl Stalling panache of Lata’s “Tere Bina Aag Yeh Chandri” make the song as romantic and weird as its title (“Without You There Is No Fire in Moonlight”); “Jaan Pehchaan Ho” puts Dick Dale on a longboard to Bombay; and the silky glow of “Dil Cheez Kya Hai,” with its yearning violin and plaintive modal probes, sends you where all that mood doodle they play in New Age book stores only dreams of going. Most pieces are grown from the motherland’s own rich soil, and forms as diverse as qawwali and the ghazal are expanded upon, but those looking for a folk core of authenticity here will find themselves lost in a hall of mirrors. Because the vocal melodies are often modes based on classical rags or local songs that have been adapted for Western scales and orchestras, filmi tunes can be delirious rides between the familiar and the strange, as a single song will tease its way from girl-group bubblegum to folky melancholy to nursery rhymes to modal sitar evocations of lands replete with the world’s only D-cup goddesses. I mean, how do you assimilate a song like “Tere Bina Aag Yeh Chandni,” which cribs Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherezade”, itself a gaudy Orientalist workout in the first place? Start untangling this stuff and soon you’ll be hearing the snake-charming horn blast that opens the 1963 cut “Daiya Re Daiya” as a response to Coltrane’s “India.” The shit’s disorienting.

Though the watershed works of composers S.D. Burman and Naushad get the most ink in the literature, my fave would have to be S.D.’s son, Rahul Dev Burman, in part because his exuberant eclecticism and mind-fuck juxtapositions are coming out of the same thrill of clashing forms that drives my own pleasure. He also brings the guitars way up front. On the third volume of Golden Voices, his “Aaj Ki Raat” features a moody, ominous guitar line, a hard r&b brass break, and a weird flute that feedbacks like it wants to be reincarnated as Thurston Moore’s guitar pickup. Burman’s very popular soundtrack to Hare Rama Hare Krishna—easy enough to pick up—has Calypso melodies, scat singing, and eerie psychedelic drive. Proto-sampling? You bet: not only do these bits of Westernalia often function as discrete chunks and textures with the quotation marks intact, but one of the rituals of film-goers is to guess just what’s being bit. R. D. Burman’s cut-up aesthetic achieves total sublimity on “Piya Tu Ab To Aaja” from Asha Bhosle Hits All the Way, a hallucinatory jump-start bricolage that fuses in five minutes the ideas that John Zorn has been fucking with for years. It’ll pry open your third eye to visions of James Bond shooting at Ennio Morricone in Mexico while table players tickle go-go dancers on Persian carpets.

Given India’s limited recording technology and filmi music’s tendency toward triple-chocolate fudge arrangements, much of the Golden Age material achieves a delirious cacophony, though the sinewy and remarkably funky beats of the tabla and dholak pull you along even as you’re drowning in soupy strings. And while girlish squeals of the female playback singers are an acquired taste, it’s their melodic passion that ultimately puts this strange brew over the top. Even without understanding the lyrics, you can feel them mourning, loving, or playing hard-to-get. Neither “universal” nor “exotic,” the unabashed melodrama of Lata, Asha, and Geeta Dutt invigorates the thousands of miles of cultural difference that lie between Bombay and my living room the way that eyes flirting across a room break down distance while maintaining it at the same time. When Asha Bhosle slides up to a note, she seduces the ear the way a sitar does. When she starts in with the hiccups, coos, and raspy breaths, she just seduces.

As Kobita Sarkar write in his Indian Cinema Today, Bombay has produced “a cinema excelling in titillation.” Because onscreen kissing wasn’t permitted until the ’80s, the romantic song-and-dance sequences carry a heavy imaginative load, representing the “wish fulfillment of both the audience and the characters in the film.” Edge in India’s version of the Madonna/whore complex, the coquetry of the female voices, and a cultural bias toward the voluptuous, and you have a media of gaudy eroticism made all the more appealing for its ultimate restraint. What Sarkar sees as a “sickening fetishism” can also be seen as a fantastic fusion of music and image into fully realized modes of desire that are set aside from the normal shit-stream of life and its low-budget narratives. These sequences often have nothing to do with the plot and take place hundreds of miles from the main setting. Video compilations of these clips—organized around the film star, the year, the playback singer, and occasionally the composer—also attest to the degree to which these sequences stand outside the story lines. What started out as Third World derivations of American movie musicals became visionary, unpretentious precursors of MTV’s liberated flux of tune and titillation. But unlike MTV, the fantastic hunger of these images spreads into the sounds themselves. Playback singers and filmi composers sample the globe and pour the sugar thick, and their music teases out an essential pop urge: We want the world and we want it now.